Ashani Michel Dossoumou

Department of English Studies, Faculty of Letters, Languages, Arts and Communication (FLLAC), Laboratory for Research in Linguistics and Literature (LabReLL), University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Abomey-Calavi, BP, Place Lénine, Cotonou, Benin

Correspondence to: Ashani Michel Dossoumou, Department of English Studies, Faculty of Letters, Languages, Arts and Communication (FLLAC), Laboratory for Research in Linguistics and Literature (LabReLL), University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Abomey-Calavi, BP, Place Lénine, Cotonou, Benin.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The aim of this research paper is to appraise the influence of English language’s infiltration in the national languages spoken among, and by the border communities in Benin Republic. Of course, the contact and coexistence of English with indigenous languages have resulted into an inter-linguistic contact phenomenon, mainly among the border communities. This is having significant impact on language dynamics in those areas in terms of speaking of Pure Goungbé, εdέ Anago, and  on the one hand, and/or Mixed Goungbé-English, Mixed εdέ Anago-English, Mixed

on the one hand, and/or Mixed Goungbé-English, Mixed εdέ Anago-English, Mixed  varieties. Such a sociolinguistic dynamics among speech communities culminates with, and leads gradually to the natural phenomenon of language hybridization in the study areas. The data collection for the purpose of this research work was carried out based on the mixed qualitative and quantitative research methods which allow for iterative procedure. This includes a sample size of 183 respondents selected from various socio-professional layers, focusing mainly on age groups, gender and educational backgrounds. Those participants have offered opportunities of observation and interviews in all the settings like households, streets, shops, markets, entertainment centers, and among the travelers crossing the borders. The findings discussion enables to come up with some conclusions on English interference in the local languages and thereby, its indigenization. This results in an emerging hybridization of border communities languages in Benin. Such a situation has become a striking sociolinguistic reality which results from the topical business, communicative and developmental needs and purposes.

varieties. Such a sociolinguistic dynamics among speech communities culminates with, and leads gradually to the natural phenomenon of language hybridization in the study areas. The data collection for the purpose of this research work was carried out based on the mixed qualitative and quantitative research methods which allow for iterative procedure. This includes a sample size of 183 respondents selected from various socio-professional layers, focusing mainly on age groups, gender and educational backgrounds. Those participants have offered opportunities of observation and interviews in all the settings like households, streets, shops, markets, entertainment centers, and among the travelers crossing the borders. The findings discussion enables to come up with some conclusions on English interference in the local languages and thereby, its indigenization. This results in an emerging hybridization of border communities languages in Benin. Such a situation has become a striking sociolinguistic reality which results from the topical business, communicative and developmental needs and purposes.

Keywords:

Indigenous languages, Border Communities, Hybridization, English Domestication

Cite this paper: Ashani Michel Dossoumou, Appraising English Domestication in Indigenous Languages among the Benin-Nigeria Border Speech Communities: A Sociolinguistic Perspective, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2017, pp. 65-74. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20170503.03.

1. Introduction

English language rules the world due to its flexibility. It is the most commonly spoken language in the fields of international business, film, scientific research, inter alia, in line with the prediction made in 1780 by the United States President, John Adams. He envisages that, “English will be the most respectable language in the world and the most universally read and spoken in the next century, if not before the end of this one. According to President Adams, English “is destined in the next and succeeding centuries to be more generally the language of the world than Latin was in the last or French in the present age”. The expansion of English as medium of communication among and between human beings, partners and nations goes increasingly, and to a large extent, leaches into and enmeshing some local languages, which results in phenomenon labeled by sociolinguists as hybridization and creolization.Border demarcation as operated by the colonial masters has made Benin, a Francophone country neighbor to Nigeria which is rather Anglophone. With a border line stretching over seven hundred kilometers, there are constant interactions between the populations living on either side. Moreover, over 80 percent of Benin formal and mostly informal trade activities are carried out through that border line as many families established on Benin territory have to cross-in the border line early in the morning to run their daily activities on Nigerian territory and cross-out in the evening. The same goes on Nigerian side with the tens thousands Yoruba and Igbo running their businesses in border villages Sèmè, Igolo, Owode, Iwoye, Monka, Iloua, Tikandou, Woriya, Yambwan which are the study sites on Benin territory. The very purpose of this study is to investigate the level of English language infiltration and domestication in the local languages spoken among the Eastern Benin border speech communities. In other words, this study measures the levels of Infiltration, Localization, and Indigenization of English into the local languages Goungbé, εdέ Anago, and  (Owusu-Ansah, 1997; Simo-Bodba, 1997) among the Eastern Benin border speech communities. To achieve its purpose, this survey selected three regions of Benin and their respective localities as follows: Ouémé (Sèmè and Igolo borders), Collines (Iwoyé, Monka and Iloua borders), and Borgou (Tikandou, Woriya and Yambwan borders). This study was to measure how the contact of English and those three languages has made significant impact on their use and therefore, generated a kind of creolization. In the process, some social layers of the populations have been considered for individual interviews and focus groups discussions. The age bracket of the 183 respondents is 10-65 years. First and foremost it has been deemed absolutely necessary to provide some conceptual clarifications and definitions in order to keep tract with the readership about the ongoing research work. As such, the paragraph following the introductory part has been entirely devoted to some highlighting definitions and debates around come key concepts including, but not limited to, Border Communities, English language Domestication, Indiginisation, Code-switching, Code-mixing, and Hybridization/ Creolization among the target border communities.The subsequent segment on the inventory of some research works and past scholarships so far carried out by previous scholars has enables to take stock of some them. This has enabled this paper to realize that none of the previous ones has been devoted to this sociolinguistic study of Englishisation of the local languages and Domestication/ Indigenization of English language among the speech communities established and living at the border areas between Benin and Nigeria. Another leg deduced from the review of literature is the adoption of the methodology appropriate for such a study. Due to the very nature of this study, it has been critical to adopt the mixture of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms for data collection, screening, processing and analysis. Iteration has been resorted to, in order to collect additional data and complement the first harvested information.Under the paragraph of discussion, the findings of this research have been presented in tables and commented on. The summary of the results and conclusion close this academic venture.

(Owusu-Ansah, 1997; Simo-Bodba, 1997) among the Eastern Benin border speech communities. To achieve its purpose, this survey selected three regions of Benin and their respective localities as follows: Ouémé (Sèmè and Igolo borders), Collines (Iwoyé, Monka and Iloua borders), and Borgou (Tikandou, Woriya and Yambwan borders). This study was to measure how the contact of English and those three languages has made significant impact on their use and therefore, generated a kind of creolization. In the process, some social layers of the populations have been considered for individual interviews and focus groups discussions. The age bracket of the 183 respondents is 10-65 years. First and foremost it has been deemed absolutely necessary to provide some conceptual clarifications and definitions in order to keep tract with the readership about the ongoing research work. As such, the paragraph following the introductory part has been entirely devoted to some highlighting definitions and debates around come key concepts including, but not limited to, Border Communities, English language Domestication, Indiginisation, Code-switching, Code-mixing, and Hybridization/ Creolization among the target border communities.The subsequent segment on the inventory of some research works and past scholarships so far carried out by previous scholars has enables to take stock of some them. This has enabled this paper to realize that none of the previous ones has been devoted to this sociolinguistic study of Englishisation of the local languages and Domestication/ Indigenization of English language among the speech communities established and living at the border areas between Benin and Nigeria. Another leg deduced from the review of literature is the adoption of the methodology appropriate for such a study. Due to the very nature of this study, it has been critical to adopt the mixture of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms for data collection, screening, processing and analysis. Iteration has been resorted to, in order to collect additional data and complement the first harvested information.Under the paragraph of discussion, the findings of this research have been presented in tables and commented on. The summary of the results and conclusion close this academic venture.

2. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Clarifications

The roles of sociolinguistic codification by which the deep structure of interpersonal relations is transformed into speech performances, in the context of this research are independent of expressed attitudes and similar in nature to the grammatical rules operating on the level of intelligibility. They form part of what Hymes (1972) regards as the speaker’s communicative competence. This competence is expressed through codification. Sociolinguists define a code as the particular language that the speaker chooses to use in any given occasion and the communication system used between two or more parties. According to Wardhaugh (2010), most speakers command several varieties of any language they speak, and bilingualism, even multilingualism, is the norm for many people throughout the world, rather than unilingualism. Once the code established, the norm allows speakers in multilingual speech communities and societies, (as it is the case in the ongoing study) whereby local languages, namely, Goungbé, εdέ Anago, and  spoken by and among the border speech communities, in fine, accommodate and interact with English. So, based on the social, commercial, economic, professional situations induced by the communication setting these speech communities are embarked upon, they can choose to switch or mix codes, as a result of the striking linguistic manifestations of language contact. The two processes of codes alternation involved in such sociolinguistic phenomena are referred to as code-switching and code-mixing.Many scholars and researchers have since, pondered over, and scrutinized the communicative use of code-switching to convey certain social meanings within bilingual communities. In a course of conversation, code-switching describes the shift or switch between languages whether at the levels of words, sentences, or blocks of speech such as what often occurs among bilinguals who speak the same languages. On the other hand, code-mixing describes the mixing of two languages at the words level, (Baker & Jones, 1998). But there seems to be no real consensus among linguists and sociolinguists when it comes to distinguishing between code-switching and code-mixing. According to Fasold (1984), code-mixing can be defined as the use of at least two distinct languages together to the extent that interlocutors change from one language to the other in the course of a single utterance. As for Hudson (1980), she defines code-switching as the speaker’s use of different varieties of the same language at different times and in different situations, which seems to refer more to a diglossic situation. Other sociolinguists rather view code-switching from the perspective of two different languages and occurring only at the level of sentences boundaries. Among them ranges Gingras (1974) who perceives code-switching as the alternation of grammatical rules drawn from two different languages which occur between sentence boundaries. Eventually, Sociolinguists agree to consider the insertion of a single word into the sentence in another language as code-borrowing or lexical-borrowing, and conclude that there are three universal linguistic constraints and/or motivations behind code-switching, namely: the equivalence of structure; the size-of-constituent; and the free morpheme. One way or the other, sociolinguists believe that code-switching is motivated by some social context, affiliation, occupation, or personal affection. Other factors may interplay, such as social prestige and power, language proficiency, social, political and cultural loyalty, avoidance of offensive and/or aggressive words.When a language comes in contact with a new environment, for it to survive, it has to adapt and change so as to reflect the needs of its new environment. English language has become “Home grown” “made native” adapted and tamed to suit the Nigerian environment. This language has been domesticated and acculturated (Adegbija, 2004). Now, it is stretching its tentacles, migrating to conquer other grounds. According to the New Dictionary of Sociology, acculturation is a sociological process whereby an individual or a community of people acquires the cultural characteristics of another group through direct contact and interaction. In the context of this study which is a sociolinguistic dimension, the acculturation of English language among our border speech communities’ languages simply means its “domestication”, “nativisation” or “indigenization” (Otor, 2015). Acculturation and domestication of English among the border communities’ languages are gradually resulting in creolization due to some factors. Those are the symmetrical influence between local languages and English, the adaptation of English to local needs, influence of English on the daily societal activities and influence of local cultures on English. Based on those factors, English is being adjusted through its meaning, vocabulary, semantics, and syntax to local usage because it cannot stand as an isolated linguistic island. May it be English or not, any language serves as medium, thus vehicle of communication of cultural expression and identity. For instance the words “business, sorry, customer, border, engine, credit, car, driver, milk, and sugar” have been nativised and indigenized among those border communities to the extent that they do not cover anymore only their original meanings.

spoken by and among the border speech communities, in fine, accommodate and interact with English. So, based on the social, commercial, economic, professional situations induced by the communication setting these speech communities are embarked upon, they can choose to switch or mix codes, as a result of the striking linguistic manifestations of language contact. The two processes of codes alternation involved in such sociolinguistic phenomena are referred to as code-switching and code-mixing.Many scholars and researchers have since, pondered over, and scrutinized the communicative use of code-switching to convey certain social meanings within bilingual communities. In a course of conversation, code-switching describes the shift or switch between languages whether at the levels of words, sentences, or blocks of speech such as what often occurs among bilinguals who speak the same languages. On the other hand, code-mixing describes the mixing of two languages at the words level, (Baker & Jones, 1998). But there seems to be no real consensus among linguists and sociolinguists when it comes to distinguishing between code-switching and code-mixing. According to Fasold (1984), code-mixing can be defined as the use of at least two distinct languages together to the extent that interlocutors change from one language to the other in the course of a single utterance. As for Hudson (1980), she defines code-switching as the speaker’s use of different varieties of the same language at different times and in different situations, which seems to refer more to a diglossic situation. Other sociolinguists rather view code-switching from the perspective of two different languages and occurring only at the level of sentences boundaries. Among them ranges Gingras (1974) who perceives code-switching as the alternation of grammatical rules drawn from two different languages which occur between sentence boundaries. Eventually, Sociolinguists agree to consider the insertion of a single word into the sentence in another language as code-borrowing or lexical-borrowing, and conclude that there are three universal linguistic constraints and/or motivations behind code-switching, namely: the equivalence of structure; the size-of-constituent; and the free morpheme. One way or the other, sociolinguists believe that code-switching is motivated by some social context, affiliation, occupation, or personal affection. Other factors may interplay, such as social prestige and power, language proficiency, social, political and cultural loyalty, avoidance of offensive and/or aggressive words.When a language comes in contact with a new environment, for it to survive, it has to adapt and change so as to reflect the needs of its new environment. English language has become “Home grown” “made native” adapted and tamed to suit the Nigerian environment. This language has been domesticated and acculturated (Adegbija, 2004). Now, it is stretching its tentacles, migrating to conquer other grounds. According to the New Dictionary of Sociology, acculturation is a sociological process whereby an individual or a community of people acquires the cultural characteristics of another group through direct contact and interaction. In the context of this study which is a sociolinguistic dimension, the acculturation of English language among our border speech communities’ languages simply means its “domestication”, “nativisation” or “indigenization” (Otor, 2015). Acculturation and domestication of English among the border communities’ languages are gradually resulting in creolization due to some factors. Those are the symmetrical influence between local languages and English, the adaptation of English to local needs, influence of English on the daily societal activities and influence of local cultures on English. Based on those factors, English is being adjusted through its meaning, vocabulary, semantics, and syntax to local usage because it cannot stand as an isolated linguistic island. May it be English or not, any language serves as medium, thus vehicle of communication of cultural expression and identity. For instance the words “business, sorry, customer, border, engine, credit, car, driver, milk, and sugar” have been nativised and indigenized among those border communities to the extent that they do not cover anymore only their original meanings.

3. A Brief Account of Some Previous Scholarships

Since this is not a pioneering work in this field of sociolinguistics, many researchers have carried out several research works in the area of code-switching, code-mixing, Englishisation, and indigenization. Therefore, this paper begins by taking stock of the previous scholarships in order to draw on the outstanding and avoid any useless repetition or redundancy. Indeed, this study is on the Sociolinguistics of English language in general, and in particular the variety of English spoken in the neighboring Nigeria and which is being gradually indigenized and domesticated in the national languages (Goungbé, εdέ Anago, and  ) spoken by speech communities established along the border line with Nigeria in Ouémé, Collines and Borgou regions of Benin.As such, while studying the effect of Englishization on language use among the Ewe of Southern Volta in Ghana, Lena Awoonor- Aziaku has revealed that the contact and coexistence between English and Ghanaian indigenous languages has resulted in many language varieties in the country. Three among those varieties are predominant, namely: Pure English, Pure Ghanaian Language(s) and Mixed English. According to the author, the use of any of these varieties as observed depends largely on the social variables such as family type, education, age of the speakers, and the type of communicative settings. Although all the three language varieties appear to be dominant in these informal domains, informants from the younger group, and those belonging to the family type where English only, or English and Ewe are acquired concurrently as the first language by children tend to use most English elements in all the four communicative settings. However, those from the upper age group and those belonging to the family type where Ewe only is acquired by children as first language tend to use the least English elements in all the four communicative settings. Moreover, the study points out another significant observation that conversations by younger generations among their siblings, and conversations with parents, those with children, tend to gear towards English element varieties. That is, the highest proportion of English elements can be found with conversations with younger children and among siblings. Meaning, the participants that are involved in the conversation (communicative setting) have some influence on the choice of language variety in these domains. Some among the respondents even have reported having been dreaming in pure English variety only, a domain which cannot be influenced consciously. The researcher also highlighted an important aspect of this sociolinguistic survey, that the use of pure English and the Mixed Ewe-English varieties are seen as marker for the speech of the young, not obeying the norms of society and using too much prestige variety.On his side, Alobo Jacob Otor has rather focused, zoomed, and projected his spotlight on the challenges and prospects of domestication of English language in Nigeria. In his approach, he has dug deeper into the history of English language in Nigeria and the needs for that language to adapt, to reflect and to suit its new environment. He further looks at the definition of the concept of domestication, as the result of which he establishes that English has been eventually ‘Nigerianised’, that is to say, it has acquired Nigerian nationality. His study has examined the various levels of domestication by covering the lexical, semantic and idiomatic aspects, and discussed the various challenges going along with the sociolinguistic phenomenon under study. Finally he has raised an advocacy and formulated recommendations towards enhancing the full autonomy of English. As according to another leg of his conclusion, there is in Nigeria, an ongoing acculturation of English, and this gives it the status of dialect known as Nigerian English which comes to add to the widening family of New/world Englishes, just like Ghanaian English, Pakistan English, Indian English, American English, Kenyan English. For him the domestication of English in Nigeria enhances Nigerianisation of English due to its distinctive feature. Drawing certainly on the sociolinguistic dynamics of language which stipulates that a language is born, grows, expands and dies, Otor also concludes that English has come to stay and has therefore become Nigerian’s property through its ongoing domestication process. He has further pointed out that even though English was transplanted on Nigerian soil through colonization, it has been accepted. Thus it is high time English language could enjoy the conferment of its full “citizenship” with all the rights, privileges and prerogatives pertaining thereto.In a move to contribute to the ongoing debate in the field of sociolinguistics, Otenaike, Osikomaiya, and Omotayo have in 2012 carried out their reflection on the Emergent Lexis of Nigerian English. From their data analysis, they have pointed out that the lexis of Nigerian English has been established particularly with nouns and other word-classes and has undergone considerable changes among the users. For them, there are some factors which have contributed to prepare and fertilize the ground for the indigenization of English language in Nigeria. Those are, inter alia, nativisation, interference, adaptation and hybridization necessitated by language learning and contact situation in multilingual societies. They conclude that in a bilingual or multilingual situation such as the Nigeria’s, one should not expect the standard form of English as spoken by native users, since all languages have dialects. Thus, Nigerian English should also be regarded as a dialect of English language and not a variety of errors. Investigating more about the dialectology and domestication of English in selected Drama from sociolinguistic perspective, Ojidahun (2014) has focused on the linguistic manifestations of Nigerian English as a dialect of English in the plays of Femi Osofisan. His study has considered, highlighted and identified the sociolinguistic features of domestication of English in Nigeria. He then addresses some of the challenges posed by the domestication process in terms of communication, acceptability, a standard variety, translation and codification. Moreover, the author has further discussed some elements of the domestication of English language from the lexical, syntactic and semantic perspectives. The analysis has revealed that all the sentences in the plays under study are syntactically well formed in English with the lexis available in the English lexicon. But when the sample structures are compared with similar sentences in Standard English, in terms of the meanings they convey, they tend to contrast because Osofisan concocts them to meet the needs of his local readership. Osofisan manipulates the English language to reflect the cultural richness of the Yoruba experience. He takes advantage of being bilingual in English and Yoruba to translate and communicate his vision and experience through a fusion of English and Yoruba languages in such a way that his plays become intelligible to his immediate audience. Femi Osofisan has joined other creative writers of his age in the attempt to domesticate or Nigerianise English. The author eventually opens a window for further research works for the linguistic experts, that is, the issue of codification of the effort by the growing number of creative writers fostering this fascinating technique.Trying to create a national identity along with the effort of domestication of English language for literary purpose in Nigeria, Owolabi highlights that variations are common features of any living language. Pursuing further his reasoning, he states that such variations do not vitiate the importance or acceptability of the various forms, but rather, these variations must be within the confines of acceptable forms that are mutually intelligible. The author thinks that the Nigerian writers who use the English language for literary purpose should also take cognizance of the fact that their variety of English is a pragmatic response to their peculiar situations and environment, without breaking basic rules of syntax and, at the same time, making purists realize that a living language such as English cannot be a closed system. The assessment of any regional variety of English, such as Nigerian English should, therefore, be endonormative rather than exonormative, bearing in mind local peculiarities, and particularly creative and pragmatic use of the language.In their endeavor to contextualize the sociolinguistic perspective of African twenty-first century fiction, Olanipekun, Onanbanjo, & Olayemi, (2016) have reflected against the backdrop of a hypothesis. They postulate that linguistic innovation is not without recourse to domestication, nativisation and acculturation of English language in African fiction. In analyzing the various domestic phenomena of English language in Onyeka Nwelue’s The Abyssinian Boy, the authors have made a significant contribution to the ongoing topical sociolinguistics debate by bridging a critical gap; that of unveiling how the twenty-first century African writers are adventurous about the language medium through skillful deforeignization of the English language in African fiction. They conclude that no matter how Europeanize the borrow medium may look like, certain aspects of the African thoughts, experiences, and worldviews render the language scabbard of African literature to be a conglomeration of linguistic acrobatic pastiche.

) spoken by speech communities established along the border line with Nigeria in Ouémé, Collines and Borgou regions of Benin.As such, while studying the effect of Englishization on language use among the Ewe of Southern Volta in Ghana, Lena Awoonor- Aziaku has revealed that the contact and coexistence between English and Ghanaian indigenous languages has resulted in many language varieties in the country. Three among those varieties are predominant, namely: Pure English, Pure Ghanaian Language(s) and Mixed English. According to the author, the use of any of these varieties as observed depends largely on the social variables such as family type, education, age of the speakers, and the type of communicative settings. Although all the three language varieties appear to be dominant in these informal domains, informants from the younger group, and those belonging to the family type where English only, or English and Ewe are acquired concurrently as the first language by children tend to use most English elements in all the four communicative settings. However, those from the upper age group and those belonging to the family type where Ewe only is acquired by children as first language tend to use the least English elements in all the four communicative settings. Moreover, the study points out another significant observation that conversations by younger generations among their siblings, and conversations with parents, those with children, tend to gear towards English element varieties. That is, the highest proportion of English elements can be found with conversations with younger children and among siblings. Meaning, the participants that are involved in the conversation (communicative setting) have some influence on the choice of language variety in these domains. Some among the respondents even have reported having been dreaming in pure English variety only, a domain which cannot be influenced consciously. The researcher also highlighted an important aspect of this sociolinguistic survey, that the use of pure English and the Mixed Ewe-English varieties are seen as marker for the speech of the young, not obeying the norms of society and using too much prestige variety.On his side, Alobo Jacob Otor has rather focused, zoomed, and projected his spotlight on the challenges and prospects of domestication of English language in Nigeria. In his approach, he has dug deeper into the history of English language in Nigeria and the needs for that language to adapt, to reflect and to suit its new environment. He further looks at the definition of the concept of domestication, as the result of which he establishes that English has been eventually ‘Nigerianised’, that is to say, it has acquired Nigerian nationality. His study has examined the various levels of domestication by covering the lexical, semantic and idiomatic aspects, and discussed the various challenges going along with the sociolinguistic phenomenon under study. Finally he has raised an advocacy and formulated recommendations towards enhancing the full autonomy of English. As according to another leg of his conclusion, there is in Nigeria, an ongoing acculturation of English, and this gives it the status of dialect known as Nigerian English which comes to add to the widening family of New/world Englishes, just like Ghanaian English, Pakistan English, Indian English, American English, Kenyan English. For him the domestication of English in Nigeria enhances Nigerianisation of English due to its distinctive feature. Drawing certainly on the sociolinguistic dynamics of language which stipulates that a language is born, grows, expands and dies, Otor also concludes that English has come to stay and has therefore become Nigerian’s property through its ongoing domestication process. He has further pointed out that even though English was transplanted on Nigerian soil through colonization, it has been accepted. Thus it is high time English language could enjoy the conferment of its full “citizenship” with all the rights, privileges and prerogatives pertaining thereto.In a move to contribute to the ongoing debate in the field of sociolinguistics, Otenaike, Osikomaiya, and Omotayo have in 2012 carried out their reflection on the Emergent Lexis of Nigerian English. From their data analysis, they have pointed out that the lexis of Nigerian English has been established particularly with nouns and other word-classes and has undergone considerable changes among the users. For them, there are some factors which have contributed to prepare and fertilize the ground for the indigenization of English language in Nigeria. Those are, inter alia, nativisation, interference, adaptation and hybridization necessitated by language learning and contact situation in multilingual societies. They conclude that in a bilingual or multilingual situation such as the Nigeria’s, one should not expect the standard form of English as spoken by native users, since all languages have dialects. Thus, Nigerian English should also be regarded as a dialect of English language and not a variety of errors. Investigating more about the dialectology and domestication of English in selected Drama from sociolinguistic perspective, Ojidahun (2014) has focused on the linguistic manifestations of Nigerian English as a dialect of English in the plays of Femi Osofisan. His study has considered, highlighted and identified the sociolinguistic features of domestication of English in Nigeria. He then addresses some of the challenges posed by the domestication process in terms of communication, acceptability, a standard variety, translation and codification. Moreover, the author has further discussed some elements of the domestication of English language from the lexical, syntactic and semantic perspectives. The analysis has revealed that all the sentences in the plays under study are syntactically well formed in English with the lexis available in the English lexicon. But when the sample structures are compared with similar sentences in Standard English, in terms of the meanings they convey, they tend to contrast because Osofisan concocts them to meet the needs of his local readership. Osofisan manipulates the English language to reflect the cultural richness of the Yoruba experience. He takes advantage of being bilingual in English and Yoruba to translate and communicate his vision and experience through a fusion of English and Yoruba languages in such a way that his plays become intelligible to his immediate audience. Femi Osofisan has joined other creative writers of his age in the attempt to domesticate or Nigerianise English. The author eventually opens a window for further research works for the linguistic experts, that is, the issue of codification of the effort by the growing number of creative writers fostering this fascinating technique.Trying to create a national identity along with the effort of domestication of English language for literary purpose in Nigeria, Owolabi highlights that variations are common features of any living language. Pursuing further his reasoning, he states that such variations do not vitiate the importance or acceptability of the various forms, but rather, these variations must be within the confines of acceptable forms that are mutually intelligible. The author thinks that the Nigerian writers who use the English language for literary purpose should also take cognizance of the fact that their variety of English is a pragmatic response to their peculiar situations and environment, without breaking basic rules of syntax and, at the same time, making purists realize that a living language such as English cannot be a closed system. The assessment of any regional variety of English, such as Nigerian English should, therefore, be endonormative rather than exonormative, bearing in mind local peculiarities, and particularly creative and pragmatic use of the language.In their endeavor to contextualize the sociolinguistic perspective of African twenty-first century fiction, Olanipekun, Onanbanjo, & Olayemi, (2016) have reflected against the backdrop of a hypothesis. They postulate that linguistic innovation is not without recourse to domestication, nativisation and acculturation of English language in African fiction. In analyzing the various domestic phenomena of English language in Onyeka Nwelue’s The Abyssinian Boy, the authors have made a significant contribution to the ongoing topical sociolinguistics debate by bridging a critical gap; that of unveiling how the twenty-first century African writers are adventurous about the language medium through skillful deforeignization of the English language in African fiction. They conclude that no matter how Europeanize the borrow medium may look like, certain aspects of the African thoughts, experiences, and worldviews render the language scabbard of African literature to be a conglomeration of linguistic acrobatic pastiche.

4. Methodological Approach

This research paper has adopted both qualitative and quantitative descriptive approaches by using both semi-structured interviews and field observation for data collection. The process of data collection considers respondents belonging to various age groups, socio-professional, educational and sex backgrounds. The gender-based distribution of the one hundred and eighty-three (183) respondents sampled for the study yields eighty-eight (88) males and ninety-five (95) females. The data analyzed in this study were collected between March and April 2017 with the assistance of some local authorities, traditional rulers, and officials working at those border communities, namely the Border Security and Surveillance Unit. All those stakeholders have significantly contributed to facilitating the contact with some respondents. The individual interviews and focus group discussion were definitely carried out based on the respondents’ daily activities, border crossing time, cohabitation with the border officials, and the collaboration with the population on the Nigerian side of the border. Some respondents with relatively inadequate level of fluency in French have been assisted by translators. At some levels, mainly in Borgou region the data collection process was facilitated by a native speaker who assisted in translating the interviews and semi-structured groups’ discussions. Some of the respondents have willingly accepted to receive and discuss with the study team at their house, shops, workshops, markets, football and pétanque ground, entertainment centers, and even in the street. In order to capture all the statements made by the respondents along with the various code-switching and code-mixing use, it has been imperious for the research team to make use of tape recorders during this empirical research. The qualitative method has enabled to measure two varieties of the local languages as spoken among the border communities: the pure variety (pv) and the mixed (creolized) variety (mv). Eventually, the spoken languages in the three regions under study have been investigated along the socio-professional, age, and gender lines. The socio-professional line (A) considers the farmers (A1), traders (A2), and learners (A3). As far as the age line (B) is concerned, it focuses on the following three age brackets: (B1) [10-25]; (B2) [26-49]; and (B3) [50-65]. Last but not the least the gender line (C) among the respondents of the survey has been divided among the Male (C1), Female (C2) and the LGBTIQ (C3).

5. Findings of the Study

Following (Otenaike, Osikomaiya & Omotayo, 2012), (Owolabi, 2012), (Oluwole & Ademilokun, 2013), (Essoh & Endong, 2014), (Ajidahun, 2014), (Ubong, 2014), (Epoge, 2015), (Onyemelukwe & Alo, 2015), (Otor, 2015), and (Olanipekun, Onanbanjo & Olayemi, 2016), the data collected from the border speech communities in those three regions of Benin have treated, extracted, processed and tabulated. Tables 1, 2, and 3 below present the various data disaggregated per region because in each region, only one local language spoken is investigated through its pure use and its mixed type with English. The following step has considered the disaggregation of the collected data along the socio-professional, age and gender category lines and per region.

5.1. Findings among the Border Speech Communities in Ouémé Region

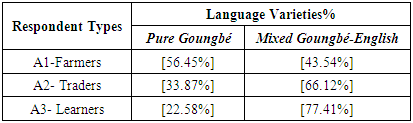

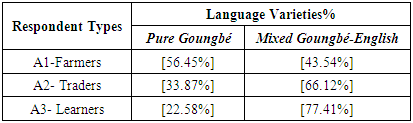

The two border speech communities under study here have been investigated based on Goungbé language which is the most spread and spoken, thus standing as the local lingua franca along the Ouémé region border communities.Table 1 shows that 56.45% of farmers speak pure Goungbé while 45.54% speak the mixed Goungbé-English variety. Those few farmers interviewed in Ouémé region were encountered at Igolo border. At the same time, the distribution among traders shows that 33.87% of the respondents still continue to speak the pure Goungbé variety whereas 66.12% of them prefer the creolized Goungbé-English variety. Among the learners (including apprentices, students, and all the youth going about technical and vocational education and training), only 22.58% practice the pure Goungbé variety; the remaining majority 77.41% speak the mixed-Goungbé English variety for one reason or the other.Table 1. Distribution along the socio-professional lines

|

| |

|

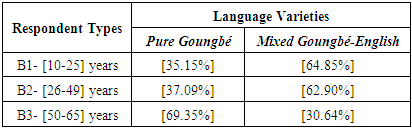

As the findings captured in table 2 exude, only 35.15% of the informants belonging to group B1, that is age bracket [10-25], interviewed within the border community speak the pure Goungbé variety while the majority made up of 64.85% use the Mixed Goungbé-English variety. A similar trend is observed and noted among the respondents of group B2, in age bracket [26-49]. As a matter of fact, the findings reveal that 37.09% with this group speak the pure Goungbé variety, while 62.90% speak the Mixed Goungbé-English variety. It is the informants comprised in group B3, age bracket [50-65] who have reversed the trend with its majority of 69.35% speaking the Pure Goungbé variety, while only 30.64% deem it necessary to speak the Mixed Goungbé-English variety.Table 2. Distribution along the age group lines

|

| |

|

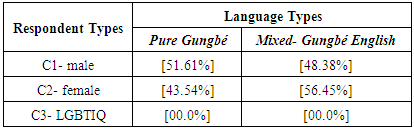

The data in table 3 show that there is an almost equal proportion of the male respondents speaking Pure Goungbé variety and the Mixed Goungbé-English varriety with, respective rates of [51.61%] and [48.38%]. When it comes to the female informants, there is a dominance of the speakers of Mixed Goungbé-English variety with a rate of [56.45%] compared with the proportion of the users of Pure Goungbé variety practiced by [43.54%] of the interviewees. The baffling fact revealed by these data is the 00% LGBTIQ neither among the respondents speaking Pure Goungbé variety, nor among those using the Mixed Goungbé-English variety while communicating, as none of the respondents has ‘dared’ to show up openly as member of this social group.Table 3. Distribution along the gender line

|

| |

|

5.1.1. Discussion of the Findings from Ouémé RegionOn reading carefully the data collected from the two border communities investigated in Ouémé region, there is a striking observation; that of a gradual indigenization, acculturation, and domestication of English language in the largely spread and spoken language of the region. Among the respondents interviewed, those belonging to age brackets [10-25, 26-49], the Traders, Learners, and the women have revealed the preponderant use of Mixed- Gungbé English. Indeed, over 48% among the respondents declare being crossing the border every Monday morning and crossing back the next Saturday on their way back from Lagos where they have no other choice than speaking English. Answering the question about their motivation in so moving, those school-dropped out said to be learning original mechanic like car gear box repair in Nigeria. Others are furthering their education at Alaba, Mile Two, Okokomaiko, Ikoyi, Sango-Ota, Abeokuta, and Ikeja in Accounting, Teaching etc…and equally teaching French language in Nigerian schools. Since they have to be taking courses and interacting with their lecturers and fellows in English over there all week long, they have imbibed the habit of using some English words and expressions. Even when they are back to Benin, they consciously or subconsciously use English words in their normal interactions with their parents and siblings who also willingly accept to follow them in this acculturation of English in Goungbé. In groups A2, B2 and B3 comprising respondents belonging to the group of traders and age brackets [26-49] and [50-65], the majority are users of Mixed- Gungbé English, thus, the creolized variety, just for the purposes of their businesses. Many of them report that they have established their shops at the border area and have to speak small English in order to facilitate communication and trade with their Nigerian customers. Others find it unavoidable to jabber away in English as a result of their constant business-oriented communication and interaction with their Nigerian suppliers including Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa. In any socioeconomic interaction, partners trust more each other in business when they share the same lingua franca. Others again even employ some Nigerians as workers in their companies or as shop-keepers. For some of the remaining respondents, internalizing and domesticating English in their Goungbé are external signs of prestige and wealth they acquired from Nigeria which they have finally adopted as their language role model. All the same, many respondents in those groups have reported having married some Nigerian ladies. The children born from such intermixed marriages are necessarily bilingual because if the Nigerian lady cannot speak French with her children, she would at least interact with them in English. Below are some statements recorded from the informants who accepted to be quoted:A- “I go to Lagos every week to buy vehicles spare parts. I am not wealthy enough to hire an interpreter every time when I have to travel for my business. So the only alternative is to learn the language of my suppliers. There is no other solution. From there Nigerian English started interfering in my Goungbé language. But I cannot do anything against it.”B- “I am learning Mechanic repair of automatic vehicles’ gear boxes. I want to master this job. This is my third year out of the four I should spend to learn and practice it before graduating. Our boss uses to go to Germany for refreshing courses every year. When he arrives back, he teaches us new theories on the Gear Boxes in English before going about the practice. If I cannot speak English, I am lost!! You see? And when I come back over the week-end, I have to show pride in being a Lagosian!!”C- “My shop is established at the border here. My customers who regularly come to buy second hand clothes from me are Nigerians. So I finally resort to recruit a Nigerian shopkeeper, a very nice gentleman, who works with me in the shop. Being working together, we should interact through language. And you know, Nigerians have more problems to learn French than we have in learning English. I finally resolved to speak English with him. I don’t care about grammar, my main objective is to communicate and let my guy understand me, period!”

5.2. Findings among the Borders Communities in Collines Region

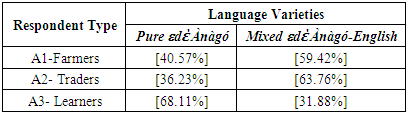

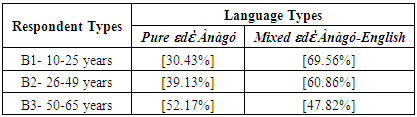

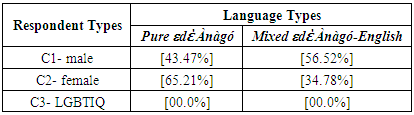

The three border communities under study here have been investigated based on their shared εdὲ Ànàgó which is the most spread and spoken, thus standing as the lingua franca among the Collines region-Nigeria (Ogun and Kwara States) border communities. Historically, this εdὲ Ànàgó (known as Nagot by the French speaking administration in Benin Republic) is one of the former dialects which sprout from the general Yoruba language and which also still exists and is spoken in Nigeria nowadays mostly in the areas of Iwoye, Imèko, Bido-Aïki, Ayégoú etc. History informs that the ancestors of these Anago people established along the border line with Nigeria have, due to rivalry with their brothers over ascending to the throne, migrated from Oyo, Lagos, Ibadan, Abeokuta, and Ilé-Ifè to establish their settlements in Benin. Upon their arrival, they have in the 1300s established one of the oldest kingdoms of Benin, Ààfin Tchábέ upon which commands and reigns Oní Tchábέ. The findings of the interviews and structured group discussions are captured and presented in tables 4, 5, and 6 below.Table 4. Distribution along the socio-professional lines

|

| |

|

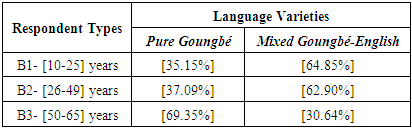

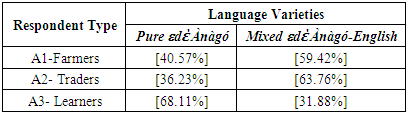

The majority of the respondents interviewed in Collines region are either farmers or traders. But traders happen to be predominant. However, only [36.23%] of the respondents in the group of farmers (A1) use Pure εdὲ Ànàgó variety while a dominant majority of [63.76%] communicate by using Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety. The farmers using Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English are mostly those who have established their farms on the Nigerian side while living in Benin. The other sub-group among those farmers is that of the young laborers commonly known as Àlàgbàshé (seasonal farming laborers) who leave their villages in Benin to go and work as laborers for some share cropping tenants or entrepreneurial farmers. At the end of the cropping season, they get their money and come back home to meet their needs. They come back not only with financial, material resources, but also with linguistic resources displayed through their abundant use of English words while communicating.Regarding the socio-professional group A2 of traders, [40.57%] of the respondents communicate by using the Pure εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety. The other [59.42%] use the Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English. These traders say, they are bound to use some English words while communicating because this is the language they use while on Nigerian side for their business transactions. Some among them have even opened up their mind by pointing out that if they do not show any sign of mastering English while buying goods in Nigeria, their customers and / or suppliers would easily cheat them. As for the sub-group of leaners, those using the Pure εdὲ Ànàgó variety override as [68.11%] belong to that group. Only [31.88%] of the respondents use Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó -English in the course of their discourse. Those learners are the students and apprentices in learning situation in Nigeria and that use to come back home every evening after school hours. Those apprentices come back at the end of their learning period to look for the money needed for their graduation ceremony. Table 5. Distribution along the age group lines

|

| |

|

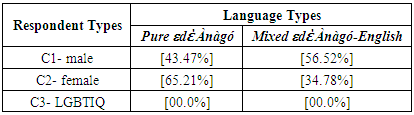

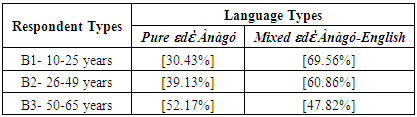

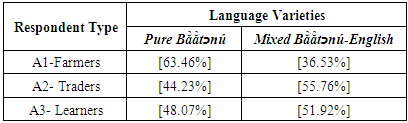

As for the distribution of the respondents interviewed at Iloua, Monka and Iwoyé, the majority use the Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety. As table 5 shows, while [69.56%] of the respondents aged between 10 and 25 years used Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English in their communication with their fellows and parents, only [30.43%] use spontaneously Pure εdὲ Ànàgó variety. As for group B2 comprising informants of age bracket [26-49] years, while [60.86%] report using Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English while communicating, only [39.13%] use Pure εdὲ Ànàgó. Participants of B3 group rather show the opposite trend as [52.17%] of the respondents aged between [50-65] years report using Pure εdὲ Ànàgó, while the remaining [47.82%] report using subconsciously Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety. It is worth mentioning here that the respondents who report using spontaneously Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English are those who are still very active and mobile. Those are the traders, farmers, foreign exchange dealers also known as black marketers, learners and those who have gotten married with Nigerian citizens. Some among the respondents are half-baked citizen emanating from interbreeding or intermarrying between a Beninese and a Nigerian.Table 6. Distribution along the gender lines

|

| |

|

As table 6 exudes, the gender-based distribution of the data collected among the border communities in Collines region shows that [56.52%] of the male respondents encountered in Monka, Iwoyé and Iloua have reported their spontaneous use of Mixed εdέ Anago-English variety, while [43.47%] report using the Pure εdέ Anago variety. Contrary to the male informants interviewed in this region, only [34.78%] among the female respondents have reported using spontaneously Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety during their communication. The remaining overriding majority making [65.21%] rather report using Pure εdέ Anago variety. Here again, the baffling reality portrayed by these data is the 00% rate of the LGBT sub-group neither among the respondents speaking Pure Goungbé variety, nor among those using the Mixed Goungbé-English variety while communicating. None of the informants report to belong to this social group. 5.2.1. Discussion of the Findings from Collines RegionOn reading the data displayed in tables 4, 5, and 6, five groups of respondents visibly show dominance in the use of Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English in communication either with their partners or at home. Those are Traders, [63.76%]; Farmers, [59.42%]; age bracket [10-25] years, 69.56%; age bracket [26-49] years, 60.86%; and the group of male respondents 56.52%. Indeed, this is another indicator of the mobility and interaction between populations on either side of the border. Most of the farmers encountered in those border areas have established their farms on Nigeria side where their brothers, irrespective of the border demarcation drawn by the colonizers, live. The traders report that most of the customers and suppliers from Nigeria speak either Yoruba or Ibo. And for them to effectively ensure a free flow of their transactions, language barrier should be removed and destroyed. For them, by following the Yoruba style of speech, they cannot do anymore without English even while interacting at home with their wives and children. Besides, the use of Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety is a marker of prestige displayed by the traders and, mostly young men who adopt this variety for showing off, more specifically when they have to competitively date a young girl. All those factors have prepared the ground for a domestication of English language in εdὲ Ànàgó. Even though respondents in the upper age group make a preponderant use of pure εdὲ Ànàgó variety, still there are some 47.82% among them who use the Mixed variety. Contrary to (Awoonor-Aziaku, 2015) who report that the Ewe consider the acculturation of English in Ewe language, therefore the use of Mixed Ewe-English variety as a marker for the speech of the young not obeying the norms of their society, and thus as a sword hanging over Ewe language development, the εdὲ Ànàgó speakers rather regard the acculturation of English into their language as a positive linguistic development. For the respondents, this accommodation and domestication of English is a sign of growth for their language and at this very moment, there is no need to attempt any ‘no-go area’ to English when it comes to its indigenization. The Ànàgó informants believe that this is rather an indication of evolution of their language and that they, the peoples in West Africa are ahead of the regional integration that the ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) leaders have been advocated for and promoted unsuccessfully since 1975. See below the concluding statements by some respondents.D- “There is no single day I do not set my feet in Nigeria, because there is my farmland. That enables me to keep in touch with my brothers and sisters over there. When you interact in English at your workplace all day long with people, how can that language fail to influence your speech production even when you are outside your workplace? And you see, for example, the next Báálἐ (Community chief) to be enthroned over there will be from my siblings according to the oracle. You can see that this issue of border demarcation is a useless nonsense set in order to dismantle our social cohesion.”E- “When you are involved in trading and interacting with the Yoruba, you can observe that his/ or her speech is punctuated by some English words. So we also do the same and I can, to a large extent, say that we have been contaminated by the Yoruba people’s style of speech. But beyond that, I can tell you that this issue of Mixed εdὲ Ànàgó-English variety that you are probing will get more serious with the next generation. See for, instance, in our time there was no bilingual school, but nowadays, those schools are spread everywhere, even in our village here our children are learning speaking, writing, listening, and reading skills right from the nursery school. So if you think about stopping the invading wave of English by closing the borders, will you also close the bilingual schools that have been duly authorized to operate?“

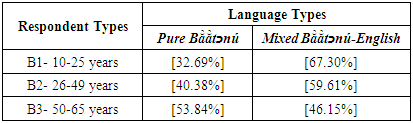

5.3. Findings among the Borders Communities in Borgou Region

The three border communities under study here have been investigated based on their shared  language which is the most shared and spread, thus standing as the lingua franca among the Borgou region-Nigeria (Kwara State) border communities.

language which is the most shared and spread, thus standing as the lingua franca among the Borgou region-Nigeria (Kwara State) border communities.  language is spoken by the

language is spoken by the  people who originated and migrated from Busa (a Nigerian town) to settle and adopt Nikki as the capital city of their kingdom in Benin. 52 respondents have willingly accepted to undergo the interview exercise among the population of Woriya, Tikandou and Yambwan. The three tables 7, 8 and 9 below give a disaggregated rendition of the data collected.

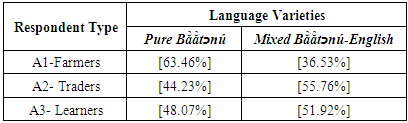

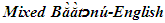

people who originated and migrated from Busa (a Nigerian town) to settle and adopt Nikki as the capital city of their kingdom in Benin. 52 respondents have willingly accepted to undergo the interview exercise among the population of Woriya, Tikandou and Yambwan. The three tables 7, 8 and 9 below give a disaggregated rendition of the data collected. Table 7. Distribution along the socio-professional lines

|

| |

|

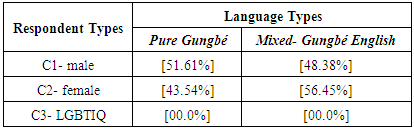

Table 7 above shows that [63.46%], that is a dominant majority among the informants of sub-group A1 (farmers) report speaking  variety while in a speech act condition. Rather, the other [36.53%] of farmers speaks spontaneously

variety while in a speech act condition. Rather, the other [36.53%] of farmers speaks spontaneously  variety in situation of conversation. As for the sub-group (A2) of traders, [44.23%] still continue to speak

variety in situation of conversation. As for the sub-group (A2) of traders, [44.23%] still continue to speak  variety, while the majority in the group use spontaneously

variety, while the majority in the group use spontaneously

variety in their daily commercial activities. The sub-group (A3) of leaners, including school boys and girls, apprentices and other respondents going about technical and vocational education and training on the Nigerian side of the border almost shares equal proportion between the two varieties. Indeed, [48.07%] of the respondents here report using

variety in their daily commercial activities. The sub-group (A3) of leaners, including school boys and girls, apprentices and other respondents going about technical and vocational education and training on the Nigerian side of the border almost shares equal proportion between the two varieties. Indeed, [48.07%] of the respondents here report using  variety, while [51.92%] declare using

variety, while [51.92%] declare using  variety, domesticating therefore English in their daily speech. As the matter of fact, the learners who have reported to speak the

variety, domesticating therefore English in their daily speech. As the matter of fact, the learners who have reported to speak the  variety are those attending school in Nigeria due to the lack of schooling facilities on Benin side. Since the border villages, namely Woriya and Yambwan are close to Okpara river bank the children go early in the morning on board of a motorized boat and come back in the evening.

variety are those attending school in Nigeria due to the lack of schooling facilities on Benin side. Since the border villages, namely Woriya and Yambwan are close to Okpara river bank the children go early in the morning on board of a motorized boat and come back in the evening.Table 8. Distribution along the age group lines

|

| |

|

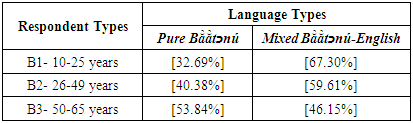

The data in table 8 above shows that only [32.69%] among the respondents belonging to sub-group B1, that is age bracket [10-25] years speak  variety, while the majority in the same age bracket, that [67.30%] speak

variety, while the majority in the same age bracket, that [67.30%] speak

variety in their interaction with their peers and parents. The same trend is observed with the informants of sub-group B2 that is age bracket [26-49] years with the variety proportions [40.38%] and [59.61%] respectively for

variety in their interaction with their peers and parents. The same trend is observed with the informants of sub-group B2 that is age bracket [26-49] years with the variety proportions [40.38%] and [59.61%] respectively for  variety and

variety and  variety. As for B3 of age bracket [50-65] years, [53.84%] of informants report that they use

variety. As for B3 of age bracket [50-65] years, [53.84%] of informants report that they use  variety while [46.15%] interact by speaking

variety while [46.15%] interact by speaking  While the first two sub-groups are still mobile by being involved in many activities including trade, the proportion of the users of

While the first two sub-groups are still mobile by being involved in many activities including trade, the proportion of the users of  in sub-group B3 report that it is due to their children who attend school on the other side of the river.

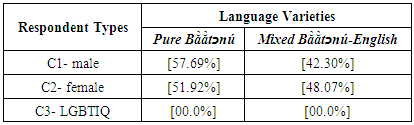

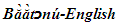

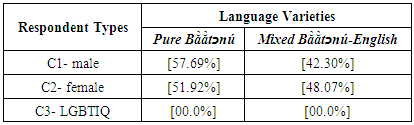

in sub-group B3 report that it is due to their children who attend school on the other side of the river.Table 9. Distribution along the gender lines

|

| |

|

Table 9 shows that [57.69%] among the male respondents report using  variety spoken natively, while the remaining [42.30%] use

variety spoken natively, while the remaining [42.30%] use  variety in their social and commercial interaction. This shows that, though in a relatively lower dominance,

variety in their social and commercial interaction. This shows that, though in a relatively lower dominance,  variety is in use and this is an evidence of the domestication of English among the male

variety is in use and this is an evidence of the domestication of English among the male  Regarding the sub-group of female respondents, [51.92%] have reported that they speak native

Regarding the sub-group of female respondents, [51.92%] have reported that they speak native  variety in their daily interaction while [48.07%] report to be rather speaking

variety in their daily interaction while [48.07%] report to be rather speaking  variety while carrying out their daily activities including the household ones. It is important to highlight the fact that none of the LGBT has been bold enough to show up during the survey and all along our stay in this region.5.3.1. Discussion of the Findings from Borgou RegionAs the data contained in tables exude, there is a preponderance of Pure Bằằtᴐnú variety use among the informants belonging to the sub-groups of farmers A1 [63.46%], age brackets B3 [53.84%], and as well as male C1 [57.69%] and female C2 [51.92%] though this proportion among the gender-based groups are almost equal to those using

variety while carrying out their daily activities including the household ones. It is important to highlight the fact that none of the LGBT has been bold enough to show up during the survey and all along our stay in this region.5.3.1. Discussion of the Findings from Borgou RegionAs the data contained in tables exude, there is a preponderance of Pure Bằằtᴐnú variety use among the informants belonging to the sub-groups of farmers A1 [63.46%], age brackets B3 [53.84%], and as well as male C1 [57.69%] and female C2 [51.92%] though this proportion among the gender-based groups are almost equal to those using  variety. As for the use of

variety. As for the use of  variety, the data rather show a dominance among four of the sub-groups, namely A2 [55.76%], A3 [51.92%], B1 [67.30%] and B2 [59.61%]. Some informants among the traders disclose that their customers are not natives of Busa town, so they rather speak English for their transactions rather than

variety, the data rather show a dominance among four of the sub-groups, namely A2 [55.76%], A3 [51.92%], B1 [67.30%] and B2 [59.61%]. Some informants among the traders disclose that their customers are not natives of Busa town, so they rather speak English for their transactions rather than  That is why they cannot do without using some English words in their daily speeches even though it is in a les dominant proportion. The majority of

That is why they cannot do without using some English words in their daily speeches even though it is in a les dominant proportion. The majority of  variety users belong to the sub-groups of traders and learners who are very much involved in activities inducing mobility departing to and from Nigeria. The majority of those who relatively use

variety users belong to the sub-groups of traders and learners who are very much involved in activities inducing mobility departing to and from Nigeria. The majority of those who relatively use  variety report doing their activities with interactants belonging to the same

variety report doing their activities with interactants belonging to the same  ethnic group but living on Nigerian side. None of those sub-groups realizes 100% use of

ethnic group but living on Nigerian side. None of those sub-groups realizes 100% use of  variety in their speech act, this means that there is already a hybridization in their language production whatever its proportion. F- “Only about five years ago, all our two border community members here in Woriya and Yambwan did experience a severely-bitter situation. Indeed about 34 of our children perished in a capsized boat due to engine failure or break down in the deep water while the water flow was extremely speedy. Of course since we do not have school facilities on Benin side, all our children go to school free of charge, every morning, on the other side of Okpara river in Nigeria, and come back in the evening. We are more or less quarantined and secluded here on Benin side, when it comes to enjoying such social amenities. Since we know that Education is crucial for our children, above all, we have to speak our little English with them so as to help them keep the momentum while they are out of school vicinities. In so doing they would not eat pounded yam with the little they have learnt during the day. Also, we are not financially capacitated and wealthy enough to recruit home teacher for them. Even if we did have money, the manpower does not exist!! That is what motivates our choice for English. And when we proceed that way, they succeed brilliantly and we are happy, because they are our hope.”The other striking fact evidently displayed at all the study areas or communities is the voidance of LGBTIQ. Nobody has dared showing up as member of that minority group. People said to be ready to excommunicate and eradicate such atypical social cankers in their living environment. Of course, those three communities are adamantly hostile to the emergence of such social abnormalities because they are feudal and family-centered.

variety in their speech act, this means that there is already a hybridization in their language production whatever its proportion. F- “Only about five years ago, all our two border community members here in Woriya and Yambwan did experience a severely-bitter situation. Indeed about 34 of our children perished in a capsized boat due to engine failure or break down in the deep water while the water flow was extremely speedy. Of course since we do not have school facilities on Benin side, all our children go to school free of charge, every morning, on the other side of Okpara river in Nigeria, and come back in the evening. We are more or less quarantined and secluded here on Benin side, when it comes to enjoying such social amenities. Since we know that Education is crucial for our children, above all, we have to speak our little English with them so as to help them keep the momentum while they are out of school vicinities. In so doing they would not eat pounded yam with the little they have learnt during the day. Also, we are not financially capacitated and wealthy enough to recruit home teacher for them. Even if we did have money, the manpower does not exist!! That is what motivates our choice for English. And when we proceed that way, they succeed brilliantly and we are happy, because they are our hope.”The other striking fact evidently displayed at all the study areas or communities is the voidance of LGBTIQ. Nobody has dared showing up as member of that minority group. People said to be ready to excommunicate and eradicate such atypical social cankers in their living environment. Of course, those three communities are adamantly hostile to the emergence of such social abnormalities because they are feudal and family-centered.

6. Conclusions

This study has been premised on appraising English domestication in indigenous languages among the Benin-Nigeria border communities from sociolinguistic perspective. The review of previous scholarships has enabled to ascertain the originality of the study, but also to adopt the appropriate methodology to guide the data collection, screening, and processing. The analysis of the findings has shown that the contact between English, Goungbé, εdὲ Ànàgó, and  continues to influence the speaking of those national languages among the study speech communities. Moreover, this study has revealed that the contact and interaction between local languages and English have first resulted in their hybridization and gradual Englishisation with English language being domesticated and indigenized in its use. The various factors that have induced such a domestication of English in indigenous languages are the societal activities which constrain the actor’s adoption of some sociolinguistic and linguistic behavior in a particular situation. Therefore, sociolinguists should no longer regard language and society as separate and different kinds of reality. Bernstein (1961) has pointed out that verbal communication is a process in which actors select from a limited range of alternates within a repertoire of speech forms determined by previous learning. And this selection is ultimately a matter of individual (and in actual fact, collective) choice moved by socioeconomic, developmental, educational, and commercial interests.Therefore, flowing along with Afolayan (1982), this study believes that borrowing, code-mixing, code-switching from English are not as unimportant in Goungbé, εdὲ Ànàgó, and

continues to influence the speaking of those national languages among the study speech communities. Moreover, this study has revealed that the contact and interaction between local languages and English have first resulted in their hybridization and gradual Englishisation with English language being domesticated and indigenized in its use. The various factors that have induced such a domestication of English in indigenous languages are the societal activities which constrain the actor’s adoption of some sociolinguistic and linguistic behavior in a particular situation. Therefore, sociolinguists should no longer regard language and society as separate and different kinds of reality. Bernstein (1961) has pointed out that verbal communication is a process in which actors select from a limited range of alternates within a repertoire of speech forms determined by previous learning. And this selection is ultimately a matter of individual (and in actual fact, collective) choice moved by socioeconomic, developmental, educational, and commercial interests.Therefore, flowing along with Afolayan (1982), this study believes that borrowing, code-mixing, code-switching from English are not as unimportant in Goungbé, εdὲ Ànàgó, and  as some may try to make out. I would say, on the contrary, that it is futile to discourage that process as this would waste energy. Besides, if we are to enrich our languages at all, we may have to translate, borrow, adapt, adopt, acculturate, indigenize and domesticate names, ideas, notions, and concepts from as many languages as we possibly can, because the alternative to this will prove to be tedious, slower, irrelevant, and/or untenable. Therefore, what we need to do is to organize, if possible, borrowing, code-switching, code-mixing and English language domestication processes in such a way that they cover only the main patterns that are missing in our national languages. Moreover, it is extremely important to avoid indulging any linguistic chauvinism and narrow-mindedness so as to be able to develop and improve the languages, and enrich them with notions, ideas, concepts, and objects that would reflect the views of a wider world. The cogent reality is there. The promoters of pure varieties of Goungbé, εdὲ Ànàgó and

as some may try to make out. I would say, on the contrary, that it is futile to discourage that process as this would waste energy. Besides, if we are to enrich our languages at all, we may have to translate, borrow, adapt, adopt, acculturate, indigenize and domesticate names, ideas, notions, and concepts from as many languages as we possibly can, because the alternative to this will prove to be tedious, slower, irrelevant, and/or untenable. Therefore, what we need to do is to organize, if possible, borrowing, code-switching, code-mixing and English language domestication processes in such a way that they cover only the main patterns that are missing in our national languages. Moreover, it is extremely important to avoid indulging any linguistic chauvinism and narrow-mindedness so as to be able to develop and improve the languages, and enrich them with notions, ideas, concepts, and objects that would reflect the views of a wider world. The cogent reality is there. The promoters of pure varieties of Goungbé, εdὲ Ànàgó and  among the border communities should learn to accept, cope with, and think positively about these sociolinguistic phenomena going along with linguistic paradigms shift in a developing society.

among the border communities should learn to accept, cope with, and think positively about these sociolinguistic phenomena going along with linguistic paradigms shift in a developing society.

References

| [1] | Adegbija, E. (2004) “The Domestication of English in Nigeria” in Awonusi, S. and Babalola, E.A (eds) the Domestication of English in Nigeria Lagos: University Press. |

| [2] | Afolayan, A. (1982). Yoruba Language and Literature. Ibadan: University of Ife Press. |

| [3] | Awoonor-Aziaku, L. (2015). The Effect of Englishization on Language Use among the Ewe of Southern Volta in Ghana. India: International Journal of English Language and Literature Study. Vol 4, No 4, p 192-202. ISSN (e):2306-0646. ISSN(p): 2306-9910. |

| [4] | Brownson, E M. (2012). Sociolinguistic Consciousness and Spoken English in Nigerian Tertiary Institutions. In English Language and Literature Studies. Vol. 2 No 4, p 43-52. ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Canada: Canadian Center of Science and Education. |

| [5] | Coker, O. & Ademilokun, M. (2013). An Appraisal of the Language Question in Third-Generation African Fiction. In The African Symposium: An Online Journal of theAfrican Educational Research Network. Vol. 13, No. 2, ISSN# 2326-8077. |

| [6] | Epoge, N. (2015). Domestication of English in Africa via proverbial expressions: A lexico-semantic study of transliteration in the English of Akɔɔse native speakers in Cameroon. In Globe: A Journal of Language and Communication. Vol.2, p55-69. ISSN: 2246-8838. |

| [7] | Essoh, N. E. & Endong, F. P. (2014). French Teaching in Nigeria and the Indigenisation Philosophy: Mutual Bedfellows or Implacable Arch-Foes? In Journal of Foreign Languages, Cultures and Civilisations. Vol. 2 No 1, p145-157. ISSN: 2333-5882 (Print), 2333-5890 (Online). |

| [8] | Hudson, R.A. (1980). Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| [9] | Hymes (1972). Towards Communicative Competence. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. |

| [10] | Kishe, A.J., 1994. The englishisation of Tanzanian Kisiwahili. World Englishes, Vol. 13 No 2 p185-201. |

| [11] | Mesthrie, R. et al. (2009). Introducing Sociolinguistics (2nd edition). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. |

| [12] | Mesthrie, R. and R. Bhatt, 2008. The study of new linguistic varieties. World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| [13] | Ojidahun, C. O. (2014). The Domestication of English in Femi Osofisan’s Drama: A Sociolinguistic Perspective. In Marang: Journal of Language and Literature. Vol.24, 2014, p82-95. |