-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

p-ISSN: 2326-0750 e-ISSN: 2326-0769

2015; 4(1): 11-17

doi:10.5923/j.linguistics.20150401.02

Making Nigerian English Pedagogy a Reality

N. H. Onyemelukwe1, M. A. Alo2

1Department of Languages, School of Liberal Studies, Yaba College of Technology, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria

2Department of English, Faculty of Arts, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: N. H. Onyemelukwe, Department of Languages, School of Liberal Studies, Yaba College of Technology, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study re-awakens the scholarly concept of Nigerian English (NigE) as a new English (NE). It has, howbeit, noted that NigE is not yet a subject-language. Domestication is identified and explicated in the study as the theoretical basis for the academically neglected NE. Hence, it highlights the indispensable need for NigE pedagogy as well as its constitutional entrenchment as the national language of Nigeria. NigE pedagogy is considered imperative in the study for its immense academic and other benefits the foremost of which include the reversal of the current massive failure in Standard British English (SBE) language and other subject examinations and the strengthening of national unity in the country. Underpinning the above benefits to prompt immediate implementation of its pedagogy is the fundamental postulation, that unless NigE is used for academic, research and everyday communication purposes, it will eternally be considered a mere scholarly concept, which invariably implies that Nigeria will remain perpetually under-developed, because a strong correlation exists between linguistic proficiency and overall national development. Consequently, the study proposes and expounds some modalities for its pedagogy, recommending that the pedagogy be anchored on M.A.K. Halliday’s Systemic Functional Theory (SFT), since as a NE, it is highly contextualized and the SFT emphasizes contextual and functional meanings.

Keywords: Nigerian English, Domestication, Pedagogy, New English, Linguistic Proficiency

Cite this paper: N. H. Onyemelukwe, M. A. Alo, Making Nigerian English Pedagogy a Reality, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 11-17. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20150401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The concept of Nigerian English (NigE) is scholarly no longer a controversy. It has been elaborately explicated in numerous works prominent among which include Banjo (1995, 1996), Adetugbo (1987), Adegbija (1989), Bamgbose (1971, 1982, 1995), Akindele & Adegbite (1999), Alo (2004), and Mestbrie (2004) as well as Akere (1978). The list of previous works that objectified the concept as seen above suggests that it was born in the mind of linguists by early seventies. Before then, however, it has been pragmatically codified by fiction writers in Nigeria especially Chinua Achebe (1958, 1960 and 1964) who also partly dwelt on it, non-fictionally in his Novelist as a teacher (1973). Hence, Oha (2004:293) states that evidence from Nigerian literature appears to support the nativization of English in Nigeria concurring that this evidence reflects in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (TFA), No longer at Ease (NLAE) and Arrow of God (AOG). The foregoing evinces that Nigerian English has firmly taken root among global New English(es) (NE).Nevertheless, as firmly rooted as NigE is acclaimed to be right now, its pedagogy is still far from being a reality. In other words, standard Bristish English (SBE), and American English (AME) to some extent, remain the instructional media in Nigerian schools at all levels. This paradoxical situation in our view, explains why NigE is yet to attract scholarly recognition beyond the shores of Africa. Yes, because no list of NE in any international dictionary or encyclopedia contains NigE. See Crystal (2006) as well as Typhoon international (2004. Xii-Xvi) and all editions of the Oxford Advanced Learners’ Dictionary of Current English.Consequently, some Nigerian linguists who are culture enthusiasts like Isola as well as Adekoya (2008) generally hold that Nigeria is still a colonial colony which has graduated from having one to ‘serving two colonial masters’: Britain and America. In the opinion of the culture custodians, no country has ever developed speaking a foreign language. Hence, to them, Nigeria remains subjugated and underdeveloped and will so remain, having suppressed her indigenous languages in favour of English her official, commercial, instructional, and therefore national language, as noted in Oha (2004) and Olajire (2004:462). The culture enthusiasts rightly interpret Nigeria’s under-development in linguistic terms, because language conveys culture and culture broadly defined, includes development concepts and parameters, including scientific and technological knowledge and applications. From this developmental perspective language has been and remains the soul of every society and is, therefore, indispensable in the development of any society such as Nigeria. See Adeyanju (2002:527). Hence linguistic provenance as asserted by Mackey (1984:43) as cited in Bamgbose (2004:1-2) becomes a marker of inequality among nations as among ethnic groups:There is hardly a sovereign state on earth that does not contain language minority: some have several including aboriginal, colonial or immigrant language groups. Yet, although of equal potential the languages of these minorities are not of equal educational value. All languages are equal only before God and the Linguist.The above quotation implicitly underpins Britain and America’s hegemonic edge over Nigeria. Simply put, their English adopted by Nigeria have caged the nation’s socio-economic potentials. This deduction is bluntly clarified by Fishman (1996:628):The world of large scale commerce, industry, technology and banking, like the world of certain human sciences and professions is an international world and it is linguistically dominated by English almost everywhere, regardless of how well established and well-protected local cultures, language and identities may otherwise be. The last two paragraphs before this certainly justifies the emergence of NigE, the benefits of which are yet to be fully derived on account of its zero pedagogy. This paper, therefore, undertakes to scholarly re-awaken the academic as well as the socio-cultural and political needs of the NE and make a case for its introductory and sustained pedagogy for the purposes of stimulating the exploitation of its full potentials the realization of which would accelerate overall development of Nigeria.

2. The Theoretical Premise for Nigerian English and Its Pedagogy

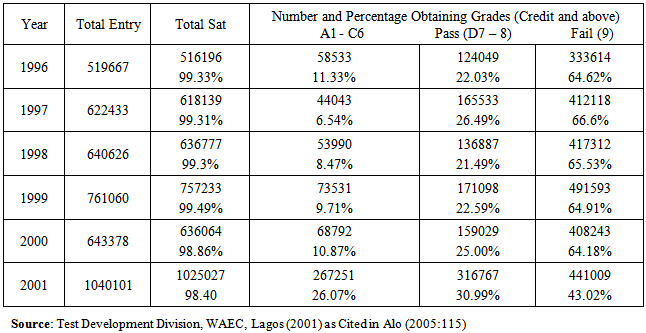

- NigE originated from the linguistic notion of domestication. Domestication, as deducible from the works of linguists such as those cited in the introductory part of this study, refers to the various changes undergone by a language in the course of its spread and implantation in alien speech communities. These various changes occur at all levels of linguistic organization: morphological, lexical, syntactic, semantic and even rhetorical. Hence, if a language is said to have been domesticated, it presupposes that the use of the language, especially for oral communication, has gone beyond the regional boundaries of its native speakers. Such a language, consequently, boasts of very numerous speakers with variants of geographical spread. This being the case, it takes on and retains the respective local colours appropriate to the various ethno-cultural millieu where it has been domesticated. The direct implication of the foregoing is that NigE is domesticated English (SBE), the Britons being the native speakers of the language. Consequently, following Bamgbose (1995:26), we identify NigE as nativized or ‘Nigerianized’ English. In other words, NigE refers to English as spoken by Nigerians, which is now a NE just as American, Canadian, Scottish, Irish and New Zealand English. Being a NE, it is now a language of its own because it possesses linguistic features which clearly differ from those of SBE. Some scholars like crystal (1997) and Typhon (2004) would consider it a variety of English just as they typify other new Englishes. So, typified, it becomes a dialect of English. Nevertheless whether it is a language of its own or a dialect, it is unarguably the current expression system of Nigerians employed for both their oral and written communication.Some scholars such as Brann (1975) and Prator (1968) consider NigE a linguistic aberration because in their view, it embodies the totality of deviations from SBE. Howbeit, these deviations signify the domestication which in the words of Adegbija (2004:21), has given birth to NigE. In relation to the initial attempts of Nigerians to learn how to speak English strictly in the English way, the deviations naturally arose as a direct function of interference from their mother tongues. This interference has since been scholarly pinpointed to stem from the learners’ ignorance or involuntary transfer of the linguistic features of the mother tongues to the structures of English, their target language. See Duskova (1969:29), Carl (1980:22) and Wilss (1977:265). In our view, the transfer theory better accounts for mother tongue interference than ignorance hypothesis, which explains why the interference still features significantly in the English spoken and written by highly educated Nigerians- university graduates and lecturers, for instance. This English spoken and written by highly educated Nigerians corresponds to varieties IV and III of use of English by Nigerians as differentiated by Brosnahan (1958) and Banjo(1996), respectively. The above explication indicates that what Brann and Prator identified as deviations are indeed regular features of the use of English by Nigerians, now rightly identified as NigE. The emergence of NigE is a necessity: a necessity that embeds the need to communicate concepts and modes of interaction alien to English culture, but integral to Nigerian culture. Cf. Bamgbose (ibid.). It is, therefore, correct to concur with Adegbija (2004: 20) that NigE is home-grown. It is home-grown, and so, substantially different from SBE to suit the Nigerian environment, the Nigerian culture. As such, it serves as an appropriate vehicle for expressing and transmitting Nigerian culture, whether it is professional or unprofessional culture, material or non-material culture.If, as our ‘culture-conscious’ linguists claim, NigE does not sufficiently articulate Nigerian culture which consequently hampers development, it is because of the academic negligence it currently suffers. Academically, it currently suffers negligence, because it is not yet a subject-language in Nigerian schools. In other words, Nigerian schools continue to teach SBE/AME even at the university level at which NigE was conceptualized and identified. Currently, at the primary and tertiary levels, SBE is exclusively the target language, whereas at the secondary level it is a mixture of SBE and AME, but the former is accorded more recognition than the latter. Succinctly put, SBE is virtually the target language in Nigerian educational system now. AME attracts recognition, albeit residually, at the secondary level due to WAEC and NECO’s ‘performance ego’ which appears to favour the students, but has in reality done them more harm than good. The ego prompts the two examination boards to accept AME expressions from students, if they are consistently employed, for the purpose of reducing failure rate in English. Nevertheless, every year a great majority of the students mix up both SBE and AME in their SSCE in English, as a result of which failure in English language examinations at that level remains massive. The situation is so bad that no more than 20% of WAEC and NECO candidates credited English in 2008 and 2009. The statistics represent the picture created by WAEC’s official revelation that less than 14% of her candidates obtained credit passes in five subjects including English and Mathematics in each of the two years. For NECO, less than 11% and 2% of candidates obtained the same quality of results in the two respective years. Retrospectively, considering credit passes and above, the statistics remain the same for the period, 1996-2001 as evident in the table 1 below:

|

3. Implementing Nigerian English Pedagogy

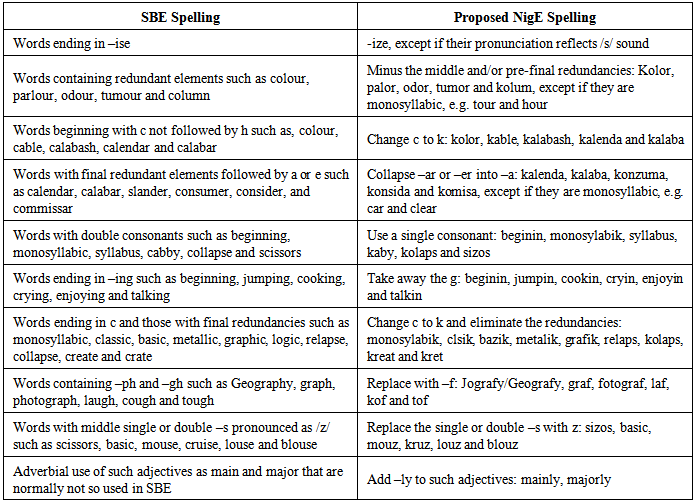

- It is one thing to adopt an orphan child, but another to give the child due parental care. Similarly, it is one thing to domesticate a language, but quite another to develop and sustain the resultant home-grown variety of the language. Nigerians have rightly domesticated the English language. However, the onerous task of developing and sustaining the linguistic product of the domestication remains to be accomplished. In other words, there is a very serious need to develop and sustain NigE, otherwise, it remains a NE only in principle, but not in reality. Hence, this need is imperative and cannot be satisfied without the implementation of NigE pedagogy. This implementation should be motivated by the same patriotic ideology that informed the development and spread of SBE from the 13th century onwards by virtue of which it reclaimed superiority and domination over Latin and French Languages, especially during and after the renaissance. Alberti’s defence of his use of the vernacular (SBE) for a scholarly work in 1434 when Latin was a superior international language reflects such ideology:I do not see why our Tuscan of today should be held in so little esteem that whatever is written in it, however excellent, should be displeasing to us… and if it is true, as they say, that this ancient language (Latin) is full of authority… only because many of the learned have written in it, it will certainly be the same with ours if scholars will only refine and polish it with zeal and care. (Baugh, 1951: 245)Richard Mulcaster’s 16th century exhortation to his fellow country men and women in his Elemontaire also epitomizes the ideology:The question is not to disgrace the Latin but to grace our own language-English. I do not think that any language is better able to utter all argument with more pith or greater plainness than our English Language. (Carol, 1962:63 as cited in Onyemelukwe, 1990:14)Concurring with Mulcaster, we assert that no language, but NigE is suitable to articulate the Nigerian cultural sensibilities and nuances. Consequently, we consider the need to implement its pedagogy ‘a matter of life and death’ in terms of the speakers’ overall socio-economic and political development, since that is the only means by which it can be developed and sustained and developing and sustaining it is critically fundamental to national development in Nigeria.How can NigE be developed and sustained? Insights from language development as a concern of Linguistics show that no language can be considered developed without proper codification. To codify a language is to organize the identifiable features of the language into a grammatical system in accordance with its use and usage in both oral and written communication. The distinction between Language use and usage is contained in Alo (2005: 114-115) and Onyemelukwe (2011). The grammatical system of a codified language consists of such components as lexicon, syntax, semantics and phonology. Each of these components is very formerly and clearly mapped out in the corpus of the language. The corpus ‘diglossifies’ the language and defines the functions of its high (H) and low (L) varieties and is continually updated by a legally recognized body of linguists. Another factor in language development is its use for. Hence, a developed language should and must be used for teaching and learning purposes. The language should, therefore, be a subject-language at all levels of education, and so, can be used for research purposes. The role of lexicography and lexicographers in this regard is indispensable. Their role is indispensable, because no language can be scholarly useful without dictionaries. Sustaining a developed language is the same as keeping it constantly in use for intra/inter-personal cum intra/inter-national communication.With reference to NigE, codification has been arbitrarily achieved as evident in the works cited in our foremost introductory paragraphs and Nigerian literatures generally, especially the novels of Chinua Achebe. Hence, the need arises to harmonize these existing codifications. The need for harmonization arises, because the codifications are not entirely homogenous and raises the question of standardization. See Alo (2005: 122) and Oha (2004: 295). To resolve the issue and consequently evolve standard NigE, we propose a meticulous harmonization of its varieties II and III as delineated by Banjo (1996:73-93) for their endonormative value. Each of the two varieties can also distinctly constitute non-standard and sub-standard NigE varieties, respectively. This proposition, automatically, equates the standard variety to its written form and its other varieties to its spoken form. It is also our proposition that Nigeria English Studies Association transforms to Nigerian English Studies Association and liaise with the Federal Ministry of Education, WAEC and NECO and other relevant government organs such as the National Council on Education and National Universities Commission (NUC) to legally establish a National Language Commission that will immediately be assigned the responsibility of standardizing NigE. The commission may want to incorporate other arbitrary models of NigE into its standardization, such models as has been delineated by Bamgbose (1982) as well as Akindele & Adegbite (1999). The emergent standard model from the proposed harmonization can recognize the following orthographical recommendations.Recognizing the spelling system proposed in table 2 will mean the elimination of virtually all redundancies. It will also mean spelling words as phonically as may be reasonable as well as adverbial formation by a simple addition of –ly to an adjective. Recognizing the spelling system will not be out of place and in no way prescriptive, because many Nigerians’ daily text (SMS) messages largely reflect the orthography as seen in the samples that follow:

|

4. Academic and Other Benefits of Nigerian English

- Implementing NigE pedagogy as proposed above with or without modification has immense academic benefits. If it is effectively implemented, Nigerian students, at all levels within a record time, will be liberated from the retrogressive consequences of massive failure that is currently their fate in relation to SBE. In other words, Nigerian students will soon achieve linguistic proficiency, since by virtue of the implementation, they will begin to speak and write Nigerian English, which is much less methodical than SBE. Moreover, every other variable being favourably constant, their failure rate in all other subjects or courses of study will be reduced to the barest minimum. The failure rate will be so reduced, because linguistic proficiency is a veritable key to knowledge acquisition. See Ikonta and Ezeana (2004: 432-444). Consequently, teaching and learning outputs will geometrically increase and produce quality research works that would drive accelerated national development in every sector including political leadership. This desirable and expected positive effect is certain to materialize, since as noted in Onyemelukwe (2008), there is a strong correlation between national development and linguistic proficiency.The next academic benefit of NigE pedagogy is the increased self-confidence that will result from students’ linguistic proficiency coupled with a more beneficial social interaction among them, even outside the school setting. These benefits will continually increase with the students’ advancement in oral and written NigE communication. Again, the NigE teacher will face less challenge as regards methodology in connection with the right grammatical theory to adopt. He will simply exploit the theoretical premise of M.A.K. Halliday’s (1973, 1978, 1985 &1994) Systemic Functional Theory (SFT) and adapt the teaching methods that suit the framework as expounded by Ogunsiji (2004:19-34). The SFT, for its emphasis on meaning, is the right grammatical theory for NigE pedagogy, because it is a highly nativized (context-driven) grammatical model just as NigE is a highly nativized (context-conditioned) SBE. See Alo (2005:116). High teacher motivation is another academic benefit of NigE pedagogy. Onyemelukwe, Ibeana and Obioha (2012) identifies low teacher-motivation as a direct consequence of massive failure in SBE, but the reverse will be the case as the foregoing evince.In addition to the above academic benefits, the nationalization of NigE which will follow its pedagogy will ultimately resolve the national language question. Resolving the national language question will immediately strengthen national unity in the country for invaluable political benefits. Consequently, no ethnic group will ever again feel constitutionally marginalized. The feeling of marginalization will become history with the crumbling of the constitutional recognition presently accorded Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba as co-national languages to SBE. The recognition is right now a factor, because as correctly argued by Oha (2004: 280-295), the centering of a language by means of constitutional recognition in a pluralistic ethnolinguistic state like Nigeria amounts to both linguistic subjectivity and political subjugation against the ethnic nationalities whose languages are denied such recognition. That is, linguistic domination is equal to political domination. This assertion precisely captures the Nigerian situation now. Hence, it is indisputable that crumbling Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba as co-national languages will surely mark the end of the political domination of the ‘minorities’ by these ‘major’ ethno-linguistic groups. The cessation of this majority-minority dichotomy which incorporates national unity will naturally translate to political maturity and high national economic growth, subsequently. Cf. Onyemelukwe (2008). Invariably, crumbling SBE as Nigeria’s national language, and by extension, AME, will in the long run dissolve the current British and American international socio-economic hegemony over Nigeria, which sometimes assumes a socio-political dimension.

5. Conclusions

- This study has re-awakened the scholarly concept of NigE as a NE. It has, howbeit, noted that NigE is not yet a subject-language. Domestication is identified and explicated in the study as the theoretical basis for the academically neglected NE. Hence, it highlights the indispensable need for NigE pedagogy as well as its constitutional entrenchment as the national language of Nigeria.NigE pedagogy is considered imperative in the study for its immense academic and other benefits the foremost of which include the reversal of the current massive failure in SBE language and other subject examinations and the strengthening of national unity in the country. Underpinning the above benefits to prompt immediate implementation of its pedagogy is the fundamental postulation, that unless NigE is used for academic, research and everyday communication purposes, it will eternally remain a mere scholarly concept, which invariably implies that Nigeria will remain perpetually under-developed. Consequently, the study proposes and expounds some modalities for its pedagogy, recommending that the pedagogy be anchored on M.A.K. Halliday’s Systemic Functional Theory, since as a NE, it is highly contextualized and the SFT emphasizes contextual and functional meanings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML