-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2018; 7(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20180701.01

The Application of Workplace Attrition in a Multiple-Claimant Gender Discrimination Case: The EEOC v. New Prime Trucking

Steve D. Mullins, Janis L. Prewitt

Breech School of Business Administration, Drury University, Springfield, MO, U.S.

Correspondence to: Janis L. Prewitt, Breech School of Business Administration, Drury University, Springfield, MO, U.S..

| Email: |  |

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) brought a class lawsuit against New Prime Trucking in September 2011. New Prime, one of the nation’s largest trucking companies, was charged with violating Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act for placing female applicants on a waiting list for the firm’s student driver training program. Male applicants, on the other hand, were provided with training in a timely manner. From the defendant’s perspective, the EEOC’s suit seemed like an expensive “catch-22” because the same-sex training policy had been adopted as a result of a previous lawsuit. In 2003, the EEOC filed a successful Title VII claim against the company for the sexual harassment of a female driver trainee by a male instructor. Although the same-sex training policy was intended to protect female trainees from harassment, the limited availability of female instructors caused a delay in female applicants’ access to training and employment with Prime. The EEOC sought an end to the discriminatory same-sex training policy in addition to back pay damages for the sixty-three affected claimants. One of the authors testified on behalf of the defendant and provided the court with an alternative estimate of back-pay damages to that provided by the EEOC expert’s damage estimate. The author’s use of firm-specific employment attrition data was central to his estimation of back-pay damages because of the unusually high rates of employee turnover in the long-haul trucking industry. The damage estimate provided by the EEOC’s economist did not consider attrition; consequently, the EEOC damage estimate was three times the amount provided by the author. This paper reviews the economic and legal perspectives on the issue, and then provides a specific application of the use of employment attrition in an important gender discrimination case involving multiple claimants who were represented by the EEOC in its case against New Prime, Inc.

Keywords: Attrition Rates in Trucking and damages

Cite this paper: Steve D. Mullins, Janis L. Prewitt, The Application of Workplace Attrition in a Multiple-Claimant Gender Discrimination Case: The EEOC v. New Prime Trucking, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20180701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is well established in the forensic economics literature that workplace attrition or job tenure should be considered when calculating the economic damages associated with lost pay resulting from wrongful failure to hire or employment termination.1 The need to adjust for these sources of employment uncertainty could hardly be more acute than they were in the multiple claimant gender discrimination case that the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission brought against New Prime Incorporated, one of the nation’s largest trucking companies, located in Springfield, Missouri. New Prime was charged in 2011 with violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act because the firm delayed or denied employment to female applicants for truck driving positions as a consequence of the trucking company’s same-sex training policy. Due to limited availability of female instructors, female applicants were placed on waiting lists to receive their training while male applicants were not. As a consequence, qualified male applicants promptly started the Prime Student Driver (PSD) program and, upon completion, began employment. On the other hand, female applicants would wait for up to six months to begin the PSD program. Most female applicants sought employment elsewhere after being informed of the lengthy delay. Prime had implemented the same-sex policy after the EEOC successfully sued the company in 2003 for a sexual harassment violation of Title VII. A female trainee was found to have been sexually harassed by a male instructor, and the plaintiff was awarded $80,000 in punitive damages and $5,000 in compensatory damages after a 10 day jury trial.2 Even though the training policy may have been established with good intentions, an EEOC attorney rejected the notion that this could be used as a defense in this case. Employers cannot avoid their responsibility to provide a workplace without sexual harassment simply by placing roadblocks in the path of qualified female applicants. Instead of proactively training and monitoring male truck drivers to avoid sexual harassment, the company put in place a discriminatory procedure that effectively deprived women of the opportunity to work as truck drivers.3The 2011 case was brought by the EEOC on behalf of women who claimed economic damages resulting from the defendant’s discriminatory failure to hire.4 Critical to the estimation of lost earnings in this case was the issue of employment attrition. The long-haul trucking industry is notorious for high rates of driver turnover and short job tenure, and the defendant in this case was no exception.5 The author used firm-specific driver attrition information in the preparation his damage estimate. The EEOC’s expert did not. Consequently, the damage estimates provided by the two economists differed by magnitudes. The EEOC’s economist estimated back-pay damages to be almost three times the author’s estimate. Most of the difference between the two damage calculations was due to the attrition issue. This paper will provide a case-specific illustration of the large impact that the adjustment for employment attrition had on the calculation of economic damages in a recent, important employment discrimination case. Labor discrimination attorneys and forensic economists will be surprised by the court’s decision in this case. While forensic economists agree that adjustments for high employee attrition are appropriate, the federal court judge ruled otherwise in EEOC v. New Prime, Inc.

2. An Economic Perspective on Use of Employment Attrition

- Forensic economists have long recognized the need to explicitly address the question of employment attrition/job turnover to calculate economic damages associated with lost earnings in wrongful termination cases. This section of the paper discusses three important contributions to the literature on this topic. In their 2003 article, White, Tanfa-Abboud, and Holt demonstrate the importance of considering workplace attrition in discrimination cases such as EEOC v New Prime Inc. “In discrimination cases…..the forensic economist must consider how long the plaintiff would have worked with that employer. When reliable data are available from the employer, the economist is able to examine the attrition rates or typical tenure of similarly situated employees.”6 The authors provide a case study to demonstrate an appropriate methodology. A hypothetical employee is assumed to be wrongfully terminated after seven years of employment. In the absence of the termination, the employee could have worked at the firm until retiring twenty-three years later. The employee was earning $57,000 annually prior to termination, and it is assumed she could mitigate her damages somewhat by obtaining alternative employment earning $45,000 per year. Hypothetical retention rates ranging from .99 for the first year of post-termination employment to .74 for the 23rd year are used to adjust the earnings that could have been expected if it were not for the wrongful termination. If no adjustment for attrition is made, the present value of twenty-three years of earnings losses is $393,144. Adjusting for attrition reduces the damages to $231,087 or about 60% of the unadjusted loss.7 While the use of hypothetical attrition rates can demonstrate the need to account for employee attrition, the forensic economist requires relevant estimates of attrition rates in order to apply White’s methodology in specific cases. Fortunately, other authors have obtained estimates of future employment probabilities using different sources of employment data. Two of these studies are considered here. The first used data obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the second used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NSLY). According to Trout, “[I]t is important to consider the likelihood that, but-for the termination, the terminated employee would have remained working for the defendant employer . . . .” A sample of 63,163 individuals obtained from the BLS Current Population Survey was used to estimate a logistic regression model that allowed him to determine the probability that an employee of a given age, income, education and employment duration would remain on the same job over time. Trout then demonstrated the large impact that adjustment for job retention could have in a hypothetical wrongful termination case.8Trout finds that a hypothetical forty year old employee with a high school education who earns $25,000 per year has 72% and 55% probabilities of being with the same employer at ages forty-four and forty-eight respectively. The impact of applying these probabilities to the calculation of economic damages is significant. This forty year old would experience employer-specific earnings of $416,000 over her expected work life if no accounting for probable employment changes is made. The estimate falls to $215,000 when employment probabilities are considered. If a ten year employment horizon were considered instead, the present value of future earnings is reduced by about one-third (from $216,000 to $160,000) when the earnings are adjusted for employment survival probability.9The BLS data used by Trout included occupational information for many of the respondents. This allowed him to estimate conditional probabilities of continued employment for different occupational categories as well. His occupation specific model demonstrated the need for forensic economists to consider occupational data (if available) because of the significant differences in employee attrition that are observed in different occupations. He finds, for example, that the hypothetical forty year-old manager would have a 65% probability of continued employment at age fifty, but that probability falls to 57% for a sales person.10 As will be shown later in the paper, the use of occupation-specific employee attrition had a huge impact on the estimation of economic damages in EEOC v New Prime, Inc. because of the unusually high rates of employee turnover in the long-haul trucking industry.11 In his 2013 article, Baum used estimates of employer-specific attrition obtained with data from NLSY to demonstrate the potential impact of adjustments for attrition applied to a hypothetical case. The NLSY tracked over 12,000 individuals from 1979 through 2010. Respondents were surveyed annually until 1994 after which the surveys were conducted every other year. Detailed employment status information including employer-specific data that was collected which allowed Baum to determine when employment spells with specific employers ended. The NLSY data was used to estimate a logit functional form that allowed him to calculate conditional probabilities that an employment spell with a particular employer would end in any year. He refers to these conditional probabilities of terminated employment as the hazard rate.12 The hazard rates are used to calculate annual employment survival rates which measure the cumulative probability of remaining with the same employer.13The implications of Baum’s work for the calculation of damages in wrongful termination or failure to hire cases are demonstrated using a hypothetical female high school graduate who was born in 1960. She is assumed to have been wrongfully terminated after five years of employment from an office and administrative support position paying $20 per hour or $40,000 per year. One year later she obtains reemployment earning $35,000 annually. She experiences three years of pre-trial losses and fifteen years of post-trial losses until an expected retirement age of sixty-seven. Using general income growth and discount rates (5% and 3% respectively), the present value of damages with no adjustments for the probability of continued employment is $182,000. However, the damages fall to $101,000 when employment attrition is considered. It is clear from Baum’s work that using employment survival probabilities obtained from the NLSY can have a substantial impact on a forensic economist’s estimate of the income losses experienced by the victim of employment discrimination.

3. An Application of Employment Attrition: EEOC v New Prime, Inc.

- The methodologies described in the previous section were used in a Title VII sex-discrimination case that was brought by the EEOC on behalf of multiple claimants against New Prime, Inc. The author served as an expert witness for the defendant New Prime and was asked to prepare an estimate of the economic damages caused by the employer’s use of a same-sex training policy that resulted in female applicants experiencing employment delays not experienced by male applicants. The EEOC filed its complaint against Prime in September of 2011 arguing that Prime violated Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.14 The EEOC complained that the “same-gender” driver-trainee policy resulted in over 700 female applicants experiencing training and employment delays. The number of claimants was ultimately reduced to a more manageable sixty-three. Two years later the court ruled that the training policy did result in prohibited sex discrimination because it prevented women from obtaining training and therefore employment with Prime.15 Having established liability, the court appointed a “special master” to determine the amount of back-pay damages due to the claimants.16 The court received testimony from four expert witnesses over the three-day hearing held in July 2015. Testimony documented the high rates of turnover among truck drivers in the industry in general as well as at Prime specifically. The court heard from two forensic economists who provided estimates of back-pay damages. Most of the hearing focused on the court’s attempt to reconcile the two widely divergent damage assessments. The remainder of this section will focus on the author’s use of firm-specific earnings and employment duration data in the estimation of damages and how his estimate differed substantially from that of the EEOC’s expert. The author’s use of employment survival probabilities (like those discussed in Baum’s work) and adjustments for the probability that the claimants would have successfully complete training necessary to obtain the Class A Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) were largely responsible for the large difference between the damage estimates.

4. Data and Methodology

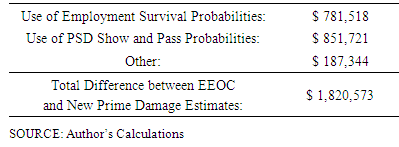

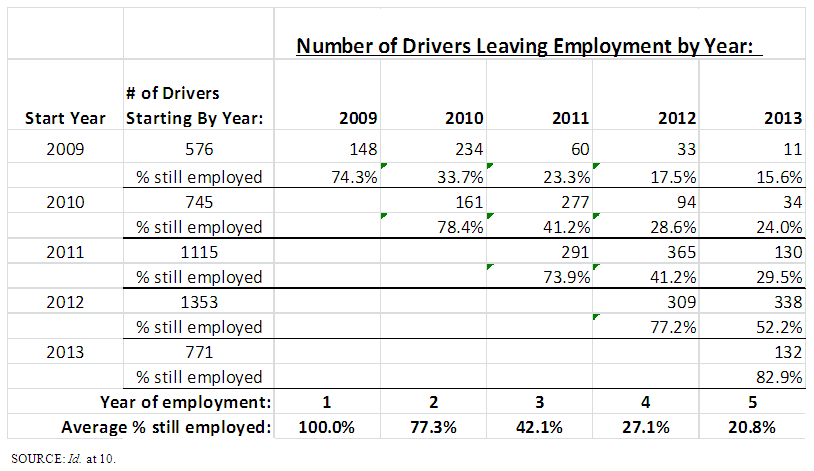

- The estimation of economic damages in this case required the author make critical assumptions to address specific questions regarding what each claimant would have earned at New Prime but-for discrimination. Prime provided both experts with an extensive dataset that documented the training, employment, driving, and compensation records for over 6000 applicants who entered the PSD program between 2009 and 2013. The data was used to address the following questions:1. What compensation (earnings plus benefits) would the claimants have earned if they drove continuously for New Prime? To answer this question is was assumed that had it not been for the discriminatory training policy, the claimants would have experienced the same compensation, on average, as did drivers that were employed at Prime over the same period. The claimants applied for employment at different points in time between 2009 and 2014 and would have experienced earnings that were specific to the point in time they would have begun driving. Consequently, the database was used to calculate average earnings for new drivers who started in each of five years. Table 1 shows the results of those calculations.

| Table 1. Cohort Average Driver Earnings and Benefits by Year and Seat Classification |

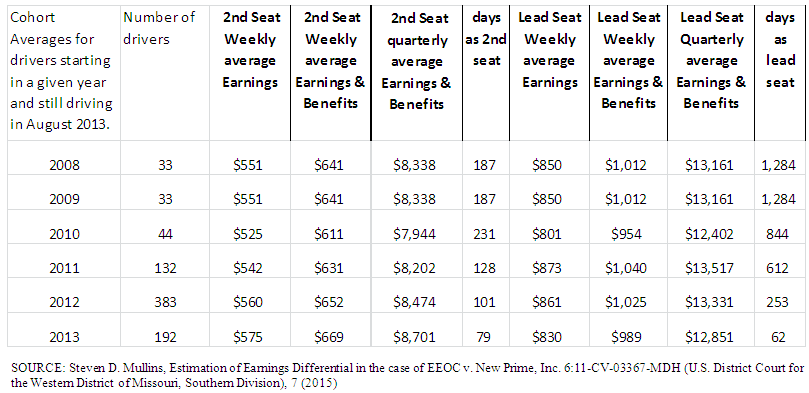

| Table 2. Average Employment Probability by Year of Employment |

| Table 3. Damage Calculations for “Toni Trucker” |

|

5. Summing up: The Impact of Adjusting for Attrition on the Damage Estimates

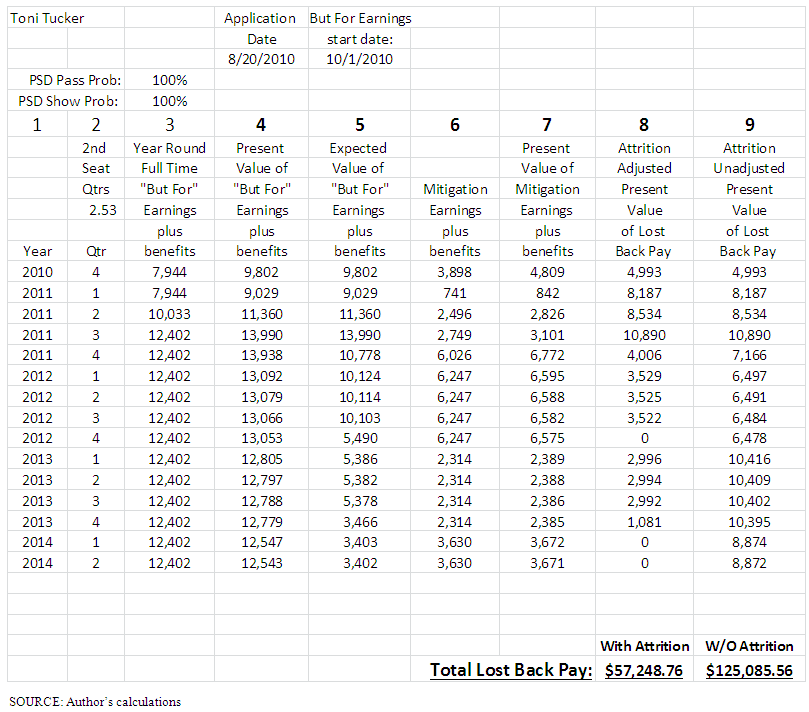

- The methodology described in the previous section was applied to each of the sixty-three claimants in the case with a resulting total for back pay damages of $976,889. The EEOC expert’s estimate was almost triple that number at $2,797,462.22 A large part of the $1.8 million difference between the damage estimates was due to the treatment of employment attrition. Table 4 shows how much the EEOC’s damage estimate for all claimants combined is reduced by the differences in methodology. The EEOC back pay damage estimate is reduced by $781,518 when the author’s employment survival probabilities are applied to the EEOC damage model, and damages are reduced by an additional $851,721 when but-for compensation is adjusted by the .55 probability that the thirty-eight claimants who never obtained their CDL would have attended and passed the PSD training program.23 The remaining $187,344 discrepancy is the result of the author’s use of the second seat-to-lead seat compensation progression and discounting to present value with lower interest rates.

6. Legal Arguments Regarding Attrition

- The EEOC and New Prime legal teams filed pre-hearing briefs with the special master providing legal precedents that each argued either rejected (EEOC) or supported (New Prime) the use of attrition. The EEOC cited EEOC v Dial Corp in which the Eighth Circuit Court ruled that an employer’s attrition rate need not be taken into account when determining back pay. The legal team for New Prime countered that this was a misrepresentation of the Dial case because the appellate court merely ruled that the lower court had not committed a reversible error by permitting expert testimony for the plaintiff that did not consider attrition. Nothing in the ruling suggested it was inappropriate for an expert to use attrition in a damages calculation.24 Counsel for New Prime also cited a number of cases to support their position that adjustments for employment attrition and short job tenure were appropriate. The court held that back pay should be limited to average job tenure in EEOC v Mike Smith Pontiac GMC, Inc. and if such a rule had been applied in New Prime, no claimant would have been allowed back pay for more than 400 days. A court “should apply the actual date that (the employee) stopped working, or the attrition factor” to calculate a back pay award according to the ruling in U.S. v. City of Warren, Mich., and in Green v. U.S. Steel and Dougherty v Barry the courts ruled that “the attrition factor” should be used because “[T]his ensures that damages are not paid for employees who would no longer be employed . . . .” in the absence of discrimination.25

7. The Special Master’s Ruling

- Judge Schaeperkoetter issued his ruling in EEOC v. New Prime in August of 2015. The judge took an a la carte approach by selecting pieces from each of the two damage models that he thought were appropriate. He chose the author’s estimation of but-for earnings and fringe benefits because they more accurately reflected the variation in earnings by seat class and used firm specific information about fringe benefits. He also used the author’s lower treasury yields over the higher IRS higher penalty rates for present value calculations.26 The author’s approach to establishing the beginning of the back-pay period was used because it differentiated between claimants that possessed or later obtained a CDL and those who did not. The EEOC expert made no such distinction when, in fact, applicants with a CDL would not have had to complete as lengthy of a training period. But on the most important difference between the two damage models, the court ruled in favor of the claimants by disallowing the adjustments for training and employment attrition experienced by thousands of New Prime applicants and drivers. This ruling was in spite of the strong presumption among forensic economists that using firm-specific data to account for attrition is appropriate. Judge Schaeperkoetter acknowledged that “[A]ttrition rates within the trucking industry are very high and volatile” but he rejected the author’s methodology on two grounds. First, he noted that the Baum and White articles that were referenced earlier in this paper and in court testimony made reference to “failure to promote or wrongful termination” cases. The articles did not specifically mention failure to hire cases such as EEOC v. New Prime and this, according to Schaeperkoetter, made the adjustment for attrition inappropriate because failure to promote and wrongful termination “claims are employee specific and do not have the element in this case of failure to hire.”27In addition, the judge argued that the claimant-specific mitigation employment and earnings evidence that he used to determine back-pay damage cutoff dates adequately accounted for high employment attrition in the trucking industry. His report stated that “The mitigation dates determined in this Report and Recommendation reflect an actual attrition rate . . . [that] stems directly from factors which cut-off or mitigate back pay eligibility (such as pregnancy, taking care of a loved one, schooling, career change, and the like) . . . .” He claimed this approach “seems to be a better, more reliable method of getting an attrition factor into the equation than Dr. Mullins’ assumptions that these 63 Claimants would across the board, follow the same historic trends of training and employment at Prime . . . [His] approach would paint all of the Claimants with the same ‘attrition’ brush.”28

8. Discussion

- The court’s two arguments for disallowing any attrition adjustment were puzzling. The special master did not elaborate regarding his distinction between failure to hire and wrongful termination discrimination cases, but from an economic perspective such a distinction is untenable. In both types of cases the court is faced with the task of estimating what the wronged employee (or applicant in this case) would have earned at the defendant firm if it were not for the discriminatory action. The point in time when the discriminatory act occurs—during the application process or after—is largely irrelevant to this problem. Firm-specific evidence obtained from a large population of New Prime drivers suggests that it was unrealistic to assume that all of the claimants were certain to have driven for Prime for their entire back-pay periods, but the court chose to dismiss that evidence. In addition, it makes little economic sense to use the post-discrimination labor force choices and experiences of each claimant to account for the firm-specific characteristic of high employment attrition. The erroneous consequences of the court’s approach can best be illustrated with an example. Consider the case of one plaintiff, let’s call her Ms. Driver, who applied at New Prime in late 2010 and would have started driving for the defendant firm in mid-January of 2011 if not for the discriminatory training policy. Ms. Driver’s case is especially relevant because it clearly demonstrates the need to consider employment attrition. The EEOC claimed Ms. Driver was eligible for twenty quarters of back pay, but the judge ruled otherwise based on her post-application employment experience. He cut off her back-pay eligibility in January 2013 based on the fact that, according to her deposition, she left her last trucking job in early 2013 after deciding she no longer wanted to be an over-the-road truck driver. Consequently, he ruled that Ms. Driver was entitled to 7.89 quarters of back pay.29 The judge’s cut-off decision was reasonable given Ms. Driver’s choice to no longer seek employment as a truck driver but it left unanswered the important question of what she would have likely earned at New Prime over that two year back-pay period. Ms. Driver was employed by six different trucking firms after applying at Prime. She drove as little as two months each for two firms and as long as eleven months for another. On average, her employment spells were about one and one-third quarter in length (four months and five days) before she moved on to the next trucking firm. It seems unreasonable for the court to assume she would have driven for the defendant for the entire 7.89 quarters when the firm’s employment data as well as Ms. Driver’s own employment experience suggest otherwise. The author’s employment survival probabilities could have been used to adjust her but-for earnings for the 77.3% likelihood that she would have still been driving for New Prime in the second year. Such an adjustment would have reduced the expected value of her but-for earnings by almost $14,000 and lowered her back-pay damage award to $35,000 from the $49,000 awarded by the court.With all due respect to the court, its ruling applies “the same attrition brush” to all claimants, albeit a brush of a more uniform color. Judge Schaeperkoetter assumed that all of the claimants had a 100% probability of working for the defendant firm regardless of whether or not they had demonstrated the capacity to obtain a CDL where the author’s approach differentiated between those claimants who obtained the CDL and those who did not. The ruling also assumed each claimant had the same 100% probability of working for the firm continuously over the entire back-pay period in spite of compelling evidence that the probability of continued employment fell sharply over time. At the end of the day, the judge’s refusal to consider employment attrition had a minor impact on the total damages awarded by the court because his decision to reconsider the back-pay cutoff date for each claimant resulted in many having their back-pay eligibility cut off at fewer than four quarters. As a consequence, only seven claimants were left with back-pay eligibility of sufficient duration (more than four quarters) so that the adjustment for employment attrition would reduce their damages. If Judge Schaeperkoetter had applied the author’s employment survival probabilities (from Table 2) to these seven claimants, their damages would have been reduced by $51,000. This adjustment would represent only 5% of the court’s total back-pay damage award of $1,085,000.30

9. Conclusions

- Forensic economists consistently make the case for applying employment attrition adjustments in wrongful termination cases. Economic logic dictates the methodology also applies to failure to hire cases such as EEOC v New Prime. The employment attrition observed at the defendant firm accounted for the large difference in the damage estimates provided by the two experts in this case. The back-pay damage estimate of almost $2.8 million brought to the court by the EEOC was almost three times the $977,000 estimate obtained by author, and most of the difference between the two was due to the author’s adjustment for employment and training attrition using data documenting the experiences of over 6000 applicants and drivers for the defendant firm.The judge in the damages hearing relied on most of the assumptions used by the author and awarded back-pay damages of $1,085,000 to the women who had been denied employment at New Prime as a consequence of a discriminatory training policy. The award was much closer to the author’s number than that of the EEOC’s expert, but to the surprise of the author, the judge disallowed any adjustment for training or employment attrition. The court did not provide a compelling rationale for the decision to disregard attrition, but the author suspects it was based on a desire to err on the side of claimants.31 Courts have consistently held that appropriate remedies for Title VII discrimination violations should make victims “whole” by providing “[c]omplete relief for a victim of discrimination . . . by placing the individual as near as possible in the situation he or she would have occupied if the wrong had not been committed.”32 This requires the court to “do its best to recreate the conditions and relationships that would have existed if the unlawful discrimination had not occurred.”33The “best” the court can do to “recreate” what would have transpired but-for unlawful discrimination is to explicitly acknowledge and build into the damage assessment the uncertainties involved. If one ignores high employment attrition in cases such as EEOC v. New Prime they substitute unlikely “conditions and relationships” for more plausible scenarios and require the defendant firm to pay an award that is in excess of what is needed to make the claimants whole. As this case demonstrates, the court may not always be receptive to the use of probabilities and expected values to deal with employment uncertainty, but it is the job of the defendant’s counsel - with the help of the forensic economist - to make the case.

Notes

- 1. Charles L. Baum, Employee Tenure and Economic Losses in Wrongful Termination Cases, 24 (1) J. Forensic Econ. 41, 41–66 (2013). See also Paul F. White et al., The Use of Attrition Rates for Economic Loss Calculations in Employment Discrimination Cases: A Hypothetical Case Study, 16 (2) J. Forensic Econ. 209, 209–23 (2003) and Robert Trout, Duration of Employment In Wrongful Termination Cases, 8 (2) J. Forensic Econ. 167, 167–77 (1995).2. Office of General Counsel 2003 Annual Report, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/litigation/reports/03annrpt/#IIC2. (last modified Jan. 5, 2005).3. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC Brings Class Lawsuit Against New Prime Trucking for Sex Discrimination, http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/9-22-11.cfm (Sep. 22, 2011).4. The original number of claimants was forty-six; however, additional women were added prior to the damages hearing in July of 2015 to bring the total number of women seeking compensation for lost back-pay to sixty-three.5. Multiple witnesses testified about high attrition rates in the trucking industry in depositions and at the 2015 trial. The EEOC did not contest this fact. 6. White et.al, The Use of Attrition Rates for Economic Loss Calculations in Employment Discrimination Cases: A Hypothetical Case Study, 209.7. These hypothetical results are likely to understate the importance of adjusting for attrition because the authors’ used hypothetical attrition rates that are much lower than would be expected based on estimates of employment attrition using Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, or the author’s firm specific data. 8. Robert Trout, Duration of Employment In Wrongful Termination Cases, 8 (2) J. Forensic Econ. 167 (1995) 9. Trout uses a 3% net discount rate to bring the $25,000 annual earnings loss to present value. He considers no actual earnings offsets. 10. Id. at 175. 11. The author used employment records for over 4000 truck drivers to determine that 42% of drivers were still driving for Prime two years after beginning their employment. The probability that an average driver would still be driving for the firm after six years was less than one-in-five. 12. Charles L. Baum, Employee Tenure and Economic Losses in Wrongful Termination Cases, 24 (1) J. Forensic Econ.41, 44 (2013). 13. Id. at 54. 14. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, supra note 3. 15. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Federal Judge Rules Prime Trucking's Same-Sex Training Policy Violates Federal Law, http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/8-18-14a.cfm 8-18-14 (Aug. 18, 2014).16. Attorney Jeff W. Schaeperkoetter was appointed by the court on March 19, 2015 to act as “Special Master” for the purpose of conducting the damages hearing in the U.S. Western District Court of Missouri, Southern Division. [Hereinafter referred to as Judge Schaeperkoetter] 17. Twenty five of the claimants either already had or later obtained their CDL prior to the damages hearing. No adjustment for the uncertainty of obtaining the needed certification was made for those women.18. The employment survival probabilities at the bottom of Table 2 are conservative. On average, 22.7% of new drivers left New Prime by the end of their first year of employment. This means that an accurate employment survival probability for the first year would be less than 100%. The author suggested to the legal team that 100% be used for the first year in order to give the claimants the benefit of the doubt. The lead attorney on the case agreed. He was fond of saying “Pigs are fed but hogs are taken to slaughter.” He did not want his attempt to reduce New Prime’s liability to appear unreasonably aggressive to the court. 19. No adjustment was made in Ms. Trucker’s case for the likelihood of her completing PSD training because she did ultimately obtain her CDL at a different driving school. If she had not done so the PSD show and pass probability of .55 would have been applied, further reducing the expected value of her but-for compensation. 20. Robert M. LaJeunesse, Revised Calculation of Economic Damages in the case of EEOC v. New Prime Inc. 6:11-CV-03367- MDH (Western District of Missouri, Southern Division 2015., May 14), 5 (2015).21. Prime’s legal team argued that the question of when a claimant should be “cut off” involved issues of law and fact that the economic experts were in no position to assess. The team provided the court with very detailed arguments regarding the number of quarters each claimant should be entitled to compensation. A full discussion of these details is far beyond the scope of this paper; however one interesting case does deserve mention. The EEOC wanted one claimant – let’s call her Ms. Short – to receive over $66,000 for 2.5 years of back pay, in spite of the fact that Ms. Short dropped out of another trucking firm’s driver training program after three days because, at 4’11” in height, she could not reach the pedals. Prime’s legal team argued she deserved no compensation. (Legal Team for the Defendant New Prime Inc., 2015, Appendix, pp. 61-62) The Special Master was apparently swayed by Prime’s argument and granted Ms. Short less than $500 in compensation. 22. These back-pay damages do not include additional damage compensation requested by the EEOC for “out of pocket expenses” that some of the claimants experienced. Nor do they include the EEOC’s request for a “tax penalty offset” to compensate some of the claimants for a possible income tax penalty they might experience as a result of receiving a large lump-sum damages payment which could place them into a higher income tax bracket. These amounts were relatively minor and are not addressed in this discussion. 23. While the focus of the paper has been on employment attrition, the requirement that applicants possess a CDL creates another source of “attrition” that also lower’s the probability of employment and therefore reduces the expected value of but-for compensation for those thirty-eight claimants who never achieved the CDL certification. The judge in the case explicitly recognized this attrition factor in his decision. He wrote that Prime’s damages expert “applied a three‐tiered attrition rate approach . . . .” based on the 75% probability that claimants would attend PSD, the 73.7% probability that they would pass, and “a third attrition rate based on the . . . 77.3% to 20.8%” probabilities of continued employment. See Jeff W. Schaeperkoetter, Report of the Special Master: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. New Prime Inc. 6:11‐CV‐03367‐MDH (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Missouri, Southern Division, August 27, 2015). 24. EEOC v. Dial Corp., 469 F.3d 735 (8th Cir. 2006) as referenced in the Prime legal team’s brief. (Legal Team for the Defendant New Prime Inc. 2015, 13)25. EEOC v. Mike Smith Pontiac GMC, Inc., 896 F.2d 524, 530 (11th Cir. 1990); Dougherty v. Barry, 869 F.2d 605 (D.C. Cir. 1989); Green v. U.S. Steel Corp., 640 F. Supp. 1521 (E.D. Pa. 1986) as referenced in the Prime legal team’s brief. (Legal Team for the Defendant New Prime Inc. 2015, 12)26. Judge Schaeperkoetter chose the treasury yields for discounting in spite of making an interesting observation from the bench that was repeated in his written ruling. “While it is a fair conclusion that the ‘average market Yield’ on U. S. Treasury securities is a manipulated interest rate that bears no relationship to real life, it is the appropriate rate.” See Schaeperkoetter; supra note 22, at 13. 27. Id. at 7.28. Id. at 6.29. Id. at 32–33. 30. The judge’s decision to ignore the impact of training attrition had a larger impact on the damage award because thirty-eight claimants never obtained their CDL. If it were not for discrimination they would have been required to attend and pass the PSD training program. The firm’s records indicated that about fifty-five percent of accepted applicants attended and successfully complete training. The application of this attrition factor would have reduced the expected value of but-for compensation and the damage award by $540,000. 31. During his testimony, the author was questioned by Judge Schaeperkoetter at some length about the attrition issue. The author explained that the EEOC expert’s damage model made the extremely unrealistic assumption that all sixty-three claimants would have remained employed at New Prime over their entire back-pay period, some as long as five years. It was much more reasonable, he argued, to assume that the claimants would have employment probabilities that reflected the experiences of New Prime drivers. The judge replied “I am afraid that if I use your attrition adjustment, some of the claimants are likely to be undercompensated.” 32. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 45 L.Ed.2d 280, 95 S.Ct. 2362,2373 (1975); EEOC v. Hungary, Inc. 108 F.3d 1569, 1580 (7th Cir. 1997)33. Quoted in U.S. v. City of Chicago, 853 F.2d.572,575 (7th Cir. 1988)

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML