-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

p-ISSN: 2326-0750 e-ISSN: 2326-0769

2013; 2(4): 45-53

doi:10.5923/j.linguistics.20130204.01

Bi-directional Development of L2 Suprasegmentals

Seokhan Kang

Department of English Language Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, 151-742, South Korea

Correspondence to: Seokhan Kang, Department of English Language Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, 151-742, South Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study investigated bi-directional development of L2 suprasegmentals when second language learners acquire L2. L2 speech of native Korean and English speakers with various length of immersion was compared and analyzed. It was expected that the longer immersed L2 learners would have suprasegmental features more similar to native L1 speakers compared with the shorter immersed learners, while the variation in L2 acquisition could be extended by the effect of background language. Both experiments for Korean learners of English and English learners of Korean were carried out to check the hypothesis. The results showed that L2 longer-immersed groups exerted the similar features of L1 native speakers. The direction of L2 development, however, was different. As a result, both groups have features with similar and different patterns at the same time. The similar features are realized in temporal features, while the contrastive features are found in the spectral cues. The result suggests that L2 development is determined by both factors: L1 background language and universal L2 developmental patterns.

Keywords: Second Language Acquisition, Immersion, Bi-direction, F0, Speech Rate, Boundary Cues, Prosody, Phonetics

Cite this paper: Seokhan Kang, Bi-directional Development of L2 Suprasegmentals, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 2 No. 4, 2013, pp. 45-53. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20130204.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The suprasegmental features of an L2 (a second language) are considered to be major factors in pronouncing a fluent L2 speech. Indeed, the L2 fluency acquisition might be impacted by suprasegmental factors[1][2]. The degree of L2 suprasegmental acquisition, however, is determined by key subject factors, such as the L1 background and L2 levels of experience. The aim of the study is to investigate how the effect of L2 immersion has influence on acquiring L2 suprasegmentals. For this investigation, parallel influences of the L1 on the L2 and L2 on the L1 were examined in production.A number of studies investigating the acquisition of a second language have focused on what suprasegmental factors affect the L2 acquisition. The features that researchers have found to be significant in fluency include speaking rate[3], pause structure[1], peak alignment[2], F0 range[4], and intonation[5]. The features involved in L2 fluent acquisition are closely tied to temporal and spectral cues. Temporal aspects dominating features in fluency judgment refer to durational features including speech rate, articulation rate, pause duration, and frequency. Along with temporal factors, spectral features such as pitch range, peak alignment, stress, and intonation determine the L2 fluency. For example, improper pitch contour, narrow pitch range, and tones in the mid of phrases, lead to foreign-like pronunciation. These studies clearly support the argument that some spectral features contribute more to the overall perception of fluency.These L2 suprasegmental features are affected by various factors: the age[6], language experience[2][4][5], the background of the native language[7], and motivation[8]. Out of various effects, it is well-known that the effect of immersion experience has been suggested to play a key role in native-like prosodic production[5]. For example, Ueyama and Jun (1997) observed how a certain aspect of prosody is acquired in a second language. They observed productions of a rising and falling intonation pattern in English by native Korean learners of English differ by following the levels of proficiency. Their study suggests that less proficient speakers of an L2 rely on the prosodic structure of the L1 when producing a similar prosodic contrast in the L2. Moreover, with experience in the target language, a similar prosodic structure is acquired as indicated by productions of more proficient Korean speakers. They assume that English intonation patterns might be difficult for Korean speakers to acquire correctly because of the similar structure of prosody between L1 and L2.In spite of accumulating research in L2 acquisition, authentic understanding on L2 acquisition is quite hard to be caught up because most studies have focused on uni-directional L2 acquisition which may lead to the biased understanding[4][5]. This study is based on the reflection that comparatively rare works have been carried out in bi-directional development of suprasegmental for both L1 and L2. The study examines the comparison between English as L1 and L2 versus Korean as L1 and L2 with different length of immersion experience on L2 acquisition.

2. Suprasegmental Features of Korean and English

- As a universal linguistic feature, there is a general tendency for F0 to begin on a moderate frequency, move to a higher frequency, and then lower across the sentence. The intonation of most languages can be characterized by the declination theory, in which the declining F0 that gradually falls throughout the course of a sentence represents a linguistically salient aspect of the F0 contour. Declination is found in English, Dutch, French, Japanese, and Finnish[9].The degree and type of the F0 movement, however, may vary by languages and linguistic structures which are affected by the type of suprasegmental structures they possess. Korean has a different prosody structure from English. Korean has two prosodic units above the prosodic word: the intonational phrase (IP) and the accentual phrase (AP)[10]. An IP is defined by phrase final lengthening as the form of a boundary tone and also is the highest prosodic unit defined by intonation, including one or more APs. An IP boundary tone has a falling F0 pattern in declarative sentences. APs in Korean do not have any pitch accents associated with stressed syllables in their domain and also lack the phrase accent which occurs at the end of the intermediate phrase of English. APs are associated with tonal patterns; the basic type being LHLH, though 15 tonal patterns have been described, based on the number of syllables and segmental make-up of the AP1. In Korean, however, it is difficult to find the distinctive declination tilt because the narrow pitch in an IP-final part is not applied. Since there is only one accented syllable usually in the IP-final syllable, this makes it hard to form a top-line. English, unlike Korean, is a stress language in which one syllable is stressed within the prosodic foot. The stressed syllable tends to have a greater duration, higher pitch, and more complicated contour of F0 than the unstressed syllables and serves as the syllable on which pitch accents are realized. English has three prosodic units above the prosodic foot: the intonation phrase (IP), the intermediate phrase (iP), and accentual group (AG)[11]. An IP is the highest prosodic unit defined by intonation and may contain one or more iPs. It has final lengthening with the final falling F0 in the case of declarative sentences. An iP has to contain at least one pitch accent with either falling or rising F0. Each iP consists of one or more AGs, defined as the domain for a pitch accent configuration. Also AGs contain one or more Feet, each of which comprises a strong initial syllable and following weak syllables. The L1 suprasegmental structure has some influences on L2 intelligible speaking. Jilka (2000) reported that German/American bilinguals used a wider range of pitch in their American English than in German. The F0 declination patterns are also affected by phrase types. The English IP has a falling F0 contour as a terminal or final signal, while the iP, as a non-terminal or continuity signal, has various patterns of F0 contour: LHL, HLL, HL, LL, LLH, H, L, etc. Lieberman (1967) suggested that variation could be found in the non-terminal part of the fundamental frequency contour, in that the lower unit of the iP might have various F0 contours different from higher units of the IP. This implies that such difference is due to the intonational differences depending on terminal or non-terminal sentences.The current study investigates L2 suprasegmental acquisition by the mixed influence of background language and the length of immersion, to the target language. The goal of the study is to extend our understanding of factors influencing the acquisition of suprasegmentals, which affects the fluency of L2 speech. In the experiment, the L2 suprasegmental production for the mutual effects was acoustically examined. For the investigation, six experimental groups – native English learners of Korean with two different levels (short and long immersed group), and native Korean learners of English with two different levels, and both native Australian English and Korean speakers (as control groups) – took part in the experiment.Experiments checked the hypothesis that L2 learners with longer length of immersion tend to produce L2 suprasegmentals closer to native speakers. Acoustic analysis of L2 suprasegmental production was carried out focusing on to what extent the features of the acoustic cues change over both effects of L1 and the length of immersion. Four suprasegmental cues (F0 range, speech rate, and syllable duration and mean F0 in the boundary), which proved to be the most important cues to determine the L2 fluency ratings[2][4] were investigated.As previous research reported, in terms of whether native-like suprasegmental production was or was not observed for both L1 groups with different lengths of immersion, this paper sought to add to the body of scientific knowledge and determine whether the effect of L1 and L2 would affect the suprasegmental production over the different length of immersion. In addition to examining the mutual factors of L1 and immersion, the study also investigated whether there were any interactions between mutual effects and the suprasegmental phonetic cues in the experiment.The study examined the hypothesis that L2 prosody for adult learners could change over the length of immersion through interaction with the L1. More specifically, if the adult learners whose duration of immersion gets longer and longer, it might have benefitted from some specified suprasegmental cues which the immersion triggers. The overall goal of this investigation is to examine how the various prosodic features from L1 actually follow the way both native Korean and English speakers produce native speech.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

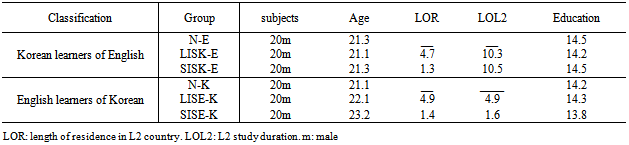

- The data were collected from 120 adult participants for two experiments. None reported being diagnosed with a language or speech disorder. In the first experiment, the participants for L2 learners were divided into three groups of 20 each: LISK-E (Long Immersed Speakers of Koreans learning English); SISK-E (Short-Immersed Speakers of Koreans learning English); and native English speakers as a control group. For the second experiment, the participants for L2 English learners of Korean were divided into three groups of 20 each: LISE-K (Long Immersed Speakers of English natives learning Korean); SISE-K (Short-Immersed Speakers of English natives learning Korean; and N-K (Native Korean Speakers); and native Korean speakers as a control group.The characteristics of participants in the six groups are presented in Table 1. Most of the Korean learners of English were visiting or enrolled students at universities in North America. The Korean learners of English in both groups had begun learning English in their home country, South Korea, starting from 3rd grade of the public elementary schools. The Korean LISK-E subjects were selected based on years of immersion experience in Australia over 3 years (mean 4.7 years), while SISE-K participants were less than 3 years (mean 1.3 years).On the contrary, L2 Korean English learners were visiting-students or English instructors who joined Korean Language program at the Language Center in Seoul National University. Most of all were from North America to learn Korean for business, study, or personal matters (e.g., marriage). The LISE-K English subjects were selected based on years of immersion experience over 3 years (mean 4.9 years), while SISE-K participants were less than 3 years (mean 1.4 years). Table 1 presents participants’ information including age, the number of years they had studied L2 (English or Korean), and the number of years they spent in L2 speaking countries.

3.2. Materials and Procedures

- The scripts were presented to participants over a loudspeaker using a laptop computer in question - answer-question sequences (Appendix). A delay of around ten seconds was provided after the second question in each sequence, allowing some time for the production of the target sentences. It was intended to avoid the direct imitation from the sensory memory (e.g., Flege and Fletcher, 1992; Flege, 2006). The sequences were presented randomly. The elicitation of the second repetition was analyzed. Before they produced the sentences, it was confirmed that they knew what the sentences meant, and that they knew how to pronounce them.Each experiment was conducted separately. Each participant was asked to produce each L2 (English or Korean) sentence two times. The analyses were based on 600 sentences (120 participants * 5 sentences), but sometimes some speaking was added in the analysis if needed. All audio recordings were done using a Marantz PMD 650 with a Shure SM 10A microphone, digitalized at 44.05 kHz and 16-bit resolution.

3.3. Measurements

- Five sentences of each language (English and Korean) were used to evaluate the suprasegmentals of each group. Several acoustic measurements of fundamental frequency (in Hertz) and duration (in milliseconds) were made. Duration and fundamental frequency were measured using a waveform display with a time-locked wideband spectrogram with the software Praat (5.3.04). All acoustic cues were measured from the initial acoustic signal in both the waveform and the spectrogram to the final acoustic cues of the boundary such as burst (Kent and Read, 2003; Ladefoged, 2001). Variables of F0 range, speech rate, and mean F0 and syllable duration in the sentence-final words were calculated. Details of each specific measurement are outlined in the following sections:F0 range: The range was measured from the highest point to the lowest point of the fundamental frequency: overall range of F0 across the sentence. I used the F0 tracing generated by Praat to determine peaks and troughs.Sentence duration: The sentence duration rate is operationalized as timing duration measured from the initial acoustic signal of the sentence in both the waveform and the spectrograms to the final acoustic or spectral cues of the sentence ending.Mean F0 and syllable duration in the boundary: This study measured mean F0 and the syllable duration in the sentence-final word because the final lengthening/ strengthening is a meaningful linguistic mark. In this study, most final words consisted of cross-syllables with lexically stressed and the unstressed vowels have been checked.

- These measures were analyzed with Repeated Measures of Analyses of Variance (RM ANOVAs) which were conducted for statistical evaluation of the groups with the following parameters: Dependent variables of fundamental frequency, sentence duration, F0 and syllable duration at the boundary were examined by both fixed factors of L1 and length of immersion (LISK-E, SISK-E, NE, LISE-K, SISE-K, NK). The repeated measure of phrases was used in order to consider the individual variation (each sentence by each speaker) along with within group variation. Repeated measures were used in order to account for within speaker variance in pronunciation. A repeated-measures design is able to factor out some of the variation that occurs within individuals.

4. Results

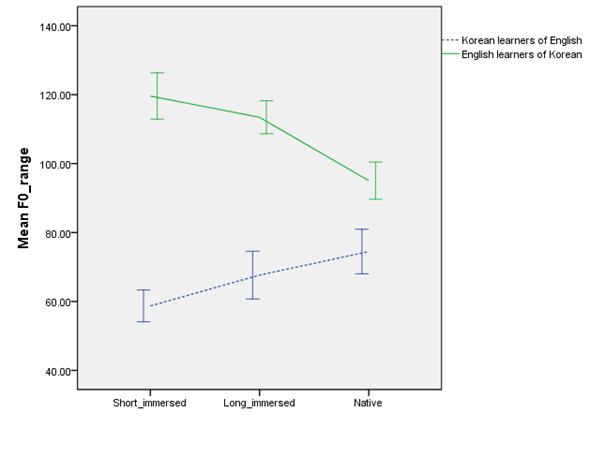

4.1. F0 Range

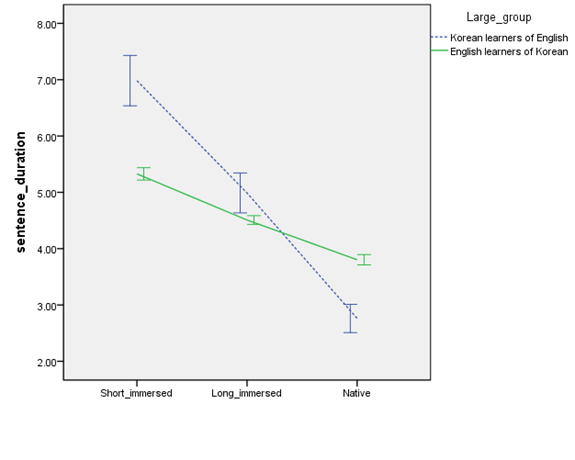

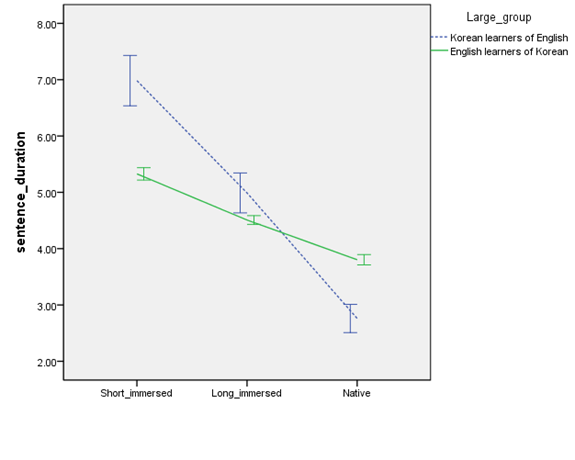

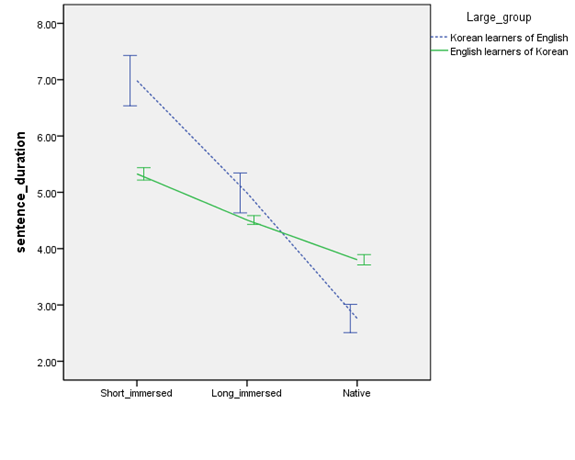

- For L2 English learners, the RM ANOVA confirmed that there was a significant effect on L1, F(2,600) = 149.891, p <.001, not on the length of immersion, p > .05. The interaction of two factors, L1 and the length of immersion, implied significant effect as F(2,600) = 12.049, p <.001. Tukey’s tests (p < .05) revealed that the F0 range of Korean learners of English had been decreased over the length of immersion, while English learners of Korean had increased the range over each immersion level. Figure 1 presents the F0 range produced by the six groups. The results showed that F0 range of Korean learners of English has been decreased step by step (119 Hz, 113 Hz, 95 Hz for Korean learners of English), while English learners of Korean showed the improvement of F0 range (58 Hz, 67 Hz, 74 Hz for English learners of Korean). Either L1 group, the longer immersed groups approach closer to the F0 range of native speakers. This result supports the proposal that F0 range of the advanced learners follows the native speakers’ patterns; more fluent learners of English as a second language have a wider F0 range when speaking English than less fluent learners and also that more fluent Korean learners exert a narrower F0 range[2][5].Recently, the debate has focused on whether a variant F0 range could be evidence of the influence of the native language[12], or reflect a lack of proficiency in the second language[13]. Kang, Guion-Anderson, Rhee, and Ahn (2012) reported that a lower proficiency with English as a second language is related to a narrower F0 range for Koreans, while a lower proficiency with Korean as a second language is tied with a wider range for native English speakers. It is noteworthy that the F0 range of Korean spoken by native Koreans is only 70% of the F0 range of English produced by native English speakers.This study supports the hypothesis that the variation of F0 range reflects both effects; the short-immersed group gets strongly influenced by the L1 effect, while the long-immersed group reflects the degree of proficiency. That is, the F0 range for the longer immersed groups for both L2 English and Korean learners closely approximated the range of the native speakers, perhaps showing less L1 interference than the shorter immersed groups.

| Figure 1. Group means for F0 range (±1 SE) for three levels of two L1s |

| Figure 2. Group means for Sentence duration (±1 SE) for three levels of two L1s. Y-axe represents durational timing in seconds |

4.2. Sentence Duration

- For Korean learners of English, the RM ANOVA confirmed a significant effect of group on L1, F(1,600) = 23.884, p <.001, as well as on the length of immersion, F(1,600) = 438.648, p < .001. The interaction of both variables show the significant effect as F(2, 600) = 113.765, p < .001. Tukey’s tests (p < .05) revealed that the sentence duration was larger for the short-immersed group of Korean learners of English (6.98 syllables per second), the long immersed group (4.50 syllables per second), and native English speakers (2.76 syllables per second) and that it was larger for the short-immersed group of English learners of Korean (5.32 syllables per second), medium for longer-immersed group (4.98 syllables per second), and shorter for native Koreans (3.80 syllables per second). Figure 2 presents the mean value of sentence duration for the related groups. Considering that sentence duration is closely related with speech rate, the results agree with previous work in which more native-like speech was produced with a faster speech rate regardless of language effects[5][6]. In this experiment, the longer-immersed group produced sentences with intermediate sentence duration between the shorter - immersed and native groups, indicating that immersion has a significant influence on sentence duration. The reason why both shorter-immersed groups produced the larger sentence duration is closely tied with universal proficiency of L2. It means that the poor L2 learner inherently meets a fluency problem: failure to control various components of an utterance, including content versus function words, stressed versus unstressed syllables, and focused versus unfocused words[5]. For example, L2 learners tended to produce function words and unstressed syllables with higher pitch and longer duration than the native groups[6]. On the contrary, the longer-immersed L2 groups approached to the native speakers’ speech rate, controlling stress/unstressed syllables, strengthening content words, weakening the functional words, and lengthening the pitch contour on focused words, leading to the fast speech rate.

4.3. Duration and Mean F0 of Phrase-final Syllable

- Boundary cues are realized in prosodic units at the end of the sentences as the form of longer duration and higher pitch[14]. For L2 Korean learners, the RM ANOVA revealed that there was a significant effect of L1 group on the syllable duration in the sentence-final words, F(1,600) = 261.677, p <.001, and also of the length of immersion, F (2,600) = 65.724, p <.001. The interaction of both effects is significant: F(2,600) = 22.468, p <.05. Tukey’s tests (p < .05) revealed that the duration was longer for the shorter immersed groups than both the longer immersed and the native groups. In the phrase-final duration of the syllable which calculated at the boundary words, its boundary duration for Korean learners of English is the longest for native speakers of English (0.90 ms), then the longer immersion group (0.61ms), and the least for the short-immersed group (0.54 ms), while its duration for English learners of Korean shows little difference among three groups: the longest for native Korean group (0.29 ms), then the longer immersed English group (0.27 ms), and the least for the short-immersed English group (0.25 ms). This implies that final lengthening could be the crucial variable in deciding L2 proficiency only for English, not for Korean.

| Figure 3. Group means for syllable duration at the boundary (±1 SE) for three levels of two L1s |

| Figure 4. Group means for mean F0 at the boundary (±1 SE) for three levels of two L1s |

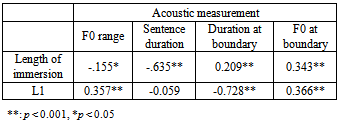

5. Relationship between Suprasegmental Production and Both Effects

- The production analysis reported that both effects, L1 and the length of immersion, influence L2 learners’ prosody acquisition of the target languages significantly. One of the remaining questions on the production tests is to what extent their accuracy improvement for the suprasegmental cues could be associated with both factors. For the analysis, both effects and their values of suprasegmentals examined in this study were submitted to correlation analyses. Zero-order correlations were computed between their suprasegmental measured values (F0 range, sentence duration, and the duration and mean F0 at the boundary) and both effects. The analysis indicates that most of acoustic values measured in this study are differently correlated with both effects (Table 2), suggesting that sentence duration, one of the temporal cues, is strongly correlated with the length of immersion, while syllable duration at the boundary is correlated with the effect of L1. It means that speech rate could improve over the length of immersion and final lengthening is dramatically different by L1 effect.

|

6. Discussion

- Both immersed groups have some shared features as well as some contrastive characteristics at the same time on how L2 prosody is influenced from the view of L1 interference and universal L2 development. L1 interference is strongly appeared in boundary cues. On the contrary, the length of immersion is closely associated with sentence duration and F0 range, in which universal prosody features of L2 acquisition are involved. These cues have been proved to improve along with length of immersion.Some cues, however, are closely tied with L1 language background. In this study, both factors realize differently in bi-direction of Korean to English and English to Korean: wider F0 range and final strengthening at the boundary for longer immersed English learners of Korean versus narrower F0 range and final lengthening for longer immersed Korean learners of English. However, both advanced groups hold common characteristics: faster speech rate. It means that the speech rate is not related with L1 background, but with the length of immersion. Both longer immersed groups produce the fast speech rate, regardless of L1 background. The study implies the result that L1 interference realizes differently at the boundary: mean F0 and syllable duration. The longer immersed English learners of Korean move their pitch height from lower pitch to higher pitch at the boundary. On the contrary, the longer immersed Korean learners of English have lengthened the syllable duration of sentence-final word from shorter to longer syllable duration. It means that the effect of immersion applies the suprasegmental cues differently at the boundary.To date, final lengthening/strengthening in IP (intonational phrase) has been known as characteristics realized cross-linguistically[14][15]. It is certain that final lengthening/strengthening plays the role of mark representing breakdown between two sentences cross - linguistically. This study, however, suggests different implication depending on the target language. Between two sentences (or phrases), the special feature which realized as final lengthening is confined to Korean learners of English, not to English learners of Korean. On the contrary, final strengthening is applied for English learners of Korean, not for Korean learners of English. The issue of immersion in this study supports the hypothesis that intensive exposure to L2 environment accelerates the acquisition of the most important intelligible suprasegmental cues such as speech rate and boundary cues. In this study, a high exposure to opportunities to learn English or Korean under the immersion environment leads to the fast speech rate, lengthening and strengthening in the boundary, and wider/narrower F0 range. Although subjects’ age of first exposure to the L2 has been considered as the critical factor to decide the native-like pronunciation[2], this study supports the hypothesis that immersion is eligible to be a critical variable.In a short summary, the bi-directional study between two language learners implies that suprasegemental features are not acquired equally. That is, L1 interference features such as F0 range and syllable duration at the boundary are mixed with the immersion cues like speech rate. For instance, pitch at the boundary for longer immersed Korean learners of English has been decreased, contrary with higher pitch of native English speakers as a realization of final strengthening. Thus, several years of extensive immersion does not guarantee a native-like production of suprasegmentals. This means that some speech fluency aspects are native-like, while others are not. More specifically, several years of immersion appear to improve fluent prosody as shown in speech rate and overall F0 range. On the other hand, more local boundary cues are found to be less native-like.

7. Conclusions

- Immersion experience was found to have some influence on the production of L2 suprasegmentals in terms of F0 range, sentence duration, and syllable-duration and mean F0 at the boundary. Long-immersed L2 learners exhibited patterns more similar to those of native speakers than the short-immersed L2 learners as a whole, regardless of L1 language background. The long-immersed L2 groups are reported to have more native-like suprasegmentals than a short-immersed group, but the difference could be found at the boundary: final strengthening for Korean learners of English and final lengthening for English learners of Korean. From this result we can infer a facilitative effect of immersion on the production of suprasegmentals in a second language acquisition: L1 interference and L2 immersed effect. It means that L1 interference strongly influences on the boundary cues, while L2 immersion experience have a positive effect on sentence duration (speech rate) and global F0 range.Further research is needed to study why some boundary cues are comparatively hard to acquire and how these characteristics contribute to diminished intelligibility or to the detection of a non-native accent.

Appendix

- (1) English scriptA: What are you doing?B(01): Yep. I am studying Mathematics.A: What! Mathematics. Why don't you study Natural science? You have exam tomorrow.B(02): I already studied it. Anyway, did you have lunch?A: No. I didn’t have lunch yet.B(03): Didn’t you? Come over here. Let’s have lunch together.A: No, I didn’t have time.B(04): Anyway you take care of yourself. A: I am not sure. Do you have time tomorrow?B(05): I don’t know. I will take exams tomorrow. (2) Korean Script (Romanized letters)A: Ner yergiseo muersulhani?B(01): Ung. suhakul kongbuhago isser.A: suhakilago? wae jayeronwhahakul kongbuhaji anni? naeil sihermijana.B(02): imi kongbu haesser. kurendae, ner jeomsim merserkni?A: ani. ajik jeromsim anmerkerser.B(03): Kurae? yergiwa. hamge jermsim merkja.A: ani. nanun sigani erber.B(04): erjasstun momjjaenggera.A: Jalmoruggeer. naeil sigani issni?B(05): Mola. naeil sihermi isser.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML