-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Logistics Management

2012; 1(3): 18-23

doi: 10.5923/j.logistics.20120103.02

Overview on Supplier Selection of Goods versus 3PL Selection

1LGIPM, ENIM-Lorraine University, route d’Ars Laquenexy, CS 65820, 57078 Metz Cedex 3, France

2CERIFIGE, UFR ESM-IAE, Lorraine University, rue Augustin Fresnel, BP 15100, 57073 Metz Cedex 3, France

Correspondence to: Aicha Aguezzoul , LGIPM, ENIM-Lorraine University, route d’Ars Laquenexy, CS 65820, 57078 Metz Cedex 3, France.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Supplier selection is a strategic purchasing decision that affects the total performance of every company. That decision is a multicriteria problem and a complex process that requires the use of several often conflicting criteria. This paper presents a comparative study between the selection of suppliers of goods and that of suppliers of logistics services in terms of criteria and methods. It shows that some criteria are more specific to logistics services than products and vice versa. Moreover, the importance order of these criteria in both cases is not the same. In terms of methods, they can be classified in seven categories namely: linear weighting models, statistical/probabilistic approaches, artificial intelligence, mathematical programming, methods based on costs, outranking methods, and hybrid approaches.

Keywords: Supplier Selection, Logistics Services, Multi-criteria, Decision Making

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In today’s business world, a company can not be competitive without working in close collaboration with external partners. The concept of Supply Chain Management (SCM) emerged in this direction and seeks to optimally manage the physical and information flows exchanged between all actors in a supply chain, namely: suppliers of goods, Third-Party Logistics providers (3PL), customers, wholesalers, etc. Among these actors, there are suppliers of goods and 3PL. On one hand, the supplier selection of goods is one of the most critical activities in purchasing or procurement process that commits significant resources, ranging from 40% to 80% of total product cost[1]. On the other hand, the logistics services such as transportation and warehousing account a large part of the total logistic cost.Note that there are main differences between the purchasing of goods and the purchasing of services. Services are intangible and heterogeneous in the same manner as goods. Moreover, whereas the production and consumption of goods can be separated, those of services usually occur simultaneously. Finally, goods can be stocked, while services have to be delivered at the moment they are needed.However, working with the suppliers of goods/services involves the selection of those that can meet the needs of their customers and with whom the company can maintain long-term relationship. This selection is a multicriteria problem and a complex process that requires various quantitative and qualitative criteria such as price, quality, delivery, reputation, etc. Some criteria are developed with specific customers needs while others are common for all circumstances. To solve this problem, several methods are proposed in the literature related to supplier selection of goods and only few in the case of 3PL selection. In the case of supplier selection of goods, our analysis will be referred to the studies done by many authors[2-6]. In the case of 3PL selection, we refer to the only studies to our knowledge that have addressed an overview on this issue, which are those of Aguezzoul[7-9]. The aim of this paper is to present a study on supplier selection of goods versus 3PL selection. It is thus organized as follows: 3PL characteristics are presented in the next section. Section 3 discusses the criteria used for selecting suppliers of goods and 3PL. In section 4, different methods for evaluating the performance of suppliers of goods and 3PL are described. Conclusions and future research are given in the final section.

2. Characteristics of 3PL

- Much has been written in recent years about outsourcing logistics activities and this outsourcing can be defined as an activity entrusted to a 3PL instead of being achieved internally[10]. It also involves activities carried out by a 3PL on behalf of a shipper and consisting of at least management and execution of transportation and warehousing. In addition, other activities can be included such as inventory management, information related activities, such as tracking and tracing, value added activities, such as secondary assembly and installation of products, or even SCM[11]. The 3PL can perform the logistics functions of their customer either completely or only in part[12-13] and currently, they have their own warehouses, transport fleets and their credits are often deployed throughout the world. Most 3PL have specialized their services through differentiation, with the scope of services encompassing a variety of options ranging from limited services to broad activities covering the supply chain. An overview of supplied logistics activities is shown in table 1[14].

3. Selection Criteria

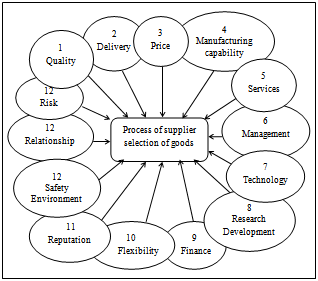

- As mentioned previously, the supplier selection is a multi-criteria problem and hence a complex process because it involves various conflicting criteria. In the case of supplier selection of goods, the earliest writings are those of Dickson[15] which, from a survey of 274 Canadian and US firms members of the National Association of Purchasing Managers (NAPM), have identified 23 criteria used by businesses in the 60 to select their suppliers. Moreover, Weber et al.[16] reviewed, annotated, and classified 74 articles appeared during 1966-1990 period. They showed that the criteria mentioned by Dickson are still studied in most articles. In their analysis of more than 110 papers published during 1990-2001 period, Cheraghi et al.[17] have identified 30 criteria and showed that some criteria mentioned by Dickson and Weber are no longer used.Table 2 bellow gives the relative importance of each criterion from 1996 to 2001.

|

| Figure 1. Criteria for supplier selection of goods (2010) |

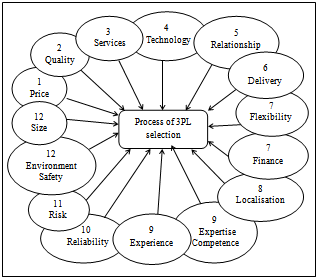

| Figure 2. Criteria for 3PL selection (2010) |

4. Selection Methods

- The main methods for supplier selection of goods have been classified according to seven categories: linear weighting models, statistical/probabilistic approaches, artificial intelligence, mathematical programming, methods based on costs, outranking methods, and hybrid approaches.

4.1. Linear Weighting Models

- These models place a weight on each criterion and provide a total score for each supplier by summing up the supplier performance on the criteria multiplied by their associated weights. The main methods in this category are: Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Analytic Network Process (ANP), TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution), and SMART (Simple Multi-Attribute Rating Technique):▪ AHP is a process that involves structuring multiple choice criteria into a hierarchy, assessing the relative importance of these criteria, comparing suppliers for each criterion, and determining an overall ranking of the suppliers.▪ ANP approach, which is a more general form of AHP, represents interdependencies of the higher-level elements of the hierarchy, from lower-level elements and also of the elements within their own level.▪ TOPSIS method is based on the idea, that the chosen supplier should have the shortest distance from the positive ideal solution and on the other side the farthest distance of the negative ideal solution.▪ SMART uses the simple additive weight method to obtain total values for individual suppliers, helping to rank them according to order of preference.

4.2. Statistical/Probabilistic Approaches

- Most statistical methods used are mean and correlation and that refer to the data gathered from the empirical studies. Other statistical/probabilistic methods cited in literature are: payoff matrix, vendor profile analysis, fuzzy set theory, factor analysis, interpretive structural modelling (ISM), cluster analysis, and binary logit:▪ Payoff matrix, defines several scenarios of future behaviour of suppliers. In each scenario, a note is likely associated overlooked criteria. The selected vendor is the one that has a stable note under different scenarios.▪ Vendor profile analysis assumes a probabilistic function for each supplier with respect to each criterion. By simulation, the behaviour of suppliers is estimated. ▪ Fuzzy set theory allows to model uncertainty and imprecision of weights assigned to criteria.▪ Factor analysis is a statistical approach that analyzes interrelationships among a large number of variables (criteria) and explains these variables in terms of their common underlying dimensions (factors).▪ ISM is an analytical method for determining the relationships between criteria and their levels of importance in order to classify them en sectors. It allows the identification of dependent criteria and independent criteria.▪ Cluster analysis is a statistical method to group suppliers in a number of clusters. The differences between the suppliers of the same cluster should be minimal and those between suppliers of different clusters must be significant.▪ Binary logit model or logistic regression model is used when the dependent variable is not continuous but instead has only two possible outcomes, 1 or 0. For example, the dependent variable is the transaction dummy. If a transaction between a buyer and a supplier occurs, the value of this variable will be 1; otherwise, it will be 0.

4.3. Artificial Intelligence

- Artificial intelligence aims to integrate qualitative factors and human expertise in the selection process. The three main systems that characterise the artificial intelligence are: expert systems, CBR/RBR (case-based reasoning/rule-based reasoning), and ANN (artificial neural networks):▪ Expert systems are used to represent knowledge and expertise which professionals hold on the suppliers as well as the information collected from the literature on the various stages of their selection such as the formulation of criteria.▪ CBR/RBR is a technique for solving the present problem through adjusting by way of similar past problems. It’s used to select the best supplier based on the previous successful and relevant cases.▪ ANN represents an information-processing technique, developed to simulate the functions of a human brain. It can deal with the complexity and conflicts existing in selecting supplier through its two characteristics: learning and recall. Learning is the process of adjusting a network model to produce the desired output. Recall is the process of providing an output for a given input in accordance within the trained model.

4.4. Mathematical Programming

- Mathematical programming models generally consist of one or more objective functions to be optimized with or not a set of constraints faced by the decision-maker. The main methods in this category are: linear/nonlinear programming, mixed integer linear/nonlinear programming, goal programming, and multi-objective programming.Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is also used in this category as a mathematical programming technique for assessing the comparative efficiencies of decision-making units where the presence of multiple inputs and outputs makes comparison difficult.

4.5. Methods Based on Costs

- These techniques are quite complex and require the identification and calculation of costs generated by the various activities involved in the purchase transaction such as the quality control of products, transportation, administrative costs, etc. The models classified in this category are: Activity Based Costing (ABC), and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO):▪ ABC is a costing model that identifies activities in an organization and assigns the cost of each activity resource to all products and services according to the actual consumption by each. It's used to select suppliers who minimize the total additional costs associated with the purchase decision.▪ TCO is a method of calculating both the direct and the hidden costs of an equipment purchase. It includes the purchase price and all the underlying operational costs such as quality, inspection, delivery, etc.

4.6. Outranking Methods

- Outranking methods serve as one alternative for approaching complex choice problems with multiple criteria and multiple participants. The outranking indicates the degree of dominance of one alternative over another and provides the (partial) preference ranking of the alternatives. Most outranking methods build a preference relation between alternatives using the concordance / non-discordance principle. This principle leads to declaring that an alternative is “superior” to another, if the coalition of attributes supporting this proposition is “sufficiently important” (concordance condition) and if there is no attribute that “strongly rejects” it (non-discordance condition). The most used is ELECTRE (ELimination and Choice Expressing Reality) method.

4.7. Integrated Approaches

- Methods integrating two or more of different methods mentioned above are also discussed in the literature. Table III below indicates the number of articles that proposed each of the different methods mentioned previously in the case of supplier selection of goods vs 3PL selection. This number includes the methods used individually or combined with others.Of all the methods proposed in the case of supplier selection, this table shows that some methods are not yet used in the case of 3PL selection, especially SMART method, statistical/probabilistic approaches (fuzzy set theory, factor analysis, payoff matrix, and vendor profile analysis), and ABC method. Moreover, some methods such as AHP, mathematical programming, and DEA are widely proposed in the case of supplier selection of goods

5. Conclusions

- Based on an analysis of studies recently published on supplier selection (goods, logistics services), this paper allows drawing the following conclusions:Firstly, supplier selection decision is complex and requires the use of several often conflicting criteria. Some criteria are more specific to services than products and vice versa. Secondly, few methods of 3PL selection are published in comparison with those used in the case of supplier selection of goods. These methods can be classified in seven categories namely: linear weighting models, statistical/probabilistic approaches, artificial intelligence, mathematical programming, methods based on costs, outranking methods, and hybrid approaches. Thirdly, and as mentioned in[7-9], the main studies on 3PL selection are empirically and mean/correlation remains the most widely used method. Moreover, little attention is given to the application of statistical/probabilistic models such as fuzzy set theory, factor analysis, vendor profile analysis, and payoff matrix; and models based on total cost such as ABC. For mathematical models, they are mainly used in modelling, optimization, planning and evaluation of the integrated logistics network for 3PL.This study will provide research opportunities on the implementation of such models, especially those that take into account criteria related to the environment issues in the current context of sustainable development.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

| [1] | A. Aguezzoul, and P. Ladet, “A nonlinear multiobjective approach for the supplier selection, integrating transportation policies”, Journal of Modelling in Management, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 157-169, 2007. |

| [2] | L. De Boer, E. Labro, and P. Morlacchi, “A review of methods supporting supplier selection”, European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, vol. 7, pp. 75-89, 2001. |

| [3] | A. Aguezzoul, and P. Ladet, “Sélection et évaluation des fournisseurs : Critères et méthodes”, Revue Française de Gestion Industrielle, vol. 2, pp. 5-27, 2006. |

| [4] | N. Aissaoui, M. Haouari, and E. Hassini, “Supplier selection and order lot sizing modelling: A review”, Computers & Operations Research, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 3516-3540, 2007. |

| [5] | C. Wu, and D. Barnes, “A literature review of decision-making models and approaches for partner selection in agile supply chains”, Journal of Purchasing & Supply Chain, vol. 17, pp. 256-274, 2011. |

| [6] | W. Ho, X. Xu, and P. K. Dey, “Multi-criteria decision making approaches for supplier evaluation and selection: A literature review”, European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 202, pp. 16-24, 2010. |

| [7] | A. Aguezzoul, “A preliminary analysis on third-party logistics selection”, in Proceeding of the 7th International Research Conference on Logistics and Supply Chain Management Research (RIRL’2008), 2008.. |

| [8] | A. Aguezzoul, “Multi-criteria decision making methods for Third-Party logistics evaluation”, in Proceeding of the 2nd IEEE Conference on Engineering Systems Management & Applications (ICESMA 2010), 2010. |

| [9] | A. Aguezzoul, “Overview on 3PL selection problem”, Chapter of Book “Outsourcing of Supply Chain Operations and Logistics Services”, Editions IGI Global, 2012 (accepted). |

| [10] | M. Berglund, P. Van Laarhoven, G. Sharman, and S. Wandel, “Third-party logistics: is there a future?”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 59-70, 1999. |

| [11] | P. Van Laarhoven, M. Berglund, and M. Peters, “Third-party logistics in Europe-five years later”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 425-442, 2000. |

| [12] | W. Delfmann, S. Albers, and M. Gehring, “The impact of electronic commerce on logistics service providers”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, vol. 32, no. 3/4, pp. 203-222, 2002. |

| [13] | K. H. Lai, E. W. T. Ngai, and T. C. E. Cheng, “An empirical study of supply chain performance in transport logistics”, International Journal of Production Economics, vol. 87, no. 2, pp. 321-331, 2004. |

| [14] | E. Bottani, and A. Rizzi, “A fuzzy TOPSIS methodology to support outsourcing of logistics services”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 294-308, 2006. |

| [15] | G. W. Dickson, “An analysis of vendor selection systems and decisions”, Journal of Purchasing, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 28-41, 1966. |

| [16] | C. A. Weber, J. Current, and W. C. Benton, “Vendor selection criteria and methods”, European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 2-18, 1991. |

| [17] | S.H. Cheraghi, M. Dadashzadeh, and M. Subramanian, “Critical success factors for supplier selection: an update”, Journal of Applied Business Research, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 91-108, 2004. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML