-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

p-ISSN: 2326-0750 e-ISSN: 2326-0769

2013; 2(2): 17-27

doi:10.5923/j.linguistics.20130202.02

An Overview of Politeness Theories: Current Status, Future Orientations

Mohsen Shahrokhi, Farinaz Shirani Bidabadi

Department of English, Shahreza Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahreza, Isfahan, Iran

Correspondence to: Mohsen Shahrokhi, Department of English, Shahreza Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahreza, Isfahan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper is an endeavour to depict a holistic image of theories of politeness ranging from classic theories of politeness to the most up-to-date theories. To this end, the reviews of the social norm view, the conversational maxim view, the conversational-contract view, Brown and Levinson’s face-saving view, Arndt and Jannaey’s Supportive face-work and interpersonal politeness, Spencer-Oatey’s view of rapport management, Ide’s notion of discernment and volition, Scollon and Scollon’s intercultural communication, and Watt’s politeness view are provided and the main tenets of every theory are explained critically. The explanation of the current status of theories of politeness would be followed by conclusions that provide some orientations for future studies conducted on politeness.

Keywords: Politeness, Face, Face-threat, Verbal Interaction

Cite this paper: Mohsen Shahrokhi, Farinaz Shirani Bidabadi, An Overview of Politeness Theories: Current Status, Future Orientations, American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 17-27. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20130202.02.

Article Outline

1. Origins of Politeness

- As a socialization process competent adult members in every society learn how to behave politely, linguistically and otherwise. Hence, politeness has not been born as an instinctive mankind property, but it is a phenomenon which has been constructed through sociocultural and historical processes.Historically, traces of the English term ‘polite’ can be found in the 15th century. Etymologically, however, it derives from late Medieval Latin politus meaning ‘smoothed and accomplished’. The term 'polite' was synonymous with concepts such as ‘refined’, ‘polished’ when people were concerned. In the seventeen century a polite person was defined as ‘one of refined courteous manners’, according to the oxford dictionary of etymology. [14] believes that in French, Spanish, German, and Dutch courtesy values such as ‘loyalty’ and ‘reciprocal trust’ were used by upper class people in the Middle Ages to distinguish themselves from the rest of people. According to[14] the primary purposes behind following courtesy values were achieving success, winning honors and behaving appropriately at court. In Persian, adab (politeness) is defined as the knowledge by which man can avoid any fault in speech, according to Dehkhoda dictionary (1980). Jorjani, however, extends the realm of politeness to the knowledge of any affair through which man is able to abstain from any kind of fault which would result in a peaceful and brotherly relationship among people.[15] states that during renaissance period not only upper class people but also the rest of people were concerned with the amelioration of social manners and social tact as well as a civilized society. The consideration that a person owes to another one was of great importance to maintain and balance social relation; moreover the reciprocal obligations and duties among people of all walks of life needed to be determined.

2. Politeness: Preliminary Remarks

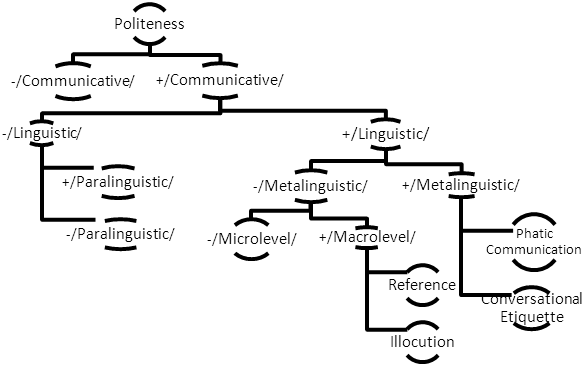

- Developing theories of politeness or investigating norms of politeness in different cultures as well as presenting the definition of politeness have been the focus of attention by most studies on politeness[5, 28, 17, 7, 55, 57].The status que in politeness studies reveals “numerous definitions of politeness”[57] that indicates “varied conceptualizations of politeness”. Several factors have given rise to the current states of affairs among which[57] calls the lack of a clearly differentiation and a thoroughly examination of the relationship between commonsense and scientific notions of politeness as one of the important factors.[55] uses the term “first-order politeness” and “second-order politeness to clarify the commonsense and scientific notions of politeness. They state that: First-order politeness corresponds to the various ways in which polite behavior is perceived and talked about by members of socio-cultural groups. It encompasses ... commonsense notions of politeness. Second-order politeness, on the other hand, is a theoretical construct, a term within a theory of social behavior and language usage[55].First-order politeness covers the common notion of politeness as realized and practiced by members of a community in everyday interactions.[16] divides first-order politeness into three components, namely “expressive, classificatory, and metapragmatic” politeness. Expressive first-order politeness is the polite intention that the speakers manifest through speech. The use of politeness markers such as ‘please’, and such conventional formulaic expressions as ‘thank you’ are instances of expressive first-order politeness. Classificatory first-order politeness involves the classification of behaviors as polite and impolite based on the adreessee’s evaluation. This evaluation derives from metapragmatic first-order politeness, that is, the way people think of politeness and the way it is conceptualized in various interactional contexts. Altogether, first-order politeness is an evaluation of ordinary notion of politeness with regards to the norms of society; the way politeness is realized through language in daily interactions by speakers as well as the hearer’s perception and assessment of politeness. The study of linguistic politeness as one of the aspects of interaction has been considered as first-order politeness by researchers (e.g.[13, 25]) and has been the topic of investigation.At the level of second-order politeness, it is attempted to develop a scientific theory of politeness. The theory can elaborate the functions of politeness in interaction and provide the criteria by which im/polite behavior is distinguished. The second-order politeness also can present universal characteristics of politeness in different communities. Accordingly, various models of politeness have tried to account for politeness universal characteristics as a theoretical construct (e.g.[6]). As[55] call for a clear distinction between commonsense and scientific notions of politeness to prepare the ground to have a better understanding of politeness definitions,[12] also argues that a distinction between commonsense and scientific notions of politeness is necessary. He observes that when researchers talk about politeness they “somehow never seem to be talking about ... those phenomena ordinary speakers would identify as ‘politeness’ or ‘impoliteness’”. Moreover, the presuppositions that these researchers adopt when discussing politeness “do not come from their talk with ordinary speakers asking what these ordinary speakers ... have to say on this matter”[57]. As a result, scholars elevate “a lay first-order concept ... to the status of a second-order concept”[55]. Put another way, they “qualify certain utterances as polite or impolite, where it is not always clear and sometimes doubtful whether ordinary speakers do[so]”[12].With regard to the above remarks, in the following section a thorough introduction of notions of politeness and different conceptualizations of this notion proposed through different theories will be dealt with. However, introductory remarks will be presented below first. As for the manifestation of politeness,[22] puts forward a categorization by which he states that politeness can be expresses through communicative and non-communicative acts. In spite of the fact that there is no “unanimous agreement as to what is interpreted as communicative” as[41] believes, but the categorization might be of help as a starting point to classify various manifestation of politeness.According to figure 1, acts that are only realized instrumentally can be categorized as non-communicative politeness. The case can be observed, for instance, when students stand up as a professor enters the classroom.

| Figure 1. Politeness Manifestation[41] |

3. Politeness: Notions, Conceptualizations, and Theories

- Politeness research ranged from developing theoretical notions of politeness and claiming universal validity across diverse cultures and languages to investigate politeness in individual cultures to discover cultural slant on commonsense notions of politeness. However, relevant literature of the field lacks a consistency of definitions of politeness among researchers. In additions to inconsistency of politeness definitions, there are cases in which the writers even fail to define politeness explicitly due to their blurry comments of the term.[17] critical overview of the way researchers approach politeness, leads him to come up with four major models by which researchers can treat the term politeness more systematically and conduct their research based on the model of their taste. He explains the models and provides a characterization of every model to shed light the major pillars of each one. Although Fraser just classifies the past research literature treatment of politeness, his classification is a point of departure for many researchers of the field since the date of publication onward to base their theoretical framework on a systematic model of politeness; and his work has been one of the most frequent sources referred to in the relevant investigation and explorations of politeness. As a point of departure, therefore,[17] four perspectives namely, the social norm view, the conversational maxim view, the face-saving view, and the conversational-contract view as the most classic perspectives on the treatment of politeness are discussed first. In the subsequent section then, other relevant views and conceptualizations will be elaborated as well.

3.1. The Social Norm View

- According to Fraser “the social norm view of politeness assumes that each society has a particular set of social norms consisting of more or less explicit rules that prescribe a certain behavior, a state of affairs, or a way of thinking in a context”[17]. One example of these rules is the difference between a formal address ‘vous’ and an informal ‘tu’ in French.[24] was one of the first to express this view in her study of politeness phenomena in the Japanese society. According to[44], within the social norm view politeness is “seen as arising from an awareness of one’s social obligations to the other members of the group to which one owes primary allegiance.”According to Held[23] the social norm view consists of two factors:Status conscious behavior which is realized by showing deference and respect to others’ social rank.Moral components and decency which involves a concern for general human dignity (by protecting others from unpleasant intrusion, and respecting taboos and negative topics) as well as the maintenance of others’ personal sphere (by reducing or avoiding territorial encroachment).The social norm view has been corresponded to a type of politeness called “discernment” (wakimaei) by some researchers like[55]. Ide states that wakimae is “the practice of polite behavior according to social conventions”[24]. Wakimae is a behavior according to “one’s sense of place or role in a given situation”.[24] believes that this is helpful in order to have a friction free communication which runs smoothly. Socio-cultural conventions have also been regarded by[26] as one of the frameworks which shape politeness as “social politeness” which is akin to the social norm conventions. “Social politeness” gives prominence to in-group conventions to organize the interaction among members of groups smoothly. Such conventions as “conversational routines”, “politeness formulas”, and “compliment formulas” are among strategies that prepares the ground for members of a group to get “gracefully into, and back out of, recurring social situations such as: initiating ... maintaining ... and terminating conversation”[26].

3.2. The Conversational Maxim View

- The second politeness model, i.e. the conversational maxim view, relies principally on the work of[20]. The cornerstone of politeness studies is based on Cooperative Principle (CP) and according to[16] Grice’s Cooperative Principle is “the foundation of models of politeness”. Among the main contributors to this view[31, 33] and[37] have been the major figures, although[11] and[30] are also among adherents to this view though to a less extent.Grice argues that “conversationalists are rational individuals who are, all the other things being equal, primarily interested in the efficient conveying of message”[17]. The superior principle according to Grice is Cooperative Principle (CP) that is to “make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged”. To put it more simply, Cooperative Principle calls for what one has to say, at the time it has to be said, and in the manner in which it has to be said. In[3] term CP means ‘operating together’ when the creation of a verbal interaction is expected.Grice bases the cooperative principle on four maxims, which he assumes speakers will follow. The maxims are termed, as[32] reports, maxim of quantity (say as much and no more than is necessary), maxim of quality (say what is true), maxim of relevance (say what is relevant), and maxim of manner (say in a non-confusing way). Grice believes that in order for the speakers to produce utterances which are informative, true, relevant, and non-confusing they have to adhere to CP. However, Grice also explains situations in which one or more of the maxims are violated in an attempt for extra meaning. That is to say, the speakers lead the addressee’s attention to making an inference, ‘conversational implicature’ in Grice’s term[3] suggests that conversational implicature happens when an inference is got from what the speakers say; conversational implicature is triggered through the violation of one or more of maxims by the speaker and is elicited by the hearer relying on the assumption that the speaker is still adhering to the CP. People who do not follow the maxims in communication but still seem cooperative, resort to another set of rules to communicate that according to[31] are called “the rules of politeness”.[37] uses the term “the politeness principle” to refer to the same rules.[31] “the rules of politeness and[37] “the politeness principle” can be covered by the umbrella term of conversational maxim view of politeness.Despite frequent adoption of Grice’s CP, however, it has been encountered some critiques.[37] states that Grice’s “framework cannot directly explain why people are often indirect in conveying what they mean” .[29] also questions the universality of Grice’s maxims, because according to Keenan achieving politeness through CP is not observed in all cultures.

3.2.1. Lakoff's Rules of Politeness

- Although Cooperative Principle fails to account for politeness directly, but as a reference it gave rise to the formulation of the other theoretical and empirical work such as Lakoff’s rules of politeness.[31] integrated Grice conversational maxims with her own taxonomy which consisted of two rules: “be clear” and “be polite”. She summarized Grice’s maxims in her first rule and proposed the following sub-rules as the sub-rules of her second rule, i.e. “be polite”. These sub-rules aim at “making one’s addressee think well of one” and accordingly “imparting a favorable feeling” as far as the content of communication is concerned[31]. She put forward the sub-rules of politeness as follows:1) Don’t impose2) Give options3) Make a feel good – be friendlyThe first sub-rule, according to[32], is concerned with “distance and formality”, the second rule is concerned with “hesitancy” and the third one with “equality”. [31] states that speakers employ the above-mentioned rules to either express politeness or avoid offence as a consequence of indicating speaker/addressee status. Rule 1 (Don’t impose) is realized once a sense of distance is created between the speaker and hearer by the speaker. The realization of rule 1 would result, according to[32], in “ensuring that status distinctions are adhered to, that no informality develops, that the relationship remains purely formal.” The use of title+last name as a form of address, the preference of the passive to the active, and the use of technical terms to avoid the unmentionable in such situations as medical, business, legal, and academic ones are examples of the implementation of this rule.As for Rule 2 (Give options) as “the rule of hesitancy” in[32] term, the speaker gives the addressee options to express uncertainty over the speech act he, i.e. the speaker, is performing. Lakoff states that in realizing rule 2 “the speaker knows what he wants, knows he has the right to expect it from the addressee, and the addressee know it”[32]. Rule 2 is also used as a sign of true politeness i.e., “the speaker knows what he wants, but sincerely does not wish to force the addressee into a decision”. The use of “please”; particles like “well”, “er”, and “ah”; euphemisms; hedges like “sorta”, “in a way” and “loosely speaking” can be considered as some of linguistic realizations of rule 2.Rule 3 (make a feel good) is concerned with “the equality rule” which expresses that although the speaker is superior or equal in status to addressee, but the speaker implies that s/he and the addressee are equal to make addressee feel good. This sense of camaraderie or solidarity can be verbally expressed by the use of first names or nicknames which gives the impression of an informal relationship between speaker and addressee; particles such as “I mean”, “like” and “y" know” which enable speaker to show with it his feelings about what he is talking about[32]. The linguistic manifestation of rule 3 can be achieved through giving compliments and using explicit terms for expressing taboo terms.[34] considers modern American culture as a culture in which “the appearance of openness and niceness is to be sought”.Lack of sufficient empirical evidence for cross-cultural politeness strategies has been named as one the criticisms addressing Lakoff’s notion of politeness. She also does not distinguish clearly polite behavior from appropriate behavior. According to[16] “what is considered appropriate during social interaction (e.g., greeting, leave-takings, and other routine formulas) may not always be interpreted as polite behavior”.

3.2.2. Leech's Politeness Principle and Maxims of Interaction

- Relying on a Grician framework,[37] proposed the Politeness Principle (PP) and elaborated on politeness as a regulative factor in communication through a set of maxims. Politeness, as[37] found out, is a facilitating factor that influences the relation between ‘self’, by which Leech means the speaker, and ‘other’ that is the addressee and/or a third party. To Leech politeness is described as “minimizing the expression of impolite beliefs as the beliefs are unpleasant or at a cost to it”[37]. Leech attached his Politeness Principle (PP) to[20] Cooperative Principle (CP) in an attempt to account for the violation of the CP in conversation. The author regarded politeness as the key pragmatic phenomenon not only for the indirect conveying of what people mean in communication but also as one of the reasons why people deviate from CP.[37] explains the relation between his own Politeness Principle and Grice’s Cooperative Principle as follows:The CP enables one participant in a conversation to communicate on the assumption that the other participant is being cooperative. In this, the CP has the function of regulating what we say so that it contributes to some assumed illocutionary or discoursal good(s). It could be argued, however, that the PP has a higher regulative role than this to maintain the social equilibrium and the friendly relations which enables us to assume that our interlocutors are being cooperative in the first place. [37] proposed a pragmatic framework consisting of two components: textual rhetoric and interpersonal rhetoric which are constituted by a set of principles each one respectively. Politeness Principle as a subdivision is embedded within the interpersonal rhetoric domain along with two other subdivisions, that is, Grice’s Cooperative Principle (CP) and Leech’s Irony Principle (IP).[37] as cited in[41] regards the IP as “a secondary principle which allows a speaker to be impolite while seeming to be polite”, in other words, the speaker seems ironic by violating the cooperative principle. “The IP then overtly conflicts with the PP, though it enables the hearer to arrive at the point of utterance by the way of implicature, indirectly”.One very important characteristic in Leech’s theory is the distinction he makes between “absolute politeness” and “relative politeness” with an emphasis on the former, in his attitude. “Absolute politeness” is brought into play in an appropriate degree “to minimize the impoliteness of inherently impolite illocution” and “maximizing the politeness of polite illocution”[37]. “Absolute politeness” involves the association of speech acts with types of politeness and has a positive and negative pole, since some speech acts, such as offers, are intrinsically polite whereas others such as orders are intrinsically impolite. “Relative politeness”, as[37] states is relative to the norms of “a particular culture or language community” and context or speech situation is influential on its variations. This relativity is a matter of the difference of language speakers in the application of the politeness principle.(I) TACT MAXIM (in impositives and commissives)(a) Minimize cost to other (b) Maximize benefit to other](II) GENEROSITY MAXIM (in impositives and commissives)(a) Minimize benefit to self (b) Maximize cost to self](III) APPROBATION MAXIM (in expressives and assertives)(a) Minimize dispraise of other (b) Maximize praise of other](IV) MODESTY MAXIM (in expressives and assertives)(a) Minimize praise of self (b) Maximize dispraise of self](V) AGREEMENT MAXIM (in assertives)(a) Minimize disagreement between self and other (b) Maximize agreement between self to other](VI) SYMPATHY MAXIM (in[expressive])(a) Minimize antipathy between self and other (b) Maximize sympathy between self and other]The degree of tact or generosity appropriate to a particular speech act can also be determined by a set of pragmatic scales proposed by[37]. The scales have been termed the optionality scale (“the amount of the choice of addressee to perform a proposed action”)[38], the indirectness scale (“how much inference is involved in the proposed action”)[48], the authority scale (“which describes the degree of distance between the speakers in terms of power over each other”)[41], and the social distance scale(which describes the degree of solidarity between the participants” ).The Tact Maxim is used for impositives (e.g. ordering, commanding, requesting, advising, recommending, and inviting) and commissives (e.g. promising, vowing, and offering). These illocutionary acts refer to some action to be performed by either the hearer (i.e. impositives) or the speaker (i.e. commissives). Under this maxim, the action “may be evaluated in terms of its cost or benefit to S or H” using a cost-benefit scale[37]. Using this scale, an action which is beneficial to H is more polite than one that is at a cost to H. The Generosity Maxim, which works most of the time together with the Tact Maxim, concerns impositives and commissives too. However, the hypothesis that the Tact Maxim receives greater emphasis than the Generosity Maxim results in impositives that omit reference to the cost to H of an action and that describe the intended goal of the act as beneficial to S. Approbation Maxim requires people to avoid talking about whatever unpleasant, especially when the subject is related to the hearer. The strategies of indirectness included in Politeness Principle, however, let speakers balance the unpleasant side of criticism. Modesty Maxim which works closely with Approbation Maxim involves both self-dispraise and avoidance of other people dispraise due to impolite nature of dispraising others. Observing the Modesty Maxim is a matter of relativity, that is to say, it is effective when one avoids being tedious and insincere as a result of continuous “self-denigration” in any situation[37]. The Approbation Maxims along with the Modesty Maxim are concerned with expressives and assertives.The next two maxims of politeness, namely the Agreement Maxim and Sympathy Maxim, concern assertives and expressives respectively. The Agreement Maxim seeks opportunities in which the speaker can maximize “agreement with other” people from one hand, and can “mitigate disagreement by expressing regret, partial disagreement, etc.” from the other hand[37]. Concerning the Sympathy Maxim, it is best instantiated in condolences and congratulation speech acts when speakers make an attempt to minimize antipathy with others and maximize sympathy with others.[37] believes that all his maxims are not of the same importance. He points out that the Tact Maxim and the Approbation Maxim are more crucial compared to the Generosity and Modesty Maxims, since in his idea the concept of politeness is more oriented towards the addressee (other) than self. As[37] considers two sub-maxims for every one of maxims, he regards sub-maxim (a) within each maxim to be more important than sub-maxim (b). As such,[37] claims that “negative politeness (avoidance of discord) is a more weighty consideration that positive politeness (seeking concord)”.Leech’s politeness principle has been welcome by both criticisms and praise.[27] as one of the critics believes that Leech’s theory is problematic as far as the methodology is concerned, since a new maxim can be introduced to account for the regulatory of any language use. Hence the number of maxims is infinite and arbitrary. This view has been shared by several researchers as[10, 50, 6, 35, 17, 51, 38, 13, and 53].A second criticism of Politeness Principle theory concerns Leech’s equation of indirectness with politeness. This idea has found many counterpoint cases where a direct utterance can be the appropriate form of politeness in a speech situation[38].Leech’s theory also seems “too theoretical to be applied to real languages”, as[38] states, but “the maxims can be used to explain a wide range of motivations for polite manifestation”.[45] points out that Leech’s maxims do not contribute to the universality of politeness, but they can be used to account for many culture-specific realization of politeness. Leech’s Politeness Principle can also be employed to account for the cross-cultural variability of the use of politeness strategies, as[50] pointed out.[6] expresses that cross-cultural variability will then “lie in the relative importance given to one of these maxims contrary to another.”[37] suggests that in Japanese society, for instance, the Modesty Maxim is preferred to the Agreement Maxim since Japanese mores make it impossible to agree with praise by others of oneself. However, this model is not yet supported by sufficient empirical research cross-culturally and needs to be tested in various cultures for further corroboration.

3.3. The Conversational-Contract View

- In this approach, when entering into a conversation, each party “brings an understanding of some initial set of rights and obligations that will determine, at least for preliminary stages, what the participants can expect from the others”[17]. These rights are based on parties’ social relationships and during the process of interaction there is always the possibility for parties to renegotiate the initial rights and obligations on which the parties have agreed. The rights and obligations define the interlocutors’ duty as a Conversational Contract (CC). Politeness here means operating within the terms and conditions of the existing Conversational-Contract and as long as the interlocutors respect the terms and rights agreed upon at the primary stages, they are interacting politely. Due to the possibility of negotiation and readjustment of terms and rights, there is always the opportunity of negotiating the intentions and behaving politely for the interlocutors. Accordingly,[17] regards politeness as “getting on with the task at hand in light of the terms and conditions of the CC”. Conversational-Contract view is similar to Social Norm view in that politeness involves conforming to socially agreed codes of good behavior. It is different from Social Norm view because in Conversational-Contract view the rights and obligations are negotiable. Universal applicability is a remarkable feature of this model. Socio-cultural norms and patterns are the determinant factors in applying conversational-contract model of politeness.[28] believes that conversational-contract cannot be manifested regardless of members of “specific speech communities”. However, conversational-contract model as[50] reports is not empirically applicable due to the lack of model details.[53] questions the terms and rights as it is not clear what social conditions may prepare the ground for the readjustment and renegotiations of rights and terms. He also believes that the nature of the terms and rights are open to question. Furthermore,[16] calls for further empirical application of Fraser’s model of politeness in cross-cultural context in order to determine the validity of CC.

3.4. Brown and Levinson's Face-Saving View

- The most influential politeness model to date is the face-saving view proposed by[6, 55, 28]. This model is based on constructing a Model Person (MP) who is a fluent speaker of a natural language and equipped with two special characteristics, namely ‘rationality’ and ‘face’. Rationality enables the MP to engage in means-ends analysis. By reasoning from ends to the means the MP satisfies his/her ends. Face, as the other endowment of the MP, is defined as the public self-image that the MP wants to gain.[6] claims that face has two aspects:● Positive face’ which is the positive consistent self-image or ‘personality’ claimed by interactants (in other words, the desire to be approved of in certain respects).● ‘Negative face’ which is the ‘basic claim to territorial personal preserves and rights to non-distraction’ (in other words, the desire to be unimpeded by others).Drawing upon the “rational capacities” the MP is able to decide on the linguistic behavior necessary for the maintenance of face. In short, the emphasis on addressing social members’ face needs results in politeness strategies; polite behavior is basic to the maintenance of face wants. Face wants consists of “the wants of approval” (i.e. positive face) “the wants of self-determination” (i.e. negative face)[28]. Brown and Levinson’s model received many criticisms among which the individualistic nature of social interaction is the most important one.[56] describes the rational model person presented by Brown and Levinson as a model “who is, during the initial phase of generating an utterance at least, unconstrained by social considerations and thus free to choose egocentric, asocial, and assertive interaction”. However, in non-western cultures, where group norms and values is the framework in which the interaction forms, the model speaker proposed by Brown and Levinson is not considered polite.[36] for instance, reports Japanese culture as collective, where the interaction context is influenced by rules representing social group attributes. This also holds true for Chinese culture in which one’s face is highly affected by the group reputation to which one belongs[40].Another criticism addressing Brown and Levinson’s theory, concerns the politeness strategies proposed by the authors. Since no utterance can be inherently interpreted as polite or impolite, consequently any assessment of polite or impolite verbal interaction must be performed with regard to “the context of social practice” as suggested by[53]. As such,[16] find the term “pragmatic strategies” more appropriate than Brown and Levinson’s label “politeness strategies” for describing “the expressions used during the negotiation of face in social interaction”.As for social variables namely, social distance, social power, and ranking of imposition,[6] have also been criticized. They consider the social variables as constant. However,[17] believes the social variables presented by[6] can be changed in a short time span. Therefore, such variables as power and social distance must be treated as constantly changing variables according to the context of the interaction.

3.5. Arndt and Janney’s Supportive Face-work and Interpersonal Politeness

- From the point of psychological research,[1, 2] consider politeness as emotive communication and interpersonal politeness. Emotive communication as reported by[16] “refers to transitory attitudes, feelings and other affective states”. According to[1] emotive communication is realized through verbal, vocal, and kinesic abilities. According to the authors confidence cues, positive-negative affect cues, and intensity cues make up the emotive aspect of interaction. [16] rewrites confidence cue as “the degree of (in)directness or certainty to which an interlocutor approaches or avoids a topic in the presence of another interlocutor, and confidence may be expressed or reinforced verbally, vocally, or kinesically. The next cue, namely positive or negative affect cue is defined as “the verbal, vocal, kinesic activities employed to support interpersonal communication by means of supporting (positive support) or contradicting (negative support) the interlocutor’s point of view” . These cues all together function as maintaining and balancing the course of communication. Drawing on Goffman’s notion of face and Brown and Levinson’ positive and negative face,[1] believe ‘personal autonomy’ and ‘interpersonal support’ are manifested through negative face and positive face respectively. Accordingly, they propose four supportive strategies in their model in order for the interlocutors to negotiate face-work. The strategies, namely supportive positive messages, non-supportive positive messages, supportive negative messages, and non-supportive negative messages can be realized both verbally and non-verbally.[16] concludes that for[1] “politeness is viewed as interpersonal supportiveness and consists of supportive face-work strategies that express positive or negative feelings without threatening the interlocutors emotionally.” The lack of politeness research in cross-cultural context for supporting the validity of this model is the criticism encountering this theory of politeness.

3.6. Spencer-Oatey’s View of Rapport Management

- Based on previous models of politeness, for instance those of[19],[6],[37] and inspiring from Conversational Contract view developed by[17],[46] proposed her rapport management as a framework for politeness studies. Rapport management, as reported by[16] is “the management of harmony-disharmony during social interaction”. Rapport management is realized through two alternatives, namely face management and sociality right management[49]. Face management consists of two dimensions, namely quality and identity.[16] rewrites quality of face as “the desire for people to evaluate us positively (i.e., Brown and Levinson’s positive face) according to our qualities (i.e., competence, appearance)”. Identity of face is “the desire for people to acknowledge our social identities and roles as, for example, a group leader or close friend”. The sociality rights suggested by[49] are made up of equity rights and association rights. The equity rights reflect the idea that everybody deserves fair behavior and it is realized when the cost and benefits between the interlocutors is balanced. The second component of sociality rights, namely association rights is one’s right to have a harmonious relationship with others both internationally and affectively. [16] summarizes Spencer-Oatey’s theory as “an alternative for analyzing sociocultural behavior in social interaction”. Rapport management view “excludes Brown and Levinson’s original notion of negative face in which the individual is seen as an independent member of society; instead, group identity captures the notion of an individual who desires to be perceived as a member of the group”. The model, however, awaits sufficient applications cross-culturally.

3.7. Ide’s Notions of Discernment and Volition

- Inspiring from non-western societies such as Japan and China where the formality in language used in social interaction would provide appropriate levels of politeness, [24] proposed discernment and volition as two notions constituting linguistic politeness.[184] report “the volitional type is governed by one’s intention and realized by verbal strategies, and the discernment type is operated by one’s discernment (or the socially prescribed norm) and is expressed by linguistic form”. The use of linguistic form in which the interlocutors’ differences in terms of rank or role are clearly expressed is the way discernment can be realized. As such, formal forms such as honorifics are different from verbal strategies to[24] and she does not consider honorifics among negative politeness strategies as proposed by[6].Verbal strategies are the medium for the expression of volitional politeness according to[24]. Volitional politeness aims at saving face, as the purpose of[6] theory is to save face.Altogether volition and discernment help the interaction flow smoothly as discernment indicates the speakers contribution to the interaction as far as socially prescribed forms are concerned and volition indicates the speaker’s intention as how polite s/he wants to be in a given situation.[16] points out that “if honorifics or pronouns of address are used appropriately in a particular situation, that is, according to the social norms of a given culture, a person may be perceived as being impolite”.The applicability of Ide’s model in non-Asian languages is still waiting for further research to provide supporting evidence for the validity of this model.

3.8. Scollon and Scollon’s Intercultural Communication

- In their book Intercultural Communication,[47] accounts for face in intercultural context. The terms positive and negative applied by[5, 6] to explain two aspects of face in their theory of politeness is replaced in[47] by the terms involvement and independence in an attempt to avoid any misunderstanding of the terms positive and negative as good and bad respectively. To[47] the term involvement refers to group needs and emphasizes the interlocutors’ “right and need to be considered a normal, contributing, or supporting member of society”. Such strategies as attending to others’ interests and wants, using in-group identity marker, asserting reciprocity and closeness to other members of the society are instances through which involvement can be realized.The other term, independence, highlights the individual nature of interlocutors. Formality, indirectness, and providing the interlocutors with options, all are instances of independence realization. Face system proposed by[47] consists of three components namely Deference face, Solidarity face, and Hierarchy face primarily based on both the difference and the distance between participants[8]. The deference face system is an “egalitarian system in which the participants maintain a deferential distance from each other”. In this system, consequently, the interlocutors had better use independence strategies to minimize the possibility of threatening face or losing face. The solidarity face is “also an egalitarian system in which the participants feel or express closeness to each other”[8] and consider one another equal in social position; the interlocutors, consequently, use involvement strategy to provide a sense of friendliness and closeness. On the contrary, the last component, hierarchy face, is “a system with asymmetrical relationship, i.e., the participants recognize and respect the social differences that place one in a supperordinate position and the other one in a subordinate position”. The dominant interlocutor may use involvement strategy in hierarchy face system; however, the dominated interlocutor employs independence strategies to avoid any face threat addressed to the other interlocutor in the superordinate position.[16] believes that the model proposed by[47] “offers an alternative for examining cross-cultural communication taking into account the face needs of each group”. He adds “Scollon and Scollon’s face systems are instrumental for analyzing the negotiation of face in symmetric (-P) and asymmetric (+P) systems”. Although the model lacks sufficient empirical research, however, it best suits studies adopting a cross-cultural approach.

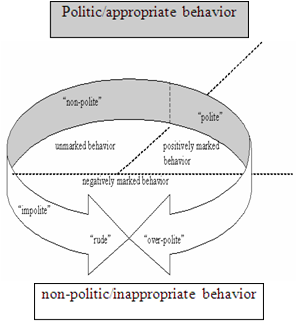

3.9. Watts’s Politeness View

- Adopting a dynamic approach[53] in his book Politeness, makes an attempt to distinguish the common sense or lay notion of politeness from the theoretical notion as emphasized in[13]. As explained in the preliminary remarks section, the former is referred to as first-order politeness or politeness 1 and the latter notion is termed as second-order politeness or politeness 2. As[52] reports “politeness 2 is a socio-psychological notion that is used for the various ways in which members of socio-cultural group talk about polite language usage, whereas politeness 2 is a theoretical, linguistic notion in a sociolinguistic theory of politeness”.[53] introduces politic behavior as appropriate behavior verbal or non-verbal in any social interaction and adds polite behavior as the surplus of politic behavior.[53] believes that the evaluation of verbal and non-verbal behavior as inherently polite or impolite is inaccurate and this evaluation must be subject to the interlocutors’ interpretation of a given contextThe notion of face is treated by[53] as “a socially attributed aspect of self that is temporarily on loan for the duration of interaction in accordance with the line or lines that the individual has adopted”.[53] treats face-work from a new perspective, namely relational work. To him relational work “encompasses various aspects of social interaction such as (in) direct, (im) polite, or (in) appropriate behavior”[16]. According to figure 2, both politic and non-politic behaviors are included in relational work. There are no discrete divisions as unmarked politic behavior and positively marked behavior although they are separated by dotted line; they are of the same nature and there is the possibility of overlapping in particular context as well.

| Figure 2. Rlational work[54] |

4. Conclusions

- This study made an attempt to introduce the principles of the most well-known theories of politeness critically. As it was indicated the earliest theories of politeness (e.g., face-saving theory of[5]) were seeking universal principles of verbal interaction based on which they can provide a universal framework for polite verbal behavior on the one hand. On the other hand, the theories (e.g., face-saving theory of[6];[47]) accounted for the variation of such social factors as distance, power, and weight of imposition respectively and the consequent influence of these variables on the formulation of politeness strategies. Moreover, it was pinpointed that depending on social and contextual variables the interpretation of polite and impolite behavior is different from culture to culture. In this regard, it seems that with the ever-increasing number of interactions among people coming from different cultural backgrounds, two different frameworks should be developed in future orientations of theories of politeness. First, there should be some universal principles and rules considered to be polite for taking into consideration, when people from different cultural background are going to interact politely. This framework could be an intercultural framework of politeness. Second, within every culture, the interaction of people belonging to the same cultural background should follow the rules and principles of the shared norms of interaction within that particular culture, that is, intera-cultural framework. The consideration of culture-specific norms of interaction can contribute to intra-cultural interactions to be polite.Although, the development of a universal framework of politeness for intercultural interactions seems demanding and depends on a number of cultural characteristic, the framework seems plausible, as there are frameworks such as political conventions which are taken into account in international relations. Therefore, the consideration of polite interaction among people coming from different cultural background calls for a universal intercultural framework shared globally.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML