Ulisses De Oliveira1, Marcelo Saparas2

1Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil

2Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil

Correspondence to: Ulisses De Oliveira, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The nominal group (NG), in both English and Portuguese, has substantial differences in relation to the order of its constituents. So the comparison of such constituents can shed some light on the issue. We have examined the constituents of the NG in English and their translations into Portuguese in terms of: (a) function, as well as (b) their occurrence order in both languages. As an example, one can realize the Portuguese translation of the following NG: (1) generalizable (2) model (3) of clause and (4) sentence (5) structure, into current Portuguese as “(2) modelo (1) generalizável (5) da estrutura (3) de oração e (4) da sentença” shows that the order of its constituents in both languages differs considerably. The consideration of the semantic/discursive structure involved in it – and not just its morphosyntactic structure – can help us to cope with difficulties such translations can cause.

Keywords:

Portuguese, English, Nominal group, Constituents of the NG, Word order, Translation

Cite this paper: Ulisses De Oliveira, Marcelo Saparas, Syntax: A Comparison between the Nominal Group in English and Portuguese, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2018, pp. 27-36. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20180602.02.

1. Introduction

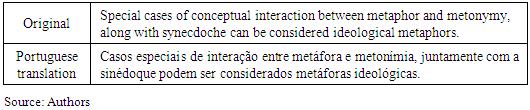

In this paper we intend to examine the nominal group (NG)1 – structure formed by the noun and its modifiers – in both English and Portuguese, by comparing the functions of its constituents, and the order of occurrence of these elements in both languages. As an example, the translation into Portuguese of the NG: “generalizable model of clause and sentence structure” into “modelo generalizável da estrutura de oração e da sentença” shows that the order of its constituents differs considerably from one language to the other. Due to such difference, a number of other translations as the translation of “mental knowledge structure” into Portuguese also led to a dilemma: what would the best translation of this NG be? “estrutura de conhecimento mental” or “estrutura mental de conhecimento”, since Portuguese allows both translations? This type of uncertainty has already happened with the translation of “critical discourse analysis”, which some prefer to translate as “análise do discurso crítica”, while others uphold the “análise crítica do discurso” translation. This issue was addressed by Magalhães (2004/2005). In this sense, Fries (2001) asserts that every linguist agrees with the fact that the NG in English constitutes a complex construction. Perini (1986, p.38) corroborates such idea in relation to the NG in Portuguese, stating that “the constitution of the noun phrase is very complex.”Researchers have been examining such aspect, viz., the identification of functions performed by each modifier in relation to the head of the NG in both English and in Portuguese, and their order within the group. Regarding English, we can mention Huddleston (1984), Quirk et al (1985), Gregory and Asp (1985), Radford (1988), Bathia (1993), Fries (2001), Bruti (2003), Halliday (1994), and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004). About Portuguese, Câmara Jr. (1979), Tarallo (1994), Borba (1996), Kato (1988), Neves (2000), Silva and Dalla Pria (2001), Monte (2006), among others.According to Halliday; Matthiessen (2004), the NG is often equivalent to a complex word – that is, a constructed combination of words based upon a specific logical relationship. Thus, when interpreting the structure of a NG, it is paramount to consider its meaning as a triple organization – experience, evaluation and language – as the expression of certain logical relations, viz., the order in which the constituents remain in the NG. In this context, Silva (2008), examining structures with two adjectives in both Portuguese and English, proposes the choice of syntactic-semantic and discursive principles to explain the placement of the modifier with respect to the noun in this type of structure. In short, it’s the interaction between discourse and semantic-syntactic features of adjectives that foreordain their position within the NG.Following this reasoning, a path to be followed by those who want to establish the order of modifiers in relation to the headnoun in NGs of both languages would depend on the examination of the correspondence between the syntactic and discursive functions performed by the modifiers within the NG in order to be able to check patterns of difference and standardization of the NG’s constituent order in both languages.Our overarching goal in this paper is to establish criteria for the order of NG constituents in both English and Portuguese, based on their syntactic-semantic-discursive functions and examine the NG translation variations from English into Portuguese. The research should answer the following questions: (a) What are the roles and functions of the NG constituents in English and Portuguese? (b) What is the order of the constituents in the English and Portuguese NGs?

2. Theoretical Framework

In order to bring up the criteria that rules the order of the NG constituents in both languages, we will deepen our understanding about: (i) the notion of group, as a level below the clause; and (ii) some proposals regarding the order of constituents in the NG structure in both English and Portuguese.

2.1. The Nominal Group

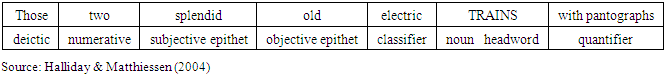

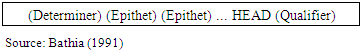

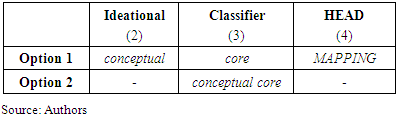

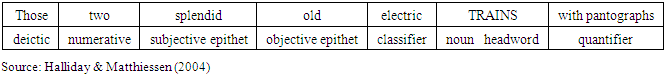

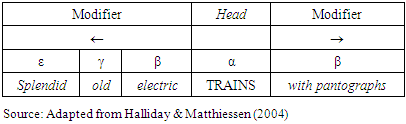

Below the level of the clause, and as part of its constitution, lies the group, according to Halliday (1994), a class composed by nouns, verbs and adverbs (nominal, verbal and adverbial groups respectively) performing different functions in such structure. Biber and Gray (2011), analyzing historical development of nouns as nominal premodifiers and prepositional phrases as nominal postmodifiers, found that dramatic change in the use for these structures occurred in the second half of the twentieth century, when three-noun (e.g. air force machines) and four-noun (e.g. life table survival curves) sequences became more frequent to a point “this extension seems to be continuing up to the present time”. (Biber & Gray, 2011: 240).From a Western grammatical tradition, the group was not recognized as a separate structural unit, and clauses were analyzed directly through its words. It turns out that, according to most authors, the model “clauses through words” is inappropriate because it overlooks several important aspects of meanings involved in communication. For Halliday and Matthiessen the group somehow is equivalent to a word complex, that is, a combination of words built up of the basis of a particular logical relation. Distinguishing between a phrase and a group, Halliday and Matthiessen state that a phrase is different from a group in that, whereas a group is an expansion of a word, a phrase is a contraction of a clause. For example,(1) A red rose (group)(2) With a long nose (phrase = a reduction of the clause “that has a long nose”).We have chosen to analyze the constituents of the NGs in English and in Portuguese as the order of the constituents differ considerably in both languages, causing difficulties for speakers of Portuguese who are learning English and vice-versa.The analysis of the NG, from the perspective of Systemic-Functional Linguistics (SFL) (Halliday, 1994; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) considers the meanings or metafunctions of its constituents, which are: Ideational, Interpersonal and Textual. As in the Ideational metafunction, for example, Banks (2008: 124) conceives that nominalizations have increased in use historically, mainly in physical and biological science, to refer to “material processes” (e.g. separation emergence). He sees mental and verbal processes as also important, which reveals how SFL framework can add clarification to the research of the NG construction and use. Let us examine this organization, in the example suggested by Halliday and Mathiessen (2004):(1) those two splendid old electric trains with pantographs.This NG contains a noun – trains – preceded and followed by several items that characterize it in some way. This occurs in a certain sequence, which is fixed in most cases, according to Halliday and Matthiessen (2004). We can interpret this NG as an Ideational, Interpersonal and Textual framework, which, taken as a whole, has the function of specifying: (i) a class of things (trains); (ii) a constituent category within the class (those, two, splendid, old, electric, with pantographs); (iii) and the sequence of these constituents in the NG, respectively. Chart 1 shows the types and the sequence of constituents in the NG in English, as proposed by Halliday (Idem).Chart 1. The structure of the Nominal Group

|

| |

|

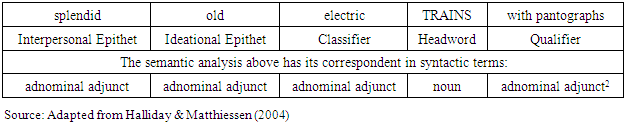

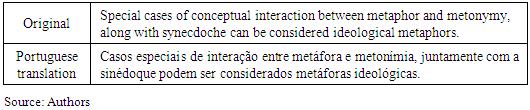

Chart 1 presents the analysis of the NG - (1) “Those two splendid old electric trains with pantographs” - with the head and its modifiers.We must add here that in Chart 2, below, we can notice that the categories of Interpersonal Epithet, Ideational Epithet, Classifier and Qualifier would all be classified as adnominal adjuncts in syntactic terms in accordance with traditional grammar, which is markedly morphosyntatic. The first three ones are usually realized by adjectives, and the last one by a prepositional phrase.Chart 2. The structure of the Nominal Group

|

| |

|

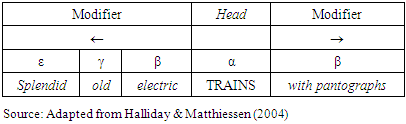

According to the authors, however, each of these morphosyntactic elements has a semantic function: Interpersonal Epithets, with subjective evaluation (author's attitude); Ideational Epithet, objective evaluation (product quality); Classifier, indicating of subclass of the headnoun; and Qualifier, in general, a relative clause reduced to an adjective or a prepositional phrase. Thus, these elements are "terms within different systems of the network of systems" (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004: 312).The categorization within a class is expressed, in the words of Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), by one or more functional elements in English: (i) Pre-Head (PreH) of the NG: Deictic, Numerative, Epithet and Classifier; and (ii) Post-Head (PostH) of the NG – the Qualifier. Next, we will examine the function of PreHs and PostHs in English, according to Halliday; Matthiessen (Idem). In our analysis, the Deictic and the Numerative will be left aside, since they do not represent issues to NG translations; likewise, the Qualifier that keeps the position in the PostHs when translated.• The Deictic performs to specify the head.• The Numerative reveals the quantity or order, which can be exact (e.g., cardinal and ordinal numbers) or indefinable (e.g., many, successive).• The Epithet expresses some sort of quality for the head, which can be an objective feature (Ideational) of the head or the expression of subjective attitudes (Interpersonal) of the speaker in relation to it. There is, however, a thick line between these two Epithets: (i) the Ideational ones are potentially defining, unlike the Interpersonal ones; (ii) Interpersonal Epithets tend to precede the Ideational ones, ordering from the less to a more permanent (“a new red ball” and not “a red new ball”); (iii) the Interpersonal ones tend to be reinforced by other words (e.g. horrible, ugly, great).• The Classifier signals a particular subclass of the head (e.g., electric trains, passenger trains, toy trains). The same word can function as Epithet or Classifier (e.g., ‘fast trains’ can mean ‘trains that are fast’ (Epithet) or trains classified as ‘express’ (Classifier). The sequence head + Classifier can be so closely connected that it is very similar to a compound noun (e.g., chemistry set, building set), indicating an element progression with potential specification, from the maximum to the minimum. The Classifiers do not allow degrees of comparison or intensity (we normally don’t say “a more electric train” or “very electric train”).• The Qualifier is a PostH modifier and, unlike the others, is a prepositional phrase or clause. According to the authors, the Qualifiers are clauses reduced to terms of a clause, with rare exceptions.(2) Guinness, who knighted in 1959, had a long film partnership with director David Lean.(3) The course of military endeavors is very close.(4) Do you read any English novelists who seems to you Kafkaesque?In reference to the NG constituents sequence, the Chart 3 (below) presents the NG structure according to Halliday and Matthiessen, with two progressive setups of Modifiers (one for PreHs, and another for PostHs), each one ultimately depending on the head.Chart 3. Logical Structure of NGs

|

| |

|

In Chart 3, the Greek letters illustrate the dependency relationship in which β depends on α and γ depends on β, and so on, according to the authors. In that event, one proceeds with the quantitative characterization, near the Deictic (e.g., “three balls”); followed by various qualitative features (e.g., “new balls”), ending with the class indicator, more permanent (e.g., “tennis ball”). In this case, there is more than one qualitative feature, the tendency is, again, moving from the less to the more permanent (e.g., “a new tennis ball”, and not “a tennis new ball”).Other scholars have a different view of NGs, as follows.

2.1.1. Some Proposals on the NG Structure in English

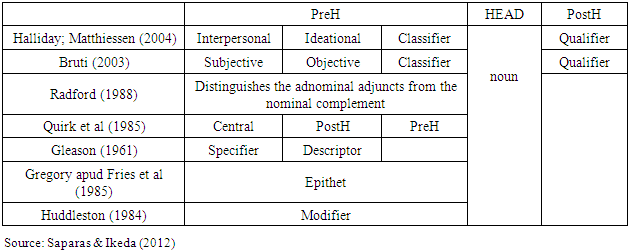

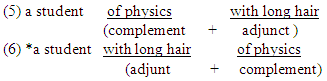

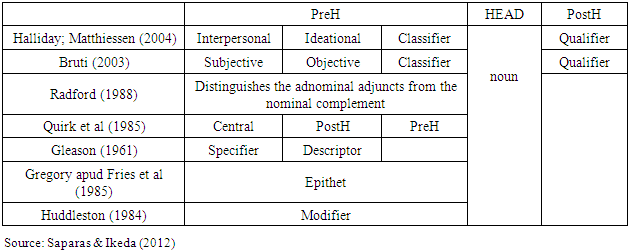

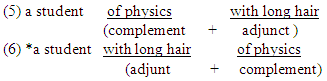

In a study of 2003, Bruti considers the Quantifiers and Deictics that select and particularize the NG head with reference to the context of situation, in English, as being followed by items that describe and classify their more permanent features. Some of these words describe objective qualities (e.g., naked, human), while others are subjective and represent the attitude of the writer (e.g., horrible); however, the difference between the subjective and objective information does not always arrive at a clear reasoning. These words – oftentimes the adjectives – referred to as Epithets, are usually found on a pair-sequence form (e.g., “the smooth, foamless sea”), admitting they can even amount to a sequence of five.Moreover, the author puts forward some rules governing the order of Epithets: (i) size attributes, age, shape and color tend to follow this exact order in English (e.g., “a large, modern, rectangular, black box”); (ii) short adjectives tend to precede the long ones (e.g., “a small, lovely, well-kept garden”); (iii) well-known words are placed before the less common ones (e.g., “a peculiar ante-diluvian monster”); (iv) the most striking of a number of adjectives tends to be placed at the end (e.g., “a sudden, loud, ear-splitting crash”).Others do not describe any quality, however indicate a subclass of the referent (e.g., “human life”), and are named Classifiers. These restrict the entity to a subclass, relating it to another entity (e.g., “army officers”, “football club”). The Classifiers are performed from the general to the specific (e.g., “newspaper advertisement agency employees”).Unlike Classifiers, Qualifiers are all PostH (Bruti, 2003), and serve to define and describe the head a little farther than PreH elements do. Qualifiers add temporary and extrinsic type of information, while PreH constituents are inherent and relatively permanent. That said, this modifier is not an absolutely necessary element to the NG.Radford (1988) accounted for distinguishing adnominal adjuncts from the nominal complement within the modifiers category, based on the fact that the complement is always “closer” to the head than the adjuncts. Compare: Chart 4 sums up the classification of the aforementioned authors.

Chart 4 sums up the classification of the aforementioned authors.Chart 4. The structure of the Nominal Group

|

| |

|

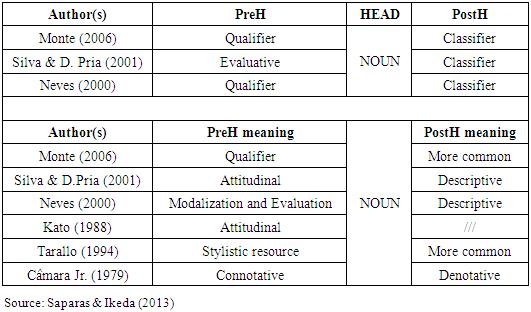

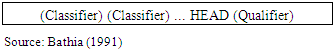

Chart 4 shows the trend in refining the characterization of NGs throughout time. Thus, we see that Halliday; Matthiessen, Bruti and Quirk et al., albeit with different purposes, distinguish three types of modifiers. Bruti mentions the qualifier but believes that this constituent is not essential to the NG. In fact, except for Halliday and Matthiessen and Bruti, the others do not mention the Qualifier.Gleason does not mention the Classifier; Gregory, as well as Huddleton, do not distinguish the different modifiers. Radford sets adnominal adjuncts and complements off from the modifiers. Fries (2001) describes some proposals on PreH and PostH (Gleason, 1961; Gregory apud Fries et al, 1985; Quirk et al., 1985; Huddleston, 1984 apud Fries, 2001).According to Rush (1998), it’s important to shed light on the PreH and PostH order. For example, semantic shifts can happen by substituting one for another in translations into Portuguese because of the different semantic functions of PreH and PostH. In this context, Bhatia (1991) refers to the relation between NGs and the speech genres in which they occur. The author, examining the NGs in professional genres, such as advertising, scientific research and legislative texts, suggests that NGs are markedly different, not only in their syntactic form, but also in their rhetoric function.Thus, the author continues, since one of the main concerns of advertising is to offer a positive assessment of the products or services advertised, and NGs are seen as bearers of adjectives. There is, according to the author, above-the-average probability of occurrences of these modifiers in these genres. Bhatia (1991) provides the following example, outlined in Chart 5.(7) The world's smallest and lightest digital CAMCORDER that's also a digital camera.Chart 5. The NGs in advertising

|

| |

|

Differently, the NGs in written academic genres, especially in science, are used to create and develop technical concepts. These NGs have a structure in which their modifiers are performed by a number of nouns working as Classifiers, and with occasional use of adjectives.Example 8 is a prototypical case, according to Bhatia (1993: 149), where both “nozzle gas ejection” and “space ship altitude” are Classifiers made up by nouns.(8) Nozzle gas ejection space ship altitude CONTROL.Chart 6. The NGs in research paper

|

| |

|

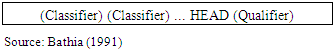

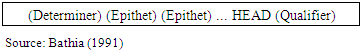

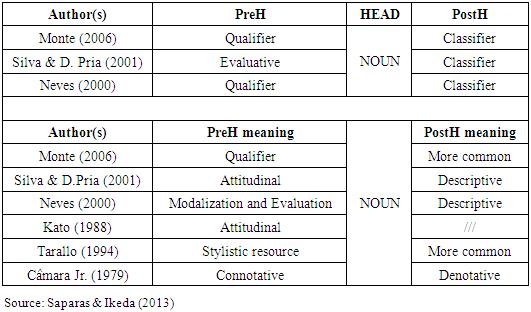

2.1.2. Some Proposals on the NGs Construction in Portuguese

In a similar way in English, in Portuguese, NG differences are not limited to the order of modifiers, but also to its definition. Therefore, Neves (2000) states that adjectives can be Qualifiers and Classifiers.Silva and Dalla Pria (2001) propose the following syntactic-semantic categorization for adjectives in attributive position: determining adjectives, evaluative adjectives and classifiers.Monte (2006), in turn, has classified adjectives in Portuguese into three categories: Qualifiers, Classifiers (preposition + noun, i.e. adjective phrase) and Events (related to the participles of verbs).Câmara Jr. (1975) asserts that there are two implicit factors that establish the placement of attributives in relation to the noun they modify: one is the grammatical order, which is fixed, and the other is free, and is related to the NG constituents order.From a general perspective, there is a consensus regarding the distinction between qualifying adjectives and classifying adjectives. Next, we aim to discuss what is some authors’ stances with reference to the semantic functions of PreH and PostH modifiers.2.1.2.1 PreHs: Pre-modifiers of the Nominal GroupAccording to Tarallo (1994), more than attitudinal, the PreH position is a stylistic resource in literary texts.On the other hand, Neves (2000) sees the PreH Qualifiers as appreciative as well as gradual and intensifying, and expressing both semantic values of modalization (epistemic and deontic) and evaluation (intensification, mitigation and definition).Silva and Dalla Pria (2001) agree that the adjectives in PreH position are attitudinal, ipso facto, they encode the speaker’s view: with PreH adjectives, the noun is taken by the characteristics of adjectives, i.e., the attribute becomes inherent to the noun. Accordingly, these adjectives are used as extensions of nouns, unlike PostH evaluative adjectives. In this sense, Kato (1988) claims that the few adjectives occurring in PreH positon are attitudinal adjectives that encode the speaker's position.As for Borba (1996), Qualifiers, as a way of conceiving the world (assess, evaluate, judge), can take place in two positions, PreH and PostH, with several types of semantic implications. Monte (2006), otherwise, considers that only the qualifying adjectives can happen in PreH position.2.1.2.2 PostHs: Post-modifiers of the Nominal GroupIn his studies, Tarallo (1994) found the PostHs as the most common order in Portuguese (less marked) because they perform the basic functional principle of the system: the maximum information value should be at the end of nominal predicates (heads). For Neves (2000), PostHs have descriptive value.Silva and Dalla Pria (2001) point out that the PostH adjectives determine a subgroup for the designated group by the noun, and express features with descriptive function. Evaluative adjectives are used in dependence with a subjective evaluation and they can occur in PreHs or PostHs, in other words, it can be concluded that evaluative modifiers also take place in post-head position. According to the authors (Idem), classifying adjectives do not express characteristics. Yet, they only relate entities, classifying them.Borba (1996) argues that classifiers, the ones functioning to relate entities, are always PostHs; and for Câmara Jr. (1979), PostHs are denotative while PreHs are connotative.Monte (2006) states that PostHs are the likely position of adjectives in Portuguese. As stated by the author, it may be affirmed that not every qualifying adjective admits PreHs; however, all the prefixed ones admit the PostH position.PreH modifiers usually account for the author’s position connected to the assessment of the noun, while PostHs cling to the description of the intrinsic function of the named object. Moreover, the term “Qualifier” refers to the epithet in a SFL perspective, since the Qualifier, according to SFL, normally occurs in PostH positions, in both English and Portuguese – and it is not a PreH modifier, as shown in Chart 7 by several authors.Chart 7. The NGs in research papers

|

| |

|

Next, we present the proposal of Silva (2008) that extend the discursive dimension to NG studies.

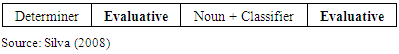

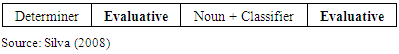

2.2. Discursive Dimension

Silva (2008), when studying the nominal head in Portuguese, stated that the adjectival modification zones could be: determining, evaluative and classificatory. Except for the determining zone, which always remains prefixed to the noun, and the classifiers, which occur in a postponed position, Silva considers that the moving flexibility of adjectives within the phrase in Portuguese is due to evaluative epithets: postponed and prefixed, as shown in Chart 8 (in bold).Chart 8. Syntactical zones of adjectival modification to the Portuguese

|

| |

|

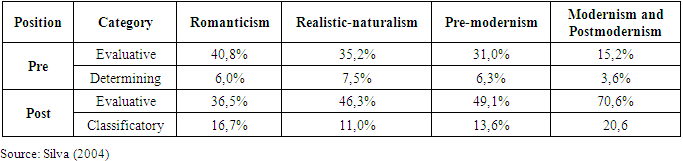

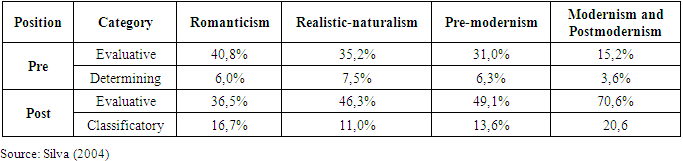

Many grammarians and linguists have been studying the explanation for the reasons of the movement within nominal groups with only one adjective, continues Silva. Both syntagmatic structures exist in Portuguese, and throughout the transformation of this type of language, one of the structures has always outnumbered the other in occurrence. Currently, the postposition of the adjective prevails (Cohen, 1979; Silva & Dalla Pria, 2001, 2002) with different explanations for such fact.Silva (2004, p. 33) analyzes the occurrence of phrases with just one adjective in 16 prose publications of Brazilian literary schools (romanticism, realistic-naturalism, pre-modernism, modernism and postmodernism). Data reveals an increasing reduction of prepositional occurrences throughout the paragraphs, as represented in Table 1.Table 1. Number of Pre and Post positioning in Brazilian Literary Schools

|

| |

|

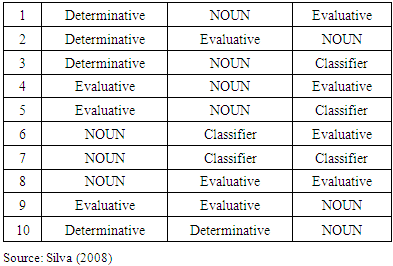

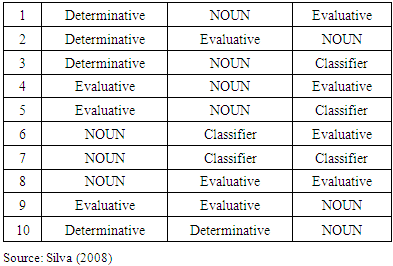

In regard to NGs with two adjectives in addition to the noun, and with reference to the adjectival modification zones in Portuguese that can be: determining, evaluative and classificatory (see Chart 7), Silva (2008) says that these three previous areas enable us to formulate 10 NGs, which explain the possible syntactic-semantic categorizations for the adjective, as presented in Chart 9.Chart 9. The NGs in research paper

|

| |

|

Setting aside the determining positions (always PreH both in English and in Portuguese) and the Classifier (always PreH in English and PostH in Portuguese – zones 3, 5, 10), zones 1 and 2, with respect to the evaluative adjective, refer to the PreH position in English and the PostH in Portuguese (see Table 1).As for the zones in Chart 9, Silva analyzes: (a) Zone 4 – the position of the evaluation depends on the speaker and the statement discursive context (e.g., “big juicy kiss” or “juicy big kiss”); the same explanation covers zone 6 (e.g. “noisy radio station” or “radio station noisy”). It’s noted that in 6 the classifier is always next to the name; (b) Zone 7 – in the case of two classifiers, the argumentative, which is a subject complement (e.g. “sensitive to environmental damage”3) has priority over non-argumentative (one that classifies without being a complement – e.g., “political changes”); (c) Zones 8 (e.g., “facts unclear and useless”) and 9 (“famous intelligent animals created by the cinema”) – in the case of two evaluative adjectives, the order depends on the speaker and discourse context, since one does not imply another. However, in “facts unclear and useless”, it seems to us that there is a logical relationship (cause and effect), that is, facts are useless because they are unclear. Similarly, animals are famous because they are intelligent. Thus, in these instances, the causal relationship tends to influence on the ordering of the elements therefore related, placing the cause before the result.

3. Methodology

This study takes into consideration the semantic-discursive dimension, in addition to the morphosyntactic features, of the NG in English and its translation into Portuguese. The analysis is based on the theoretical-methodological proposal of Systemic-Functional Grammar (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004).The research aims to answer the following questions: (a) What are the roles and functions of NG constituents in English and Portuguese? (b) What is the order of the constituents in the English and Portuguese NGs? To reach the expected answers, we selected and adopted the following data and analysis procedures.

3.1. Data

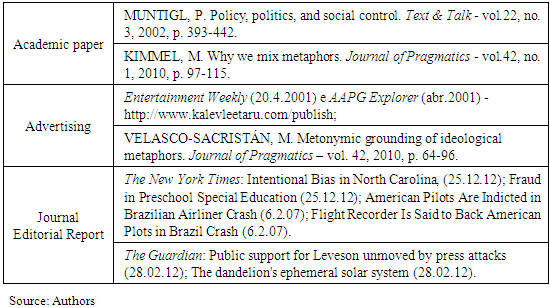

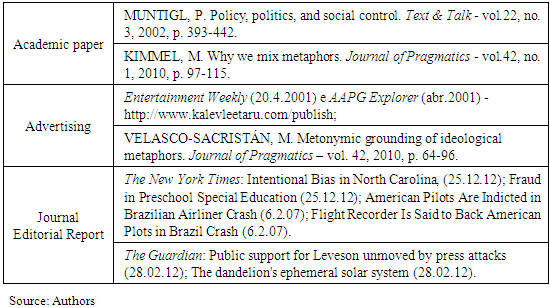

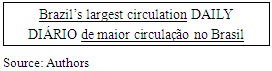

We have examined the NG in the texts presented in Chart 10. The selection of these data was based on texts in English that Brazilian postgraduate students needed to translate into Portuguese during the preparation of their master’s degree and doctoral dissertations4. Perhaps due to the general syntactic complexity of the academic text, or due to a lack of knowledge in the matter expressed by such syntax, fact is that we noted an overall difficulty in the referred translations.Therefore, this was the criteria adopted to select the texts of our analysis. Albeit, there was not a strict pre-selection for this research, we can group them into three different genres, as listed in Chart 10.Chart 10. Research data

|

| |

|

We believe these three genres provide good clarification about the functioning of NGs in both languages. However, the validity of the results may vary depending on the genre and/or the texture of the analyzed sources.

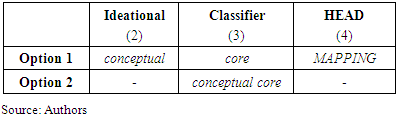

3.2. Analysis Procedures

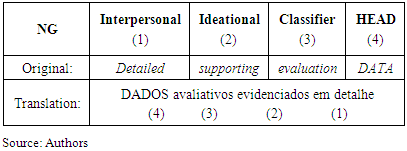

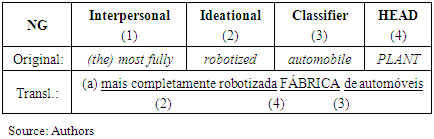

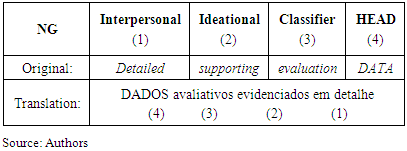

The analysis was made through the following steps. We (a) collected 117 NGs in the cited sources (Chart 10); (b) translated these NGs into Portuguese; (c) did not consider the Determiner, since this component has a fixed position (beginning of NG), both in English and Portuguese. Likewise, we did not consider the Classifier, which also has a fixed position: precedes the noun (PreH) in English, and postpones the noun (PostH) in Portuguese; (d) considered the fact that the evaluative adjectives, also called Epithets, could be distinguished, according to the Systemic-Functional Grammar (Halliday, 1994), as Ideational Epithets, denoting an objective property (cf. “old train”) or Interpersonal Epithets, expressing the speaker’s subjective attitude to the noun (cf. “splendid train”); (e) adopted the nomenclature suggested by Halliday (1994), writing the first letter capitalized (e.g., Epithets, Classifier, Interpersonal and so on) when we referred to the Systemic-Functional Theory concepts. Thus, we avoid the confusion that can happen, assuming that many of these terms have been used by other authors with different meanings at times; (f) enumerated the NG constituents based on their function in order to ease the comparison of the original NG (in English) with translations into Portuguese, as we can see in Chart 11.Chart 11. Analysis of 4-3-2-1 NGs types

|

| |

|

In this example, the noun “data” is modified by a Classifier (evaluative) and by two Epithets (“evidenciados” and “em detalhe”). Note that, in discursive terms, the epithets – whether Ideational or Interpersonal – might depend on the context. As Halliday (1994), conceives there is not a clear line of distinction between these two Epithets.

4. Analysis and Discussion of Results

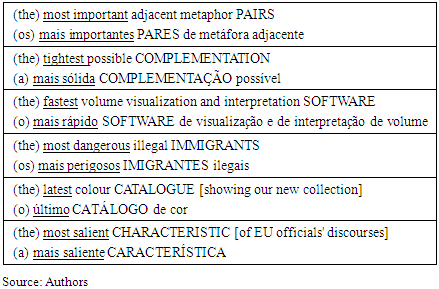

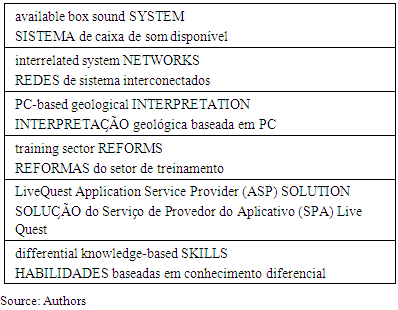

We begin the analysis of the NGs by presenting the English NG first, followed by the translation into Portuguese, then, emphasizing the modifiers that have suffered displacement from the original NG and highlighting the head with capital letters. The analysis showed three reiterated situations with a few exceptions: (a) NGs with the constituents in the order 1-2-3-4 (Interpersonal Epithet – Ideational Epithet – Classifier – head) in English are translated into Portuguese and reshuffled to the order 4-3-2-1 (head – Classifier – Ideational Epithet – Interpersonal epithet); (b) the adjective in the superlative degree has its initial position maintained in the translation; (c) NGs admitting two translations, as demanded by the context, and according to Silva (2008). There are however NGs translations deviating from these groups, that we are naming Specific Cases.

4.1. General Rule: 1-2-3-4 order in English and 4-3-2-1 in Portuguese

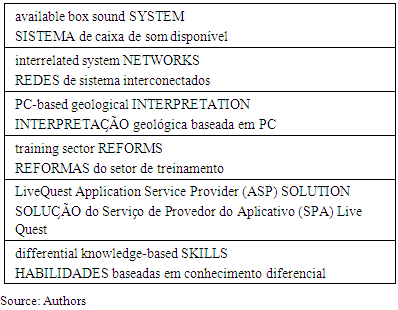

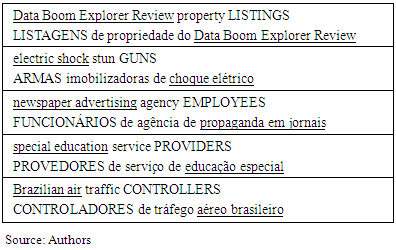

The order 1-2-3-4 in English and 4-3-2-1 in Portuguese translations confirms the forecasts: (i) the fixed position of the Classifier: PreH in English NGs and PostH in Portuguese NGs; (ii) the fixed order of the evaluative adjectives: PreH in English and PostH in Portuguese. This situation5 features what we named General Rule.We present below a few examples of this case in Chart 12. The scarcity of Epithets can be seen, even in the examples collected from advertisements. On the other hand, the Classifier, both in English and in Portuguese, remains next to the head: before it in English; after it in Portuguese. This way, the data demonstrate Halliday’s assertion that the order Headnoun + Classifier is so closely linked that it can be seen as a compound noun (HALLIDAY, 1994: 185).Chart 12. General Rule examples

|

| |

|

Some modifiers are compound, as the ones underlined in the following examples. They follow the general rule though.We can see in Chart 13 that in compound Ideational Epithets, both Epithets have fixed position. For example, “de choque elétrico” (electric shock), a noun phrase followed by an adjective, does not allow a different order, *“elétrico de choque”. This is an issue to be further explored as choices are not always on the author’s criteria: the epithets relate to each other (e.g., by causality, as in item 1.3) for some logical reason.Chart 13. Compound Modifiers

|

| |

|

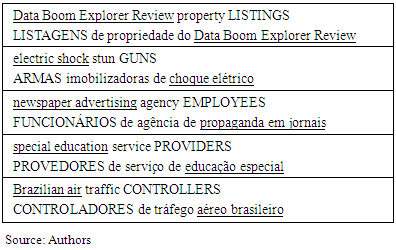

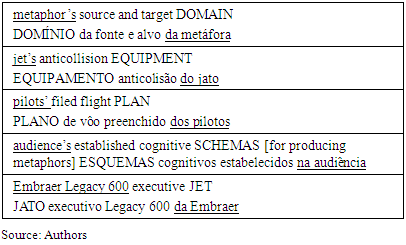

Chart 14. Modifiers involving Genitive

|

| |

|

NGs with genitive, which are translated by the noun phrase, also follow the general rule. According to Halliday (1994), this genitive is a Qualifier (e.g. “source and target DOMAIN of a metaphor”) that would have a fixed position (PostH) if expressed this way.

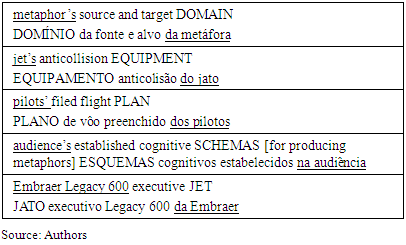

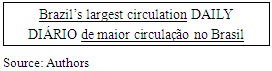

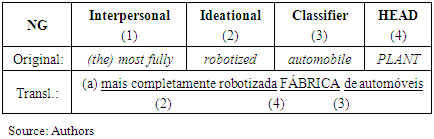

4.2. NGs with Adjectives in the Superlative Degree

Chart 15 presents an adverb (fully) preceded from the article (the), forming the superlative degree of the Ideational Epithet (“robotized”) (Almeida, 2011, p. 151). As shown below, NGs that start with adjectives or adverbs in superlative degree tend to keep the invested element of the superlative degree at the beginning of NGs in translations. This is a case that does not follow the General Rule.Chart 15. NGs with superlative

|

| |

|

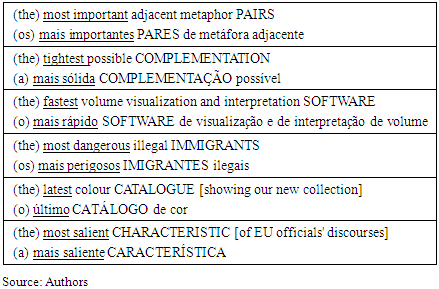

The same can be noticed in different examples: Chart 16. More examples with superlative

|

| |

|

Differently, the following example presents a case of joined superlative + the genitive case, wherefrom superlative becomes PostH:Chart 17. NG with superlative + genitive

|

| |

|

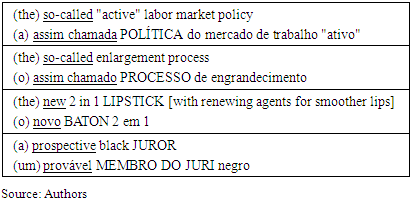

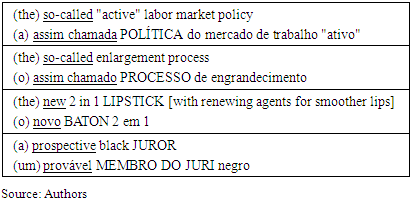

4.3. Other Cases of PreH Persistency in Translation

Similarly, some words or phrases have the property to remain in the same position in two languages, as PreH in this case. The following examples show NGs of this type starting with ‘so-called’ or ‘new’:Chart 18. Other cases of PreH (with ‘so-called’ or ‘new’)

|

| |

|

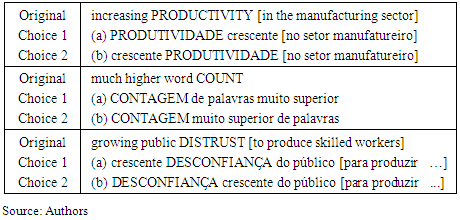

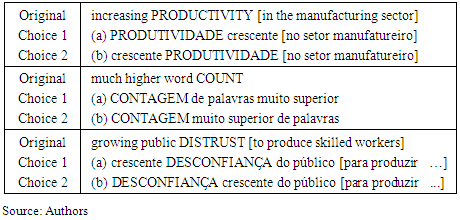

4.4. NGs that Admit Two Orders in Translation

There are cases admitting two different orders in translation in Portuguese, as shown in Chart 19. Halliday and Matthiessen (2004) and Silva (2008) understand that the choice would depend on the author’s will or the discursive context.Chart 19. Double chance of sequence

|

| |

|

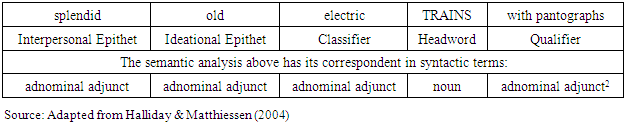

There are cases, however, when the decision to choose between the two alternatives would imply in changing the NG meaning, as in: (a) MAPEAMENTO do núcleo conceitual [...]? (conceptual core MAPPING)(b) MAPEAMENTO conceitual do núcleo [...]?(core conceptual MAPPING)Or, schematically:Chart 20. NGs with superlative

|

| |

|

In academic writing, it is not uncommon for a sentence to include many nominal groups with a broad range in the complexity of the nominal groups. Complex NGs are an expressive feature of academic writing, and the ability to construct complex nominal groups is becoming common at university. They frequently appear in academic texts with the Subject-Predicator-Subject Complement (SPCs) structure, in which two complex nominal groups are joined with a relational process (linking verb). E.g.: “This type of technology and its negative side-effects on the environment, the biggest contributor to pollution in modern society is dependent on substances that this very type of technology provides.”In our corpus we have found a few cases of this type of NG, but their translation into Portuguese basically maintains the same structure of that found in the original text in English. To illustrate, in the chart below, we present an example of a complex NG found in the corpus and its translation into Portuguese.Chart 21. Complex NGs

|

| |

|

5. Conclusions

The analysis considered the SFL proposal, including the semantic dimension in the characterization of the functions of PreHs and PostHs. Although generalizations regarding NGs in English and Portuguese overall would demand an extensive corpus analysis, our study revealed through this corpus that the vast majority of NGs in English occurred in the order: Ideational Epithets – Classifier (2-3) in relation to the head (4). Thus, presenting the order 2-3-4, with rare occurrences of Interpersonal Epithets (1), even in the advertisement genre, when it was expected greater subjective evaluation of the product advertised. Translation postpones the Classifier and the Ideational Epithets (3-2) to the head (4), resulting in the order 4-3-2. This situation characterizes what we call general rule for the NG order.In NGs starting with adjective in the superlative degree, the translation into Portuguese maintains this position. Likewise, certain words like “so called” and “new” keep fixed in the PreH position. With reference to the problematic NG quoted in the introduction (p.ext. “critical discourse analysis”), the translation, according to the general rule proposal, should be “análise do discurso crítica”, since “discurso” is the Classifier and must remain next to the head.There are NGs that admit two orders in translation. These are the cases where the choice of one over the other order requires knowledge of the situational context, viz., the subject matter to which these NGs refer, which includes the consideration of their discursive function in this analysis.On the other hand, there are cases in which the choice should take into account relations, such as causality. This is the case of “unclear and useless facts”, when “unclear” prevails the NG emergence, because it is the cause of “useless” – a semantic implication.In the genres analyzed, we have noted that the Deictic and Numeral are maintained in the same positions in both languages, English (original) and Portuguese (translation). As for the Qualifier, we found that it stays in the same position as the original English (PostHs), fact that facilitates the NG translation. Although it’s not part of this research, there are two situations observed during the analysis that we intend to examine in the future: (a) several NGs occurrences where the headnoun is followed by the preposition “of”, or even a double occurrence of this preposition, followed by a Complement, Qualifier or Appositive; (b) long PostHs, as well as the Qualifier, working as a factor leading to a tendency of balancing the PostH and PreH content: the more extensive the PreH is, the less extensive is the PostH, and vice versa.

Notes

1. “Nominal group” is the expression adopted by Systemic-Functional Linguistics (Haliday, 1994), in contrast to “noun phrase” or “nominal phrase” (abbreviated NP). 2. Rank-shifted, which is equivalent to a clause reduced to a term of a clause. (HALLIDAY, 1994).3. “environmental damage”: damage (noun, “dano” in Portuguese) is the nominalization of “damage” (verb, “danificar” in Portuguese), and calls for a verbal complement, the direct object of “environment”. After the nominalization, the verbal complement becomes a subject complement.4. Postgraduate students in Applied Linguistics and Language Studies (LAEL) from Pontifícia Universidade Católica (PUC- SP).5. Almost 50% of the examined NGs.

References

| [1] | ALMEIDA, Napoleão Mendes. Gramática metódica da língua portuguesa. Saraiva, 2011. |

| [2] | BANKS, David. The Development of Scientific Writing. Linguistic features and historical context (p. 221). Equinox, 2008. |

| [3] | BATHIA, Vijay Kumar. Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings. London: Longman, 1993. |

| [4] | BATHIA, Vijay Kumar. "Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes." World Englishes 16.3 (1997): 313-319. |

| [5] | BIBER, Douglas; GRAY, Bethany. Grammatical change in the noun phrase: The influence of written language use. English Language & Linguistics, 15(2) (2011): 223-250. |

| [6] | BORBA, Francisco da Silva. Uma gramática de valências para o português. Ed. Atica, 1996. |

| [7] | BRUTI, Silvia. "The modifying element." Anno accademico 2003 (2002). Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia Corso di Laurea in Lingue Lingua Inglese I, 2003. |

| [8] | CÂMARA, Joaquim Mattoso. História da lingüística. Editora Vozes, 1975. |

| [9] | FRIES, Peter H. "Toward a Componential Approach to Text1." Learning, Keeping and Using Language: Selected papers from the Eighth World Congress of Applied Linguistics, Sydney, 16 21 August 1987. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing, 2001. |

| [10] | GLEASON, Henry Allan. An Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics. Rev. Ed. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961. |

| [11] | HALLIDAY, M.A.K.; GIBBONS, John; NICHOLAS, Howard. (eds.) Learning, Keeping and Using Language: Selected papers from the Eighth World Congress of Applied Linguistics, Sydney, 16 21 August 1987. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing, 1990. |

| [12] | HALLIDAY, M.A.K. Discourse in society: Systemic functional perspectives. No. 50. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995. |

| [13] | HALLIDAY, Michael; MATHIESSEN, Christian. An introduction to functional grammar. Routledge, 2014. |

| [14] | HUDDLESTON, Rodney. Introduction to the Grammar of English. Cambridge University Press, 1984. |

| [15] | KATO, Mary Aizawa. "A seqüência Adj+ N em português e o princípio da harmonia transcategorial." Letras & letras 4.1-2 (1988): 205-13. |

| [16] | MAGALHÃES, Izabel. "Introdução: a análise de discurso crítica." Delta 21. especial (2004/2005). |

| [17] | MONTE, Carolina. Como o computador deve concordar o adjetivo com o substantivo. http:\\www.filologia.org.br/viiicnlf/anais/caderno14-05.html Access in 15/08/2016. |

| [18] | NEVES, Maria Helena de Moura. Gramática de usos do português. Unesp, 2000. |

| [19] | PERINI, Mário A. Para uma nova gramática do português. São Paulo: Ática, 1986. |

| [20] | QUIRK, Randolph, et al. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Vol. 397. London: Longman, 1985. |

| [21] | RADFORD, Andrew. Transformational grammar: A first course. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, 1988. |

| [22] | RUSH, Susan. "The noun phrase in advertising English." Journal of Pragmatics 29.2 (1998): 155-171. |

| [23] | SAPARAS, M; IKEDA, S. Representações metafóricas em títulos de filmes americanos e suas traduções para o português: um enfoque sistêmico-funcional. 2012. |

| [24] | SILVA, Ademar. "A ordem variável do adjetivo no SN: uma questão semântico-discursiva." Matraga: Revista do PPGL da UERJ 16 (2004): 33-46. |

| [25] | SILVA, Ademar. "A ordem dos adjetivos em grupos nominais: uma questão sintático-semântica e discursiva." Calidoscópio 6.3 (2008): 134-141. |

| [26] | SILVA, Ademar; Dalla Pria, Albano. "A ordem variável do adjetivo em anúncios jornalísticos do século XIX: uma questão semântico-discursiva." ALFA: Revista de Linguística 45 (2001). |

| [27] | TARALLO, Fernando Luiz. Tempos lingüísticos: itinerário histórico da língua portuguesa. São Paulo: Atica, 1990. |

Chart 4 sums up the classification of the aforementioned authors.

Chart 4 sums up the classification of the aforementioned authors. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML