-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2016; 5(1): 32-38

doi:10.5923/j.logistics.20160501.05

Improving Local Linkages in the Supply Chain of Ghana’s Mining Industry: A Case of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited

Matida Kokui Owusu-Bio1, Daniel Obeng Donkor2, Abdul Samed Muntaka1

1Department of Information Systems and Decision Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

2Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Matida Kokui Owusu-Bio, Department of Information Systems and Decision Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

A critical issue in most gold producing economies in Africa is the existence of poverty in the midst of abundant gold. Linking the mining company’s supply chain demands and the community business activity could help the members take advantage of some of these activities. This calls for strengthening local linkages between the mining industry and the local community in order to improve the socio-economic development of the people. The sample size was two hundred and twenty people which comprised of workers of Newmont Ghana and the local community. The study revealed that; the degree of local sourcing in the mining industry in Ghana is very low. It was also found out that mining firms’ ability to source raw materials locally is challenged by certain factors such as mistrust and suppliers’ inability to supply the volumes required. The paper provides organizations and the government the need for local community participation in the supply chain of the gold mining industry. The paper also contributes to research by providing empirical evidence of the link between manufacturing organizations and their communities.

Keywords: Supply chain management, Strategic manufacturing, Mining industry, Operations management

Cite this paper: Matida Kokui Owusu-Bio, Daniel Obeng Donkor, Abdul Samed Muntaka, Improving Local Linkages in the Supply Chain of Ghana’s Mining Industry: A Case of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited, Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 32-38. doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20160501.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to Oshewolo (2010), Poverty holds sway in the midst of plenty. A critical issue with respect to Ghana and some other gold producing economies in Africa is the existence of poverty in the midst of abundant gold. Gold mining in fact, is held to create impoverishment and environmental hazard in mining communities with scar rather than benefit the country. Gold mining in Ghana appears to paint a positive picture of a long-established mining industry overcoming policy failures, upgrading its capabilities through significant investment and migrating into a new heightened phase of development (Bloch and Owusu, 2011). Academia and policy researchers have a negative notion of gold mining. This negative view then shapes a predominant public perception that, gold mining offers Ghana far less than it should in terms of public revenue, employment, skill development and spill over and local economic development. The mining sub-sector was the leading contributor to Ghana Revenue Authority’s collections in 2009. With about 520 million Ghana cedis which represented 21%. For Ghana to fully benefit from the gold mining sector, it would be prudent to link the mining sector to the rest of the national economy. The presence of effective local linkages is vital for the balanced growth of an economy. Thus, it is important that linkages that exist between the mining sector and the other sectors of the economy are strengthened so as to promote an all-round growth and development of the Ghanaian economy. This study adopted the case study approach with Newmont Ghana Gold Limited and Ahafo-Kenyasi community as the case. The population of this study was made up of senior managers and staff of Newmont Gold Ghana Limited, senior managers and staff of local suppliers of the mining firm and members of the Kenyasi community in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana. Primary and secondary data were used to address the research questions. Purposive sampling technique was used to identify some senior managers of Newmont Ghana whilst other respondents were randomly selected. A research population refers to a well-defined collection of individuals with similar or binding characteristics or traits (Castillo, 2009). To collect data from all the members of a population is considered impractical (Aaker 2010; Bryman & Bell 2011). A total of 220 people were used for this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supply Chain Management

- The idea of managing supply chains emerged in the 1980’s as a new integrative philosophy to manage the total flow of goods from suppliers to the ultimate user (Feller et al, 2006). It has since evolved to include a broader integration of business processes along the chain of supply. Wen et al. (2007) assert that competition has changed from being between individual enterprises to increasingly being between supply chains. As organizations form global alliances, it is imperative that they understand how SCM can be successfully applied (Halldorsson et al. 2008). Stadtler and Kilger (2005) define Supply Chain as; ‘a network of organizations that are involved through upstream and downstream linkages in the different processes and activities that produce value in the form of products and services in the hands of the ultimate customer’. For the purpose of this study, Supply Chain refers to the Product life-cycle processes comprising physical, information, financial, and knowledge flows whose purpose is to satisfy end-user requirements with physical products and services from multiple, and linked suppliers (Ayers, & Odegaard, 2008). The ultimate goal of SCM is to achieve greater profitability by adding value and creating efficiencies thereby, increasing customer satisfaction (Stock and Boyer 2009, p.703).

2.2. Linkages in Supply Chains and Challenges

- Linkages can be defined in different ways: quantitatively as inputs and outputs into the mining operation, or qualitatively in terms of the relationships between enterprises in the supply chain or as the exchange of ideas (UNECA, 2004). Choi et al, 2003 refer to supply chain linkages as explicit and/or implicit connections that a firm creates with critical entities of its supply chain in order to manage the flow and/or quality of inputs from suppliers into the firm and of outputs from the firm to customers. These linkages are created by implementing practices that include the involvement of suppliers and customers in product design activities, the investment in enterprise resource planning systems to allow information sharing across the supply chain, JIT II, Web-based system contracting, etc. (Choi et al, 2003)In order to strengthen the competitiveness of Supply Chain linkages, Balsmeier and Voisin (2002) recommend focusing efforts on improved communication, clarification of needs and expectations, elimination of problems and concerns, consistent performance, and the creation of competitive advantages. It is crucial for all members of the alliance to develop a standard for acceptable quality. When upstream manufacturers produce goods that are consistent, downstream purchasers are able to reduce time and costs of excess inspection and quality control of incoming products. Ideally, all levels of the supply chain will have real-time access to information concerning other firms. With increasing information technology, it becomes easier for firms to strengthen communication among themselves by providing accurate data in a timely manner. There are some challenges that may face strategic partnerships. Balsmeier and Voisin (2002) present six potential obstacles when forming supply chain linkages. These are; • Lack of shared vision • Culturally frozen beliefs• No shared sense of urgency• Lack of a champion• Lack of appropriate skills for the reinvented business • Lack of patronage by senior management.

3. Research Aims and Hypotheses

- Despite the work already done in relation to linkages in the supply chain of Ghana’s mining industry, there is still a need for a comprehensive study to improve local linkages in the supply chain of Ghana’s mining industry. This paper seeks to examine ways of improving local linkages in the supply chain of Ghana’s mining industry mining. It will go further to identify the level of local content in the supply chain of the Ghanaian gold mining industry. The paper identifies the various supply chain linkages that exists between Newmont Ghana Gold limited and the local community and also explores the possibility of linking local business activities to the mining industry’s supply chain. The last aim is to determine the challenges involved in improving the linkages between the supply chain activities of Newmont Ghana and the community.

3.1. Methodology

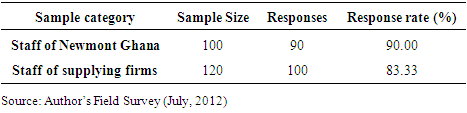

- This section discusses the research methods employed in the study. An exploratory study is a valuable means of “finding what is happening to seek new insights, to ask questions and to assess phenomena in a new light” (Saunders et al., 2009, p. 139) or to actually determine the nature of the phenomenon(Saunders et al., 2009, pp. 139-140). This study adopted an exploratory type of research design. The exploratory approach was an attempt to identify the local linkages that exist in Ghana’s gold mining supply chain and to suggest how these linkages can be improved.The sample size consists of 220. 90 out of the 190 respondents were made up of senior managers and staff of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited. The respondents from Newmont Ghana Gold Limited consist of five senior managers and 85 other staff. These 5 senior staff includes the community relations manager, the chief finance officer, human resource manager, procurement/supply chain manager and the production manager. The sampling technique used to identify these senior managers from the mining firm was purposive. The remaining 100 respondents comprises of 10 local supplying firms consisting of 10 respondents each. A simple random sampling technique was used to identify these respondents as well as the other staff of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited.Table 1 below shows the sample category, sample size, the number of responses received after questionnaires were administered and the various response rates.

|

4. Results

- This session consists of presentation and analysis of data collected from employees of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited and their suppliers. Out of 220 questionnaires administered, 190 questionnaires were filled and retrieved giving a response rate of 86.36%.

4.1. Local Sourcing of Raw Materials at Newmont Ghana

- Local sourcing of raw materials refers to a preference to buy raw materials produced in the community over those produced outside the local community. The researcher wanted to know whether Newmont Ghana sources any materials locally. This was indicated by 58.9% of the respondents.

4.1.1. Materials Sourced Locally

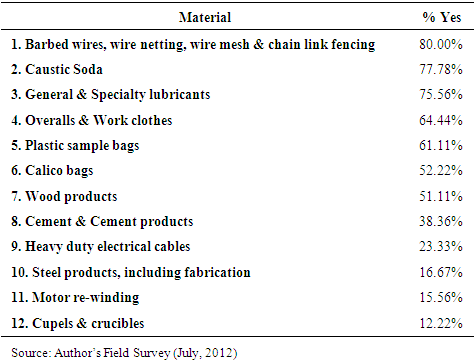

- Staff of Newmont Ghana were asked to indicate by choosing either ‘Yes’ or a ‘No’ against a list of materials that could be sourced locally. The percentage ‘yes’ is presented in table 2 below.

|

4.1.2. Activities of Newmont Provided by the Ahafo-Kenyasi Community

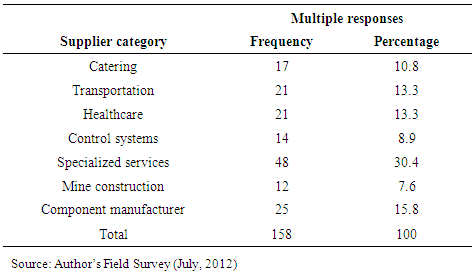

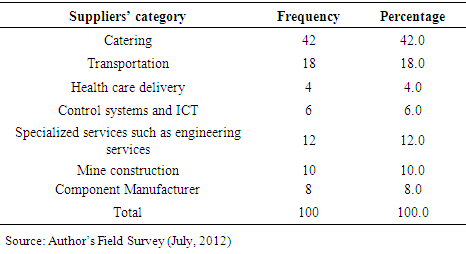

- Staff of Newmont were asked to tick against a list of activities on what their priorities would be if they were to increase supply from the local community. This is presented in table 3 below;

|

|

4.1.3. Level of Local Content in the Supply Chain of Newmont Ghana

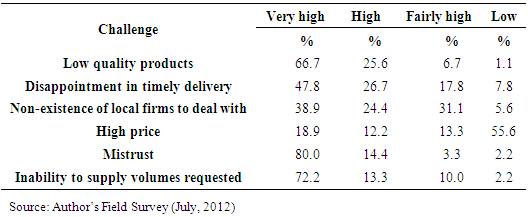

- This refers to the percentage of raw materials that were obtained locally in Newmont’s supply chain activities. Respondents were asked to indicate the percentage of local raw materials in their finished products. This is presented in figure 1 below;

| Figure 1. Percentage of raw materials sourced locally |

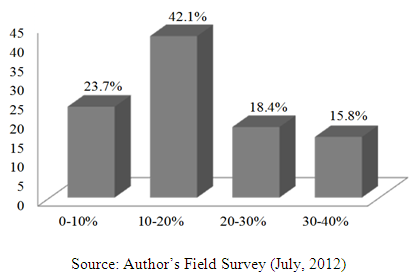

4.2. Various Linkages in Newmont’s Supply Chain

- Currently, Newmont has approximately 516 suppliers which are categorized into four groups or tiers. These four tiers are shown in figure 2 below;

| Figure 2. Newmont Ghana and its supply chain (Author’s Construct, 2012) |

4.2.1. Backward Linkages

- Backward linkages in Newmont’s supply chain arise out of activities established supplying inputs to the production of a commodity. This is a crucial linkage element for ongoing industrialization and development. To use Newmont’s categorization, this includes participation from five types of localized company: Local-local, Ghanaian-owned, Ghanaian-participating, Ghanaian-registered, and International companies.

4.2.2. Forward Linkages

- Forward linkages in mining supply chain arise from the processing prior to export of gold. Within industrial-scale gold mining in Ghana, gold ores are mined and the metal extracted at the mines themselves to the stage of semi-pure ore bars, which are then sold and transported for further refining. There is little actual refining of gold in Ghana, especially for local suppliers. Similarly, there is also little evidence of jewelry or other industrial production on any scale in Ghana though in principle, the possibility exists for such downstream linkages, especially in jewelry making. The lack of these linkages is mainly from increasing prices of Gold on the world market and lack of innovative technology in jewelry production (less efficient traditional methods and technology are still been used) Also there is very low local demand for gold jewelry and accessories compounded by cheaper jewelry imports from Asia and the Middle East.

4.2.3. Fiscal Linkages

- The development and utilization of fiscal linkages by the state, usually in the form of tax receipts coincides with gold production in the country. However it is undisputed that gold mining in Ghana has over a long time period contributed in major fashion to the government’s revenues in the form of royalties, corporate taxes, payroll taxes, a short-lived reconstruction levy and various other minor instruments, and hence contributed to the country’s fiscal health and stability (Aryee, 2001; Akabzaa, 2009).The mining industry’s contribution to government revenue – and hence of the fiscal linkage – over the past decade, has risen from a level of about 14% of total tax revenue to about 20%.

4.3. Challenges of Linking the Community to the Supply Chain of Newmont Ghana

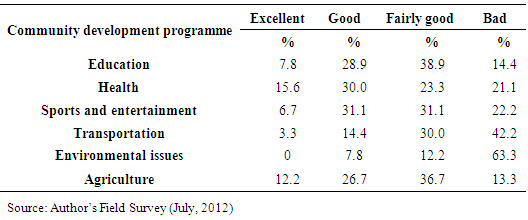

- The respondents were asked to identify why it is difficult to link the community to Newmont Ghana supply chain activities. Mistrust among local suppliers among others was seen as the greatest challenge. Table 5 below illustrates the responses on linkages challenges.

|

|

5. Conclusions

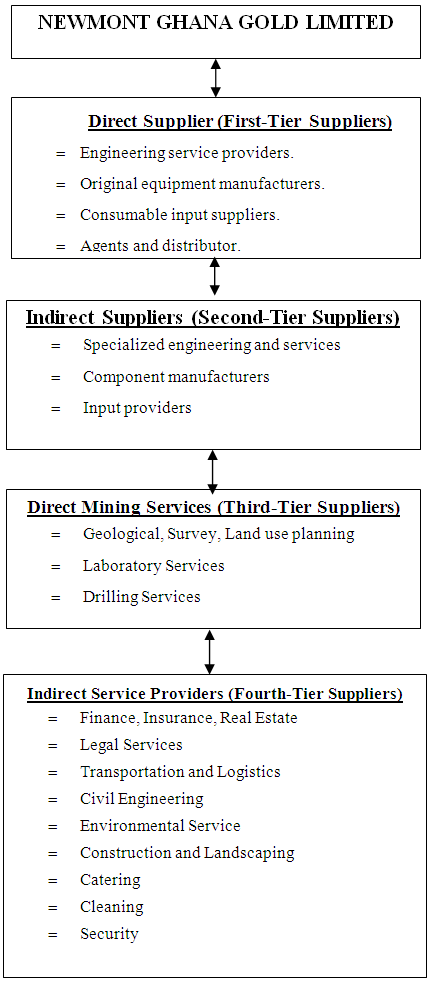

- The purpose of this study was to examine ways of improving local linkages in the supply chain of Ghana’s mining industry using Newmont Ghana as a case study. The study revealed that, increasing local participation in the supply chain activities will be the best way to improve socio-economic development. From the analysis, it was found that the degree of local sourcing in the mining industry is very low. Thus, only a small percentage of raw materials are sourced locally. However, materials such as barbed wires, wire netting and welded mesh can be sourced locally. Also, only a small percentage of the workforce in the mining sector can be indigenes. As such, there seems to be a disconnection between what the mining companies are demanding from local suppliers and what suppliers are producing.Respondents indicated that, in order to improve upon the linkages and enhance local development, Newmont Ghana can give a quota of non-skilled staff to the indigenes and also community development projects should be awarded to the local community members. In short, it has been found from the study that, the mining firm cannot find adequate skilled labour from the community. This is as a result of the low level of education among indigenes. Although the mining sector is performing well in terms of certain community development programs such as health and agriculture, the sector needs to improve upon its environmental development programs. Also, the mining firms’ ability to source raw materials locally is challenged by certain factors such as mistrust. Finally, there appear to be a disconnection between what the mining company demands and what local suppliers are producing.As a result of the strong global demand for gold, mining exploration and subsequent production in Ghana is now poised for further growth. Increasing local participation will be the best way to improve socio-economic development. It is against this backdrop that bridging the gap by establishing deeper forms of cooperation is vital for socio-economic development.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML