-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2019; 8(1): 14-24

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20190801.02

Assessing the Influence of Logistics Outsourcing Practices on Organizational Performance in the Mining Industry

Jean Bosco Nzitunga

Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR)

Correspondence to: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The emergence of globalization has made outsourcing to become one of the widely embraced business strategies for delivering outstanding services to consumers in both private and public organisations. While a number of scholars have analysed the concept of outsourcing and its influence on organizational performance, little research has been conducted in this regard in the Namibian mining industry context. The discovery of this absence of research therefore generated the following question: “what is the influence of logistics outsourcing practices on organizational performance in the Namibian mining sector?” An experimental quantitative research was carried out at one of the biggest Namibian diamond mining companies – namely Namdeb Diamond Corporation – to answer to the above question. The population for this study comprised logistics department employees (including managers and supervisors) at Namdeb Diamond Corporation. The company had a total of 105 logistics employees countrywide and a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to all of them via e-mail. The response rate was 95%. To analyse the collected data, descriptive statistics and inferential statistics (Partial Least Squares regression analysis) were used. The results revealed a positive influence of logistics outsourcing practices on organizational performance in the Namibian mining sector.

Keywords: Logistics, Outsourcing practices, Organizational performance, Mining industry

Cite this paper: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Assessing the Influence of Logistics Outsourcing Practices on Organizational Performance in the Mining Industry, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 14-24. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20190801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Outsourcing – i.e. the strategic use of outside resources to perform activities traditionally handled by internal staff and resources – have received increased attention in management practice around the world over recent decades (Bhattacharya, Singh, and Bhakoo, 2013). The reasons why firms decide to outsource vary, even if the most mentioned motive is often to achieve cost benefits and/or focus on core competencies. These two motives are often interlinked as one argument whereas managers use outsourcing in order to improve the use of capital investments by concentrating the firm’s human and capital resources on its main activities (Quélin & Duhamel, 2003, p.648). Beside these main motives, other reasons for outsourcing mentioned in the literature include the achievement of best practice by acquiring access to external competencies (Kakabadse and Kakabadse, 2002, p.191); transformation of fixed costs into variable costs (Alexander and Young, 1996, p.729); and serving as a tool to adapt to rapidly changing environments (Leavy, 2004). An increase of the firm's internal focus on its core business is often assumed to result in performance improvements, and, as a result, an increased market value. Outsourcing is a management strategy through which a company assigns some non-core functions to more specialized, more effective and more efficient service providers such that the organization can be left to perform and concentrate with the core business activities. Global trends in globalization has contributed to numerous firms outsourcing some of their services to specialized firms in order to give much emphasis on their competitive advantage. Firms are sometimes forced to seek outsourcing services as a result of lacking human resources as they face challenges in getting right skills and knowledge which can make them gain world class capabilities similar to that expected from service provider (Kremic, Tukel, & Rom, 2006, p.469). The outsourcing decision is influenced by the ability of an organization to invest in developing a capability and sustaining a superior performance position in the capability relative to competitors. Processes in which the organization lacks the necessary resources or capabilities internally can be outsourced. Organizations can access complementary capabilities from external providers where they can gain no advantage from performing such processes internally (Irina, Liviu, and Ioana, 2012, p.1067). Outsourcing concept has not received a remarkable attention and support which can be considered to be favourable for improving organization growth and performance in Namibia. The mining industry needs enormous logistical mechanisms and requires a careful management in this regard for effective organizational performance. The core business of a mining company is to extract minerals though they still need to procure materials, manage inventory and transports goods. All these other activities are non-core and can be outsourced so that the mining companies can focus on their core function which is extracting minerals.Although several scholars (Bhattacharya et al., 2013; Njuguna, 2010; Kroes & Ghosh, 2010; Bustinza, Arias-Aranda, and Gutierrez-Gutierrez, 2010) have evidenced a positive influence of logistics outsourcing on organizational performance, there is a lack of research in this regard in the Namibian mining industry context. Hence the need for further empirical studies to mitigate this literature gap.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Outsourcing

- Scholars have defined outsourcing in many different ways. Earlier on, Lonsdale and Cox (2000, p.445) had defined outsourcing as “the process of transferring an existing business activity, including the relevant assets, to a third party.” On their part, Bustinza et al. (2010, p.276) defined outsourcing as the retention of responsibility for the delivery of services by an organization but devolution of the day to day performance of those services to an external organization, under a contract with agreed standards, cost and conditions. For the purpose of this study, outsourcing is defined as “the strategic use of outside resources to perform activities traditionally handled by internal staff and resources” (Bhattacharya et al., 2013, p.399).

2.1.1. Outsourcing Theories

- Outsourcing is based on many theories but this study was guided by the following theories: Resource Based View, Transaction Cost Economics, Core Competency, and Contractual Theory.2.1.1.1. Resource-Based View (RBV) TheoryOutsourcing can be explained from the dimension of relationship between service receiver and service provider. The resource-based view (RBV) analyses other aspects, taking into account internal strengths and weaknesses. A firm’s resource perspective generates the core competencies and competitive advantage for specific business activity, RBV defines resources as tangible and intangible assets within the firm. According to Barney, (1991, p.101), the resource-based view is based on the concept of productive resources. In view of RBV theory of the firm, outsourcing is taken as a strategic decision which can be used to fill gaps in the firm’s resource and capabilities (Grover, Teng, and Cheon, 1998, p.90). Normally firms establish their specific resources which they keep on reviewing in order to respond to shifts in the changing business environment. Hence, firms must come up with dynamic capabilities which are adaptable to the environmental changes (Pettus, 2001, p.880). Capability is the key role of strategic management to ably adapt, integrate and reconfigure internal and external organizational skills, resources and functional capabilities to match the requirements of a changing environment. Combined capability, skills and right resources are necessary ingredients used by service providers to make quality products. RBV theory puts more emphasis on the firm’s internal resource rather than external opportunities and threats created by industry conditions. The theory maintains that in order to generate sustainable competitive advantage a resource must provide economic value and must be presently scarce, difficult to imitate, non-substitutable and not readily obtainable from markets. The theory also relies on two key points; first that resource are determinants of firm performance and second that resources must be rare, valuable, difficult to imitate and non-substitutable by other rare resources. When the latter occurs, a competitive advantage has been created (Priem & Butler, 2001, p.23). 2.1.1.2. Transaction Cost Economic (TCE) TheoryTransaction costs arise from the fact that it is not possible for a firm to completely contract while incomplete contracts create renegotiations when the balance of power between the transacting parties shifts (Williamson, 1979, p.235). The attribute of a firm’s transactions positively associated with transaction costs include the necessity of investment in durable, specific asset, inefficiency of transacting, task complexity and uncertainty, difficult in measuring task performance and interdependence with other transactions. Transaction cost economics (TCE) theory is based on a rational decision made by firms after considering transaction related factors such as asset specificity, environmental uncertainty and other types of transaction cost. Activities conducted under conditions of high uncertainty require specific assets e.g. human and physical capital. Asset specifically refers to the nontrivial investments in transaction i.e. specific assets. On the other hand, transaction cost economics (TCE) or theory view the relationship between service receiver and service provider as a model that allows economic transactions to take place (Reuben, Boselie, & Lu, 2007, p.61). Transaction costs include time, money, human resources, contract issues negotiation matters, risks e.tc. Hence the relationship between service receiver and service providers is closely integrated due to cost considerations (Shaharudin, Zailani, & Ismail, 2014, p.202). However, according to Mclvor, Humphreys, Wall, McKittrick (2008, p.3), the two theories RBV &TCE can be combined to form a combined view through which outsourcing decisions can be based upon as RBV & TCE complement each other.2.1.1.3. Core Competency TheorySimchi-Levi, Keminisky & Simchi-Levi (2004) defined core competency as the collective learning in the organization on how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies. This theory suggests that firm activities should either be performed in house or by external service providers. It is based on make or buy decision. Noncore activities should be considered for outsourcing to the best suited service providers who are experts in that field. However, some few non-core activities which have a big impact on competitive advantage should be retained in house. Core competencies refer to the collective knowledge of the production system concerned in particular knowledge of procedures and how to best integrate and optimize them. The process of outsourcing non-core competencies continues to gain importance as it transfers responsibilities such as maintenance and transport functions, in the hands of suppliers most capable of performing them most successfully (Chandra & Kumar, 2000, p.102). Vendors’ competence is an important factor that influences the success of an outsourcing arrangement (Levina & Ross, 2003, p.333).2.1.1.4. Contractual TheoryFor an outsourcing strategy to be implemented, it requires a legally bound contract which sets the institutional framework in which each party’s rights, duties, and responsibilities are clearly defined. The goals, policies, practices, and strategies on which the arrangement is based are also specified in the contract. The purpose of the outsourcing contract is to facilitate proper exchange of services between the two parties, prevent misunderstanding, prohibit moral hazards in a cooperative relationship, and protect each party’s proprietary knowledge. Properly written contracts prevent risks arising from non-performance and misunderstanding, and also reduces uncertainty likely to be faced by firm decision-making process. The contract sets a procedure for conflict resolution (Luo, 2002, p.904). Legal experts emphasize the need for comprehensive contract which can serve as a reference point specifying how the client and the vendor relate (Kern & Willcocks, 2000, p.16).

2.1.2. Constructs of Outsourcing

- From the literature reviewed, four main constructs of outsourcing have been identified – namely cost reduction, quality improvement, technology adaptation, and risk management.2.1.2.1. Cost ReductionOutsourcing frees up cash thus allowing investments on core activities, improves organization focus, frees management time and reduces staff costs as well as giving more organization flexibility (Lysons & Farrington, 2006). Cost reduction and efficiency improvement have frequently been reported as the major drivers of outsourcing. Smith and McKeen (2004, p.510) call them “outsourcing for operational efficiency” which is done with a clear objective of saving money through reductions in staff and other resources.2.1.2.2. Quality ImprovementQuality is the ability of product or service to consistently meet customer needs and expectations by giving value for money. The growth in outsourcing practice has been contributed by the firms need for diverse and high-quality services in order to survive and excel in the rapidly changing external environment (Kok & Richardson, 2003, p.54). Nevertheless, building strong outsourcing partnerships faces challenges as firms lack the know how to select their outsourcing vendors as well as poor management of outsourcing relationships (Kok & Richardson, 2003, p.55). Quality can be described as fitness for use. Quality in outsourcing contract exists when the contract serves its intended function and meets the objective of both parties. Outsourcing contract may be affected by organizational human and environmental factors. In order to build a satisfied relationship with service provider, firms need to equip themselves with the right knowledge and relationship management capabilities (Ren, Ngai, & Cho, 2010, p.454). In their study, Lee & Kim (1999) found that successful outsourcing contract quality is influenced by five factors which are: trust, business understanding, benefit and risk sharing, conflict and commitment, while Anderson & Narus (1990, p.43) found other factors such as communication, top management support and age of the relationship. Successful outsourcing contract enable firms to achieve organizational objective and build competitive advantage (Han, Lee, & Seo, 2008, p.32).2.1.2.3. Technology AdaptionOrganizations are choosing to outsource non-core service activities like human resource, Finance, Transport, I.T and Engineering services to both local and global service providers who are better placed with the experience and technical know-how in such areas. In any case outsourcing such functions is a challenging process. The process is driven by factors which are beyond cost reduction alone (Moeen, Somaya, & Mahoney, 2013, p.263). Other factors like service design, work management across different culture and business process redesign are important elements that must be considered in the management of service outsourcing. It is also the responsibility of the service provider to implement changes in the service industry as necessary brought about by changes in technology (Holcomb & Hitt, 2007, p.466). Similarly, when a firm does not have the required capacity to perform its non-core activities, outsourcing may be an option. Rising inflation rates make product prices to keep increasing calling for more capital and putting pressure on firms to further reduce their costs so that they can maintain short- and long-term survival (Moeen, Somaya, & Mahoney, 2013, p.264). Production activities are costly and calls for huge operation expenditure, hence have become major targets for outsourcing. Non-operational equipment leads to delays in delivery of products and services and this in turn causes poor organization performance which leads to customer dissatisfaction and loss of goodwill. For specialized (and custom built) equipment, the knowledge and skill to carry out the maintenance and spares needed for replacement need to be obtained from the original equipment manufacturers (OEM) (Holcomb & Hitt, 2007, p.457). Hence, customers must have a maintenance service contract with the OEM which results in a non-competitive market. If agents provide maintenance service instead of OEM the cost of switching prevents customers from changing their service agent, hence customers get “locked in” and are unable to do anything about it without a major financial consequence (Moeen et al., 2013, p.262).2.1.2.4. Risk ManagementThe objective of outsourcing should be to free up management and instill confidence in them to take up more risk in core areas of business which have more value addition. However, outsourcing of firm activities brings about critical risk related issues due to operational changes involving human resources, physical assets, technology and business processes, which lead to operational risk exposures (Irina et al., 2012, p.1069). Moreover, outsourcing brings about uncertainty because the new relationship between service provider and the firm represents an untested agreement. Also, it is difficult to justify whether the service provider will perform the task better than it was internally done (Lungescu, Pampa, & Salanta, 2011, p.271). Though outsourcing may come with different types of risks, they are all related to operation performance. This calls for serious risks evaluation before entering into an outsourcing arrangement of any business function (Irina et al., 2012, p.1070). Outsourcing brings about loss of control, loss of critical skills and knowledge, loss of intellectual property, loss of security, service quality may drop, and costs may increase as well as loss of innovative capability (Wayman, 2013, p.42). There should also be a continuous follow-up and monitoring of the service provider relationship as well as resolving disputes. The most important challenge is how to deal with the change in balance of power that turns in favor of the service provider (Weele, 2010). Due to the fact that parties in an outsourcing contract engage in a long-term relationship many things need to be taken into consideration. Some of the aspects are taken care of in the contract writing. According to Weele (2010), the risks associated with outsourcing contracts can be summed up as either, technical risks, commercial risks, contractual risks or performance risks.Several scholars (e.g. Bhattacharya et al., 2013; Njuguna, 2010; Kroes & Ghosh, 2010; Bustinza, Arias-Aranda, and Gutierrez-Gutierrez, 2010) have demonstrated that outsourcing positively influences organizational performance, which is discussed in the next section.

2.2. Organizational Performance

- According to Jenatabadi (2015, p.3) organizational performance can be generally defined as “a set of financial and nonfinancial indicators which offer information on the degree of achievement of objectives and results.” Cocca and Alberti (2010, p.192) suggest that organizational performance can be represented by the following dimensions: effectiveness, efficiency, quality, productivity, quality of life, profitability, innovation and learning. Effectiveness refers to the organization’s ability to accomplish its goals in right way while efficiency refers adequate use of resources to accomplish determined goals. Quality refers to the ability to effectively to meet or exceed customer expectations (Jiménez-Jiménez & Cegarra-Navarro, 2007, p.696); productivity is concerned with the ratio of output over input; quality of work life denotes the affective response of employees about their work and organization (Pavlov & Bournce, 2011, p.103); profitability refers to the excess revenues over costs while innovation refers to continuous improvement of product/service or processes (Rhee, Park, & Lee, 2010, p.66); and according to Argote (2011), learning has been defined as the ability of an organization to continuously create, retain and transfer knowledge within an organization. Key dimensions of organizational performance identified by other scholars include the ability to innovative (Liao & Wu, 2010; Rhee et al., 2010, p.1098); productivity (Field, 2011, p.274); employee satisfaction and amplified capability to gain, transfer and make use of new knowledge (García-Morales, Lloréns-Montes, & Verdú-Jover, 2008); competitive advantage (Hsu & Pereira, 2008, p.549), and enhancement of the organization’s reputation (Calantone, Cavusgil, and Zhao, 2002, p.516).For mining companies, organizational performance refers the firm’s effectiveness and efficiency in (i) setting standards, specifications, objectives, and goals and achieving them; (ii) ensuring satisfaction of all relevant stakeholders; and (iii) enforcing applicable policies and regulations.

2.3. Empirical Literature

- The relationship between outsourcing and organizational performance has been empirically investigated by a number of scholars. Based on the hypothesis that outsourcing is considered to be a value-added business, Hayes, Hunton, & Reck (2000) investigated how information systems (IS) outsourcing announcements impacted the market value of publicly traded contract-granting firms. What is interesting about this study is the finding that outsourcing announcements had a significant positive effect on small firms, whereas the effect on large firms was not significant. One theoretical explanation for this difference in market reaction was that due to higher information asymmetries surrounding smaller firms, the market reacted significantly more positive to value-added announcements than for larger firms. This explanation was consistent with Healy & Palepu (2001). However, it is important to note that the categorization of small firms in this study is based on the median size (of sales) of a sample of publicly traded firms, and not on any generally accepted definition of small businesses. Gilley and Rasheed (2000) examined the extent to which outsourcing of both peripheral and near-core tasks influences firms' financial and nonfinancial performance on a sample of 94 manufacturing firms in the U.S. The study did not find any significant direct effect of outsourcing on firm performance. However, an indirect effect on performance was found when using strategy (cost leadership vs. differentiation) and environmental dynamism as a moderator. One argument behind the moderating effect of strategy was that firms that pursue a cost leadership strategy are, by outsourcing, able to heighten their focus on their core competencies, and improve the quality of their nonstrategic activities. Using the same sample as in Gilley and Rasheed (2000), Gilley, Greer, & Rasheed (2004) analyzed the effect of outsourcing of human resource (HR) activities (payroll and training outsourcing) on firm performance. No effect was found on financial performance, but there was a small positive effect on firm innovation performance (R&D outlays, process innovation and product innovations) and stakeholder performance (employment growth & morale, customer and supplier relations). Based on the argument that human resource outsourcing would have a larger effect on smaller firms (due to transaction costs) the study also tested for a moderating effect of size. However, no support was found for the hypothesis that HR outsourcing would be contingent on the size of the organization – maybe due to a relatively small sample size. Jiang, Frazier, and Prater (2006) examined the impact of outsourcing on a firm's performance based on a sample of 51 publicly traded firms. Contrary to most previous studies on outsourcing effects, they used annual report data to measure performance and tested for changes in operating performances as a result from outsourcing decisions. They provided some evidence that outsourcing improved firm's cost‐efficiency (SG&A/sales and expenses/sales) but did not find any effect on firm’s productivity (sales/assets and asset productivity) or profitability (ROA and profit margin).Bolat and Yilmaz (2009) examined the relationship between the outsourcing process, and perceived organizational performance in 80 hotels in Turkey, and found support for the hypothesis that outsourcing have a positive effect on organizational performance (organizational effectiveness, productivity, profitability, quality, continuous improvement, quality of work life, and social responsibility levels). Bustinza, Arias-Aranda, and Gutierrez-Gutierrez (2010) studied 213 service firms in Spain, and concluded that there is a relationship between outsourcing decisions and company performance, which is articulated via the impact of outsourcing decisions on the firm's competitive capabilities. The study concluded that outsourcing encourages a development of resources that enables a sustainable competitive advantage. Kroes and Ghosh (2010) studied the degree of congruence (fit or alignment) between outsourcing drivers and competitive priorities, i.e., outsourcing decisions should be made in alignment with the competitive priorities of a firm. The study also evaluated the impact of congruence on both supply chain performance and business performance. The main findings were that outsourcing congruence across all five competitive priorities was positively and significantly related to supply chain performance.Using a qualitative research design, Bhattacharya et al. (2013) studied outsourcing in five organizations in Australia. Based on agency theory, the study analyzed how the receiver and the provider of outsourcing services perceived outsourcing from different angles, e.g., areas of convergence and divergence. The study found that the different parties often shared opinions regarding environmental uncertainty, conflict, information asymmetry and duration of contract, while differences were found regarding their view on degree of formality, opportunistic behavior, and mutual dependency of the parties involved, goal compatibility and switching costs.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

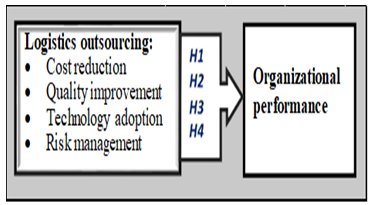

- This study seeks to expand the body of knowledge in the area logistics management by advancing and testing a model which postulates logistics outsourcing practices as determinants of organizational performance. The research model is presented in Figure 3.1.

| Figure 3.1. Research Model (adapted from Nzitunga, 2015) |

4. Methodology

- For this study, a quantitative approach was used. Measurable data were used to formulate facts and uncover patterns in research. This approach was selected because the study seeks to test a set of hypotheses and the literature underlines that this is an appropriate approach for a study designed to analyse the theory through narrow hypotheses proposition and data-gathering in order to prove or disprove these hypotheses (Leedy and Omrod, 2010). The questionnaire was constructed using the "research backwards" method. This means that the information sought was first determined and appropriate questions were developed to obtain this information. It was also imperative that the questions fitted the respondents' frame of reference. In this regard, it was necessary to ensure that respondents would have enough information or expertise to answer the questions truthfully. The population for this study comprised logistics department employees (including managers and supervisors) at Namdeb Diamond Corporation, one of the biggest diamond mining companies in Namibia. The company had a total of 105 logistics employees countrywide and a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to all of them via e-mail. The response rate was 95%.

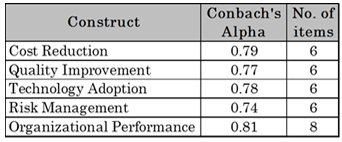

4.1. Validity and Reliability

- Face validity was ensured through the use of previously validated measures (Bhattacharya et al., 2013; Jenatabadi, 2015), which were refined where necessary. According to Waters (2011, p.38), face validity is established when the measurement items are conceptually consistent with the definition of a variable, and this type of validity has to be established prior to any theoretical testing. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency-reliability of the scale used. Cronbach’s alpha is “a measure of internal reliability for multi-item summated rating scales, and its values range between 0 and 1, where the higher the score, the more reliable the scale” (Waters, 2011, p.40). Satisfactory reliability is indicated by alpha score values of above 0.70 across all sections of the measuring instrument (Cooper and Schindler, 2011). The research instrument used for this study was reliable as shown in Table 4.1.

|

5. Findings and Discussion of Results

- Descriptive statistics were used “to describe the characteristics of the respondents” (Singleton and Straits, 2010, p.15). The Spearman correlation is used for ordinal data (Rebekić et al., 2015, p.49) and it was used in this study. Grounded on Abdi & Williams (2013) who recommend this method as the most suitable method to analyse multivariate relationships, Partial Least Squares regression analysis was used as inferential statistics. Another advantage of PLS regression is the fact that it does not necessitate a vast sample or data which is normally distributed (Abdi & Williams, 2013, p.568).

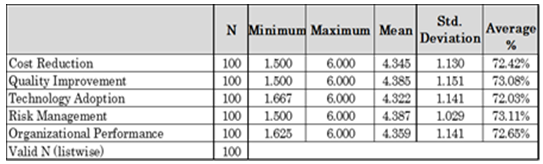

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

- For the descriptive statistics, the individual scores were totalled and an average score was calculated. Descriptive statistics of the composite variables are summarized in Table 5.1.

|

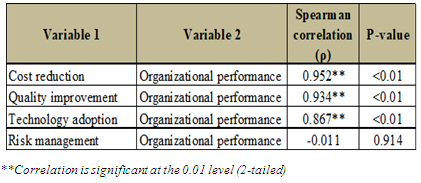

5.2. Correlations

- The relationships among the study variables were assessed using Spearman's correlation. Table 5.2 summarises the Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values for the different variables. The table shows statistically significant positive correlation between cost reduction and organizational performance (ρ = 0.952); quality improvement and organizational performance (ρ = 0.934); and technology adoption and organizational performance (ρ = 0.867). No statistically significant correlation was found between risk management and organizational performance.

|

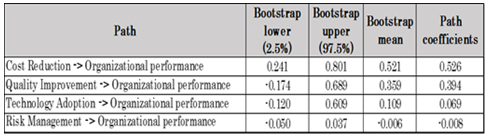

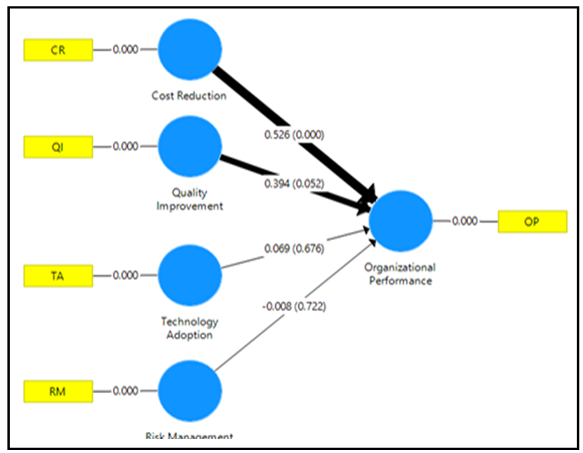

5.3. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression Analysis

|

| Figure 5.1. Path, strength and significance of the path coefficients assessed by PLS (n=100) |

5.4. Summary of Key Findings

5.4.1. Influence of Cost Reduction on Organizational Performance

- The first hypothesis – namely that cost reduction through logistics outsourcing positively affects organization performance in the Namibian mining industry – was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.526). This finding is consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Lysons and Farrington, 2006; Smith and McKeen, 2004). The managerial implications are that logistics outsourcing leads to reduced costs through the removal of unproductive assets; reduced investment in assets and redirection of internal resources to core company activities; and availability of more funds for other projects, which in turn results in enhanced organizational performance.

5.4.2. Influence of Quality Improvement on Organizational Performance

- For the second hypothesis – which suggested that quality improvement resulting from logistics outsourcing positively influences organizational performance in the Namibian mining industry – no statistically significant relationship was found in this regard by the PLS regression analysis. This is contrary to the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Ren et al., 2010; Han et al., 2008). This implies that for the Namibian mining industry, organizational performance is achieved irrespective of the level of logistics quality.

5.4.3. Influence of Technology Adoption on Organizational Performance

- Also, for the third hypothesis, namely that there is a positive relationship between technology adoption achieved from logistics outsourcing and organizational performance in the Namibian mining industry, no statistically significant relationship was found by the PLS regression analysis. This is also inconsistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Moeen et al., 2013; Holcomb & Hitt, 2007). This means that for the Namibian mining industry, organizational performance is achieved regardless of new technology adoption by the organization.

5.4.4. Influence of Risk Management on Organizational Performance

- Finally, with regards to the fourth hypothesis – which advanced that effective management of risks resulting from logistics outsourcing is likely to positively affect organizational performance in the Namibian mining industry – no statistically significant relationship was found by the PLS regression analysis. This also contrary to the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Irina et al., 2012; Wayman, 2013). Also, here, the managerial implications are that that for the Namibian mining industry, organizational performance is achieved regardless of whether the risks management practices are enhanced or not.

6. Summary

- Given the dearth of the literature in this field in the Namibian mining industry context, this study has contributed to supplementing the logistics management literature. Although the findings indicated satisfactory scores for the constructs of logistics outsourcing, as well as for organisational performance, there is always room for improvement. Sufficient evidence emerged from the study showing that it is imperative to ensure adequate outsourcing practices for improved organisational performance in the Namibian mining sector. These aspects are measurable, and therefore can be managed. Managers in the Namibian mining sector need to effectively address these issued and will require unrelenting support from researchers and other relevant stakeholders.The general research framework formulated for this study will guide further research, re-appraise current practices and provide basic guidelines for new policies. It is therefore significant for future researchers.

7. Conclusions

- The mining industry needs enormous logistical mechanisms and requires a careful management in this regard for effective organizational performance. The core business of a mining company is to extract minerals though they still need to procure materials, manage inventory and transports goods. All these other activities are non-core and can be outsourced so that the mining companies can focus on their core function which is extracting minerals.Given the findings of the study which revealed a positive influence of logistics outsourcing on organisational performance, steps that can be immediately taken to address the current situation can include but are not limited to the following: strategic planning incorporated into all stages and aspects of logistics management; ensuring that key personnel have the required and relevant academic or professional training in the aspects of logistics management; comprehension of contemporary logistics management concepts and principles by the top management of relevant departments; objectively measuring performance in terms of logistics management activities; and ensuring that there is appropriate equipment to effectively support contemporary logistics management policy implementation. This will only be effective if there is a strong desire and commitment on the part of managers in the Namibian mining sector work towards improvement in this regard.

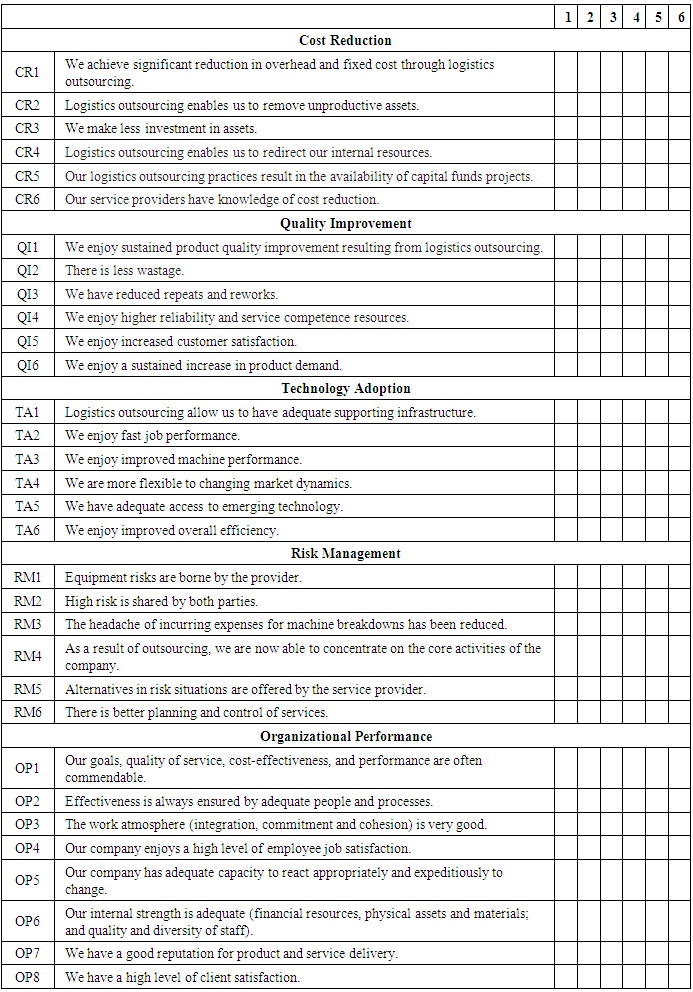

Appendix 1: Research Questionnaire

For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML