-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2019; 8(2): 25-34

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20190802.01

Strengthening the Effectiveness of the Procurement Function in the Public Sector

Jean Bosco Nzitunga

Administration and Operations; International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR)

Correspondence to: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Administration and Operations; International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

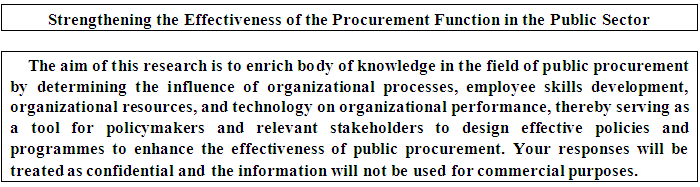

Every organization, whether it is a manufacturer, wholesaler, or retailer, buys materials, services and supplies to support operations. For the past few years, the public procurement system in Namibia has steadily evolved from a crude system with no regulations to an orderly legally regulated procurement system currently in use. Despite heightened interest by both scholars and practitioners in studying and better understanding the importance of effective public procurement and its determinants, limited research has so far been conducted in this regard in the Namibian context. A review of the literature in this regard revealed a research gap that culminated in the following research question: what is the impact of organizational processes, employee skills development, organizational resources, and information technology (IT) on public procurement effectiveness in Namibia? To address this research question, a questionnaire survey based on the Likert scale was administered to 100 procurement employees from the 25 current Namibian Government ministries in Windhoek.

Keywords: Procurement, Effectiveness, Public sector

Cite this paper: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Strengthening the Effectiveness of the Procurement Function in the Public Sector, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2019, pp. 25-34. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20190802.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Public procurement is an area that is prone to mismanagement, corruption, and vendors’ ploys. In Namibia, the public procurement process is often disputable due to unfairness and lack of transparency in tender awards procedures. Moreover, many public organizations experience difficulties during pre-qualifications, staging competitive procurement process, warehousing supplies, carrying out quality assurance, clearing at customs, over and under-invoicing in imports and local procurements, and availing adequate finances equivalent to sourced resources (Savage, Fransman, and Jenkins, 2013). Other challenges include inadequate trained staff in procurement department, poor sensitization or training to tender committee members, and influence from external stakeholders and the size of the institution.The government of Namibia has long realized the importance of the public procurement function, its role in the economic development of the country, and its contribution to poverty reduction. In light of the above, the government has initiated a number of procurement reforms in its public procurement system with the aim of making it more efficient and transparent in line with requisite and basic procurement guidelines and best practices, but in many ways, trying to make it more focused on economic development and poverty reduction (Savage et al., 2013). Addressing the Permanent Secretaries of his Government Ministries in 2010, former Namibian President Pohamba emphasized that public procurement in Namibia is characterized by numerous inefficiencies and underlined the need for enhanced performance in this regard (Weidlich, 2010). He stressed that public procurement should be used as core strategy to address unemployment through the creation of new jobs and retention of existing ones, and creating opportunities for the SME sector development (Weidlich, 2010). Despite these government efforts in reforming public procurement and the resulting improvement performance in this regard, public procurement sector is still facing a number of challenges which include - inter alia - corruption and weak integrity and poor enforcement mechanisms in the public procurement system; limited financial capacity and inadequate human resources to effectively and efficiently manage public procurement functions; lack of public procurement professional development plan and strategy; absence of coordinated mechanisms of ensuring value for money and poor quality assurance frameworks as well as control mechanisms to ensure effective administration of procurement process; and poor enforcement of public procurement monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (Savage et al., 2013). Moreover, market dynamics have created challenges for many public organizations and some of the key challenges affecting public organizations include the emergence of the global economy advancement in the technology, increased societal demands, organizational scrutiny by pressure groups and more so the heightened media attention that is critical of government inefficiencies in service delivery (Savage et al., 2013).Several scholars have underlined that interactions between various elements, professionalism, staffing levels and budget resources, procurement organizational structure whether centralized or decentralized, procurement regulations, rules and guidance and internal control policies, all need attention and influence the performance of the procurement function (Thai, 2011; Neals, 2011). In addition, public procurement is faced by challenges imposed by a variety of environment factors (external factors) such as market, legal environment, political environment, organizational and socio-economic environmental factors (Musanzikwa, 2013). However, little research has been conducted in this regard in the Namibian context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Procurement Effectiveness

- On this study, the effectiveness of public procurement is assessed by organizational performance in procurement, which refers to a set of financial and non-financial indicators which offer information on the degree of achievement of procurement objectives and results (Jenatabadi, 2015, p.3). This means the organization’s effectiveness and efficiency in (i) setting procurement standards, specifications, objectives, and goals and achieving them; (ii) ensuring satisfaction of all relevant stakeholders; and (iii) enforcing applicable procurement policies and regulations. Historically, purchasing has been perceived as a clerical or low-level managerial activity charged with responsibility to execute and process orders initiated elsewhere in the organization. The role of purchasing was to obtain the desired resource at the lowest possible purchase price from a supplier. This traditional view of purchasing has changed substantially in the past several decades. As a result, procurement has been elevated to a strategic activity (Brown et al., 2013). Public procurement means an acquisition, whether under formal contract or otherwise, of works, supplies and services by public bodies using publicly sourced finances. It involves the purchasing, hiring or obtaining by any contractual means of publicly needed goods, construction works and services by the public sector. It also includes situations in which public funds are mobilized to procure works, goods and services even if the government does not get directly involved (De Mariz, Ménard, and Abeillé, 2014). Public procurement must be transacted with other considerations in mind, besides the economy. These considerations include accountability, non-discrimination among potential suppliers and respect for international obligations. Lack of public confidence and trust in the governments’ ability to effectively and efficiently procure its goods and services has been often the subject of headlines (Handfield, 2011). It is asserted that each time a new case of fraud and abuse has occurred, a new legislation and regulation has been implemented to address the particular problem. As a result, over the years a specialized way of doing business has built up based on volumes of legislation, regulations and practice. The resulting unique government system has unfortunately not achieved the desired objectives of effectiveness and efficiency (Arora, 2014). For these reasons, the effectiveness of public procurement is imperative in all countries in order to protect public interests. Unlike private procurement, public procurement is a business process within a political system and has significant consideration of integrity, accountability, national interest and effectiveness (Handfield, 2011). Procurement as one of the components of the overall organizations Supply Chain (SC) need to be effective as well as efficient. Procurement processes experience challenges world over. This occurs even in developed countries and some of the challenges are related to internal and external factors as well as poor communication between departments. Arora (2014) emphasizes that in the past few years, global sourcing has been more of an economic as well as a political agenda, to many large corporate. As time goes by, more and more companies find that the supply chain issues associated with an outsourcing program have often been under estimated. He further asserts that the crux of the problem is that many seemingly smart outsourcing decisions were based on low acquisition or procurement cost, rather than total supply chain cost. Thai (2011) identified the following seven challenges facing the public sector procurement: (i) setting of clear objectives at the outset of all projects and for all strategic procurement units; (ii) developing a procurement strategy for every public sector organization; (iii) focusing strategic procurement on outcomes not processes; (iv) embracing collaboration as a strategic tool; (v) recognizing that sustainability has become a strategic driver for professional procurement; (vi) positioning the public sector as a customer of choice, and (vii) resolving the talent scarcity problem. For Handfield (2011), the main challenges in public procurement include factors such as the fear for negative publicity that has led to a growing emphasis on the legal aspects of the tendering process; the fact that the procurement department acts in a reactive way and is often not involved until the specifications have been defined; the fact that procurement is seen as an operational department and not perceived as an advisor or partner of the organization; the fact that procurement is organized around contracts rather than commodities; the fact that there can be peak moments when contracts are about to expire, but no continuous process to manage internal and supply market developments and opportunities; and the fact that there is no focus on managing the end to-end process and closing the procurement loop (Handfield, 2011).Public procurement practitioners have always walked on a tight rope. Their ability to accomplish procurement objectives and policies is influenced very much by internal forces including interactions between various users from different departments demanding different goods and in most cases are not predictable (Arora, 2014). Staffing levels and budget resources are some of the possible challenges considering the fact that funds are not available at the time of planning. Procurement planning enables departments to anticipate recurring contract requirements and be in a better position to take anticipatory actions aimed at ensuring compliance, but in most cases the plan is not achieved due to lack of sufficient funds (Arora, 2014, Handfield, 2011; Thai, 2011; Neals 2011).Another challenge identified by the literature is excessive documentation. Public procurement is usually characterized by too much paper work which is meant to communicate information from one function to another in order to facilitate action, to indicate requirements to suppliers, and to obtain the necessary goods and services timely and according to specifications (Baily et al., 2008). To address this problem, Baily, Farmer, Crocker, Jessop, and Jone (2008) recommends the use of e-procurement in the public sector. On their part, Lewis and Roehrich (2009) put an emphasis on the importance of supplier selection. They stress that selecting the right suppliers has an immediate and long-term effect on the organization’s ability to serve its clients. A wrong supplier may supply poor goods or sub-standard materials which will then lead client poor customer service or may result in delays and may require extensive corrective work, thereby affecting the product or service cost. Supporting this argument, Thai (2011) underlines that relationships with suppliers can be strained as a result of poor communication. He stresses that suppliers often complain that they are kept at arm’s length and not informed about projected needs, but are still expected to deliver on time no matter what the level of demand. Another aspect discussed by Thai (2011) is the legal framework. He underlines that apart from public procurement regulations and rules, the procurement function needs to consider a range of legal aspects including research and development (regulations dealing with safety and health of new products), manufacturing (safety and health regulations at workplace and pollution control), finance (regulations dealing with disclosure of information), marketing (regulations dealing with deceptive advertising, disclosure of product characteristics), personnel (regulations dealing with equal opportunity for women and minorities) and contracts (Thai, 2011).It is imperative that management recognises weaknesses in the procurement function and adjust to the dynamic global environment and socio-economic changes. Effective buying involves six “rights”: buying goods and services at the right price, from the right source, in the right quantity, at the right time, at the right specifications that meet users’ needs and to the right internal customer (Handfield, 2011). Researchers (such as Thai, 2011; Neals 2011) noted that the performance of the procurement function is influenced by the interactions between various elements including professionalism, staffing levels and budget resources, procurement organizational structure, procurement regulations, rules and guidance and internal control policies.

2.2. Organizational Processes

- Organizational processes can be broadly defined as structured, measured sets of activities that together - and only together - transform inputs into outputs (Dumas, La Rosa, Mendling, and Reijers, 2013). In contemporary organizations, organizational processes have become one of the most important - if not the most important - management paradigm (Jenabati, Huang, Ismail, Satar, and Radzi, 2014, p.108). By providing adequate information flow – both vertically and horizontally, organizational processes are a vital element in ensure that an organization’s goals are effectively achieved (Dumas et al., 2013, p.4).Procurement professionals should develop integrated purchasing processes that support organizational goals and objectives. According to Handfield (2011), these strategies involve: developing and maintaining policies and processes; monitoring supply markets and trends in terms of material prices, supply shortages and supplier changes; and interpreting the effect of these trends on company strategies supporting the organization’s need for a diverse and globally competitive supply base by identifying the critical materials and services required to support company strategies in key performance areas – predominantly during new product development. Although the effectiveness of organizational processes is constantly associated with improved organizational performance, few studies have empirically investigated that relationship. The study by Jenabati et al. (2014, p.119) which was aimed at exploring the correlation between effective organizational processes and improved organizational performance found that processes are essential in fostering an environment of reduced conflict and increased connectedness in an organization, thereby enhancing organizational performance. A surprisingly strong association was revealed by the findings of their study between organizational processes and overall performance. Bearing in mind all the dynamics that can possibly affect organizational performance, these findings are compelling (Jenabati et al., 2014, p.120). Moreover, the study of Dumas et al. (2013) underscored a positive link between organizational processes and organizational outcomes. On the other hand, recent experiences have shown that – subject to the prevailing balance between an organization’s environment and its organizational structure, the management of organizational processes is yielding varying success. Expressed differently, this means that it is not true that process transformation results in improved performance. Several organizations have discovered that sometimes even intense levels of process enhancement do not always lead to enhanced organizational performance (Radzi, Huang, Jenatabadi, Kasim, & Radu, 2013, p.1154). All the above-mentioned underlines the need to consider organizational processes as one of the important determinants of public procurement effectiveness (performance).

2.3. Skills Development

- Skills development denotes the “planned and systematic modification of behaviour through learning events, programmes and instruction, which enable individuals to achieve the levels of knowledge, skill and competence needed to carry out their work effectively” (Jehanzeb and Bashir, 2013, p.246). According to Hameed and Waheed (2011, p. 227) and Jehanzeb and Bashir (2013, p.247) skills development is concerned with the development of people’s expertise and knowledge. Skills development has also been referred to as a situation where an expert works with a learner to transfer to them certain area of knowledge and skills in order to improve current job (Hameed and Waheed, 2011, p.226). Irrespective of how long one has been working for a certain organization, sustained skills development can be a crucial element for the enhancement of employee’s effectiveness (Jehanzeb and Bashir, 2013, p.244). What is interesting is the planned characteristic of process which is underlined by Hameed and Waheed (2011, p.226) with regards attitude modification, knowledge improvement, and skill or behaviour adjustment through learning involvements for the achievement of enhanced performance. Through the process of skills development, employees acquire new – and enhance their existing – skills, practises and approaches which help them to establish and maintain their jobs. The focus of several programs of employee skills development is novel skills, methods, and notions that may have unknown or unavailable at the time of initial recruitment. However, effective programs in this regard need to not only focus on job-related skills but also emotional reinforcement to handle wide-ranging circumstances (Hameed and Waheed, 2011, p.227). For example, one important aspect that should be emphasized is confidence-building as this can be beneficial in all aspects of one’s life. It has been demonstrated that organizations invest adequately in programs of employee skills development enjoy improved organizational performance (Jehanzeb and Bashir, 2013; Hameed and Waheed, 2011).Personnel handling the procurement function should exhibit a high level of purchasing knowledge and skills (Neals, 2011). They should be qualified and possess the skill to examine and interpret supply and demand changes as well as handle aspects of relationships with suppliers. Lack of updated knowledge and skills towards local and international purchasing is a risk because it may destroy the firm’s relationship with other immediate stakeholders such as customers, the production department and suppliers, to mention a few. Unprofessional practices in purchasing might result in poorly handled orders and shipments, which may lead to unnecessary expenses, delays, anger and frustration and are a reflection of organisational incompetence and untrustworthiness (Neals, 2011). Organizations that commit adequate investment in employee skills development achieve enhanced productivity, quality, and performance (Evans and Lindsay, 1999).

2.4. Organizational Resources

- Organizational resources simply refer to “assets, knowledge, capabilities, and process of an organization” (Ombaka, Awino, Vincent, Machuki, and Wainaina, 2015, p.13). Organizational resources are subdivided tangible or intangible categories. The category of tangible resources consists of physical and financial assets such as land, machinery, furniture and capital (Jugdev and Mathur, 2012, p.107). Intangible resources include brand name; reputation of the organization; knowledge, skills, experiences of employees, as well as organizational procedures. As advanced by Kapoor and Kansal (2003, p.4), when an order is placed, a number of different costs can be incurred while processing and handling the order. Procurement costs include the cost of processing an order through the accounting and purchasing department, transmitting the order from the supplier, transporting the order when transportation charges are not included in the purchased goods and material handling or processing of the order at the receiving dock. For international buying it may be difficult for most procurement organisations engaged in international trade to fulfil their obligation to meet all the procurement requirements stipulated in the purchasing contract because of limited foreign currency (Hypo Group Alpe-Adria, 2010). International buying involves large cash transactions and is associated with high procurement costs. Procurement professionals may be forced to reduce their order as a result of these costs. However, this decision may result in failure to meet the demand of goods and services in the receiving country (Hypo Group Alpe-Adria 2010). Thus, procurement professionals must be able to predict the level of costs associated with international buying. Strategic management academics have underlined the influence of an organization’s resources on its performance (Barney, 1991; Marino, 1996).

2.5. Information Technology

- Information Technology (IT) is a broad subject concerned with all aspects of managing and processing information, especially within a large organization (Jean, Sinkovics, and Kim, 2008, p.564). While IT is often used to describe computers and computer networks, it actually includes all layers of all systems within an organization, from the physical hardware to the operating systems, applications, databases, storage, servers and more. Telecommunication technologies, including Internet and business phones are also part of an organization's IT infrastructure (Jean et al., 2008). Technology is a dynamic process. Changes in technology are associated with high set-up costs. Financial constraints are a major drawback, especially in some developing economies, when it comes to capital projects. Modern procurement is now taking place online (Savage et al., 2013), yet many companies in developing economies are still lagging behind. For instance, most procurement functions in Namibia and Zimbabwe are still being done manually. Poor infrastructure, weak strategic alliances and reluctance to change have resulted in poor or even non-adoption of such technologies as electronic data interchange (EDI) in these two countries (Savage et al., 2013). In their study, Jean et al. (2008) found evidence that IT capabilities directly contribute directly to improved organizational processes such as coordination, transaction-specific investment, absorptive capacity and monitoring; and this in turn contributes to strategic and operational performance outcomes.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

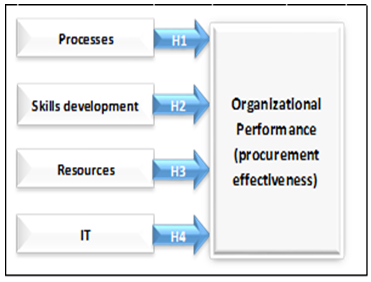

- This study seeks to deepen our understanding in field of public procurement by proposing and testing a model which advances organizational processes, employee skills development, organizational resources, and technology as determinants of the procurement function’s effectiveness in the public sector. Figure 3.1 presents the research model.

| Figure 3.1. Research Model (adapted from Nzitunga, 2015) |

4. Methodology

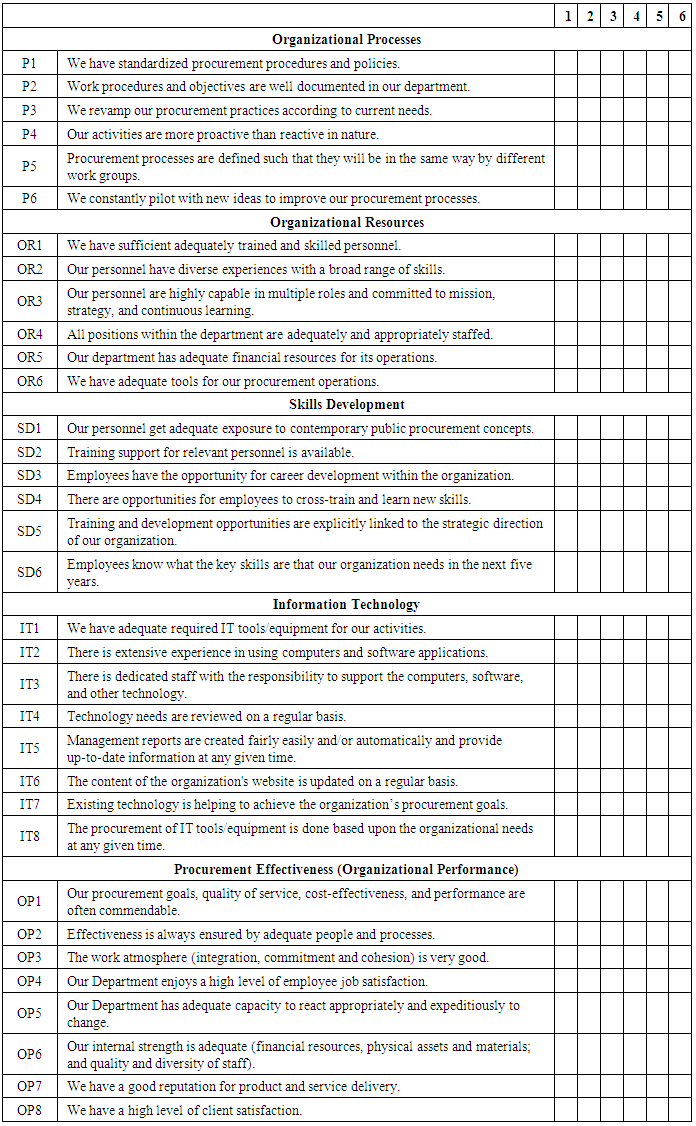

- This was a quantitative study. Based on purposive sampling, sample of 100 respondents was selected by randomly choosing four (4) procurement employees from each of the 25 Government ministries. According to Palys (2008, p. 396), a “purposive sample is a non-probability sample that is selected based on characteristics of a population and the objective of the study.” The variables were measured using a 6-point Likert scale which provided response categories for respondents to rate their answers to statements, making the questions simple to answer. The data collection was done using online “SmartSurvey.”

4.1. Validity and Reliability

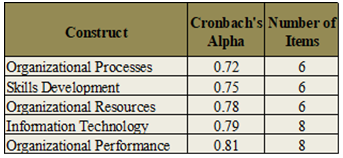

- Validity refers to the extent to which a measure or set of measures correctly represent the constructs of the study (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Scheepers, 2007).This study used face validity which was achieved through a thorough literature review and by developing and using theoretical definitions and validated measurement instruments from previous studies (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Scheepers, 2007). Face validity is established when the measurement items are conceptually consistent with the definition of a variable, and this type of validity has to be established prior to any theoretical testing (Cooper & Schindler, 2006). Reliability is an assessment of degree of consistency between multiple measurements of the same variable. It is, therefore, concerned with whether alternative measurements at different times would reveal similar information. Variables differ in how well they could be measured - i.e. how much measurable information their measurement scale is able to provide. There is some measurement error involved in every measurement, which determines the ‘amount of information’ that can be obtained (Bhattacherjee, 2012). Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of a score from a measurement scale, i.e. whether the results in the survey could be duplicated in similar surveys (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Scheepers, 2007). Reliability is said to be particularly important when latent variables are calculated from underlying item scales. Since these scales consist of a group of interrelated items designed to measure underlying constructs, it is important to establish whether the same set of items would extract the same responses if they were re-administered to the same sample group on more than one occasion. Variables derived from test instruments are only said to be reliable when it is clear that they elicit stable responses over multiple measurements of the instrument surveys (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Scheepers, 2007).Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as a measure of internal consistency-reliability of the scale used in this study. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal reliability for multi-item summated rating scales. Its values range between 0 and 1, where the higher the score, the more reliable the scale. The research instrument used for this study was reliable as shown in Table 4.1.

|

5. Findings and Discussion of Results

- The descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations to describe the different variables in this study. Spearman correlations were used to determine the relationships between the different variables, as the collected data were ordinal. Finally, Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was used to test the multivariate relationships hypothesised by the research model.

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

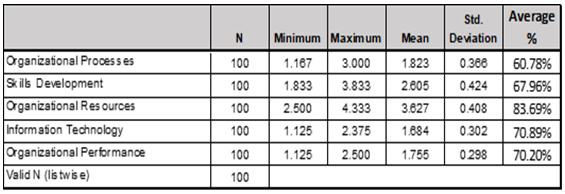

- The perceptions about organizational processes, employee skills development, organizational resources, information technology (IT), and public procurement effectiveness are described in this section. A composite score was obtained for each variable by totalling the individual scores of the relevant items and calculating the average. Descriptive statistics of the composite variables are summarized in Table 5.1.

|

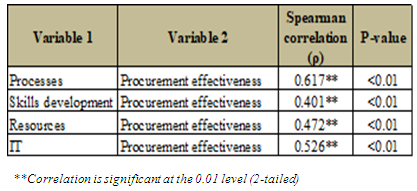

5.2. Correlations

- The relationships among the study variables were assessed using Spearman's correlation. Table 5.2 summarises the Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values for the different variables.

|

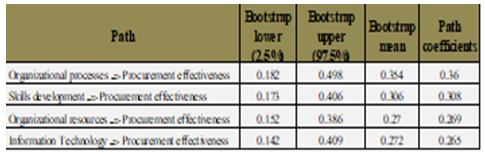

5.3. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression Analysis

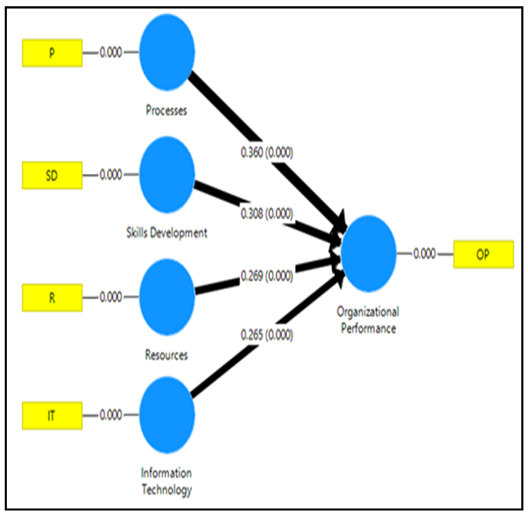

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) is a method for constructing predictive models when the factors are many and highly collinear (Abdi & Williams, 2013). The term “latent” does not have the same technical meaning in the context of PLS as it does for other multivariate techniques. In particular, PLS does not yield consistent estimates of what are called “latent variables” in formal structural equation modelling (Maitra & Yan, 2008; Abdi & Williams, 2013). The bootstrap, used in this study, aims to carry out familiar statistical calculations, such as standard errors, biases, confidence intervals among others, in an unfamiliar way by purely computation means, rather than through the use of mathematical formulas (Abdi & Williams, 2013). A comprehensive base of mathematical theory has grounded the development of bootstrap methods; however, that is beyond the scope of this study. The bootstrap confidence intervals utilised to gauge the statistical significance for the paths and path coefficients are presented in Table 5.3 below.

|

| Figure 5.1. Path, strength and significance of the path coefficients assessed by PLS (n=100) |

5.4. Summary of Key Findings

5.4.1. Influence of Organizational Processes on Procurement Effectiveness

- The first hypothesis, namely that there is a positive association between organizational processes and public procurement effectiveness in Namibia, was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.360). These findings are consistent with the literature in Section 2. The managerial implications are that ensuring that public procurement is characterized by standardized procedures and policies; documented work procedures and objectives; revamping of practices according to current needs; proactiveness; effective process design; and constant process improvement will lead to enhanced regular commendable outputs; effectiveness ensured by adequate people and processes; conducive work atmosphere; high level of employee job satisfaction; adequate capacity to react appropriately and expeditiously to change; adequate internal strength; good reputation for product and service delivery; and high level of client satisfaction - i.e. enhanced public procurement effectiveness.

5.4.2. Influence of Skills Development on Procurement Effectiveness

- The hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between employee skills development and public procurement effectiveness in Namibia, was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.308). This means that appropriated exposure to contemporary public procurement concepts; training support for relevant personnel; opportunity for career development within the organization; opportunities for employees to cross-train and learn new skills; training and development opportunities linked to organization’s strategic direction; and future organization’s skills needs knowledge by employees will contribute in enhancing public procurement effectiveness in Namibia. This is also in line with the literature reviewed in Section 2.

5.4.3. Influence of Organizational Resources on Procurement Effectiveness

- The third hypothesis, namely that there is a positive link between organizational resources and public procurement effectiveness in Namibia, is confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.269). These findings are consistent with the literature in Section 2. The managerial implications are that the availability of sufficient adequately trained and skilled personnel; personnel with diverse experiences and skills; capable personnel in multiple roles and committed to mission, strategy, and continuous learning; all positions adequately and appropriately staffed; adequate financial resources; and adequate operational tools will lead to improved organizational performance in Namibian public procurement.

5.4.4. Influence of Information Technology on Procurement Effectiveness

- The hypothesis which postulated that Information Technology (IT) is likely to be positively associated with public procurement effectiveness in Namibia, was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.265). What this implies is that adequate required IT tools/equipment; extensive experience in using computers and software applications; dedicated staff with the responsibility to support the computers, software, and other technology; technology needs reviewed on a regular basis; user-friendly creation and generation of management reports; organization's website is updated on a regular basis; existing technology helping to achieve the organization’s goals; and procurement of IT tools/equipment done based upon the organizational needs at any given time will enhance the public procurement effectiveness in Namibia.

6. Summary

- The effectiveness of public procurement is imperative in all countries in order to protect public interests. Unlike private procurement, public procurement is a process within a political system and has significant considerations of integrity, accountability, national interest and effectiveness. Given the dearth of literature in this regard in the Namibian context, this study has supplemented the body of knowledge in the field of public procurement by determining the influence of organizational processes, employee skills development, organizational resources, and technology on organizational performance, thereby serving as a tool for policymakers and relevant stakeholders to design effective policies and programmes to enhance these aspects.

7. Conclusions

- The findings of this study show that organizational performance is positively influenced by organizational processes, employee skills development, organizational resources, and information technology. The study also found that, except for organizational resources, the respondents were not satisfied with the current organizational processes, employee skills development, and information technology in public procurement. Unless organizational strategies are designed in such a way that they enhance the factors, the objectives and goals of the organization cannot be adequately achieved. In light of the findings of this study, managerial interventions should focus on ensuring adequate processes, sustained employee skills development, resources, and information technology. Corrective and remedial steps that could be immediately adopted include but are not limited to the following: strategic planning incorporated into all stages and aspects of public procurement; ensuring key personnel have the required and relevant academic or professional training in the aspects of public procurement; comprehension of contemporary public procurement concepts and principles by the top management of relevant department/ministry; objectively measuring performance in terms of public procurement activities; and ensuring that information technology effectively supports contemporary public procurement.It is hoped that by assessing the current public procurement practices in the public sector, it will generate an increasing desire on the part of the policy-makers and managers to shift traditional public procurement outlook towards a more strategic, comprehensive, and modern public procurement approach.

Appendix 1: Research Questionnaire

For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML