-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

p-ISSN: 2326-0750 e-ISSN: 2326-0769

2014; 3(1): 9-16

doi:10.5923/j.linguistics.20140301.02

Phatic Communication: How English Native Speakers Create Ties of Union

Jumanto

Faculty of Cultural Studies, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, 50131, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Jumanto , Faculty of Cultural Studies, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, 50131, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This research article is about phatic communication among English native speakers, about how the native speakers create ties of union. The article is based on the writer’s elaborative qualitative research on Malinowski’s theory of phatic communion [1], Jakobson’s theory of language functions [2], and Brown and Gilman’s theory of power and solidarity [3]. The primary data are obtained from the interviews to nine native speakers with different dialects of American English, British English, and Australian English. The research findings show the functions of phatic communication among English native speakers and the types of expressions they use for creating ties of union. The phatic communication among English native speakers is then related to politeness and is also verified by other significant theories in verbal human communication.

Keywords: Language, Phatic communion, Function, Form, Expression, Politeness, Camaraderie, Communication, Power, Solidarity, Social distance

Cite this paper: Jumanto , Phatic Communication: How English Native Speakers Create Ties of Union, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 9-16. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20140301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

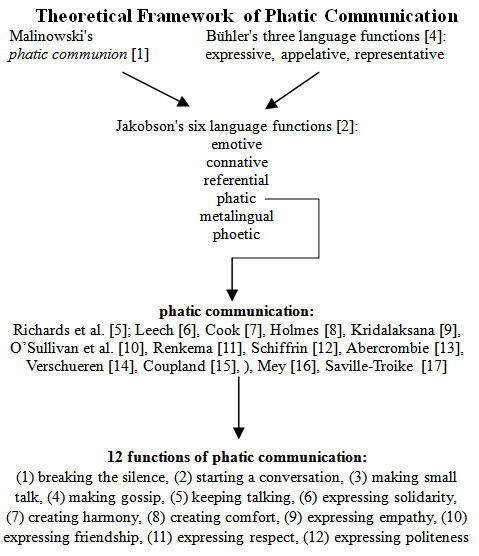

- Language use is, indeed, a social phenomenon. This has been best described by Malinowski [1] on his theory on language as a mode of action with the concept phatic communion as 'a type of speech in which ties of union are created by a mere exchange of words’ [1]. The concept of phatic communion is then elaborated by Jakobson [2] in the context of communication and is packed into the phatic function of language. The phatic function of language is one of Jakobson's six language functions, i.e. emotive, connative, referential, phatic, metalingual, and phoetic. The six functions are developed from Malinowski's theory of phatic communion and from Bühler's three language functions [4], i.e. expressive, appelative, and representative. According to Jakobson [2], the phatic function of language is the language function which stresses on the presence of contact between the sender (speaker) and the receiver (hearer) of the message. The term contact in Jakobson's theory is then referred to by Richards et al. [5] as social contact in their definition on phatic communion, i.e. communication between people which is not intended to seek or convey information but has the social function for establishing or maintaining social contact. In its further development, Malinowski's concept of phatic communion [1] or Jakobson's phatic function of language [2] is often referred to by linguists when taking into accounts for phatic communication. The linguists whose accounts are involved in this research are Leech [6], Cook [7], Holmes [8], Kridalaksana [9], O’Sullivan et al. [10], Renkema [11], Schiffrin [12], Abercrombie [13], Verschueren [14], Coupland [15], Mey [16], and Saville-Troike [17]. The accounts of the linguists are, in this research, then packed into twelve functions of phatic communication, the theoretical framework of which is outlined in the following chart1:

The operational definition proposed in this research is that phatic communication is a verbal communication between a speaker and a hearer to maintain the social relationship between them, not to give an emphasis on information content of the communication. The maintenance of the social relationship between the speaker and the hearer is carried out by breaking the silence, starting a conversation, making small talk, making gossip, keeping talking, expressing solidarity, creating harmony, creating comfort, expressing empathy, expressing friendship, expressing respect, and expressing politeness. This research is aimed at exploring phatic communication among English native speakers, particularly on how the native speakers exchange words to create ties of union. This exploration is trying to discover functions and forms of the social interaction based on the social contact. Besides, it is important to also find out the influences of the factors of power and solidarity and of informal and formal situations on phatic communication among English native speakers, as well as the relationship between phatic communication and linguistic politeness among English native speakers.

The operational definition proposed in this research is that phatic communication is a verbal communication between a speaker and a hearer to maintain the social relationship between them, not to give an emphasis on information content of the communication. The maintenance of the social relationship between the speaker and the hearer is carried out by breaking the silence, starting a conversation, making small talk, making gossip, keeping talking, expressing solidarity, creating harmony, creating comfort, expressing empathy, expressing friendship, expressing respect, and expressing politeness. This research is aimed at exploring phatic communication among English native speakers, particularly on how the native speakers exchange words to create ties of union. This exploration is trying to discover functions and forms of the social interaction based on the social contact. Besides, it is important to also find out the influences of the factors of power and solidarity and of informal and formal situations on phatic communication among English native speakers, as well as the relationship between phatic communication and linguistic politeness among English native speakers.2. Research Methodology

- This research is empirical, qualitative, and synchronic in nature. This research is empirical and qualitative in the sense that it studies the data or the corpuses directly obtained by interviewing the informants, and the research data are of verbal signs, not of figures or numbers. This qualitative reseach focuses on the emic perspective, i.e. viewpoints, perceptions, meanings, and interpretations given by the informants [18]. Thus, this qualitative research seeks for meanings, to see the world from the viewpoints of the subjects under research [19], [20]. This research is also synchronic in nature in the sense that it is not aimed at studying phatic communication among English antive speakers from time to time. This qualitative research involves the three components proposed by Strauss and Corbin [21], i.e. interview to get the data, coding as an analytic and interpretive procedure, and a review of research findings or in-depth discussions as a written verbal report. Meanwhile, the methods employed in this research are interview, transcript, and textual analysis [20].The research informants are English native speakers. Among the varieties of English in the world, the three biggest varieties are taken: American English, British English, and Australian English. From the three varieties, nine informants are selected for this research, i.e. three with different dialects are selected for each of American English and British English, and the other three informants from different territories are selected for Australian English. The selection of the informants are done by considering the requirements for being informants as proposed by Samarin [22], the factors of which include age, cultural knowledge, psychological quality, interest and concern, and language skills of the informants. The data collection in this research is carried out through an in-depth interview and an exploration method. The in-depth interview in this research is of formal and semi-structured type so that the interview can be more focused with some prepared agenda (questionnaires/an interview guide). Through this method the so-called dross rate can be avoided. The in-depth interview about phatic communication among English native speakers involves the twelve functions of phatic communication proposed. Each function in the interview is varied with prompts – some leading and more specific, short questions [18], which are constructed based on logical, empirical considerations on specific communicative functions to support the twelve functions of phatic communication proposed in this research. The informants' responses on the prompts are later elaborated to build the twelve functions of phatic communication. The twelve functions of phatic communication elaborated in the interview are then linked to communicative situations with four types of hearer different in the factors of power and solidarity according to Brown dan Gilman [3], namely (1) a close superior (superior and solidary), (2) a not close superior (superior and not solidary), (3) a close subordinate (inferior and solidary), and (4) a not close subordinate (inferior and not solidary). Preparation for the interview is done before and the interview is recorded. The results of the interview are used as the primary data of the research. Meanwhile, the exploration method is used for collecting material or data from other written sources, such as English textbooks or reference books, including conversation texts. The material or the data obtained from other written sources are used as the secondary data of the research and are later employed in the triangulation process. Validity and reliability are also taken into account in this research. Validity is the truth value of a research, which is to measure what should be measured [18]. The validity of this research is of two types, internal and external. The internal validity refers to the researcher's report on realities of the informants' opinions in form of coherent writings and parts of the interview. The external validity refers to the generalisability of this research which is applicable to similar other situations. This is satisfied by a thick description provided in this research so that other researchers are equipped enough to give judgements. Other validities applied in this research include the elements of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, as proposed by Lincoln and Guba [23] and Holloway [18]. On the other side, the reliability or authenticity of this research includes the components of fairness, ontological authenticity, educative authenticity, catalytic authenticity, and tactical authenticity, as proposed by Lincoln and Guba [23]. The data analyses are done through a coding technique. Coding in the qualitative research means identifying and labeling concepts and phrases in the interview transcript and field records [18], or in brief, a process of data analyses [21]. Coding is carried out through three steps, i.e. open coding, axial coding, selective coding [21], [18]. Open coding is a process to separate and conceptualize data. Axial coding is a process to reunite the separated data in the open coding to build major categories. Selective coding is then used to discover the main phenomena, i.e. the core categories or the core variables, which relate all existing categories [18], or the central phenomena which unite all the other categories [21]. The core categories function as a thread which unites and produces a line of story. In this phase, the researcher opens the research main points and unites all elements from the emerging theories. The core categories consist of most significant ideas for the participants [18]. Upon the completion of the coding process, the data are then analyzed by using the interpretation method with theoretically critical and empirically logical assumptions. Related literature or other related books have also become sources of data which are used for confirmation or refutation [18]. The researcher has tried to relate this research to other researchers’ works, and sought to find out their relevance with the research findings. The researcher then provides explanations or discussions on the research findings in a synthesis.

3. Twelve Functions for Creating Ties of Union

- In general, based on the research findings, English native speakers create ties of union or a good social relationship by using 12 functions of phatic communication, i.e. (1) breaking the silence, (2) starting a conversation, (3) making small talk, (4) making gossip, (5) keeping talking, (6) expressing solidarity, (7) creating harmony, (8) creating comfort, (9) expressing empathy, (10) expressing friendship, (11) expressing respect, and (12) expressing politeness, to hearers with different aspects of power and solidarity, and in different situations, informal or formal. In particular, the research on the 12 functions of phatic communication among English native speakers in line with different hearers and different situations, shows the findings as follows: (1) Breaking the silence is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by greeting, by mentioning names, titles, or titles and names, or by saying goodbye in informal or formal situations. Meanwhile, breaking the silence by commenting on something obvious is done by the native speakers to close superiors or subordinates, but not to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (2) Starting a conversation is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by greeting or by interrupting in informal or formal situations. Meanwhile, starting a conversation by mentioning names, titles, or titles and names is done by the native speakers to superiors. This is also done to not close subordinates, and sometimes to close subordinates. Starting a conversation by commenting on something obvious or by apologizing is done by the native speakers to close superiors or subordinates. This is sometimes done to not close superiors. (3) Making small talk is done by English native speakers to close superiors or subordinates in informal or formal situations. This is sometimes also done to not close superiors. English native speakers start and end the small talk to close superiors and subordinates. They do not start the small talk to not close superiors, but they sometimes end the small talk. (4) Making gossip is done by English native speakers to close superiors in informal situations in the absence of someone else within the hearing distance. However, they sometimes do this to close subordinates. English native speakers sometimes start the gossip and sometimes also end it.(5) Keeping talking or keeping the conversation going is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by avoiding silence when talking, by changing the topic of conversation, or by expressing listening noises, in informal or formal situations. Keeping the conversation going by interrupting is done by the native speakers only to close hearers and not close subordinates, not to not close superiors.(6) Expressing solidarity is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by expressing wishes, by congratulating, by agreeing on something, by apologizing, or by thanking, in informal or formal situations. (7) Creating harmony is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by congratulating, by agreeing on something, by apologizing, by thanking, or by joking in informal or formal situations. (8) Creating comfort is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by agreeing on something, by apologizing, or by thanking, in informal or formal situations. (9) Expressing empathy is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by encouraging, by expressing wishes, by congratulating, by agreeing on something, by apologizing, by thanking, or by expressing sympathy, in informal or formal situations. (10) Expressing friendship is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by expressing wishes, by congratulating, by agreeing on something, by apologizing, by thanking, by giving compliments, by joking, or by encouraging, in informal or formal situations. (11) Expressing respect is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by expressing wishes, by congratulating, by agreeing on something, by apologizing, by thanking, or by expressing sympathy, in informal or formal situations. (12) Expressing politeness is done by English native speakers to superiors or subordinates by breaking the silence, by starting a conversation, by making small talk, by keeping talking, by expressing solidarity, by creating harmony, by creating comfort, by expressing empathy, by expressing friendship, and by expressing respect, in informal or formal situations, but not by making gossip. The research findings also show that particular communicative functions are used to express some functions of phatic communication in line with different hearers and different situations, as follows: (a) Expressing wishes is done by English native speakers for creating harmony or for creating comfort to close superiors or subordinates, and sometimes to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (b) Giving compliments is done by English native speakers for expressing solidarity, for creating harmony, for creating comfort, for expressing empathy, or for expressing respect to close superiors or subordinates, but sometimes, or never at all, to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (c) Criticizing indirectly is done by English native speakers for expressing solidarity, for creating harmony, for expressing empathy, for expressing friendship, or for expressing respect to not close superiors or subordinates, but not to close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (d) Pacifyng is done by English native speakers for creating comfort, for expressing empathy, for expressing friendship, or for expressing respect to close superiors or subordinates, but sometimes, or never at all, to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (e) Encouraging is done by English native speakers for creating comfort or for expressing respect to close superiors or subordinates, and sometimes to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (f) Expressing sympathy is done by English native speakers for expressing friendship to close superiors or subordinates, and sometimes to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. (g) Saying bad words is done by English native speakers for expressing solidarity, for creating harmony, for creating comfort, for expressing empathy, or for expressing friendship to close superiors, not to other hearers, in informal situations, in the absence of someone else. However, Englsih native speakers sometimes also say bad words for expressing friendship to close subordinates, in informal situations, in the absence of someone else. (h) Mocking is done by English native speakers for expressing solidarity or for expressing friendship to close superiors, not to other hearers, in informal situations, in the absence of someone else. (i) Joking is done by English native speakers for expressing solidarity, for creating comfort, or for expressing empathy to close superiors or subordinates, and sometimes, or never at all, to not close superiors, in informal or formal situations. However, joking for expressing respect is sometimes done by English native speakers to not close superiors or subordinates, but not to close superiors, in informal or formal situations.

4. Types of Expressions for Creating Ties of Union

- Based on the research findings, English native speakers exchange expressions to serve the 12 functions of phatic communication discussed above. The findings show that the expressions of phatic communication among English native speakers in line with different hearers and different situations are as follows: (1) For breaking the silence, English native speakers use similar types of expressions in informal and formal situations. However, the native speakers use shorter and informal expressions when speaking to close hearers, and longer and formal expressions when speaking to not close hearers. Greeting: e.g. ‘Hi!’, ‘Hello!’, ‘Hello. How are you?’ mentioning names, titles, or titles and names:e.g. ‘Mike!’, “Doctor!’, ‘Mr. Langford!’, ‘Doctor Peter!’Saying goodbye: e.g. ‘Bye!’, ‘Goodbye!’, ‘Excuse me. I have to go now.’Commenting on something obvious: e.g. ‘Hi. You’re busy!’, ‘Oh, it’s hot today!’‘Oh, you are going on the new shirt!’, ‘Oh, look atthe rain, pouring down really hard!’ (2) For starting a conversation, English native speakers use similar types of expressions in informal and formal situations. However, in formal situations, the native speakers sometimes use longer and formal expressions for starting a conversation to superiors and not close subordinates. Interrupting: e.g. ‘Excuse me!’, ‘Excuse me. Can I borrow your time for a minute?’Apologizing: e.g. ‘Hey, I need you to sign. Sorry!, or ‘I’m sorry for being late…. I must apologize.’ (3) For making small talk, English native speakers use similar types of expressions in informal and formal situations. However, in formal situations, the native speakers sometimes use longer and formal expressions for making small talk to close superiors. English native speakers make small talk in form of conversations, which consists of three structures: (a) Starting the small talk, i.e. by greeting, e.g. ‘Morning!’ or ‘How are you?’, by commenting on something obvious, e.g. ‘It’s a nice day, isn’t it?’, or a variant of it, e.g. ‘Hi! How are you today?’;(b) Making the small talk, i.e. by developing the conversations based on various topics dependent on the intention of the speaker and hearer, about family, holiday, weekend, TV program, mutual friends, work, school, weather, etc., i.e. by asking a question ‘How is your family?’, ‘How was your holiday?’, ‘Did you have a pleasant weekend?’, etc. The small talk is of common, safe, and polite topics, not personal or private, or not of touchy topics; and (c) Ending the small talk, i.e. by apologizing and giving an excuse, e.g. ‘I am sorry. I have to go now’, by saying goodbye, e.g. ‘Goodbye for now!’, by making a promise or a wish to meet again, e.g. ‘See you later!’, or a variant of it, e.g. ‘Hey, see you! I have to get back to work. I got to do something else’.(4) For making gossip, English native speakers use free and informal expressions. The native speakers make gossip only in informal situations, in the absence of someone else. Just like making small talk, English native speakers make gossip in form of conversations, which also consists of three structures: (a) Starting the gossip, i.e. by giving a statement, e.g. ‘Oh, I met so and so last week …’, by asking a question, e.g. ‘Have they broken up yet? Is she pregnant?’, or a variant of it, e.g. ‘Did you hear about …? Wanna tell me? I only heard this. I don’t know if it’s true’;(b) Making the gossip, i.e. by developing the conversations based on various topics in the statements or questions above about mutual friends, office friends, office superiors, public figures, politicians, etc., those of someone else. The gossip is of any topics, probably including touchy topics, i.e. salary, price of belongings, age, politics, religious practices, status of marriage, a couple without children, etc., or even dangerous topics, i.e. politics, religions, races; and (c) Ending the gossip, i.e. by giving an excuse or by changing the topic of conversation, e.g. ‘Goodbye. I have to get back to work’ or ‘So, how is school these days?’. (5) For keeping talking or keeping the conversation going, English native speakers use similar types of expressions in informal and formal situations, except to not close superiors. In formal situations, the native speakers use longer and formal expressions for keeping the conversation going to not close superiors. Avoiding silence when talking: e.g. ‘Ehm’, ‘Well’, ‘Let me see’, ‘What’s that thing?’Changing the topic of conversation: e.g. ‘Oh’, ‘Say’, ‘By the way, ….’, ‘I’ve been meaning to talk to you about….’Expressing listening noises: e.g. ‘Ehm’, ‘Aha’, ‘Really?’, ‘Oh, is that so?’, ‘I understand’ (6) For expressing solidarity, for creating harmony, for creating comfort, for expressing empathy, for expressing friendship, and for expressing respect in formal situations, English native speakers use longer, more complete, formal, and careful expressions, especially in the selection of appropriate vocabulary items, to close superiors, and sometimes to not close superiors. The native speakers use careful expressions, with appropriate vocabulary items, especially for creating comfort, for expressing empathy, and for expressing respect to superiors in formal situations. Expressing wishes: e.g. ‘Good luck!’, ‘I hope that goes well’, ‘I hope that the situation works out well’Congratulating: e.g. ‘Congratulations!’, ‘Congratulations on the good piece of work!’, ‘Congratulation for having production meet the quota for the month’Agreeing on something: e.g. ‘Yes, exactly!’, ‘Definitely!’, ‘I agree with you’, ‘I understand your point’, ‘Yes, you are right’, ‘I think that’s a good idea’, ‘I couldn’t agree more’ Apologizing: e.g. ‘I am sorry’, ‘I’m sorry. I’m messed up’, ‘If I’m wrong, I’m sorry’, ‘I apologize that I was taking the wrong way, I said the wrong thing’ Thanking: e.g. ‘Oh, thanks!’, ‘Thanks for your help’, ‘Thank you for….. I appreciate it’, ‘Thank you. I really appreciate your doing that’Giving compliments: e.g. ‘Great job!’, ‘Well done!’, ‘Nice tie!’, ‘ I think you did the right thing’, ‘I think you handled the situation very well’, ‘Well, I like the way you did that. It was very good’, ‘Congratulations. I really thought that speech was effective’Criticizing indirectly: e.g. ‘I don’t agree with this. I want to change it’, ‘I think it would be better if we did this’, ‘Well, I understand what you are trying to say, I don’t agree with you. Perhaps, there’s another way to look at this’Saying bad words: e.g. ‘Bleeding’, ‘Oh, those bloody idiots!’, ‘Fucking useless! Did you see that game last night?’, Didn’t you think that latest message we got from….was bloody stupid?’ Saying bad words: e.g. ‘Bleeding’, ‘Oh, those bloody idiots!’, ‘Fucking useless! Did you see that game last night?’, Didn’t you think that latest message we got from….was bloody stupid?’ Mocking:e.g. ‘Since you don’t have anything else to do today, I want to come and bug you for a minute!’, ‘Oh, nice piece of driving! Michael Schumaker, yeah?’, ‘Ah, you never get the job! You are terrible!’Joking:e.g. ‘Hey, since you don’t have enough to do, I’m going to give you some work!’, ‘Is that an executive decion?’ (7) For making small talk and for making gossip, English native speakers use form of conversations with the same structures, i.e. (a) starting the conversation, (b) making the conversation, and (c) ending the conversation, but with reference to different contexts. The different contexts include different types of hearer and different topics of conversation, as have been accounted for above.

5. Phatic Communication and Politeness

- The research findings show that the relationship between phatic communication among English native speakers and linguistic politeness is reflected in indicators below:(1) Phatic communication among English native speakers is used for expressing politeness (maintaining the social distance), for expressing politeness and friendship (shortening the social distance), and for expressing friendship (eliminating the social distance) to different hearers in the factors of power and solidarity. (2) Phatic communication among English native speakers is of negative politeness strategies (strategies of impersonality), showing the social distance between the speaker and hearer, and of positive politeness strategies (strategies of informality), showing the closeness between the speaker and hearer [24], [25]. Phatic communication among English native speakers is strategies of deference or strategies of emotive communication to show interpersonal supportiveness by interpersonally supportive delivery of messages to avoid interpersonal conflicts [26]. Phatic communication among English native speakers is of volitional strategies, i.e. the active selection from the speaker’s will in the open communication system which is dynamic and is oriented to different hearers in the factors of power and solidarity [27].

6. Verification by Other Theories

- The research findings on phatic communication among English native speakers in line with other theories show significant relevance as follows: (1) Phatic communication among English native speakers is in line with the theory of language as human acts, the theory of language functions, and the theory of face-to-face communication. In the theory of language as human acts, phatic communication among English native speakers is in line with Malinowski’s theory [1] that language is a unity of human activities, a mode of action, and a phatic communion. In the theory of language functions, phatic communication among English native speakers is also in line with Bühler’s theory [4] on expressive and appelative functions of language, Jakobson’s theory [2] on phatic function of language, and Halliday’s theory [28] on interpersonal function of language. In the theory of face-to-face communication, phatic communication among English native speakers is also in line with the theory of Johari Window. Phatic communication among English native speakers to close hearers represents the first quadrant or the open quadrant of Johari Window, whereas phatic communication to not close hearers represents the third quadrant or the hidden quadrant of the theory [29]. (2) In the theory of language and culture, phatic communication among English native speakers is a sociocultural reality which contains social conventions and norms in the speech society of English native speakers and – also in line with the theory of language relativity – which is relatively different from other speech societies [30], [31], [32]. (3) In the theory of communicative competence, phatic communication among English native speakers is part of communicative competence in the self of English native speakers. Communicative competence includes linguistic competence, sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence, strategic competence, pragmatic competence, and cultural competence [33], [34]. (4) In the theory of text and context, phatic communication among English native speakers is a discourse, consisting of text and context. The text of the phatic communication is various expressions which are used to serve the 12 functions of phatic communication in the research, whereas the context of the phatic communication is different communicative functions, different hearers, and also different situations. The text of the phatic communication is bound to the context of the phatic communication [16].

7. Conclusions

- This research on phatic communication among English native speakers is far from being perfect [35], [36]. Other important findings are probably not yet revealed. Several points to bring to an end are presented as follows: (1) A further research on phatic communication among English native speakers which involves close equal hearers and not close equal hearers of Brown and Gilman’s theory (1968) can be carried out as a follow-up or a complement to this research; (2) Field observations on phatic communication among English native speakers can be conducted to verify or to test some of or all of the findings of this research; (3) The results of this research on phatic communication among English native speakers can be used as guidelines for English language learners to create and as well as to maintain a good social relationship with English native speakers they meet or deal with so that the efforts can support their further verbal communication with the native speakers;(4) The results of this research on phatic communication among English native speakers can be applied by English teachers in the teaching and learning process with their English students so that the students will be able to communicate well in English according to the context and situation and to avoid the so-called cross-cultural misunderstanding; (5) This research model on phatic communication among English native speakers can be employed by linguistic researchers to conduct researches on phatic communication among native speakers of other languages in the world; (6) The results of this research on phatic communication among English native speakers can be utilized by communication science researchers as guidelines for conducting a further research on the combination of phatic communication (as part of verbal communication) and non-verbal communication among the native speakers of a particular speech society. (7) The results of this research on phatic communication among English native speakers can be used as part of library collection in language institutions so that it can function as a reference for learners, teachers, and researchers in the institutions.

ACKOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to acknowledge the distinguished nine English native speakers here for contributing their thoughts as well as precious opinions to the linguistic world that I have lived in and that I have tried the best efforts to develop. The nine English native speakers are: Samantha Custer (New England, US), John Custer (Pennsylvania, US), Bradford Sincock (Michigan, US), Patricia Mary O’Dwyer (South Ireland, GB), Patrick Bradley (Scotland, GB), Simon Colledge (London, UK, GB), Ian Briggs (Northern Territory, Australia), Anastasia de Guise (New South Wales, Australia), and Katrina Michelle Langford (Victoria, Australia). They have inspired me on how a linguist should perform in the linguistic world as well as on how I should learn more to observe people talking and to get real-life lessons for developing the pragmatic world. May God the Almighty always be with and bless you all. I am looking forward to seeing you again somehow, somewhere, someday. JumantoA PhD Graduate, University of Indonesia, Jakarta, 2006A Senior Lecturer, University of Dian Nuswantoro, Semarang, 2014

Note

- 1. This chart is also developed from the one proposed by Kridalaksana [9].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML