-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

p-ISSN: 2326-0750 e-ISSN: 2326-0769

2015; 4(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.linguistics.20150401.01

Socio-Linguistics, Oral Literature as Language Socialization and Representation of Identity among Young Nigerian Undergraduates: A Study of Unical and Crutech Slangs

Francis Mowang Ganyi, Stephen Ellah

Department of English and Literary Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Francis Mowang Ganyi, Department of English and Literary Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Identity formation is desirous among human beings and can come in different forms or through different actions or activities. Social or cultural identity however, is achieved through behaviour and most importantly through linguistic behaviour of groups or ethnicities that speak a common language and so express their culture and ethical values through their unique language. Language on the other hand is pervasive and dynamic in the sense that it is prone, not only to extinction, but also to growth and development. We therefore, find that while some languages that once served as identity markers for some ethnic groups have gone into extinction, others are flourishing and absorbing other cultural groups. The English language is one such dynamic language that has been prone to metamorphosis thus, producing several other variants in addition to Standard English. It is this potential for dynamism and eligibility for change and adaptation to situations that has prompted this survey into coinages that approximate to English but with adaptations to Local Social needs and situational variables in University campuses. The aim is to decipher how these coinages serve not only social functions of identity formation but also literary functions like the creation of a unique literary language for the expression of an aesthetic principle for a Nation.

Keywords: Socio-linguistics, Oral Literature, Social Identity, Literary Identity, Nigerian Undergraduates, Student Language, Social Dialects, Speech bunds, Unical, Crutech

Cite this paper: Francis Mowang Ganyi, Stephen Ellah, Socio-Linguistics, Oral Literature as Language Socialization and Representation of Identity among Young Nigerian Undergraduates: A Study of Unical and Crutech Slangs, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20150401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The problem of identity is universal and age old. The search for identity, whether political, social, religious or even literary has been a human indulgence right from creation and perhaps has best been articulated in no other form than in literary or artistic works. In religious parlance, even the fall of Adam and Eve can be traced to or explained from the perspective of the quest for identity because Eve succumbed to the Devil’s temptation only when she was informed of hidden knowledge which could be accessible to them through eating the forbidden fruit. In their quest for an identity that was equal to their creator, Adam and Eve ate of the forbidden fruit – Gen. 3:1-6.Literary works have at all times, therefore, attempted to portray this human quest for actualization at different stages of human evolution. Several writers have equally attested to the paramount social function of literature as being the quest for identity or actualization and fulfillment and the creation of an ideal. T. S. Elliot (1962) asserts that the greatness of a literary work cannot be determined solely by literary and aesthetic standards, but also through the sociological relevance of the work within the environment of its creation. On his part, F. R. Leavis (1952) in The Common Pursuit, recognizes the importance of literature in the quest for identity when he asserts that “Political and social matters should only be examined by minds with real literary education and in an intellectual climate informed by a vital culture (Pp. 193)”. He then sums up his argument by asserting that “In analyzing these works for their sociological relevance, one should not restrict his analysis to only works that have been “printed and preserved”, but rather extend the analysis to those works “whose subtlety of language and complexity of organization can be appropriately and appreciatively evaluated”” (Pp 193.)These would include all oral utterances or constructs that possess literary merit since Oral literature, by modern definition, includes all unwritten forms which can be regarded as possessing literary qualities. It is also from this perspective that Webster and Kros Krity (2013) have strongly argued that literature emphasizes socio-linguistic constructs which serve as empowerment indices to traditional communities in modern day power-play and the politics of globalization. To them, literary language provides the society with- Tacit forms of power which tries to reposition and restore power and importance to those speakers of language groups, who, through consistent marginalization have tended to be obliterated in terms of the global power-play characteristic of the modern literacy dominated world. These same socio-linguistic constructs or literary language specially created to reflect group social or cultural needs could, therefore, be utilized for the creation of a social identity for any class or group of people that create a unique language of expression which serves to portray their uniqueness and identity. Applying this same argument to the African environment that is prone to orality or orature, one finds that most literary constructs exist in Oral forms for the expression of ideas and the sustenance of a cultural identity. Here it is manifest that speech is dominated by proverbial expressions, witticisms, riddles, aphorisms and in some cases long drawn out anecdotal narratives meant to educate and infuse African knowledge systems into the younger generations. These speeches or talks are aesthetically constructed to solicit appreciation of beauty and the impartation of knowledge and are therefore unique to the African environment dominated by Orality. What is worthy of note here is that in the traditional context, all of these creations are carried on within the ambit of a traditional language or socio-linguistic ambience that is mutually intelligible to everyone operating within the same familiar cultural milieu thus creating an identity that unifies and binds traditional communities together as well as defining their world view and ethical values.However, by accident of our colonial experience, we have a second language i.e. English or L2, foisted upon us which has become the major means of communication over and above our traditional or tribal languages. The big question that now arises is, when we operate outside our familiar traditional enclaves, how is meaning i.e. literary meaning or even social identity achieved within the new socio-linguistic context? This question is pertinent particularly when we realize that the communicator, whether in literary or social parlance, manipulates language and adapts the rhythms, register, syntax and semantics of the new i.e. the English language to suit the linguistic and cultural nuances of his native language which has conditioned his thoughts and ideological framework right from the onset. We, therefore, find that social groups in the modern context tend to attempt to maintain an identity that distinguishes them from other groups or from their traditional society through language distinctiveness either along age, tribal, gender, religious or social lines.In this sense, undergraduate students in different Nigerian universities have often developed speech forms that are unique and specific to their needs and which can be considered as language that is creative and can pass for Oral literature created by and for the specific group and portraying their unique identity. These creations, therefore, more often than not, emanate from institutions of higher learning but gradually permeate the wider society and eventually get picked up by writers who use them for written literary constructs. Writers like Late. Ken Saro Wiwa, the Late Ezenwa Ohaeto, Gabriel Okara, Benson Tomoloju and others have variously experimented with this kind of language in their creative writings even though they ended up being criticized for their failure to reach a wider audience because of the restrictive codes they employed. Despite this situation, however, it can still be argued that their experiments accorded a distinctive African cultural identity to the text and have been engendered specifically for and as a response to the problem of language in African literature. This is the problem that could also be addressed through these coinages by students or more specifically what we here refer to as “student language.”

2. Language and Literature

- This is the recurrent problem of language in African literature which Niyi Osundare (2004) re-echoed when he observed that “the problem of language which has dominated African literature in the past fifty years is as a result of the recognition, amongst African Scholars and writers, of the centrality of language to literature.” The argument simply is that a work of art is a cultural construct and as such stands to the identity of its producers and must, therefore, be created from the political, economic, historical and cultural antecedents of the people. It must also make use of a language or linguistic expressions that are indigenous to and able to reflect these experiences. An Alien or foreign language, it is argued, cannot adequately reflect the social, political or cultural landscape of a people since the alien vocabulary will not adequately express local ideas and belief systems indigenous to the people. In this vein, Oral literature in African indigenous languages would be more helpful and appropriate since it would encompass analysis of the literary as well as artistic aspects of individual creativity in each language and in the older forms or even new emergent forms. Since Oral literature can best be explicated as an inter-disciplinary artistic endeavor, its study and in-depth analysis will better flourish on a kind of mutual interchange between the several disciplines of anthropology, socio-linguistics and folklore. It is for this reason that “student language” is being analyzed from the perspective of socio-linguistics, since it is most rewarding to combine insights provided in socio-linguistics, performance and ethnographic studies espoused by Scholars like Richard Bauman, Dell Hymes, Rothenberg, Briggs and a host of others. But the realities of our operational environments today are different from our traditional societies. Today, we the so-called educated elite are forced to operate at two levels, since as bilinguals we think in our local dialects but express our thoughts and ideas in an alien or foreign language. To surmount this predicament, writers and even the Nigerian public, have variously adapted the English language to their specific needs as necessitated by the operative situations they find themselves in. These adaptations have been described as Africanization, Indigenization, Domestication etc. and consist simply of coinages that serve to clarify meaning in given contexts and are used by groups to create and sustain an identity while also projecting an aesthetic principle on which contemporary traditional literary constructs can be built. The situation has, therefore, given rise to several varieties of the English Language in the Nigerian environment while Standard English still remains the general advocacy.Despite this our peculiar predicament, however, one can sufficiently argue that the new varieties of English or coinages as the case may be, which approximate to Standard English do serve purposes of communication in their specific situations of use and can, therefore, be regarded as reflective of the continuous attempt to arrive at acceptable means of presenting African literature and identity to the outside world. After all, to properly understand English Literature, Africans have had to study and decipher the subtle nuances of the English language. Non-Africans who do not understand African languages can also learn these new forms or varieties in other to properly analyze African literature from this perspective, because the varieties are easily intelligible to Local indigenous speakers of African languages among whom these varieties have been developed. Pidgin as a language is generally very intelligible just as the Warri dialect of English which forms of expression easily come handy to aid the vivification of experience. Because of their peculiar origin, nature and contexts of use, these forms are closer to Standard English and so can more easily be understood than traditional Nigerian languages.

3. Methodology

- Because of the peculiar experiences that we are inadvertently exposed to, I have adopted a literary and socio-linguistic approach to the analysis of undergraduate speech forms and coinages that attempt to establish social relationships between groups along lines of tribal affinity, age, gender, status or religion. A Social dialect i.e. “student language” is, therefore, identified on its socio-cultural relevance and literary merit and attempts are made to decipher the extent to which this “student language” has been influenced or how a socio-dialect has developed according to group needs to enhance articulation of ideas and social experiences and for the expression of the school environment. I have also chosen a socio-linguistic and literary approach specifically because undergraduate language or modes of expression are often unique and creative and easily pass as literature of a particular class of people. It can also serve as language coined for specific purposes that satisfy the needs of this class of language users i.e. undergraduates from different social backgrounds living together and having the same needs and outlook on life and can, therefore, serve as a speech bund. The creative potential derives from the way these coinages are manipulated by individual users or groups on specific occasions and the fact that they soon permeate society through students’ interaction with people outside the confines of the University environment. Creativity is evident in the elevated and graphic representation of ideas which qualify these coinages for consideration as a kind of Oral literature. As a result, they are easily adopted and adapted by the public and writers can also make use of these expressions to articulate the ideological standpoint of certain classes of people. The fact, however, remains that the coinages emanate from the University environment and are suffuse with undergraduate culture that creates these social dialects for the entire community.This is the domain of socio-linguistics as the cultural and situational behavior of undergraduate users of the English language has drastically affected the coinages that get absorbed into the literary language adopted for the expression of thought and which as well has influenced the aesthetics of delivery in a very special way that is admirable as a unique form of expression. These modes of expression or coinages have, in some quarters, been described as “Africanization” of the English Language or in other cases as “Domestication”. This “Domestication” or “Africanization” as the case may be, seems to be what Achebe advocated when he posited that - The African writer should aim to use the language in a way that brings out his message best without altering the language to the extent that its value as a medium of International exchange will be lost. Again, some Scholars have chosen to describe this process as “Indigenization” of the English language. There are as such, outstanding writers like Chinue Achebe himself, Kofi Awoonor and Okot P’Bitek who have succinctly indigenized or domesticated the English language to their needs but their approaches differ somewhat from the student’s crass or offhand coinages that approximate to transliteration. What Achebe and others have done is to utilize African Oral expressions like proverbs which they effectively build into Standard English to enrich the English language further while the Student coinages entail allocation of different meanings to English words dictated by specific contextual use of the words and the introduction of words from African Traditional languages into English. Achebe’s usage is also different from what writers like Saro Wiwa, Ohaeto and Tomoloju attempted to achieve with language within their perceived socio-linguistic environments which is closer to the student’s coinages.Socio-linguistics as a discipline, we all know, studies the relationship between language and society; specifically why and how different social contexts determine the way we speak and how we relate to a cultural community. Socio-linguistics, therefore, deals with the actual way we use or generate language production in specific situations i.e. in Macro or large scale and Micro or small scale conversation analysis. It has to do with the study or analysis of talk interaction. We, therefore, have here adopted, to some extent, the method that has been described as the “Interactional Socio-linguistics method” to study the relationships between the different social classes of students and the kind of language they use as well as the motivation behind it. This method has also been described as “the social motivation of language change”.

4. Social Class Variation in Language Use

- Adopting this method provides an avenue to examine the social factors or constraints that determine language use in its contextual environment because, as we all observe, words are more functional in semantic contexts than at the lexical or phonological levels. Generally, it is easy to observe that students create their own words or “language” which they use to denote or describe certain actions and/or conditions prevalent in the campus environment but which creations soon permeate the social environment outside the academic that created them. This tendency is explainable from the fact that as humans, we tend to create or innovate in language either to satisfy an aesthetic need or simply to capture objects or ideas in a veiled manner that is not immediately intelligible to people outside our immediate interactional circle or social environment. As a socio-linguistic study, I have already defined our speech community to include the Universities of Calabar (UNICAL) and Cross River University of Technology (CRUTECH). Socio-linguistics defines a speech community as “a distinct group of people who use language in a unique and mutually acceptable way among themselves; sometimes referred to also as a “speech bund.” To be part of a particular speech bund or speech community, one must possess a certain degree of communicative competence to enable him interact intelligibly within that community which presupposes that those outside that speech community may find it difficult or even impossible to understand the meaning of the special codes or coinages members employ when communicating with each other. In this case, the speech community of UNICAL and CRUTECH students which we have identified for our study has developed slang or jargon which serves their special needs or priorities and also serves the immediate community outside the University as a result of constant interaction with students who live among them. Literary production, therefore, makes for interaction between artists and audiences, thus, creating a community of practice which allows for a socio-linguistic examination of the relationship between socialization, speech competence and identity. Examining language socialization among UNICAL and CRUTECH students provides us with a socio-linguistic community that thrives on the creation and maintenance of prestige which defines the identity of that community. Identity itself can be perceived of as a rather complex structure of relationships defining a group of say professionals, social groups or close knit families. Tertiary institutions which are mostly situated in Urban or cosmopolitan environments often times maintain a unique identity through language variation. This study, therefore, has attempted an analysis of these sources of variation as well as the motivation for them among this social class particularly as class and occupation have often been identified as very important linguistic markers in society. “Student Language” or “Student Dialect” can be considered as powerful in-group markers that express group pride and class solidarity as well as identity. In this vein, language is conceived of as a unique human ability, therefore, the ability to develop or create language for specific communication purposes and expression of cognitive experience is the most distinctive feature or attribute of human beings. For a language or linguistic expressions to be deemed as correct or appropriate by a particular audience; in this case students of the two Universities in Calabar; UNICAL and CRUTECH; the language must satisfy situational, contextual and a wide range of other social factors.We have, therefore, examined the ways by which language is realized and varies among this group depending on audience and the contexts of usage because even though we are all second language users of English as Nigerians, the type of dialect used by Individuals or social groups determines the class they belong to. Social class would, therefore, determine an individual’s pattern of linguistic variation and social class could be said to be more pervasive than geographical determinants of speech variation. In our area of study, however, social class is not denoted by the level of literacy or illiteracy since we are dealing with undergraduates who are supposedly literate or have acquired a certain level of ability to read and write. Here, social class is instead determined by age, gender, discipline or even life style. Life style in the sense that certain students are regarded as high class and some as low class in their social interactions, and their language will be mundane or ordinary. It is for this reason that Sandra Silberstein (2007) posits that - People use language as a tool to mark their identity and membership to certain social categories, for example, class, ethnicity, age and sex.The creation and maintenance of an identity could, however, be a conscious or unconscious act as reflected in their dressing or manner of speech since speech is more difficult to control and therefore more reflective of one’s identity.The development of several varieties of English is not surprising because the assumption of International acceptability and intelligibility is also consequent upon the proliferation of the language. Ekpe Brownson (2012) therefore, points out that - The present status of English as a global language has led to the proliferation of many varieties of English all over the world which according to Achebe (1965:29) is the price a world language…must pay in submission to many kinds of use. English as a global language has developed many varieties which differ from the “Standard” to the “Non-Standard” (P.43). It is, therefore, important to note at this point that in the Universities of Calabar (UNICAL) and Cross River University of Technology (CRUTECH), a Standard form of English is taught to all Students and is made compulsory for everyone and described as “English for Academic Purposes” (GSS 1101). In spite of this attempt to maintain a fairly uniform standard of English on campuses, several varieties still exist which answer to the leisure and other multi-dimensional needs of the students. It is these other forms of usage or coinages that I have analyzed in the attempt to decipher their suitability for consideration and adoption as Oral literary expressions that portray the African Literary environment in an acceptable and intelligible manner.

5. Socio-Linguistics and Literature

- Ebi Yeibo (2011) has aptly submitted that - As a result of the bilingual nature of African Nations, due to the historical accident of Colonialism, the problem of which language (i.e. indigenous or colonial language) to adopt for literary expression has lingered on.Furthermore, she asserts- Every literary text is constructed with language. Therefore it is imperative to determine how a particular writer has utilized the potentials of language to negotiate meaning(s) for his text.Perhaps we should note here, that it is not just a task for writers alone but that of the end users of the literature to determine which kind of language best explicates their aesthetic and moral or psychological and cultural milieu. It behooves all of us to examine the varieties of the languages at our disposal and to recommend one that best suits our needs and portrays our identity adequately. Given this scenario, it becomes imperative for us also to examine the varieties of English or linguistic coinages as they appear in our Tertiary institutions to determine their suitability and intelligibility for adoption as literary language. From this perspective, one must first make a distinction between standard use of language as is employed by the educated elite or upper classes of people e.g. University Lecturers, and Non-Standard usages as are employed in casual or leisure conversation by ordinary users or even the elite upper classes in less formal interactive contexts. It is in these non-standard contexts that we notice variations from standard usage that can be regarded as creative and suitable in the domain of Oral literature. For this reason, one advocates the adoption of these expressions for their graphic and/or expressive potential in the communication of ideas because these forms are easily understood by users in the immediate environment within which the Universities are situated and can serve as the language for literary creativity. Today, in Nigeria, there is no State that does not boast of a Tertiary institution, some of which operate multi-campuses in several Local Government Areas of the States. The result is that every nook and cranny of the Country has been penetrated by what can be described as “student or campus language,” a brand of linguistic expression peculiar to and serving the needs of students as they attempt to create an identity that distinguishes them from the larger society. In this vein, they create language that is unique to them but which is also expressive of the general ideological or psychological mindset of the society. Since these expressions do not remain within the confines of the Tertiary institution, they exist as language or extant modes of expression that define interaction in the general run of Nigerian public life. For this reason, and also because of their aesthetic and graphic potential for the vivification of experience and ideas, they can also be adopted for the expression of a literary ideology in the Nigerian society. They in-fact can serve as Oral literature in the modern context, thus, helping to debunk the erroneous impression that Oral literature is an ancient art form created in the past and handed down in a word fixed form. These creations represent the vibrant and dynamic nature of Oral literature as an art form that is continually being created and generated in our everyday lives and interactions, sometimes without out consciously being aware of it. This is the potential of Oral literature that endears it to Traditional African users of language in a colourful and creative manner even when serious subject is under discourse. The fluid nature of Oral literature allows for several manipulations or adjustments as embellishments that can reflect all shades of opinion and contextual variables. It, therefore, accommodates coinages whether old or new. This potential of Oral literature if properly harnessed can adequately enhance the creation of a truly African nay Nigerian literary identity within the present day context of globalization. After all K. Brooks (2010) has argued that “a writer does not write in an intellectual vacuum,” while Bronislaw Malinowski (1926) had earlier asserted that “language is about its immediate environment,” pre-supposing that both writer and speaker are influenced and so react to their environment in their communicative constructs. Speakers or creators of a language, therefore, provide writers with the linguistic and literary tools with which they create an identity for their society since social varieties exist because social systems work as an effective influence on identity formation.

6. Unical and Crutech Slangs as Oral Literature and Socio-Linguistic Units of Expression

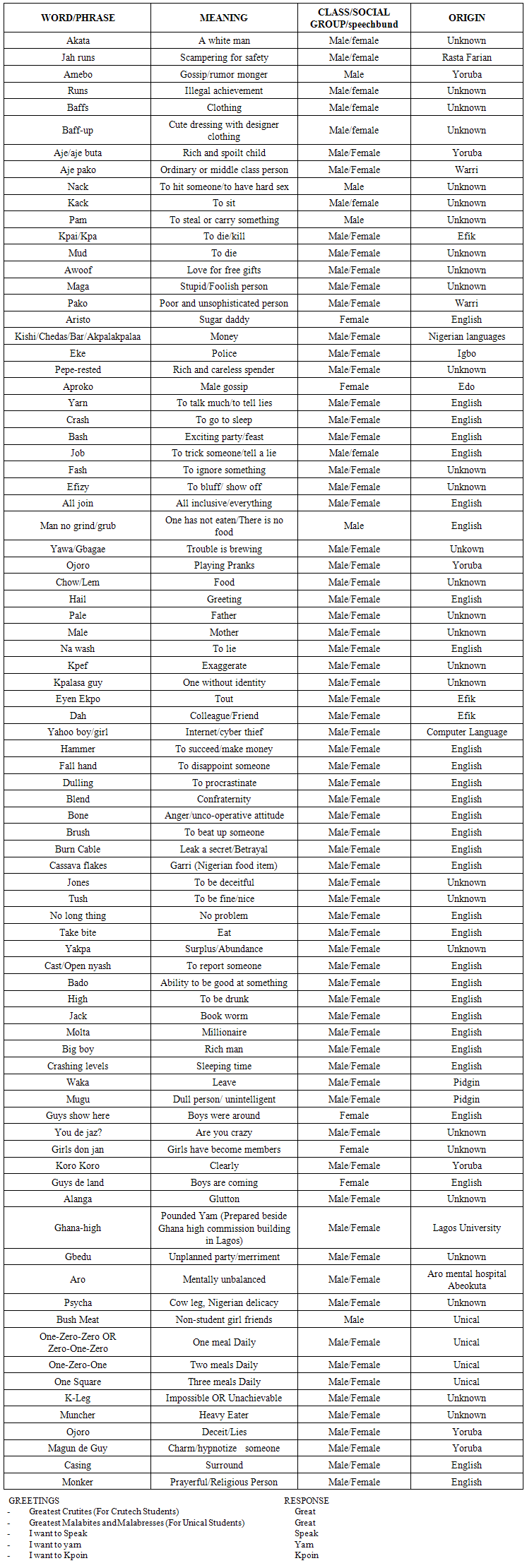

- Language can be viewed as any sound or utterance deliberately made to encode a message which can be intelligibly decoded to enhance communication between people operating within the same socio-linguistic environment and possessing the same linguistic capacity to interpret the coded messages. Using UNICAL and CRUTECH students as a case study, it is discovered that, between them, several coinages exist which are mutually intelligible and which they have introduced into their acquired English language vocabulary but with restricted meaning and understood mainly by them and those close to them. Some of these words are derived from the local Efik language where the two Universities are situated, while, others come from other Nigerian languages from where other students have come. What happens simply is that, a group of students coin or borrow a word and allocate to it a meaning dictated by particular situations or contexts. The meaning then spreads after several usages and gets adopted by other students and soon becomes a stock phrase amongst the student body. The creative turn to the word, however, depends on situational and contextual variables as well as the user’s artistic and creative skills at oratorical or linguistic manipulation. These words, Ebi Yeibo (2011) has described as constituting among others, coinages, borrowings, transfer of rhetorical devices from native languages, use of native similes and metaphors and use of culturally dependent speech styles. Others include transliterations and the use of syntactic devices and deviation. Most of what is in use here can, however, be classified simply as contextual meanings of lexical transliteration or semantic extension or shifts. A number of phrases or coinages and their meanings have here been collected to serve as examples used by different groups of male and female students which can also serve as identity markers for these groups. They are by no means exhaustive but could serve as a starting point for a wider socio-linguistic study of student language in Nigerian Universities. What is admirable about the use of these borrowed words or coinages is the easy blend with Standard English. Listeners easily decipher meanings within the context of use while themselves making further associations that expand knowledge and experience. The growth or prevalence of these coinages and borrowings is enhanced and facilitated by the fact that the University campus is a fertile breeding ground for all people; undergraduates and workers; of all classes and from different ethnic communities. Because of this diversity, Standard English usage becomes inadequate at all times particularly when interaction with junior workers is necessitated. This apart, even when students communicate among themselves, contextual or situational variables dictate choices of even the coined or borrowed words that will best portray a given context or situation. This, in itself requires creative application of the mind. Furthermore, Standard English itself sometimes becomes inadequate for the articulation of subtle nuances in certain operational contexts. The easiest way out for operators is therefore resort to coinages and borrowings that aptly describe such contexts in a condensed manner. Several words and phrases have, therefore, developed out of diverse interactional contexts to describe these peculiar situations. With time and continuous application, they become stock phrases though with restricted use and dependent on variations as the context demands. Bean and Dagen (2011) in their book titled Best Practices of Literacy Leaders: Keys to School Improvement posit that “Education underlies the struggle of all aboriginal communities to assert themselves and gain control over their lives in the present world of globalization. This, they argue, can only be achieved through consistent initiatives in language development and conservation. Perhaps the legacy that Nigerian Undergraduates can bequeath to their Nation is this contribution towards the development and sustenance of a unique dialect which will not only sustain them as a distinct class but also meet the needs of the larger society. Undergraduates as a literate group will therefore provide the leadership necessary for the proper functioning of a language policy that can sustain the progress of the dialect. The same Undergraduates can be seen as change agents to catalyze positive societal dispositions towards a consistent language policy that can maintain National identity.Joshua Fishman et al (2001) on their part posit that the present global dispensation tends to favour what can be described as a mono-cultural or mono-linguistic model which categorizes the world into modern or “civilized” and traditional or “primitive” peoples. In this context, the so-called traditional people and their languages are the endangered species. Michael Krauss (1995) therefore reports that only about 600 languages spoken today are assured of being around in the year 2100 which is about 10% of the present number of Oral languages.But a common language can evoke a sense of identity and continuity even in the midst of modern day existence where people of all races are brought together in a globalized system particularly in educational institutions. Skutnabb-Kangas et al (2009) in their own submission realize the inadequacy of training provided for children in most indigenous multi-lingual societies to enable them fit appropriately into required educational demands and to enable them succeed in school and out of school context. They therefore argue for the rights of any racial entity or group to develop a language that will maintain their identity. In a review of the book Social Justice through Multi-lingual Education, Devi, Vasanthi (2009) posits that “the book is also a powerful indictment of the sinister privileging of languages like English that are marginalizing and decimating humanities rich language resources. To this end, the development of “student language” in Nigerian Educational institutions is a welcome means of identity formation and maintenance not only within the University system but also in the larger Nigerian Society.The table below represents a cross-section of words and their meanings within the two institutions. These constitute the vocabulary of what can be described as “student language,” usage of which distinguishes it as a variety of English that creates a bond or close knit relationship between students in these two institutions.

7. Conclusions

- As can be seen from above, most of these expressions are distinct coinages that have little or no bearing with the English language while those derived from English have assumed meanings that are almost totally different from their original English meanings. The argument therefore, is that languages change with time, thus, giving birth to either varieties of the same language or producing other distinct languages through metamorphosis over a long period of time.Comparing the English spoken in Chaucer’s time to that of Shakespeare’s era and the modern period, one notices remarkable changes that can render a language almost unintelligible after several hundred years of its existence or each time it comes in contact with another language. What one posits here is that the infusion of these new phrases into English sentences used by students in their peculiar contexts creates grounds for a new brand of English or another language intelligible only to Nigerians since it has evolved from a Nigerian social setting or Nigerian environment.Furthermore, several Nigerian languages are equally prone to extinction. B. F. Grimes (2002) maintains that the number of Nigerian languages that have since gone into extinction stands at eight. Many more may follow as younger generations of Nigerians are fast losing touch with their traditional languages and becoming more proficient in English as their first language or L1 and these slangs as their second language or L2. Using slang as a second language thus, popularizes the vocabulary and opens it up to the wider society or social groups for more creative use.Offiong Ani Offiong and Stella Ansa (2003) have therefore observed that in the Cross River region some of the languages spoken like “Efut” and “Kion” are now extinct while Efik itself is highly threatened with the same fate. The other languages of Cross River State are not safe either unless there is concerted effort at their preservation which is very remote as there is no well co-ordinated policy aimed at the continuous development of these languages and our younger generations are getting more and more proficient in the use of slangs because of the heterogeneous nature of the environment they operate within. Slang becomes the easiest medium of communication not only among them but also outside the immediate confines of the University campuses. With the student population of UNICAL and CRUTECH ever on the increase, it is suspect that what will soon become the language of communication in the wider society in Calabar will neither be Efik nor any of the other Cross River languages. The future of this “student language” is as such very bright, given these antecedents. To this extent, Godwin Iwuchukwu (2006) also posits that - Linguists of the exoglosic school of thought…point to the inadequate vocabulary repertoire of most West African languages as media of instruction. This, he argues, accounts for the high degree of failure in external examinations particularly in the science based subjects which are taught in English that is sometimes incomprehensible to the students. Perhaps this inadequate vocabulary along with the problem of reduced comprehensibility of the English language, by extension, can also account for the development of slangs and coinages which students adopt in their attempt to expand their levels of communication and interaction. Consciously or unconsciously, we seem to be gradually edging towards the provision of a unique language of communication that may also answer to our social, literary and even administrative needs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML