-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2025; 13(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20251301.01

Received: Feb. 2, 2025; Accepted: Feb. 23, 2025; Published: Feb. 28, 2025

A Study on Supply Chain Resilience and Its Impact on Supply Chain Performance in the Coffee Industry of Rwanda

Honorine U.

Chongqing University of Post and Telecommunication, Chongqing, China

Correspondence to: Honorine U., Chongqing University of Post and Telecommunication, Chongqing, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study aims to explore how supply chain resilience (SCR) affects supply chain performance (SC P) within the Rwandan coffee sector, alongside supply chain agility and flexibility as mediator variables. Data were collected via self-administered questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with 316 respondents across the Rwandan population working for coffee industries, Key The findings of this research validate supply chain resilience's (SCR’s) positive influence on supply chain performance (SCP) while showing agility together with flexibility as intermediate factors that enhance SCP and SC. Industrial firms operating in Rwanda’s coffee sector need to enhance their capacity to resist risk since climate-related events and worldwide supply chain instability happen more often.

Keywords: Supply chain resilience, Supply chain performance, Coffee industry, Rwanda

Cite this paper: Honorine U., A Study on Supply Chain Resilience and Its Impact on Supply Chain Performance in the Coffee Industry of Rwanda, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20251301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Businesses need to build supply chain resilience, which is mostly driven by supply chain disruption caused by various factors, including technological innovation, globalized supply chains, and expanded outsourcing [1]. In supply chain literature, resilience is an organization's ability to bounce back from setbacks by reacting quickly to unforeseen circumstances [2]. It has been found that it is critical for business sectors such as coffee production to portray resilience owing to the vulnerability of supply networks to various market and environmental considerations. One of the greatest challenges that it has to face is its dependence on coffee delivered from developing countries [3]. It is from developing countries, and it is still sensitive to influences such as fluctuating costs or detrimental climate changes that affect the growth of coffee beans [4] Elements constituting supply chain performance (SCP) are basic factors such as effectiveness, responsiveness, and customer satisfaction in a given supply chain [5]. However, resilience alone is insufficient without complementary capabilities such as flexibility and agility, which mediate its effects on performance. Environmental factors, particularly climate variability, further influence the relationship Between resilience and performance, acting as moderating variables. For firms to achieve effective supply chain resilience, some strategies are suggested, like supply chain flexibility and agility. Flexibility, in this regard, assumes that firms should be able to cope with changes and uncertainty in business environments, such as changes in customers’ requirements [2], [6]. However, there are several gaps in the literature that the following work seeks to address more expressly. The literature that the following work seeks to address more expressly. Despite the increasing interest in supply chain resilience, some gaps still exist, which this study seeks to address.

1.1. Research Gap

- 1. Prior research has identified the overall connection between resilience and performance. Still, more research is needed to identify agility, flexibility, and performance. Still, more research is needed to identify agility and flexibility as mediators of resilience and performance within and specifically in the coffee Industry [7], [8].2. Most studies on SCR have focused on developing economies neglect the unique challenges faced by developing regions where coffee production is a critical driver of economic growth [9].3. The coffee industry faces distinct risks, such as climate change and dependency on smallholder farmers, which necessitate a deeper understanding of how resilience can be developed and applied as a supply chain enabler [9]. To fill such literature gaps, this study explores the moderating influence of supply chain agility and flexibility with the effects of supply chain resilience on supply chain performance in the coffee industry of Rwanda. By exploring these relationships, this research makes the following scholarly contributions. First, it contributes practical insight into the functions of agility and flexibility to extend theories on supply chain resilience. Second, it provides a discursive focus on the emerging framework of challenges and opportunities for building resilience in the coffee supply chains, and it presents recommendations to the supply chain players and policymakers concerning how to foster better performance in a sector that is both highly sensitive to shocks and crucial to the economy.

1.2. Research Objectives

- With the general objective of the current study, which is to analyze the impact of supply chain resilience on supply chain performance in the Rwandan coffee industry, the following three specific objectives were considered by the researcher:(1) To analyze the impact of supply chain resilience on supply chain performance.(2) To analyze the mediating role of supply chain flexibility in the relationship between supply chain resilience and supply chain performance.(3) To analyze the mediating effects of supply chain agility in the relationship between supply chain resilience and supply chain performance.

1.3. Profile of Rwanda Coffee Industry

- Rwanda’s coffee sector is vital, contributing to 24% of the agricultural earnings and benefiting over 400,000 smallholder farmers. Coffee cultivation started at the beginning of the twentieth century and has since grown into a renowned Rwandan agricultural venture. Cooperatives have particular dominance in coffee production, as these affect the sponsorship of small-holding farmers equitably in terms of profit sharing. Industrialized coffee production utilizes these benefits from high-altitude farming, volcanic soils, and climate conducive to the arabica crop, which is renowned for its high quality around the globe. [10] These cooperatives have brightened the lives of thousands of farmers, hence enhancing community development. Other new developments, including coffee tourism, have continued to diversify Rwanda's revenue base and solidify the country’s brand as the premier coffee producer in the world. [11] However, the coffee sector itself is not without problems, including climate change, price volatility in the world markets, and the continuing threats posed by pests and diseases. It’s such risks That has led to the use of sustainable farming practices such as production that are resilient to disruptions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supply Chain Resilience

- Supply chain resilience has gained significant attention as disruptions continue to occur globally. As the capacity of that supply chain to mitigate disruptions, recover, and learn from them, resilience underpins the sustainment of business. Therefore, in the context of agriculture and especially the coffee sector, it is crucial to understand how internal capabilities shape resilience to external risks. Literature shows that supply chain resilience refers to “the capability of the supply chain to respond quickly to unexpected events to restore operations to the previous performance level or even to a new and better one.” Their framework of supply chain resilience. [12], highlight that capabilities (such as efficiency, adaptability, and recovery) have a positive effect on resilience, while vulnerability factors (pressure from outside and resource constraints) harm resilience; the outcome is two extreme conditions of high vulnerability and high capability or low vulnerability and high capability, and one moderate condition commonly referred as ‘Match. ‘That is why resilience is considered a specific set of intellectual and manageable assets that define the capacity of organizations to respond to disruptions. These include flexibility, agility, and collaboration assets. [13] However, resilience in the context of the agricultural sector and even in developing countries has received relatively little attention. Literature on SCRM across agriculture industries reaffirms these industries’ preconditions concerning natural resources and exposure to climate conditions as risky factors. [14]. As this study noted, there is a dearth of literature that focuses on understanding the relationship between the supply chain's internal capabilities that have been identified and the external environmental risks. Additionally, little research attention has been paid to the coffee industry in developing countries, especially to supply chain vulnerability to climate fluctuation. However, the literature has also proposed various measurements of SCR, such as agility, collaboration, information sharing, trust, visibility, and risk management culture [7]. To understand the interaction between each measure and their relationship to performance, studies must first consider the variables that compose each measure. While each of these factors represents an important component of SCR, there are also quite a few overlapping areas between them. The framework of this study follows the report by [15] and [16] who indicate that the SCR of a company can be measured by its agility and flexibility.

2.2. Supply Chain Flexibility

- Flexibility in the supply chain refers to a firm's ability to adjust to changes in the business environment and stakeholders’ requirements while consuming the least time and dedicating the minimum effort [2]. The benefits of flexibility for supply chains include enabling firms to adapt to unexpected changes, allowing firms to show effective responses to supply chain disruptions, and facilitating firms’ abilities to cope with supply chain uncertainty [6]. Operationally, supply chain flexibility refers to a firm’s ability to modify suppliers’ orders, delivery times and schedules, and production capacity to mitigate supply chain disruptions [16]. Scholars like [17] and [18] asserted that flexibility is essential for creating resilience.

2.3. Supply Chain Agility

- An agile supply chain can show quick responses to sudden changes in demand and supply [2]. It has been described as a firm’s ability to modify its operations to changes in the business environment [19]. In the context of supply chain resilience, supply chain agility refers to the quick satisfaction of customers based on a quick response to short-term changes [20]. Supply chain literature mainly examines three distinct areas, which include supply chain responsiveness and speed alongside the detection of changes. [21]. Agility and flexibility stand apart as specific response skills for the supply chain despite their close relationship, as identified by [22]. Notably, being agile strengthens several supply chain competencies, which include distinctiveness and capability to endure ambiguity along with learning abilities, information exchange and market knowledge acquisition, problem-solving capabilities, and decision-making intelligence [23]. Competitive firms need agility to perform well in markets that experience changing conditions such as supply chain disruptions, quick recovery, business recovery protocols, and supply chain recovery demands [24] and [25]. Agility and resilience complement each other, wherein agility denotes how quickly an organization can adjust, transform, and react to evolving circumstances, while resilience is about an organization’s ability to recover and bounce back from adverse events or disruptions. Both are crucial in today’s unpredictable business landscape. [26]. Therefore, two essential components that compose our research model are agility and resilience.

2.4. Supply Chain Performance

- Supply chain performance includes three main approaches process-based approaches (i.e., integrated processes from suppliers to end customers), perspective-based approaches (i.e., supply chain operations reference model and balanced scorecard models), and hierarchal-based approaches (strategic, tactical, and operational level) [27]. Embrace customer satisfaction, improving process transparency, decreasing supply chain process errors, removing job redundancies, and reducing administrative expenses are a few examples of supply chain performance measurements from earlier studies [28]. Supply chain performance can be described as the ability of a supply chain to deliver products or services and the efficiency, which can be measured by several KPIs. Some of the key measures include cost, the total supply chain cost efficiency, delivery time, which is an assessment of the delivery performances, the quality aspect containing the incident of product defects, and the flexibility and agility tests on the responsiveness of the supply chain. Further, sustainability is gradually considered an essential criterion when evaluating the effects of supply chain operations on the environment. The latest literature on performance metrics focuses on sophisticated metrics, particularly in the context of Industry where, through digitalization, the visibility and responses have improved, and hence, Metrics can be effectively made to cover the readiness, response, and recovery aspects of resilience. Through analyzing these indicators, one can derive measures useful in enhancing the overall supply chain function with competitiveness and customer satisfaction as ultimate goals due to fluctuating market conditions.

3. Hypotheses Development and Conceptual Framework

3.1. Supply Chain Resilience and SCP

- Resilience practices and supply chain performance are closely related, and there is a chance that they will have reciprocal good or negative consequences [29]. Previous studies have offered data to expand our grasp of the relationships between SCR and SCP by deconstructing resolution alternatives and undertaking comprehensive studies [30], [31]. As a result, resilience is essential to SCP since it helps attain and maintain appropriate performance [32], [31]. Levels over time while serving as a deterrent to disruptive events [32], [30]. Furthermore, past research has shown that SCP and organizational success are positively correlated. Consequently, SCR and SCP can be seen as essential connections, a crucial linkage, aiding in formulating a strategic path [23]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:H1: Supply chain resilience has a positive impact on supply chain performance.

3.2. Supply Chain Agility and SCR

- An agile supply chain can show quick responses to sudden changes in demand and supply [2]. It has been described as a firm’s ability to modify its operations to changes in the business environment. [19]. In the context of supply chain resilience, supply chain agility refers to the quick satisfaction of customers based on a quick response to short-term changes [20]. According to [14] Different disruptions, for example, changes in customers ‘demand and other environmental factors, for instance, climate change, which affects coffee farming in Rwanda, are important when considering agility for the supply chain. As noted by [14], it is important to note that an agile supply chain should demonstrate the ability to respond to changes in demand as well as other factors, such as environmental disruption like climate change, which affects the supply chain. For instance, in the case where a particular area has a dry season, a flexible supply chain can easily change its sources, work on differential timing, or try to make changes to stop having greatly low performances due to the drought. Based on this reasoning, [34] Suggests that agility improves performance since it allows firms to avoid slippages and reduce response times to disruptions in a way that ensures that service standards are met and customer satisfaction is maintained. According to [5], Business agility can only neutralize the impacts of resilience on performance. An effective supply chain in a volatile environment, including coffee production, would take little time to develop a phase that would help it bounce back in the case of a disruption, thereby achieving high performance. Drawing on the aforementioned arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:H2a: Supply chain agility mediates the relationship between supply chain resilience and supply chain performance in the coffee industry of Rwanda.

3.3. Supply Chain Flexibility and SCR

- Testing the influence of supply chain capabilities (i.e., flexibility, velocity, visibility, and collaboration) on supply chain resilience [16] indicates that all these capabilities have significant influences on supply chain resilience. Examining supply chain resilience using three key forms of resilience, i.e., engineering, ecological, and evolutionary resilience [35], indicated that all these three forms are essential for a supply chain to recover after a disruption, or, in other words, resilience. According to the authors, ecological resilience is a function of adaptive capabilities such as flexibility, adaptive capacity, and function redundancy. On the other hand, generally, supply chain flexibility is a critical dimension to ensure supply chain resilience, which leads to good supply chain performance. [36], [37]. The literature has conflicting opinions about how these skills affect other concepts like supply chain performance. Supply chain flexibility has been found to have a considerable impact on supply chain performance in certain research. [37], [38] found that the impacts of supply chain flexibility on performance were negligible. Based on this research, it was anticipated that supply chain flexibility would play a mediating role in supply chain performance and resilience. Hence, the following hypothesis was suggested:H2b: Supply chain flexibility mediates the relationship between supply chain resilience and supply chain performance in Rwanda's coffee industry.

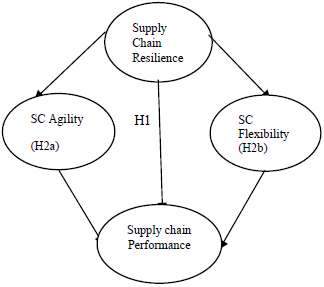

3.4. Conceptual Framework

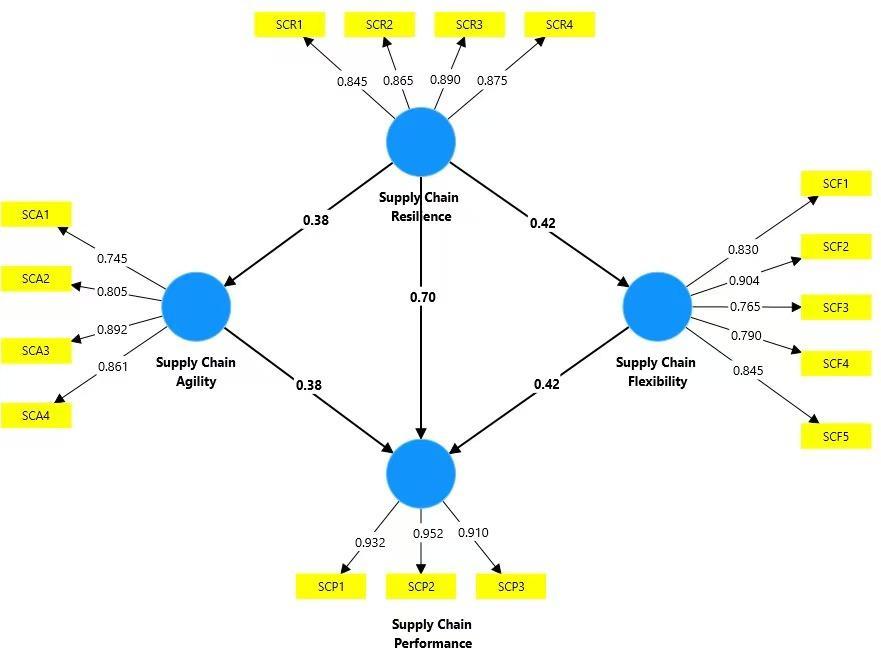

- The conceptual framework that leads to the overall processes of this study has been drawn based on the research objectives, and it consists of four variables, including independent (supply chain resilience), dependent (supply chain performance), and mediating variables (Agility and Flexibility).

| Figure 1. Conceptual framework |

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

- The researchers selected their participants through purposive sampling because they had a deep understanding of Rwanda's coffee industry supply chain. The selection process for both questionnaire respondents and semi-structured interview participants focused on individuals who had extensive experience in supply chain activities along with active involvement. This methodology ensured participants could supply meaningful data. This research design utilized both quantitative questionnaire data and qualitative interview analysis to produce a full comprehension of the study's issues. This research designed its methodology as descriptive to analyze supply chain variables concerning resilience within Rwandan coffee chain structures. Through this research design, scientists gathered both numerical data and personal descriptions to conduct a detailed study of patterns between variables across diverse participants.

4.2. Data Collection Methods

- To collect quantitative data, a structured questionnaire was developed and distributed among employees across various companies in the coffee industry. A colleague working in the same sector facilitated the dissemination of the questionnaires, which were shared among employees and extended to other companies through Google Forms. A total of 250 responses were collected, providing a robust data set to analyze trends and patterns in supply chain resilience and performance. The questionnaires included sections to capture demographic information, participant’s experiences with supply chain disruptions, and their perceptions of factors such as flexibility, collaboration, agility, supply chain resilience, and supply chain performance climate variability, which are the central focus of this study.For qualitative insights, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a sample of 66 individuals. These interviews were conducted over phone calls, recorded with the participant's consent, and subsequently analyzed. The semi-structured format allowed flexibility to explore respondents’ in-depth perspectives on specific topics.

4.3. Questionnaire Design and Testing

- The questionnaire scales used in this research were based on previous studies. [14], [39], [9], [40], [41] [42], [14]. In this study, five-point Likert scales and semi-structured interviews were used for rating. Likert scales were first developed in 1932 as the popular two-directional, five-point response, and it is impossible to incorrectly build a Likert scale [43], [44] discusses the advantages of semi-structured interviews in allowing researchers to probe deeper into participants while following a structured guide. To measure supply chain flexibility, I used five items adapted from [45], [46] and [47]. Who questioned the extent to which the firm was able to change the structure quickly, cost-effectively, and without negatively impacting the quality of services in response to changing business conditions? Furthermore, they questioned the extent to which their firm was able to change delivery schedules to meet customer requirements and were more flexible to changes than competitors.To measure supply chain agility, I used four items adopted from [48], [49], Respondents were asked to what extent a firm could quickly detect changes in the environment, continuously get information from suppliers and customers, and are characterized by a speed in adjusting delivery capability, improving customer service, and improving responsiveness.To measure supply chain resilience, four items were adopted. [16], [50], [51] [52]; Respondents were asked to what extent a firm could promptly restore its initial condition following any form of disruption, a firm could maintain a specified level of interconnectivity among Its constituents, and a firm could determine the frequency of risk assessment.Finally, to measure supply chain performance, three items were adopted [53], [54], [55], [47] They questioned respondents about the extent to which their supply could deliver zero product, minimize total product cost, respond to and solve problems, meet the expected quality of our supply chain partner, and to what extent the firm has satisfactory sales growth. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree “to “Strongly agree.” In addition to the model’s main constructs, we included three relevant control variables on supply chain performance, namely the company size (in terms of number of employees), the number of work experience, and the type of supply actor.

4.4. Ethical Consideration

- In this research, following all ethical guidelines was necessary to make integrity and ethical sense of the entire research. In the process, respondents were informed clearly that the information provided would be used strictly for academic purposes and obtained consent before participation. The explanation given to them also contained the concept of supply chain expertise to ensure a proper understanding of the context of the study. This contributed towards transparency, respect, and trust in the research process in line with better practices of ethics.

4.5. Data Analysis

- The responses from the questionnaires were analyzed using SPSS version 27, which was used for data cleaning, where missing values were checked and treated, followed by descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics. Reliability analysis was conducted to ensure the consistency of measurement scales, which resulted in a Cronbach's alpha above the acceptable threshold of 0.7. Subsequently, PLS-SEM was employed using Smart PLS 4 to examine the complex relationships among the variables defined in the theoretical model. The model included four latent variables with specific indicators. The analysis focused on path coefficients to determine significant relationships, employing criteria such as R2 values, composite reliability, and validity tests for comprehensive results. The findings from SPSS provided a foundational understanding of the data, while the PLS-SEM analysis offered deeper insights into the hypothesized relationships. The qualitative data from the semi-structured interviews were transcribed and thematically analyzed to identify recurring themes. This provided an in-depth understanding of the strategies and practices employed in the coffee industry to enhance supply chain resilience and complement the quantitative findings.

5. Results

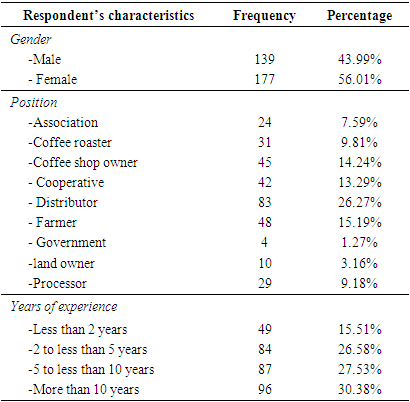

5.1. Demographics Information

5.2. Results of Reliability and Validity

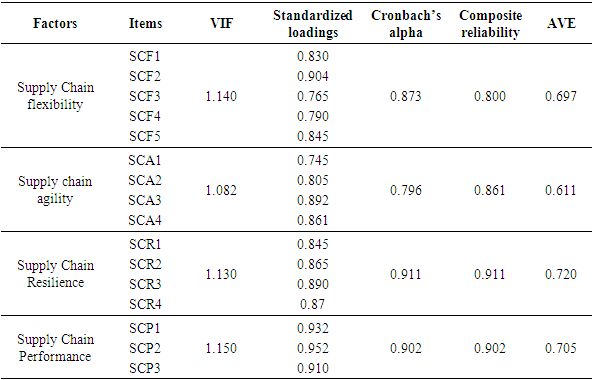

- Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) are used to test an item’s reliability. The values of these two measures should be greater than 0.70. Validity, on the other hand, is measured using convergence through items’ standardized loadings and discriminant validity by the average variance extracted (AVE). Standardized loadings should be higher than 0.70, and AVE values should be higher than 0.50 [28], [56], [16]. The results in Table 2 confirm that the criteria of reliability and validity are met. Both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values were higher than 0.70, all factor loadings were greater than 0.70, and AVE values were greater than 0.611. In terms of collinearity statistics, as measured by a variance inflation factor (VIF), the results indicate that VIF values for supply chain flexibility, supply chain agility, supply chain performance, and supply chain resilience are above 0.80, confirming the reliability of each factor.

|

5.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

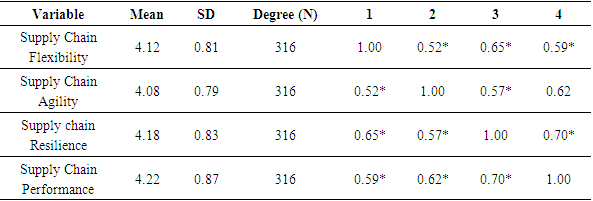

- The results in Table 3 show that the means of the variables are around 4.00, indicating generally positive perceptions of flexibility, agility, supply chain resilience, and supply chain performance. The SD values are moderate, indicating a reasonable spread of responses, and significant positive correlations exist between supply chain flexibility, agility, and resilience, supporting the idea that enhancing these factors strengthens resilience and performance. Flexibility and Agility also correlate significantly with performance (r =0.59* and r = 0.62*), confirming their mediating influence. Using descriptive statistics, one can analyze central measures (mean) and dispersion levels (standard deviation) to obtain essential data distributions and understand survey participants' perceptions of research constructs. The survey results demonstrate positive perceptions from respondents regarding the construct's Flexibility, Agility, Resilience, and Performance because the mean values exceed 4.0 for each construct. The respondents view the performance within Rwanda's coffee industry as high since the mean score reaches 4.22. respondents expressed similar opinions about the constructs based on the results, which show SDs under 1.0. The consistent response patterns are vital because they show that participants share similar opinions regarding supply chain resilience, the agility of supply chain operations, and their overall performance. When assessing Rwanda's coffee industry supply chain environment, most respondents agreed it exists in a positive state, although they recognized the need to improve the agility and flexibility capabilities that support resilience. The matrix analysis demonstrates the exact strength of connections between constructs. A correlation value exists between -1 and 1 The relationship between two variables shows a positive correlation when an increase in one variable results in simultaneous growth of the other variable. Closer to 1 = strong positive relationship, Closer to 0 = weak or no relationship, Key Correlations in Study Resilience ↔ Performance (r = 0.70) Within this relationship, a positive increase in resilience leads to enhanced performance outcomes.

|

5.4. Research Structural Model

- Figure 2 and Table 2 present the results of the PLSM-SEM analysis carried out on the research model. Convergent validity pertains to the consistency of measurements across different operationalizations. [57], [58]. According to Table 3, the items that are predominantly above 0.7 and composite reliability (CR) have been determined to be 0.7 [58], [59]. We assessed the standard errors and T-values of the path coefficients using bootstrapping [58], [59], [60]. The average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.6 with the acceptance threshold. [61], [58], [62].

| Figure 2. Research structural model |

5.5. Fornell-Larcker Criteria

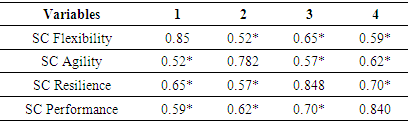

- Table 4 displays the inter-factor correlation matrix that was created to assess discriminant validity. [63], [59]. The [63], Criteria were utilized to gather strong evidence of appropriate discriminant validity to meet this criterion; The square root of the AVE is compared against all construct correlations. Specifically, the results indicate that discriminant validity is achieved. Using the Fornell-Larcker criteria. The independence of the dimensions is referred to as discriminant validity.

|

5.6. Hypotheses Test Results

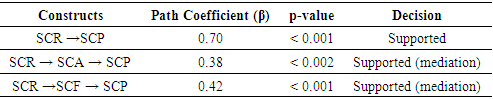

- The hypothesis test reveals supply chain performance exhibits a significant positive impact from supply chain resilience (H1: β = 0.70, p < 0.001) while supporting the previous table, indicating a strong relationship between these variables. The study investigated mediation effects regarding supply chain agility and flexibility, which demonstrated strong outcomes (H2a: β = 0.38, p = 0.002) and (H2b: β = 0.42, p = 0.001), respectively, for their mediating abilities regarding resilience and performance. Data analysis demonstrates that resilience performs stronger in boosting performance because both agility and flexibility work together to accomplish this result as predicted by the conceptual model. All studied relationships display statistical significance with their p-values below 0.05. The data points match the findings of the validity and reliability assessments conducted using the Fornell-Larcker criteria table and Standardized factor loadings. The hypothesis testing will evaluate how indirect performance modifications through agility and flexibility are made. The data outcomes assist in confirming or rejecting the proposed hypotheses.H1: Resilience → Performance, Path Coefficient (β = 0.70, p < 0.001) Strong direct effect. Statistical significance reaches a p-value less than 0.001, which helps us deny our initial hypothesis. Supply chain resilience has a substantial effect on performance levels within Rwanda's coffee industry.The study shows resilience leads to agility, which promotes performance during the mediating process (H2a) Indirect Effect (β = 0.38, p = 0.002). Performance is partially linked to the relationship between resilience, agility, and performance. The evaluation of the p-value revealed both statistical significance and the vital importance of agility in strengthening this relationship.Resilience acts as an influential factor for performance through a medium pathway of flexibility (H2b). Indirect Effect (β = 0.42, p = 0.001). The mediating effect between resilience and performance gets boosted through the flexibility factor, which demonstrates both statistical significance and a strong indirect effect. Performance results from significant direct and indirect pathways, according to the path coefficient analysis. Resilience maintains its relationship with performance no matter how flexibility and agility are factored in, yet these measures increase the relationship strength.The findings demonstrate why organizations must establish resilient supply chains that combine agility and flexibility as performance-enhancing elements in Rwanda's coffee sector. In this table, all diagonal values exceed their respective correlation coefficients, indicating that each construct is statistically distinct. Supply chain resilience strongly correlates with performance (0.70), but its AVE squared root (0.848) remains higher, confirming validity. Similarly, flexibility and agility (0.52) and resilience and agility (moderate correlations.)

|

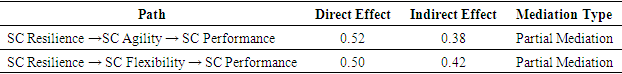

5.7. Summary of Mediation Effect

- To understand the mediating impact of constructs such as SCF and SCA in the model, the hypothesized relationship between H2a and H2b was tested, and the effect was calculated. Supply chain performance shows a strong independent contribution (β = 0.70) from supply chain resilience according to the mediation result Supply chain agility (β = 0.38) and supply chain flexibility (β = 0.42) co-mediate the relationship between supply chain resilience and performance outcome. Supply chain resilience functions independently to drive performance, yet other factors, such as agility and flexibility, enhance its impact, resulting in improved supply chain efficiency and adaptability. The direct effects of resilience remain meaningful, which allows researchers to identify the mediation as partial because resilience plays a vital part on its own, though increased flexibility and agility enhance its power. The study findings validate the results obtained from the correlation matrix, reliability and validity assessments, and hypothesis testing, which underline the vital role of agility and flexibility in enhancing supply chain resilience performance in the Rwandan coffee industry.

|

5.8. Discussion and Conclusions

- The research investigated how supply chain resilience (SCR) affects supply chain performance (SCP) within Rwandan coffee. Sector alongside supply chain agility and flexibility as mediator variables. Organizations implementing stronger resilience strategies show better operational results according to the results (β = 0.70, p < 0.001). Research findings showed that performance rates increased because Resilience received additional enhancement from Both agility (β = 0.38, p = 0.002) and flexibility (β = 0.42, p = 0.001) As the mediating effect, the robustness of resilience as a performance. The concept of determinant remains constant in practice, while agility, together with flexibility, leads to superior performance results. Multiple studies [14], [64] validate that resilient supply chains function better during disruptions and perform more excellently. Flexible business strategies demonstrated (0.65*) positive alignment with supply chain resilience as well as (0.62*) equivalent levels of high performance in the surveyed organizations. The empirical findings of this research validate SCR’s positive influence on SCP while showing agility together with flexibility as intermediate factors that enhance market-based adaptability. Industrial firms operating in Rwanda’s coffee sector need to enhance their capacity to resist risk since climate-related events and worldwide supply chain instability happen more often. The research paper brings multiple new analytical elements to the supply chain resilience investigation, and the Rwandan coffee sector industry serves as a key contribution.1. The study investigates the Rwandan coffee sector industry and serves as one of the first datasets for empirical analysis that demonstrates the relationship between resilience practices and agricultural economic performances. 2. Analysis of this research differs from this study to investigate resilience separately as it demonstrates the interdependence of agility and flexibility for better supply chain resilience and performance, thus building a stronger theoretical foundation of supply chain processes.3. This research supplies a usable model that provides data-based guidance for firms and government agencies to invest in resilience together with flexibility and agility. The outlined framework serves supply chain management professionals who must work in unstable market environments.4. The research amalgamates resilience, agility, and flexibility into a unified model that enhances the existing supply chain literature and develops practical solutions to handle supply chain challenges in dynamic sectors.The research confirms that supply chain responsiveness enhances supply chain performance while proving that agility and flexibility function as critical mechanisms in achieving this result. Research outcomes offer developing economies implementing strategies to construct sustainable supply chains that adapt and perform well against escalating global and environmental uncertainties.

5.9. Recommendations

- The research provides essential theoretical recommendations and practical insight and management application. The Rwandan government should begin by instituting teaching programs that will instruct both producers and logistic suppliers alongside local stakeholders about implementing agile delivery networks and flexible procurement methods. A combination of financial incentives, including subsidies, low-interest loans, and tax breaks, should be implemented to stimulate coffee producers and cooperatives toward adopting these resilience-building strategies. Climate-related policies need to become integrated with supply chain resilience strategies to ensure coffee producers have solutions for upcoming climate changes. The market and climate disruptions should be addressed by industry practitioners through agile logistics systems, flexible sourcing practices, and advanced demand forecasting, which can enable fast supply and demand adjustments while weakening dependency on single suppliers. Supply chain managers should build predictive analytics systems along with early-warning protocols and adopt IoT technologies and AI-based analytics with big data applications to monitor operations in real-time, which raises supply chain agility and operational flexibility. The supply chain requires collaboration between companies, which demands the implementation of supplier and distributor information-sharing practices to develop mutual resilience. The findings support the Dynamic Capabilities Theory [65]. Resilient capabilities allow companies to respond dynamically to disruptions, thereby proving why agility and flexibility boost performance outcomes. Organizations must develop dynamic capabilities that enable them to effectively handle market opportunities and challenges that appear before them. Policymakers, along with industry managers, should implement these recommendations to secure the lasting performance stability and adaptability of Rwanda's coffee industry against climate-related and market disturbances.

6. Limitations and Future Research

- This research investigation contains several limitations, even though it generated notable contributions. The research analyzes the Rwandan coffee industry exclusively, which creates barriers to broader application to other fields across the nation. The framework needs future application to different agricultural supply chains to establish quotative proof of its general use potential. A cross-sectional study approach was used by the research, although this design restricts our understanding of enduring resilience patterns. Longitudinal research design would deliver time-sensitive information about resilience capability development patterns. Additional investigation of the resilience performance relationship through other partners and sustainability practices and technology adoption necessitates future research because this study concentrated on agility and flexibility as mediators.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I extend the most heartfelt thanks to my supervisor, Wan Li, because their essential help, motivation, and constant backing were fundamental to my research experience. I deeply appreciate the support given to me by My family, along with their boundless love and patience, and my friends, who consistently provided worthwhile Discussions that nourished me both intellectually and emotionally. Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications (CQUPT) receives my heartfelt gratitude for delivering academic resources and an educationally stimulating atmosphere that enabled this research to succeed. My gratitude extends to all individuals who have either directly or indirectly supported this research because their guidance led to this achievement, which could not exist without their contributions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML