-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2017; 6(1): 26-33

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20170601.03

Managing Supplier Relationship in a Typical Public Procurement Entity in Ghana: Outcome and Challenges

Samuel Bruce Rockson1, Ernest Owusu-Anane2, Kofi Akrasi Sey2

1School of Business, Cape Coast Technical University, Cape Coast, Ghana

2Department of Marketing, Procurement and Supply Chain Management, University College of Management Studies, Ghana

Correspondence to: Samuel Bruce Rockson, School of Business, Cape Coast Technical University, Cape Coast, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this paper is to determine ways of managing supplier relationships to improve public procurement performance whiles conforming to legal and procedural framework for public sector procurement. Supplier relationship management is one of the most important aspect of supply chain management. Most public sector institutions especially in developing economies however neglect this aspect in their procurement practices. The advent of the Public Procurement Act, 2003 (Act 663) in Ghana addresses so many procurement issues but does not address supplier relationship management issues to achieve a long term benefit for the organization that will bring a win-win approach for the benefit of the organization. Hence, this study was set using public tertiary educational institutions as a case study to determine how supplier relationships are managed vis-à-vis procurement regulations to achieve procurement performance. The main findings revealed that selected entity follows accepted strategies of supplier relationship management in extent literature in order to ensure value for money and improve procurement performance. However, the existing relationships has some accompanying challenges. We discuss the theoretical and managerial implications from these finding.

Keywords: Supplier Relationships, Public procurement, Procurement regulations, Procurement Act, public institution, Ghana

Cite this paper: Samuel Bruce Rockson, Ernest Owusu-Anane, Kofi Akrasi Sey, Managing Supplier Relationship in a Typical Public Procurement Entity in Ghana: Outcome and Challenges, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2017, pp. 26-33. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20170601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Supplier relationship management is one of the most important aspect of supply chain management. As purported, effective supplier relationship management and improving qualitative and quantitative levels of suppliers could be a competitive advantage of every company (Cusumano and Takeishi, 1991). In recent years, Supplier Relationship Management (SRM) has had a trend from traditional relationship (1960s) to logistic relationship (1980s) to partnership relationship (1990s) (Da Villa and Panizzolo, 1996). Wynstra et al. (2001) argued that suppliers are sources of ideas, technologies and savings in time and money. Ellram (1990) argues that when dealing with multiple suppliers, it is costly to coordinate the procurement process and to monitor the quality consistency of many different suppliers. Public procurement is one area that lags behind in terms of change especially in least developed nations. Most public sectors in least developed nations use a traditional procurement system which is purely based on adversarial relationships with many suppliers. Bid and Bash approach (Welch, 2003) is used in the tendering process which focuses on the lowest bid and arm’s length relationships with many suppliers. The contracts awarded to suppliers have a fixed expiry date, which means that their relationships end on the expiry date of the contract and a new tendering process will be triggered where potential suppliers are prompted to compete between them again (Christopher and Juttner, 2000).Erridge and Nondi (1994) found that ‘the extreme form of competitive bidding is, on the whole, incompatible with successful achievement of value for money. Erridge and Nondi (1994) further argues that extreme forms of competitive bidding are detrimental. These forms involve: rigid application of tendering procedures for low value items regardless of on-costs; too many suppliers; short-term contracts and the absence of cooperation from suppliers. The adversarial approach to supplier relationship management does not engender value for money, the core principle governing public procurement. The advent of the Public Procurement Act, 2003 (Act 663) addresses so many procurement issues but does not address supplier relationship management issues to achieve a long term benefit for the organization that will bring a win-win approach for the benefit of the organization. It is for this reason that this work is being undertaken to show the additional benefits that supplier relationship management will help improve and add more value to the aims of the Act 663 such as transparency, accountability and the ethical standards to ensure the judicious, economics and efficient use of state resources in public procurement. This will also ensure that public procurement is carried out in a fair, transparent and non-discriminatory manner.The challenges posed by the use of traditional procurement system in the Public sector procurement calls for a re-evaluation of the approach to come up with the best strategy for managing supplier relationships that beget value for money. Public procurement is an area that is rich for reforms and cost savings opportunities, increase product and service quality (NASPO, 2010). How can supplier relationship be managed in order to bring value for money in Public sector procurement? What benefits can the public sector gain from long term relationships with few suppliers? The study sought to answer the above research questions.It is against this backdrop that this study was set to identify different supplier relationship strategies which engender value for money in public procurement and the gains and improvement these relationship offer public sector procurement.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Supplier Relationship Management

- Supplier relationship management (SRM) is a complex business process that requires “resource allocation from the buyer and supplier to achieve a set of complex outputs”. These relationships are influenced by external environments and can be constrained by the parties’ strategies, goals and power mechanisms (Cousins et al., 2008).Supplier relationship management (SRM) is the discipline of strategically planning for, and managing, all interactions with third party organizations that supply goods and/or services to an organization in order to maximize the value of those interactions. In practice, SRM entails creating closer, more collaborative relationships with key suppliers in order to uncover and realize new value and reduce risk (Toroitich and Iravo, 2015).Research on supplier relationship management has been an area that has gained much concern in the area of supply chain management and has been reviewed by different authors with different definitions, concepts, variables, antecedents and outcomes. However, these studies focus on the performance impacts of a single party in the relationship.According to Leemputte (2015), successful supplier relationships require two-way information, recommendations, metrics and incentives. Lindgreen and Wynstra (2005) suggested that three widely differing supplier management models have emerged from both practice as well as academic research on the issue of how to optimally manage suppliers. Literature generally distinguishes between three basic purchasing strategies: Adversarial, competitive and collaborative. However, Bensaou (2000) suggests a hybrid of the competitive model and a partnership model as another supplier relationship strategy.One of the most pressing problems for enterprises is to ensure that their key suppliers are going in the same direction as themselves and form the right synergy in the long term. The issue there is that the journey of a relationship from an arm’s length to the core competence is marred with issues of diverse business agendas (Cox, 1996). On one hand, a business may want to keep its key supplier in business in order to secure the sources of supply in the long term. And on the other, it could just be about the short-term critical gain through seasonal supply of a bottleneck item. Whatever the case, the study by Wisner (2003) showed that key partnerships are the source of competitive advantage and can provide a platform for value differentiation. In this respect, it is more important than ever that a company and its suppliers align their strategy for success in the future.Therefore, the question of whether parties within a suppler relationship benefit from supply chain collaboration remains unanswered. This issue is particularly important since the expectation of positive returns for both parties is a prerequisite to gain their commitment to collaboration in the first place (Lambe et al., 2001).

2.2. Public Procurement

- Procurement is the process of acquiring goods, works and services, covering both acquisitions from third parties. It involves option appraisal and the critical ‘make or buy’ decision which may result in the provision of goods, works and services in appropriate circumstances (Public Procurement Act, 2003, Act 663). According to Azeem (2007), Public Procurement ‘is the acquisition of goods, works and services at the best possible total cost of ownership, in the right quantity and quality, at the right time, in the right place for the direct benefit or use of governments, corporations, or individuals, generally via a contract’. It can be said to be the purchase of goods, services and public works by government and public institutions. It has both an important effect on the economy and a direct impact on the daily lives of people as it is a way in which public policies are implemented.The Public Procurement Law, 2003 (Act 663) is a comprehensive legislation designed to eliminate the shortcomings and organizational weaknesses which were inherent in public procurement in Ghana. The government of Ghana, in consultation with its development partners had identified the public procurement system as an area that required urgent attention in view of the widespread perception of corrupt practices and inefficiencies, and to build trust in the procurement system. A study by the World Bank (2003) reported that about 50-70% of the national budget (after personal emoluments) is procurement related. Therefore an efficient public procurement system could ensure value for money in government expenditure, which is essential to a country facing enormous developmental challenges. To ensure sanity and value for money in the public procurement landscape, the government of Ghana in 1996 launched the Public Financial Management Reform Programme (PUFMARP). The purpose of the programme was to improve financial management in Ghana. PUFMARP identified weaknesses in the procurement system. Some of these weaknesses included: lack of comprehensive public procurement policy, lack of central body with technical expertise, absence of clearly defined roles and responsibilities for procurement entities, absence of comprehensive legal regime to safeguard public procurement, lack of rules and regulations to guide, direct, train and monitor public procurement. The programme also identified that there was no independent appeals process to address complaints from tenderers. These findings led to the establishment of the Public Procurement Oversight Group in 1999. The aim of this group was to steer the design of a comprehensive public procurement reform programme which led to the drafting of a public procurement bill in September 2002 that was passed into law on 31 December 2003.

2.3. Procurement Performance

- According to Hine (2004), the most challenging aspect of procurement practices is the modern management emphasis on measuring of supply chain performance. The chain is pictured as stretching from a firm‘s suppliers (and their suppliers, and their suppliers), through the buyers firm and onto customers (and their customers, and their customers). The I–Frame (Versendaal & Brinkkemper, 2004), a procurement improvement framework provides no less than twenty different methods of measuring procurement performance derived from several sources in the procurement and supply chain management literature. Van Weele (2001) identifies six methods of measuring procurement performance. Bailey and Farmer (1985), developed the 5 Rights of procurement as basis for measuring procurement practices performance. Also Humphreys et al (2004) developed a model much similar to Bailey and Farmer 5 Rights of Procurement based on procurement level of sophistication: strategic, tactical and operational. This study recommends a modified procurement performance model of Humphrey et al. (2004), procurement level of sophistication and Bailey and Farmer 5 Rights of Procurement.Performance management has become a key element in modern public sector governance and many developing countries have introduced it as a means to measure organizational and individual efficiency in order to ensure that public sector organizations meet the needs of the public (Ohemeng, 2009). Increasing the effectiveness, efficiency and transparency of public procurement systems has become an ongoing concern of governments and of the international development community (OECD, 2006). Measuring performance is a graceful way of calling an organization to account (Bruijn, 2007) and in public sector performance measurement; accountability is the central concern (Heinrich, 2007). Performance measurement is viewed as a warning, diagnosis and control system, that is used to keep track of economy (looking back), efficiency (current organizational process), effectiveness (output in the short term) and efficacy (output in the long term; also called outcome) (Teelken and Smeenk, 2003).

2.4. Relationship between Supplier Relationships and Public Procurement Performance

- There have been many studies on topics related to supplier relationship management (SRM), namely purchasing strategy, supplier selection and development, and collaboration with suppliers. However, these studies have not looked at the strategic management of supplier relationships in terms of the antecedents and outcomes of such engagements. These studies focus on the performance impacts of a single party in the relationship.Therefore, the question of whether parties within a suppler relationship benefit from supply chain collaboration remains unanswered. This issue is particularly important since the expectation of positive returns for both parties is a prerequisite to gain their commitment to collaboration in the first place (Lambe et al., 2001). Effectively managed strategic supplier relationships are reported to contribute to higher levels of customer service and reduced costs (Stank et al., 1999). Despite the importance of managing strategic supplier relationships, much of the previous research in the area has focused primarily on supplier selection (Sarkis and Talluri, 2002). Specific research that addresses the factors that influence effectively managed strategic supplier relationships has not been previously reported, although related work has been reported on business-to-business and supply chain buyer-seller relationships.Various scholars have suggested that supplier relationships can safeguard as a cost-effective form of governance between parties (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Humphreys et al., 2004), specifically informal ones such as goodwill trust (Gulati, 1995; Barney and Hansen, 1994) in addition to formal control and trust (Yang et al., 2011; Klein and Rai, 2009). The tangible benefits can be considerable as these informal safeguards are generally lower cost governance mechanisms than alternate forms that would involve complex legal contracts, extensive monitoring costs and security bonds (Zaheer et al., 1998) while intangible benefits can be considered as feeling and reacting as a team player (Sambasivan et al., 2011). The benefits from supplier relationships may also accrue as top-line revenue by virtue of faster new product development and more effective use of proprietary knowledge for value creation (Dyer, 1996; Dyer and Singh, 1998).

3. Methods

- In collecting data from the study’s sample, questionnaires were administered to the staffs of the procurement units of public tertiary institutions in Ghana. However, in order to ascertain broader scope of data gathered, interview sessions were conducted with key personnel of the units. Hence, both descriptive and inferential statistics tools were employed in analysing the data gathered. Even though the study sought to investigate public institutions in Ghana, it narrowed the scope to cover two public institution to make inference for related institutions. These were Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and Cape Coast Technical University (CCTU). Although there were many stakeholders for procurement of these institutions, the study primarily focused on just the staff of the procurement units who had requisite knowledge of their number and characteristics of suppliers, the procurement pattern of the institutions, the performance of the procurement units in order to do a better evaluation. However, to prevent instances of researcher bias in the process of data collection, the researchers used respondents who are knowledgeable and understood the details of the items used to measure the concepts and able to provide objective responses to the data collections tools. The respondent group identified comprised workforce who had a minimum of secondary education and have worked in the procurement unit or have experience in supplier relationship management or procurement in general for at least 2 years. The study population comprised of the following sections – Head section, Tendering section, Stores Account section, Evaluation section, Local Purchase Order (LPO) section, Stores A and B, Contract Management Section and Correspondent section, totaling to a number of seventy (70) respondents from two public entities in Ghana. Because of the relatively small population size of the two selected institutions, a sample was not taken, however a purposive sampling technique was convenient and appropriate for this study as purposive sampling is the most convenient method for the collection of members of the population that are near and readily available for research purposes (Welman & Kruger, 2005).

3.1. Measures and their Operationalization

- The items on the questionnaire were developed by basing on insights from extant literature regarding the subject matter. They were in different forms including 5-Point Likert scale questions ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree through 3=Neither Agree nor Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree on best strategies of managing supplier relationships that brings value for money in public procurement, benefits of supplier relationship management and challenges of supplier relationship management. In addition, there were other multiple-thought and dual-thought questions as the case may be with some open-ended questions as well. The open ended items were grouped based on the responses given by the respondents. The items were coded using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). Descriptive statistics indicating frequencies and percentages were used to present the results in figurative form. Some statistical tools were adopted by the researchers for analyzing the data for the study. The table or percentage approaches to the data analysis were chosen because they are convenient, reliable, simple and economical to deal with by the researcher and also user friendly. The table and diagrams will clearly display the result of the findings numerals that can be easily pictured and understood by any ordinary person who takes a look of the presentation.

4. Results

- Since the study was descriptive in nature, there was no need to measure validity and reliability of measures. Hence, the findings are collected from the field are reported descriptively. However, data from the completed questionnaire were checked for consistency. Collection of data for this study was centred on eight (8) sections within the two institutions that are directly involved in the Public Procurement Activities. These include Head Section, Tendering Section, Stores Account section, Evaluation Section, Local Purchase Order (L.P.O) section, Stores A and B, Contract Management Section and Correspondent (Professionals and mandatory staff obliged to undertake procurement activities). This was mainly done to gather information to find out how to manage supplier relationship to improve public procurement performance at the Procurement Office (KNUST and CCTU). It was however necessary to consider issues facing supplier relationship management.The main findings are presented in line with the scope and objectives of the study.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussions of Findings and Managerial Implications

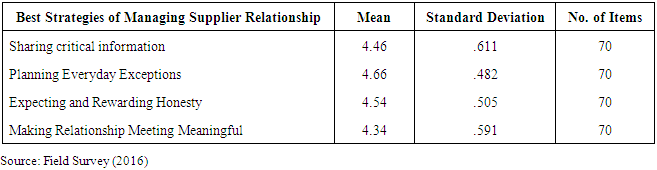

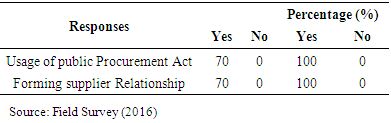

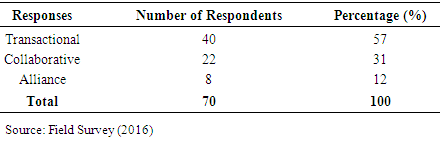

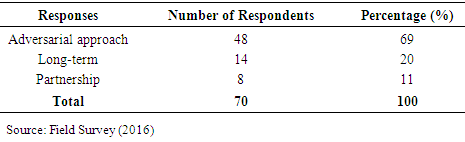

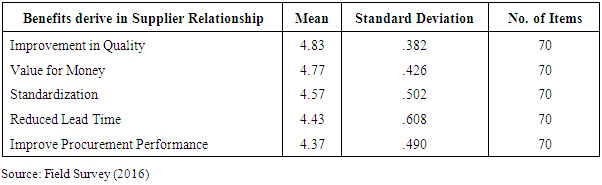

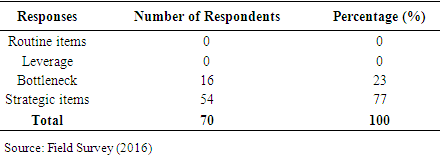

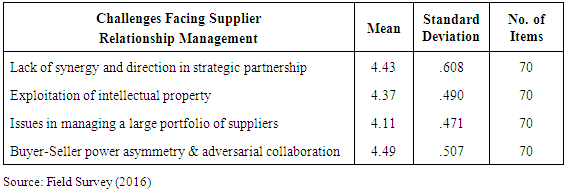

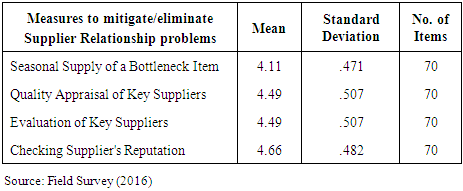

- It was observed from the findings that the selected entity strongly agrees with strategies of supplier relationship management as indicated by Leemputte (2015) in order to ensure value for money and to improve their performance. These strategies include sharing critical information; planning everyday expectations; expecting and rewarding honesty and making the relationship meaningful (Leemputte, 2015). In addition, KNUST and CCTU followed the Public Procurement Act 663 (Act 2003) in all their purchases but do so whiles having a good relationship with key suppliers to improve performance of the procurement unit of the institutions. It was also observed that the type of relationship that exists between the institution and its suppliers is a transactional relationship where goods from suppliers are exchanged for money and each time such products and/or goods are needed, the same procedure is used again. As such, this type of relationship is the most common and basic type of buyer-supplier relationship. Again, KNUST and CCTU as a procurement entities practice the Adversarial model in managing relationship with its supplier(s) in order to engender value for money in public sector procurement as per the objectives of the Public Procurement Act 663 and again improve procurement performance. The study also revealed that strategic items require long-term relationship with supplier(s) since it has great implementation for relationship according to Baily et al. (2005) and this is where the entity is most likely to find partnering approaches in which both sides will recognize and strive for the potential benefits. This implies that supplier relationship management within public institutions is not bad but there is more room for improvement as existing processes are coupled with some challenges. It is therefore necessary for management and key stakeholders to take measures to effectively manage their supplier relationships to gain mutual benefits which would eventually improve their performance.

6. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

- The study was concerned with managing supplier relationships in a typical public procurement entity in Ghana: outcome and challenges. It was also aimed at identifying the best strategy of managing supplier relationship that engenders value for money. The major limitation is that the study focused on a single public entity so the scope was narrow. Also, supplier relationship management could be different from the private sector which this study did not capture as well. One of the greatest challenges that the researchers encountered in this study related to access to and collection of secondary data due to extreme data gaps situations in the country. However, these limitations did not affect the validity and reliability of the study.In future, it is recommended the scope of the study should be broadened to cover several public institutions in the country. It is even possible for a comparative study of supplier relationship management to be conducted in order to make an effective generalization of findings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML