-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Linguistics

2012; 1(3): 47-62

doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20120103.05

The Formation of a School Text Genre Using Collaborative Writing

Wagner Rodrigues Silva

Language Course, Federal University of Tocantins, Araguaína, 77 808620, Brazil

Correspondence to: Wagner Rodrigues Silva , Language Course, Federal University of Tocantins, Araguaína, 77 808620, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In this paper I analyze some examples of collaborative writing in Portuguese,as a mother tongue,resulting in the production of a school newspaper characterized by me as ahybrid text genre. In other words, I investigate the mixing of genres in school andnon-school environmentsresulting from the process of writingin the classroom setting. The name ‘hybrid text genre’ is justified by the fact it appearssemioticallysimilar to other textgenres that are familiar to the individuals who took part in the process described here. These genres are formed in part by literacy events that take place in students’ everyday life in different social contexts. In terms of educational planning, the analysis of data shows that one can hardly predict when a text genre willshow similarities to others and that this is triggeredby the actions of the inumerousindividuals in the complex classroom environment, resulting in new usage and reflection about writing. This experience can trigger innovation in the teaching of a mother tongue.

Keywords: Literacy, Mother Tongue, Learning Gap

Cite this paper: Wagner Rodrigues Silva , "The Formation of a School Text Genre Using Collaborative Writing", American Journal of Linguistics, Vol. 1 No. 3, 2012, pp. 47-62. doi: 10.5923/j.linguistics.20120103.05.

Article Outline

- “Let’s face the truth: this is not a chronicle at all. I mean not only a chronicle.It is not characterized by any genre. Genres do not interest me anymore.I’m interested in mystery. Do I need a ritual for mystery? I think so.To understand how things work. However, I am somehow attached to the ground: I am nature’s daughter: I want to touch, feel,be. And all as part of awhole thing, a mystery. I am only one person. Previously there was a difference between me and my writing (or was there? I don’t know). Now there isn’t anymore. I am a being. And you can be too. Does this scare you? I believe so. But it is worth it. Even if it hurts.It only hurts at the beginning” [1. p. 157].

1. Introduction

- For Clarice Lispector, the mystery involving writing supersedes the potential interest in classifying a text shared with readers. Themeaning of the word mystery, when used to characterize the act of writing, highlights how important writing is and differs fromthe definitions found in dictionaries. Mystery in this case is like a secret, unshareable and unattainable. Writing is described by Clarice as a capturing and involving process that develops during the events experienced by both writers and readers. The mystery in writing is the capturing of moments and things in life aswell as becoming materially involved, implicating the use of bodies and tools. Even though Clarice does not allow herself to become a prisoner of pre-established forms and patterns, her texts are qualified as a certain genre. Actually, the editor of her collection insists on calling them chronicles (editor’s note)[1. p. 5]. I have no doubt that Clarice is aware of how her texts would probably be qualified.I however think that her major interest consisted of experiencing the need to write, which did not end at a full stop. To the contrary, this need was reinforced as her texts were read by her readers. The choice of the epigraph of this study and the fact that Clarice’s text was published in a book of chronicles give life to the ritual characteristic ofwriting. Without extending my arguments, this study has been slightly updated considering that the environment in which it is now being received is different from that of the original publication in a daily newspaper.As a researcher in the field of Applied Linguistics, I am particularly interested in the contribution that text genre can make whilst used by students who are learning how to read and write in Portuguese as their mother tongue. These students were considered behind in terms of learning by their teachers. The action research, based on a different approach of mother tongue teaching through pedagogical work with text genres was used to undermine existing stigmas about the students.In this study, this interest is translatedinto the ritual involved in producing a school paper from text genre references found in non-school environments. Such references enablea type of writing strongly affected by multimodality as the collaborative writing of a school paper analyzed here takes place verbally and visually.Focusing on the way a teacher participated or mediated during the production of a school paper, I studied its structure by analyzing the text, semantics and pragmatics of discourse of the characteristics of genres familiar to the students who made the school paper. These characteristics shape the school paperas a hybrid genre with its own features, which I intend to demonstrate in this study.Hybridism refers to a network built through the interconnection of points that link the usage of writing inside and outside the school1. In the school setting, the points are the distinct text genres used in exercises involving reading, writing and linguistic analysis. Outside the school, the points are genres used by people participating in daily activities involving writing. The connection between the aforementioned environments is established whendaily activities are used as a teaching tool in writing exercises as scaffolds or models in the production of a school paper.The main theories used in my research are arranged here to be utilized as methodologies in studies about literacy[10; 11; 12] as well assystemic functional linguistics on text genres [13; 14; 15; 16]. The studies from the first group of theoriessubstantiate the analysis about the functionality of writing in school and non-school environments and the roles played by their writers. Thestudies from the second group of theories provide the types of analysis to demonstrate the linguistic features found in different writings on textual, semantic and discourse-pragmatic levels, covering the multimodal aspect of theanalyzed genre.

2. Data and Research Methodology

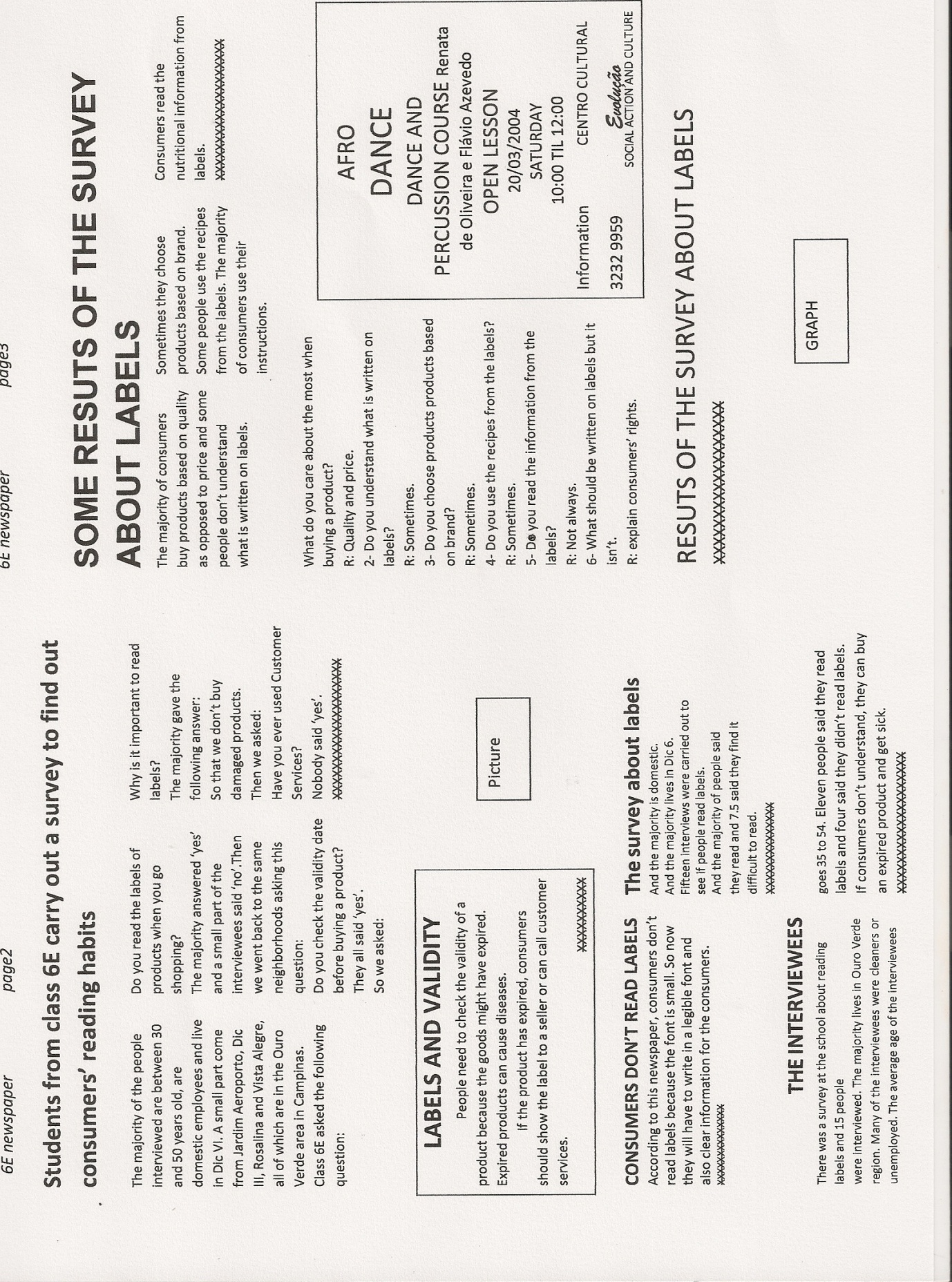

- The research data, which I will use in the attempt to demonstrate the connections that form the networkpreviously mentioned in this study, were created using a methodology based on actionresearch[3], developed during a periodof five months, in a public school in Brazil2. During this period of action research, the teacher who was contributing to this and I jointly prepared a themed teaching unit with instructional exercises including reading, writing and linguistic analysis. These exercises were suggested as a scaffold or model to the production of the school paper analyzed in this study. The paper is the last part of the unit which hadlabels found on products as its subject. In addition toingredients, instructions, tables describing nutritional information and barcodes, which are types of genres found on labels, reportages, questionnaires and graphics were various linkingpoints built into the lessons.The themed unit with instructional exercises worked as a catalyzing genre during the aforementioned application as it allowed the use of a number of text genres during the production of the school paper, contributing to students’ learning process. According to[7. p. 8], “catalyzing genres help to trigger and add potential to actions and attitudes considered more productive in the creation process.Signorini also believes that catalyzing genres become spaces controlled with linguistic and discursivestructures, made of paths and frameworks that are indispensable in the creation of something new”.The teacher taking part in this study has a degree in Modern Languages and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism. At the time the exercise took place, she was working as a teacher and had a contract for an indefinite period of time.She wouldalso undergo a continuous training course, offered by the state government.I was a professor in the groupattended by the teacher who supported me in this research in the aforementioned course. It was then that we both expressed interest in carrying out the research. During the exercise, the theoretical and methodological guidelines of the course regarding the teaching of Portuguese as a mother tongue, based on the concepts of genre and text, were applied. As I supported the teacher to implement activities during the lessons taught during the exercise, as well as elaborate the themed unit with instructional exercises, I think that some allusions made to her work must also be made to mine in the analysis of the research data presented here. In fact, at times our work cannot be detached.Our research was carried out in a 6th grade group of 22 students that due to their learning gap, were made part of Project ABC created by the state government to reduce this gap. According to the teachers who taught these students during the year prior to the exercise, they were truly limited when asked to execute school activities carried out by other students from the same institution, for example, the identification of grammar categories and production of traditional narrative texts, which were commonly required during the lessons. Thespelling and grammar inadequacies found in the writing of the students, as I will present ahead, were also mentioned to justify their referral to the aforementioned project. In some cases, family problems were used as justification by the teachers for the aforesaid limitations, which resulted in the preconceptions that I perceived during my time at the school.These types of exercises as well as social stigmas are some of the technological apparatus, term suggested by[8. p. 164 and 181], responsible for producing learning gaps. These“cultural aspects work as a means of codifying, stabilizing and invoking”us even ifneither“an essential driver of actions nor a passive product or a puppet manipulated by cultural forces; the ability to take action develops frompracticing it, bound by a series of restrictions and powerful relationships. They can be reasonably challenging and explicit, punitive or seductive, reasonably disciplinary or passionate”.Whilst a facilitating genre, the themed unit containing instructional exercises enables students to be less affected by absence or lack of knowledge, abilities or competences as it mobilizes new technological apparatus to work as mediating elements3 in the learning process as well as students’ development.I will investigate some interactions from the lessons recorded during the action research process, as well as some of the records made by students in their notebooks. This, in addition to the school paper itself with its sub-genres, such as news, assembling instructions, graphs, photographs and advertisements, will demonstrate the connection between the different types of writing that constitute the text representing the genre analyzed here. The different versions of sub-genres created from notes written by the teacher, suggesting changes to the students’ writing, as well as the notes themselves, are investigated here. My interest in the notes is justified by the fact the students are requested to rewrite their original textsstrengthening links to writing from different social backgrounds.

3. The School Paperas a Multimodal Genre

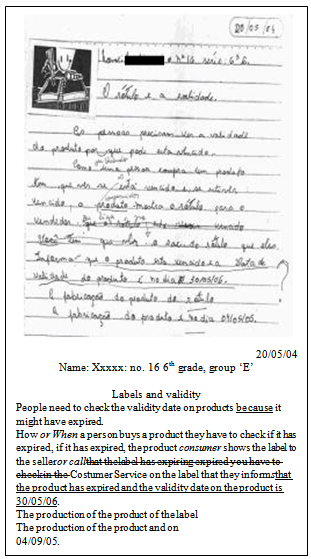

- Considering the progress in literacy research in applied language studies, I think it is not original to say that activities involving writing are not restricted to schools. In fact they embrace various social environments. It is not original either to say that, usually, literacy in the school environment can be rather different from literacy in other social domains[17]. Knowing how writing in schools can contribute to students’ literacy in non-school environments is still a challenge to applied studies. This work attempts to contribute to these studies by investigating the production of a school paper through collaborative writing whilst rebuilding events of the mediation work carried out by the teacher.People read or write to carry out rather precise activities when interacting in writing on a daily basis. These activities are rarely restricted to the evaluation of writing and reading abilities as in the case of school-based literacy practices. With regards to writing at schools, mother tongue teaching traditionally works with a reduced number of text genres, which usually stay in the schools. This could be verifiedin the lessons prior to the exercise that generated the research data analyzed in this study[18; 19; 20; 21; 22]. In non-school environments, literacy practices4take place through a great diversity of text genres, and each genre is used for very specific purposes[12].To illustrate a literacy practice of the school focused here, I will reproduce a draft below written by a female student and corrected by the pedagogical coordinator. The draft5 and its transcription6 are as follows:

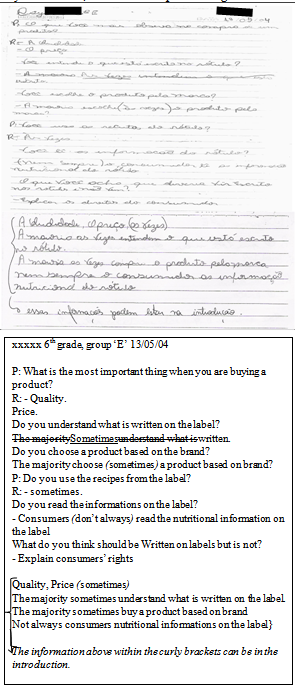

| Example 1. Draft |

4. Situations of Collaborative Writing

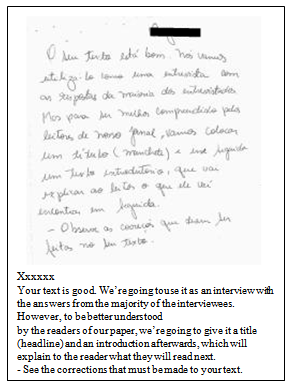

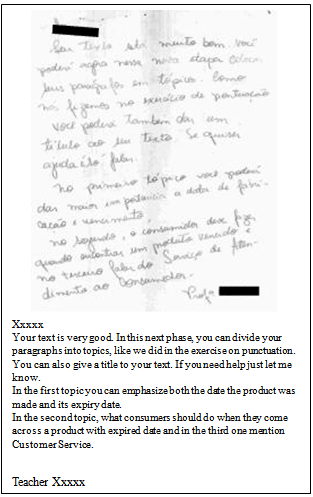

- The final product of a themed unit involving instructional exercises, the school paper studied here is made up of three different text genres, according to the literacy practices that are distinctive to the social backgrounds accessible to the people taking part in the collaborative writing. A preliminary analysis mentioned institutional bulletins, newsletters and daily newspapers as genres that inspired the school paper. With respect to the production of sub-genres, the models used by the participants were other types of writing, typical of school and non-school environments. An interaction between teacher and students is shown below after they read the news story “Brazilians do not understand the information contained in food packaging”, reproduced by me, from JornalNacional’s9 electronic page to be a model for the students’ 10 text. It shows the written version that was going to be read during the news broadcast. The fragment below shows the interaction at the end of a reading11 lesson:/.../586- D: This material was produced based on a survey, which we carried out previously. You are going to write a text similar to this, OK?587- JR: Yes, madam. Can we glue it?588- D: You can glue it on your notebook, and it is your homework, bring it on Friday … let’s tidy up the classroom …/…/In statement 586 the teacher asks the students to write the news texts. As opposed to the planned strategy, which was supposed to study the aspects that characterizes genre in the news, the teacher restricted her work to clarify the parts of the text that the students did not understand. The only aspect addressed here is the thematic content, from which the teacher relates the news to the text to be produced as the news shows the results of a survey about consumers reading labels. In the selected piece of news some results of the study even answer questions from the questionnaire used by the students to generate information to be divulged in their paper, as highlighted by the teacher in another moment during the reading lesson.The teacher’s instructions result in texts written by students, which for scientific purposes, are difficult to be classified in terms of genre. Considering the spelling and grammar inadequacies found in these texts they can easily be used to practice ‘correction’, a type of exercise typical when teaching mother tongue, like the one carried out by the pedagogical coordinator in the draft reproduced in Example 1. In Example 2, I reproduced a sample of a text that is difficult to be classified and rewritten to adapt it for the school paper. Find below the text with interventions carried out by the teacher, and its transcription alongside:

| Example 2. |

| Example 3. |

| Example 4. |

| Example 5. |

| Example 6. |

| Example 7. |

5. Conclusions

- Just like the text written by Clarice Lispector, presented in the epigraph of this article, the text the students cooperatively wrote with the teacher’s support, was not free from being classified as a particular genre in this study. In the same way Clarice said she experienced writing, the students were not prisoners of the school paper either, to the contrary, they wrote a hybrid genre with characteristics placed according to the type of text and mediating tools (technological apparatus) applied during the production. By using the student’s initial text and oral and written mediation, it was possible to conclude the production of the school paper, even though the aim of the teacher’s notes was not initially achieved.As a researcher, the notion of text genre allowed me to visualize the concept of writing as a creative process formed by culturally standardized forms. Some are already known by the students and others are introduced by teachers during the production process in the classroom. In this respect, the terminology ‘school paper’ entails a hybrid genre, formed by different uses of both verbal and visual language specific of non-school and school environments familiar to their authors. By applying multimodal language, students’ knowledge could be communicated, which contributed to their characterization as students learning to read and write.In the established ritual of writing at schools, writing can also be a process that triggers brokerage by the participants of new, culturally standardized forms of writing, which will influence other processes later established and possibly in non-school environments. As I am in favor of work guided by the concept of writing as an uninterrupted production process, even considering modifications that the reader may wish to carry out to my work, I should highlight that the text genres identified here are the consequence of my interpretation of the many activities studied, enabling readers, who are aware of this work to distinguish new connections themselves.This research contributed to show that students were not responsible for school failure. The failure was justified by the traditional approach to the teaching of the Portuguese language, common in a number of Brazilian schools. Such approach is based on a prescriptive perspective of language teaching, which is still based on standard grammar, and it ignores school work using authentic texts that are part of daily life. Such failure is also attributed to the stigmas surrounding the students, who were thought to be incapable of learning the content set in the curriculum, which the teachers attributed to the students’ life stories, characterized by social exclusion.The use of the action research was essential in developing this scientifical investigation, which was enriched by the combining of different research data created during the intervention carried out in the primary and junior high school. Perhaps characterizing this research as a case study might imply the investigation was in some way limited as it does not allow the results to be generalized, which is expected from scientific work created within the positivist paradigm of research. However, I must highlight that this investigation counteracts this paradigm, therefore the relevance of the presented research is especially attributed to the contribution given to the participants and collaborators that are part of the school community focused on in this study. The results produced could also be used as a reference to other training contexts assessed by the reader to be similar to that analyzed here.Finally, by highlighting some characteristics of the students that were once hidden, I finish this study with a favorable comment from the teacher who participated in it. The comment, made during a planning session, was about the performance of the students in becoming readers and writers throughout the exercise: (...) ‘Look, I feel that they felt as if they knew everything, even more so when someone questions something, they are EXPERTS in labels, I see it like this, this is something nobody can take away from them, this knowledge cannot be taken away from them by anybody’ (…)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am thankful to Professor and Doctor InêsSignorini for her preliminarily reading of this work. Having said that, all mistakes or omissions, which might still be present in this text, are my entire responsibility.Thisarticlewasfirstpublished in theperiodical Documentação de Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada (DELTA), in Volume 24, number1, year2008, publishedby Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP), Brazil. I thank Leila Barbara, the periodical editor, for the conceded authorization for publishing this article in English Language.This article was translated to English by Maria Elaine Mendes and RosemeireParada Granada Milhomens da Costa.

Appendix

- Text 1Brazilians do not understand the information contained in food packaging25/11/2003A survey published today concludes that the majority of consumers find it difficult to understand the information found on food packaging labels. Amongst other products, such information is now obligatory on fruit and vegetable packaging as well. An inspector warns a truck driver: the grapes he is transporting did not have any identification saying where they come from. Neither did they have a date on the packaging as required by Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency.The supply center does not have the power to retain the cargo. However the businessman that bought the fruit will be informed of the irregularity and all the food shall have labels by March of thenext year.‘The label is saying to the consumer: look consumer, this product left such and such farm, from such an area, and this is its origin. Therefore you can safely eat it’, explains EuclidesAmorim, the advisor for Ceagesp (Companhia de Entrepostos e ArmazénsGerais de São Paulo–São Paulo General Warehousing and Centers Company).Natural food is the last type to become part of the label era, which still has problems, but there has never been so much information on the package of everything that is being sold. Consumers are still coming to terms with the importance of labels.‘I have problems with high cholesterol, so I have to know what ingredients I am eating’, says an elderly lady.In a survey carried out in São Paulo by the Brazilian Educational Institute for Food Consumption, 61% of the people interviewed said that they read labels. However only 29% compare and decide what they are going to buy based on what is on the label.‘I would say that there is an issue which is not about lack of information, but because there is a gap between the information that is on the label and what the consumers understand from it’, explains PatríciaFukuma, from the Brazilian Institute for Education and Food. It is always possible to improve the text, the writing. What consumers do not want is to stay in the dark, without information on labels.(http://jornalnacional.globo.com/site.jsp)

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML