Jonas N. Akpanglo-Nartey 1, Rebecca A. Akpanglo-Nartey 2

1Office of the Vice-President (Academic), Regent University College of Science & Technology, Accra, Ghana

2Department of Applied Linguistics, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

Correspondence to: Jonas N. Akpanglo-Nartey , Office of the Vice-President (Academic), Regent University College of Science & Technology, Accra, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The phenomenon of language endangerment and, ultimately, language loss is considered in regard to indigenous Ghanaian languages. It is established that two languages, namely, Ghanaian English (GhE) and Akan, especially the Twi dialect, and to a small degree, Ewe, are slowly killing off the smaller Ghanaian languages. For instance, in 1970 almost all Winneba natives spoke Efutu (Ewutu) as their first language. By 2010, 40 years later, only approximately 50% of children born to the Winneba natives speak Efutu as a first language. About 30% of these children speak no Efutu at all. Interestingly, medium-sized languages such as Ga, Dangme and Nzema are also slowly losing grounds to the three languages cited. Meanwhile there are some dozen Ghanaian languages that have less than 1000 estimated speakers each but which have held their own for a century. It is concluded that the closer a language community is to the major urban centers, the more likely it is to be endangered. It is further concluded that the language policy of the Ghana Government is contributing to the loss of Ghanaian languages.

Keywords:

Endangered, Languages, Language Loss, Ghana, Ghanaian, Ga, Dangme, GaDangme

1. Introduction

This paper takes a look at language loss in Ghana, noting the following: • What are the causes of language loss in Ghana? • Which languages are susceptible? • What is the extent of damage done? • What, if anything, can be done to curb this phenomenon? UNESCO’s (2003) Red Book of Endangered Languages, says that a language is endangered when its speakers cease to use it, cease to pass it on from one generation to another. By this definition, quite a number of languages of the world may be considered endangered. In fact, both official and unofficial linguistic data from around the world seem to indicate that in the past couple of centuries alone more than two thousand languages have been lost to mankind. Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996) claim that there are about 7,000 languages in the world today, but that there will probably be only 3,000 or so in 100 years time. They claim further that most languages are spoken by comparatively few speakers. Over half of the 7,000 languages are allegedly spoken by less than 10,000 speakers and more than a quarter of these languages by less than 1,000 speakers. These numbers are said to be too small to ensure the survival of these languages. The major languages that often threaten to swallow up the smaller ones are really very big. They include the world’s top 10, namely, Standard Chinese, English, Spanish, Bengali, Hindi, Portuguese, Russian, Arabic, Japanese, and German. Over 48% of the world’s population are said to be first language speakers of one of these languages. A number of Ghanaian linguists agree that at least a dozen of the languages lost to mankind in the past century have been indigenous Ghanaian languages. It is feared that in this (21st) century a few more indigenous Ghanaian languages will be lost. This situation is fanned by the fact that educational institutions and employers tend to reward speakers of the popular languages to the detriment of the smaller ones. Unfortunately, the issue of language endangerment (and ultimately language loss or death) is one that is not taken seriously in Ghana – not even by linguists. Research reveals that the phenomenon of language loss follows a fixed pattern. First there is language shift (either forced or voluntary), and then there is language loss. There are two suggested models. One model posits five phases which may be summarized as follows: 1. Relative Monolingualism in the indigenous language (L1). This is where all communities start, on account that no community can stay without a language. 2. Bilingualism with the indigenous language as the dominant one. 3. Bilingualism with the new/second (L2) language dominating. 4. Restricted use of indigenous language. 5. Monolingualism in the new language. The rate at which a language shifts and, ultimately, becomes endangered depends on the amount of pressure or attraction from the second language. The more pressure exerted on the L1 the faster the rate of shift. Similarly, the more attractive the L2 is to the L1 community, the faster the shift. The usual scenario, in terms of generations may be simplified as follows: • Grandparents speak only the traditional language; • parents speak both the native language and the language of assimilation, and • their children become monolingual in the assimilated language. It has been proven that the first step on the way to language endangerment and, subsequently, language loss, is cultural and linguistic assimilation. (Assimilation may be voluntary or forced.) In step two the next generation simply does not bother to learn the indigenous (first) language, mostly because it would have lost its communication value. When inter-generational transmission stops, that is the end of language. Unfortunately, this process is already at an advanced stage in the majority of urban communities in Africa. For instance, according to language data from the 1960 population census, Ga, the language of the indigenous people of Ghana’s capital, Accra, and its surroundings was the number four (after Akan, Ewe, and Dangme) in Ghana. As the city grows and as mixed marriages occur, the status of the Ga language has become questionable. In fact, current data (2000 population census) indicates that Dagbani, then the number five, has pushed Ga to the fifth position. If the current trend continues, Ga will soon be an endangered language. Interestingly, Dangme, the number three language by size, is also heading in the same direction. David Crystal (2000) points out that using population size to determine which languages are endangered and which are not does not make sense. He argues that in certain environments such as a language, the last 500 speakers of which are scattered around the fringes of “a rapidly growing city” could be considered endangered and dying. Meanwhile, in another environment (such as an isolated community) 500 speakers “would be considered quite large and stable” (pp. 11-12). He concludes that in dealing with the issue of language endangerment and language loss, researchers should never consider speaker figures in isolation. He maintains that a more important index of language endangerment is the percentage of children learning the language under consideration and using it at home. While Weinreich (1968) agrees with Crystal that census figures are only inferential. He further cautions that language shift (or in this context, language endangerment) is never abrupt enough to sever communication between age groups. He maintains that “What appears like a discrete generational difference in mother-tongues within a single family is a projection of a more gradual age-and-language transition in the community” (p. 94). He, however, agrees with other researchers that language shift is usually preceded by widespread bilingualism. Crawford (2000) states, “Along with the accompanying loss of culture, language loss can destroy a sense of self-worth, limiting human potential and complicating efforts to solve other problems, such as poverty, family breakdown, school failure, and substance abuse. After all, language death does not happen in privileged communities. It happens to the dispossessed and the disempowered; peoples who most need their cultural resources to survive.” Within the present context, this quote refers to the vast majority of Africans.

2. The Issue of Language Endangerment in Ghana

Hoffman (1999) argues that bilingualism, which is the first step in language shift, occurs when a linguistic community does not maintain its language but gradually adopts a new one. He is of the view that language maintenance succeeds only when a community makes a conscious effort to keep the language they have always used (p. 186). Following this argument, one could say that quite a number of African communities are facing a situation of language shift. As a result of the checkered history of Africa, from colonialism through neo-colonialism via coup d’etats, etc., the majority of African countries are multilingual. (This phenomenon in itself is a problem for the language teacher, especially in the urban schools who must find ingenious ways of catering for the needs of children from the various language backgrounds.) But very few of these countries have what can be remotely described as a definite (and/or sensible) language policy. This situation is not the best because a good language policy will shape the direction of language education.

2.1. Causes of Language Endangerment in Ghana

Batibo (2005) lists demographic superiority, socio-economic attraction, political dominance and cultural forces among the causes of language shift in Africa. All of these phenomena apply to the Ghanaian scene where English, the language of the colonial masters, has exerted a lot of pressure on all the local languages to the extent that a lot of children born to Ghanaians at the top of the socio-economic ladder speak only English at home. For these people, at least, English is a more prestigious and, possibly, superior language to the Ghanaian ones. In the post colonial era, the Government sought to lessen the pressure English put on the indigenous languages by selecting six regional languages to be used on radio and television. These languages of the media are Akan, Ewe, Ga, Dagbani, Nzema, and Hausa. The six languages promoted in the news media included the three geographically dominant Akan, Ewe and Hausa. (Incidentally, Hausa is not indigenous to Ghana.) This aside, nobody can be certain what criteria were used for the selection of these languages. Regardless of the circumstances, these media languages became quite prestigious, after English. Currently, Akan seems to be doing more damage to the maintenance of the other indigenous languages than English.

2.2. The Language Policy of Ghana

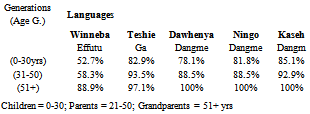

Up until the last decade or so, each child who entered school was for the first three years taught in his “native” language, with English, the lingua franca, as a subject on the school time-table. From the fourth year of school, the medium of instruction gradually changed to English such that by the seventh year of school (i.e. first year of Junior High School) all subjects were taught in English. At this point the Ghanaian language became a subject in the curriculum. This gave primary school children sufficient time to grasp the new language before being taught in it. In the past few years, however, this situation has changed. The Government of Ghana has decided to use English as the medium of instruction right from Primary One, when the majority of children know hardly a word of English. Almost all language experts consider this decision as uninformed, at best. It would seem that this new language policy of Ghana aims to alienate the Ghanaian child from its cultural heritage. And that is dangerous. Yet the Government has been unwilling to bulge on this issue. Meanwhile, there is evidence that the majority of schools, especially in the rural areas, do not even have competent teachers to implement this policy. The end result is that even the English language being taught is anything but standard. The current situation in Ghana may be likened to what linguists refer to as forced assimilation. (Depending on who is counting, Ghana may be said to have approximately 50 indigenous languages.) The situation can best be summarized as follows: To start with, English is the Second Language (L2) of all educated citizens. Where the influence of English wears off a bit the languages of the media take over. For now it seems there is a conscious effort to promote Akan over the other languages. For instance, 90% of all non-English medium programs on TV are in Akan, especially Twi. These include game shows that have people glued to the sets. The languages that are most affected are those with less than 20,000 speakers (which is almost one third of the indigenous languages). These include Ewutu-Effutu in the Central Region; Larteh-Kyerepong in the Eastern Region; Ahanta and Sewhi in the Western Region; Bimoba, Buli, Kantosi, Kusaal, Sisali, Tampulma, Chakali, Anufo and Hanga all in the Northern part of the country; and the entire cluster languages in the Volta Region labeled the Ghana-Togo Mountain Languages (namely, Avatime, Sele, Logba, Lelemi, Nkonya, Akposo, Animere, Ligbi, Krache and sekpele). Interestingly, a number of the smaller languages have resisted extinction while some of the medium-sized languages seem to be losing speakers at alarming rates. For instance, while Ga (the language of Accra and its environs) is losing grounds to Akan (see Section 1.), the number of speakers of much smaller languages such as Siwu and Logba have changed little since 1932 when Westerman first lamented their endangerment. On the other hand, Ga and Nzema are both medium-sized languages that are used in the news media but there is evidence that they are both losing grounds to Akan. The present study is an attempt to find out the extent to which some Ghanaian languages are shifting. The study focuses on a few of the smaller languages from the Central, Eastern and the Volta Regions of Ghana. Even though Ga and Dangme are medium-sized languages, they are included in this study because there is evidence that they are losing out to the Twi dialect of Akan. Similarly, Nzema is included because it seems to be losing out to the Fante dialect of Akan. Batibo summarizes the Ghanaian situation in what he terms the “typical structure of language use in an African country” as follows (H indicates dominance while L is the dominated):

3. Procedures

A set of questionnaire was used to collect data in six language communities (from three language areas) suspected to be shifting from one language to another, possibly endangering the language’s survival. The languages and communities include the Ewutu-Effutu language (Winneba), the Ga language (Teshie – Accra), the Dangme language (Dawhenya – Prampram, Ningo, Sege – Ada, and Kasseh – Ada). The four Dangme-speaking communities (i.e. Dawhenya, Ningo, Sege and Kasseh) were included based on their distances from cosmopolitan Accra.

3.1. Selection of Languages and Language Communities

Selection of the language communities was based on two assumptions. First it was assumed that the language of a community that has a large proportion of immigrants that come from a different language background is likely to be endangered. Weinreich (1968 p.91), for instance, indicates that “since many immigrant groups have a significantly low proportion of women among them, the necessity for intermarriage leads to a discontinuity of linguistic tradition.” Similarly, it was assumed that the closer to Accra (Ghana’s capital and major cosmopolitan city) a language community is, the more endangered that community is likely to be. This is due to the fact that currently, Ghana is faced with a major rural migration problem where all the migrants are heading for Accra or Kumasi, the second most important business center. Based on these assumptions, the following communities were selected. Awutu-Effutu is the language spoken by the indigenous people of Awutu, Senya, and Winneba, all in the Central Region of Ghana. Winneba, a mostly fishing community on the coast some 50 kilometers due west of Accra, is the home of the Effutu dialect of this language. The community is surrounded by Akan (in particular, Fante) settlements. Approximately 50 years ago, the township embarked on a steady growth when Ghana’s first President, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah established the Ideological Institute used in training ‘freedom fighters’. In the past 20 years or so there has been major incursion of immigrants from other parts of the country as a result of the establishment of the country’s only purely teacher training university. The official languages studied in the local basic schools are English and Fante, the main language of the Central Region. The local radio station does almost all its programming in Fante, allowing only one slot of Effutu on Tuesday afternoons. The 1990 Ghana Census figures estimate that there are approximately 100,000 speakers of the combined dialects of Awutu-Effutu. This is not a literary language. Winneba is a small fishing town of Effutu-Awutu speakers in the Central Region of Ghana. The town, which is almost surrounded by Fante speaking towns, is currently the home of a major national university. During each school semester, the number of non-natives outnumbers the indigenes. Ga-Adangme-Krobo is the indigenous language of the people of the Greater Accra Region as well as some of the eastern parts of the Eastern Region of Ghana. The 1990 population census estimates that there are approximately 1,250,000 speakers of this language, making it the third largest indigenous language (after Akan and Ewe). Dangme speakers (i.e. Adangme and Krobo) clearly outnumber Ga speakers, who are estimated to be a little over 300,000. While Ga and Dangme are mostly mutually intelligible, they are separate official literary languages. Teshie is a popular suburb of Accra, the capital of Ghana. Initially, this was a community of Ga speakers only. Like Winneba, the area is now home to a lot of Akan and Ewe speakers. Additionally, speakers of almost all the Ghanaian languages can be found in this part of Accra as they find housing not too far from their jobs in the city center. Teshie is approximately 20 kilometers from downtown Accra. Dawhenya, which until about twenty years ago is a small settlement on the Accra-Ada-Togo highway, is one of the fastest growing townships in Ghana. All its inhabitants used to be Dangme speakers from Prampram and Ada. As housing shortages hit the harbor city of Tema, some 20 kilometers to the west, more and more workers began to build houses there. The establishment of the church-owned Central University College three kilometers to the east of this settlement has caused the population to double in less than six years. The majority of new settlers are Akan speakers. Dawhenya is approximately 55 kilometers from downtown Accra. Ningo is an old settlement of Dangme speakers. It is almost six hundred years old. In the past thirty to fifty years Ningo has been an important fishing town where fishmongers from the Accra-Tema megapolis go to buy fish. While the majority of fishmongers are Ga- or Dangme-speaking, a number of them are speakers of the Akan language. The majority of these people commute to the township on a daily basis. The settlement is approximately 70 kilometers from Accra. Kasseh-Ada began as a small market town on the Accra-Togo highway. It also happens to be the main turnoff to Big Ada and Ada-Foah, the two principal towns of the Ada State. On market days (i.e. Tuesdays and Fridays), the town is flooded with traders from many southern Ghana towns. The majority of commuters on these two days are from Accra and Aflao, a major Ewe speaking town on the Ghana-Togo boarder. Kasseh is approximately 110 kilometers from Accra.

3.2. The Respondents

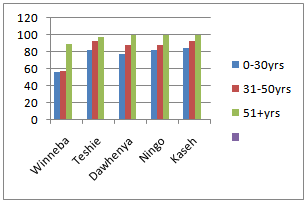

Members of the communities were categorized into age groups as follows: • 01 – 10 years (corresponding to Children) • 11 – 20 years (corresponding to Children)• 21 – 30 years (corresponding to Parents?)• 31 – 40 years (corresponding to Parents)• 41 – 50 years (corresponding to Parents)• 51 – 60 years (corresponding to Grandparents)• 61 yrs & above (corresponding to Grandparents)

3.2.1. The Effutu (Winneba) Correspondents

Members of the communities were categorized into age groups. The Winneba communities are as follows: a) Children: 0 – 10 years (10 respondents) 11 – 20 years (61 respondents) b) Parents: 21 – 30 years (41 respondents) 31 – 40 years (38 respondents) 41 – 50 years (34 respondents) c) Grand Parents: 51 – 60 years (18 respondents) 61 years and above (18 respondents) Table 1 presents the members of the various communities by age groups. For children under six, mothers provided answers to the questions. This age group was quite important to the study in that it provided data for the extreme end of the spectrum. | | Age | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | 0 – 10 | 10 | 27 | 9 | 18 | 8 | | 11 – 20 | 61 | 59 | 35 | 15 | 26 | | 21 – 30 | 41 | 31 | 20 | 19 | 40 | | 31 – 40 | 38 | 28 | 17 | 8 | 24 | | 41 – 50 | 34 | 18 | 9 | 14 | 18 | | 51 – 60 | 18 | 22 | 5 | 5 | 9 | | 61+ | 18 | 13 | 5 | 14 | 18 | | TOTAL | 220 | 198 | 100 | 93 | 143 |

|

|

3.3. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire comprised twenty-three mostly multiple choice questions modified to suit each language community. (Please see Appendix 1.) Question 1 sought to find the appropriate age group of the respondents. Question 2 sought to establish which parent was an indigene of the language community. Questions 3 to 8 sought to establish the languages spoken by the respondents as well as the order in which they were acquired. Question 9 asked the respondent to self-asses his/her language proficiency. Questions 10 to 23 sought to establish language usage in the respondents’ environment. The questionnaires were distributed to the appropriate age groups in the communities cited in 3.1 together with the following instructions: “The following questionnaire is to enable us collect data on language use in Ghana. Your responses will be used for educational purposes only. Any information you give will be treated as very confidential. Kindly respond to the questions by ticking the appropriate space in the boxes provided as follows. Thank you for your cooperation.” Where the subject was not literate in English, a third person was employed to assist in filling out the forms. For children under six, mothers provided answers to the questions. This age group was quite important to the study in that it provided data for the extreme end of the spectrum.

4. Findings

The results of the study are presented here under the following headings: • How many Ghanaian languages do you speak? • Which Ghanaian Languages do you speak? • Which Language did you learn to speak first?• Which language do you use mostly at home? • Which of these Languages do you use most often?

4.1. How Many Ghanaian Languages Do You Speak?

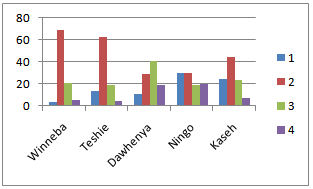

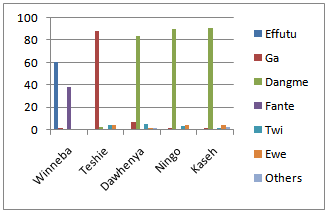

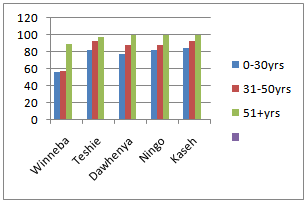

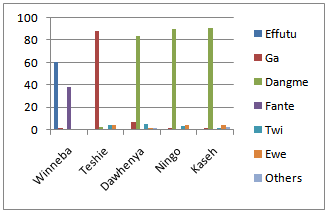

This question was designed to establish the ratio of monolingual to bilingual speakers among the communities under study. It is quite clear from the data presented in Table 2 (see also Figure 1) that the vast majority of the people living in Winneba (i.e. 96.4%) speak at least two languages. By far, the largest number of people (69.5%) speaks two languages. For all practical purposes, therefore, Winneba can be referred to as a bilingual society. With the exception of subjects aged 61 and above, where the majority tends to speak three languages, this observation holds true within the age groups as well. Data from the Ga-Dangme areas seem to point in the direction of bilingualism as well, though this phenomenon is not as pronounced as in the Winneba area. The Teshie figures, for instance, indicate that 86.4% of the people speak two or more languages. As with Winneba, by far, the largest number of Teshie people (62.6%) tends to speak two languages. The picture is not that simple in the Dangme speaking communities. In the Dawhenya community, for instance, the largest single group is trilingual with 41% of the population, while in the Ningo community there are equal numbers of monolinguals and bilinguals (30.1%). In the Kasseh community, the bilinguals clearly have an edge over the others at 41%. Note, however, that bilingualism seems to increase as one goes up the age ladder. It would seem that GaDangme speakers tend to acquire additional languages later in life. Teshie seems to be an exception to this phenomenon in the sense that the majority of people above 60 years are monolingual in Ga (i.e. 53.8%) while only 22.2% of children up to 10 years old are monolingual. | Table 2. Number of Languages spoken, per community, expressed in percentages |

| | No. Lags | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | 1 | 3.6% | 13.6% | 11% | 30.1% | 24.5% | | 2 | 69.5% | 62.6% | 29% | 30.1% | 44.1% | | 3 | 20.9% | 19.2% | 41% | 19.4% | 23.8% | | 4 | 5.5% | 4.6% | 19% | 20.4% | 7.7% |

|

|

| Figure 1. Number of languages spoken per community, expressed as percentages |

4.2. Which Ghanaian Languages Do You Speak?

This Question sought to establish the actual Ghanaian languages that are used in these communities. Results of this exercise are presented in Table 3. In Table 3, it is established that the vast majority of people living in Winneba (94%) speak Fante in addition to Effutu. A quarter of these people (24.5%) actually speak a third language in addition to Effutu and Fante. Interestingly, apart from two infant monolinguals, the only other Effutu speaking monolingual is in the 61 years and over age group. All the other monolinguals in the Winneba community use Fante rather than Effutu. In the Teshie Community, the most popular languages are Ga and Twi. In fact, as many as 66.2% of the indigenes speak Twi in addition to Ga. The single largest group is those who are bilingual in Ga and Twi (49.5%). Like Teshie, the Dawhenya community also prefers Twi as a second language in that a hefty 73% speak Dangme and Twi. The two other Dangme speaking communities display healthier ratios of monolingual to bilingual speakers. For instance, the monolingual Dangme speakers in Ningo form 30.1%; and in Kasseh the monolingual Dangme speakers represent 20.3% of the Community. While Twi was the second most popular language in most of the Dangme communities, it was replaced by Ewe in the Kasseh Community where 39.2% of the Community spoke Ewe in addition to Dangme. In terms of monolingual usage, almost all monolingual speakers in the Ga and Dangme areas use the indigenous languages. There are a few exceptions including one person in Kasseh who is monolingual in the Ewe language. | Table 3. Languages spoken in the Community expressed in percentages |

| | Language | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | Effutu | 1.4% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ga | -- | 13.1% | -- | -- | -- | | Dangme | -- | -- | 9.0% | 30.1% | 20.3% | | Fante | 3.2% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Twi | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ewe | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2.1% | | Effu & Fan | 93.6% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Fan & Othrs | 1.8% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ga & Dang | -- | 8.6% | 68.0% | 23.7% | 20.3% | | Ga & Twi | -- | 66.2% | -- | 5.4% | -- | | Ga & Othrs | -- | 28.8% | -- | -- | -- | | Dang & Twi | -- | -- | 73.0% | 28% | 32.2% | | Dang & Ewe | -- | -- | -- | 6.4% | 37.1% | | Dang & Othrs | -- | -- | 9.0% | 6.5% | -- |

|

|

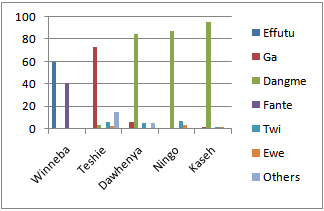

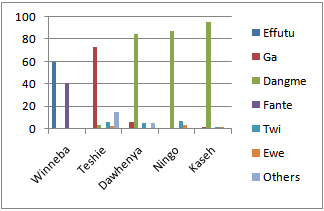

4.3. Which Language Did You Learn to Speak First.

Answers to the question ‘Which language did you learn to speak first’ are presented in Table 4 and Figure 3. The question was designed to establish the first language (L1) of members of the various communities. | Table 4. Language First spoken by members of the Community expressed in percentages |

| | Language | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | Effutu | 60.5% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ga | 1.4% | 87.9% | 7% | 2.2% | 1.4% | | Dangme | -- | 2.5% | 83% | 89.2% | 90.2% | | Fante | 37.7% | -- | 1% | 1.1% | -- | | Twi | 0.5% | 4.0% | 5% | 3.2% | 1.4% | | Ewe | -- | 4.5% | 2% | 4.3% | 4.2% | | Others | -- | 1.0% | 2% | -- | 2.8% |

|

|

Table 4 reveals that for the majority of people in the Winneba community (60.5%), Effutu is indeed the first language acquired. This is followed by Fante (37.7%) Interestingly, the numbers fall as one goes down in age. For instance, while approximately 90% of people in the grandparent group learned Effutu first, Less than 50% of those in the children group learned Effutu first. Results of the GaDangme communities indicate that the overwhelming majority of indigenes acquire Ga and Dangme as their first languages, starting from as much as 90.2% for Kasseh Dangme to a low of 83% for Dawhenya Dangme. The other Dangme Communities are as follows: 89.2% for Ningo, and 87.9% for Teshie Ga. Surprisingly, Ewe turned out to be the second most popular first language acquired in almost all the GaDangme speaking communities. Dawhenya, where Twi came in second, is the only exception.  | Figure 3. Language first spoken by members of the community expressed percentages |

4.4. Which Language Do You Use Mostly at Home?

This question seeks to establish the language used in the home environment. Answers from the various communities are shown in Table 5 and Figure 4. | Table 5. Languages mostly spoken at home expressed in percentages |

| | Language | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | Effutu | 59.5% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ga | -- | 72.7% | 6% | 1.1% | 1.4% | | Dangme | -- | 3.5% | 84% | 87.1% | 94.4% | | Fante | 40.5% | 1.0% | -- | 1.1% | -- | | Twi | 0.5% | 5.6% | 5% | 6.5% | 1.4% | | Ewe | -- | 2.5% | -- | 3.2% | 2.1% | | Others | 0.9% | 14.6% | 5% | 1.1% | 0.7% |

|

|

| Figure 4. Languages mostly spoken at home expressed in percentages |

In the Winneba community, the question ‘Which language do you use mostly in your home?’ indicated that 59% of the people tend to use Effutu in the house. This is followed by 39% of those who use Fante. In fact, the data indicates that the older people are more likely to use Effutu (77.8%) than Fante (22.2%), while the children tend to give equal time to Effutu and Fante (see Figure 4). In the Teshie community, as many as 72.7% of the people claim to use Ga at home. This is followed by English and Twi at 14.6% and 5.6%, respectively. Results from the Dangme communities are not very different from those of Teshie. In all cases, Dangme was the language of choice in the home (Dawhenya = 84%; Ningo = 87.1%; and Kasseh = 94.4%). In terms of a second language for the Dangme homes, the results are mixed. The Dawhenya community preferred Ga (6%), closely followed by Twi and English (5% each). The Ningo community prefers Twi (6.5%), while Kasseh prefers Ewe (2.1%) followed by Twi.

4.5. Which Language Do You Use Most Often?

Answers to the question ‘Which language do you use mostly in the home?’ are shown in Table 6 and Figure 5. While question four seeks to establish the language used in the home environment, question five seeks to establish the language used most often inside and outside the home. Not surprisingly, the language used most often by the Effutu people of Winneba is Fante (72.9%). Quite surprisingly, only about 10.7% of the children category (ages 0-30) use Effutu as their primary language of communication, leaving a hefty 93% that use Fante primarily (Table 5). Clearly, the Winneba community may be described as being a bilingual one with the new language (Fante) dominating. | Table 6. Languages most often spoken in the Community expressed in percentages |

| | Language | Winneba | Teshie | Dawhenya | Ningo | Kaseh | | Effutu | 26.8% | -- | -- | -- | -- | | Ga | -- | 86.9% | 5% | 2.2% | 10.7% | | Dangme | -- | -- | 82% | 82.8% | 95.1% | | Fante | 73.2% | 0.5% | -- | 1.1% | -- | | Twi | -- | 6.6% | 9% | 8.6% | -- | | Ewe | -- | 2.0% | -- | 4.3% | 2.8% | | Others | -- | 4.0% | 4% | 11.1% | 1.4% |

|

|

| Figure 5. Languages most often spoken in the Community expressed in percentage |

The Teshie respondents overwhelmingly claim Ga as the language used most often in and outside the home. Interestingly, however, among the children’s category the figure stands at 91.4% while the parents and grandparents categories claimed 100% Ga usage. In the Dangme communities the situation is as follows: 82% of people in Dawhenya use Dangme most often, followed by 9% who use Twi; 82.8% of people in Ningo use Dangme most often, followed by 8.6% who use Twi; followed by 3.3% who use Ga; and 95.1% of people in Kasseh use Dangme most often, followed by 2.8% who use Ewe. It is evident that unlike the situation in Winneba, the GaDangme communities can only be described as bilingual communities with the indigenous language being the dominant one.

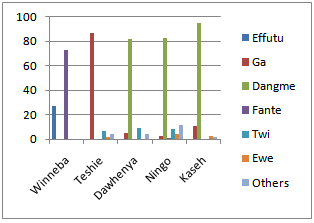

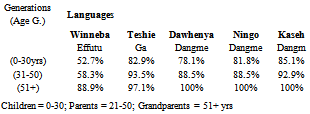

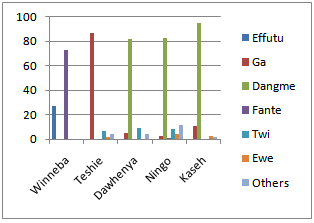

5. Discussion of Results

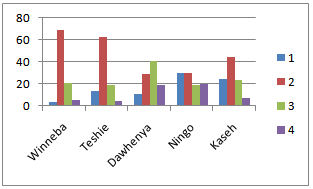

This Section is an attempt to discuss the current data in relation to the scenario presented in Section 1.0 regarding language endangerment and, ultimately, loss. It has been suggested that in terms of the generations, the usual trend is as follows: • Grandparents speak only the traditional language; • Parents speak both the native language and the language of assimilation, and • Their Children become monolingual in the assimilated language. Answers to the question “Which of these languages did you speak first?” indicate that there are definite signs of language shift in all the communities under study. The rate of shift varies from one community to another. In terms of first language acquisition across the generations, the situation is as indicated in Table 7 and Figure 6. Table 7. Percentage of Indigenes that Acquire the Traditional Language as L1

|

| |

|

The pattern clearly indicates language loss through the generations. The details of this phenomenon are discussed in the sections below.

5.1. The Awutu-Effutu Language

Of the six communities under study, the Effutu dialect of the Awutu-Effutu language is clearly the most endangered. Less and less indigenous Winneba children are acquiring Effutu as a first language, opting instead for Fante. Similarly, Fante seems to be the language of choice in these children’s environment (home, school, church, etc.). The fact that the indigenes are clearly outnumbered by the immigrants will seem to be responsible for this phenomenon. Clearly, Effutu is losing grounds to Fante. Winneba children are not using the Effutu language because some parents prefer speaking to their children in Fante rather than the indigenous language. The end result is quite predictable. It leads to language death. It will not be unfair to say that the language may not be around in the next century. With the demise of the language, the culture of its people also dies with it. This further leads to loss of resources, including opportunity for the scientific study of human speech communication.

5.2. The Ga-Dangme Language

As far as the Ga language is concerned, Table 7 indicates that the Teshie community also shows a trend towards language shift though the phenomenon is not as radical as that of the Winneba community. This is understandable in the sense that the community is lodged in the center of other Ga-speaking communities. The pressure from non-Ga-speaking immigrant families is quite remarkable. In fact, there are non-Ga-speaking tenants in almost every household. | Figure 6. Percentage of indigenes that acquire the traditional language as L1 |

Data from the Dangme communities indicate that only two generations ago, everybody in these communities acquired Dangme as a first language. This situation is gradually changing such that about one generation ago 88.5% of Dawhenya, 81.8% of Ningo, and 92% of Kasseh spoke Dangme as a first language. Compare this with the current generation where only 78% of Dawhenya, 88.5% of Ningo and 85% of Kasseh acquired Dangme as a first language. The current trends in language acquisition clearly point to the process of language shift. There is no doubt that Ga and Dangme are both losing grounds to Twi and Ewe. There is reason to worry about the situation in Dawhenya, in particular. This is because in the past five years a major university campus has been located in this hitherto small farming settlement. With the establishment of the campus came an influx of many non-Ga-Dangme speakers into the community. The majority of these newcomers are Twi-speaking followed by Ewe speakers. The current trend indicates that in the next 10 years, the indigenous Ga-Dangme people will form less than half of the population of the community. This is comparable to the situation that the Effutus of Winneba are in at the moment. The results of the Effutu study are not very different from the data that has been collated thus far from the other language communities under study. The language situation in these communities can best be described as diglossic, since the people often use a second language (mostly Twi, Fante or Ewe) in the official aspects of their lives such as, education, business and, sometimes, even religion while relegating the indigenous language to the homes. When one considers the fact that most of the indigenous languages are not the languages of choice even in domestic activities, one can see the extent of the threat. All indications are that Ahanta and Nzema are both losing grounds to Fante. Larteh and Kyerepong seem to be losing grounds to Twi. Ga and Dangme are both losing to Twi. The situation in the Togo-Mountain languages, namely Avatime, Logba, Santrokofi, Siwu and the others, is a complex one that will be examined in a forthcoming paper. Mostly, Ewe is putting pressure on the languages in the southern parts of the mountains while Twi is exerting pressure on those in the northern parts. In a few cases, however, pressure is being exerted by both Twi and Ewe on the same language. Somehow, the number of speakers have not changed much since 1922 when Westermann first brought the plight of these languages to public attention. It is possible that the highlands that enclose these communities and which prevent constant influx of non-indigenes may be responsible for this paradox. Crystal’s argument, cited earlier in Section 1, about number of speakers would be certainly quite appropriate here in the sense that these are isolated communities. The Nzema situation is another complex one in the sense that it is taught all the way to the tertiary level and also serves as one of the six media languages. These two facts notwithstanding, it is still being threatened by Fante. A more detailed study than the present one is underway to determine the nature of this language shift. It is important to point out that as surprising as the Nzema situation is the one of Dangme, the language that is ranked third by population size of indigenous speakers. Apparently, in this case, the attitudes speakers play a larger role in the perceived language shift than any other phenomenon. This situation contrasts very sharply with that of a few of the Togo-Mountain languages that have remained in use nearly two centuries after they had been cited with less than six thousand speakers each. These two contrasting situations will be given more attention in the next paper. Obviously, the fact that a language has a large number of indigenous speakers does not really matter as far as language endangerment is concerned.

6. Conclusions

The situation in the Ga and Dangme communities indicates that less and less children in the peri-urban communities are acquiring the traditional languages as a first language. The results also indicate that the closer a community is to an urban center, the less likely it is for its children to acquire the indigenous language. The Effutu data (and to some extent the Dangme data from Dawhenya) adds a different dimension in the sense that the indigenes are being displaced by a neighboring language. Evidently, a lot of the indigenous languages of Ghana are in danger and could even be lost in the next few generations. The question then is, “What measures should we put in place to curb this trend?” A number of solutions come into mind. These include taking another look at the country’s language policy as well as reviewing the choice of “media languages”. All in all, a conscious effort must be made by all concerned to maintain the various languages. But a lot depends on the native speakers themselves who must be emotionally attached enough to be willing to stand up for their native languages. (Weinreich labels this phenomenon as “Language Loyalty” and equates it to “Nationalism”.) For language educators such as the present authors, the task becomes quite challenging. Special efforts could be made by this category of Ghanaians to run short programs in a number of endangered Ghanaian languages such as Efutu. In the absence of any comprehensive language maintenance plan, efforts must be made to keep adequate linguistic records of the smaller languages of Ghana. That is all that may remain behind when the present trend is allowed to run its course. The authors intend concentrate the next phase of the research on the Ahanta and Nzema area because the Region (Western Region) is the one that is currently recording the fastest population growth as a result of recent offshore oil find and subsequent drilling. Since these, especially Ahanta, are smaller languages to start with the sudden influx of people from other language communities (led by Akan) is expected to have negative impact on their maintenance. The Ga-Dangme people of Ghana boast of some of the world’s richest culture, including the quite elegant so-called “six-cloth” wedding ceremony. Like the Ga-Dangme people, a number of the language communities under study have beautiful cultures that are show-cased on the Country’s TV programs as well as tourist literature. Considering the fact that language loss is always accompanied by loss of the culture, it behooves all well meaning Ghanaians and linguists, in particular, to do all they can to prevent the extinction of the country’s endangered languages.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge all those who contributed in diverse way towards the completion and write-up of this study, in particular, Dorothy Afo Mensah who collected the bulk of the Effutu data in this study. The Teshie data was collected by Martha Akuorkor Doku, while the Kasseh data was the provided by David Dakeh Oha-Akpanglo. The study could not have materialized without funding from the following organizations: Carnegie Corporation of New York grant B7693 and World Bank (TALIF) grants UEWS/1/001/2004 and UEWR/4/004/2006.

References

| [1] | Akpanglo-Nartey, Jonas N., Rebecca A. Akpanglo-Nartey, Emmanuel N. A. Adjei, Dorothy Afo Mensah, Pascal Kpodo (2008) “Language Loss Among Indigenous Ghanaian Languages.” Papers in Applied Linguistics. No. 2 pp. 333-343. Winneba, UEW Press. |

| [2] | Akpanglo-Nartey, J. N., (2002) An Introduction to Linguistics for Non-Native Speakers of English. 2nd Edition. Tema: SAKUMO Books |

| [3] | Batibo, H. M. (2005) Language Decline and Death in Africa: Causes, Consequences and Challenges. Clevendon: Multilingual Matters. |

| [4] | Blench, R. (1998) The Status of the languages of Central Nigeria. In M. Brenzinger (ed.) Endangered languages in Africa, pp. 187-206. Kohn Rudiger Koppe Verlag. |

| [5] | Crawford, James (2000) “Endangered Native American Languages: What Is to Be Done, And Why?” http//ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/JWCRAWFORD/brj.htm. |

| [6] | Crystal, David (2000) Language Death. Cambridge: University Press. |

| [7] | Dimmendaal, G. J. (1989) On language death in Eastern Africa. In N. Dorian (ed.) Investigating Obsolence: Studies in Language Contraction and Death. Cambridge: University Press. |

| [8] | Fishman, J. A. (1999) Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity. Oxford: University Press. |

| [9] | Giles, H., Bouris, R. and Taylor, D. M. (1977) Towards a Theory of Language in Group Relations. New York. Academic Press. |

| [10] | Hoffman, C. (1999) An Introduction to Bilingualism. London: Longman. |

| [11] | Kuncha, M. & Bathula, H. (2004) ‘The Role of Language Shift and Language Maintenance in a New Immigrant Community. A Case Study.’ Working Paper No. I: 1-8. |

| [12] | Ladefoged P. (1964). A Phonetic Study of West African Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| [13] | Ladefoged, P. & Maddieson, I. (1996). Recording the phonetic structures of endangered languages: UCLA Working Paper in Phonetics, No 93; pp. 1-7. |

| [14] | Smieja, B. (2002) Language Pluralism in Botswana: Hope or Hurdle? Frankfurt: Peter Lang. |

| [15] | UNESCO (2003a). Red Book of Endangered Languages: Africa. Tokyo: International Clearing House for Endangered Languages (ICHEL). |

| [16] | UNESCO (2003b). Language Vitality and Endangerment. |

| [17] | Veltman, C. (1983) Language Shift in the United States. Berlin: Mouton. |

| [18] | Visser, H. (2000) Language and Cultural Empowerment of the Khoesan People. The Naro Experience. In H. M. Batibo and B. Smieja (eds.) Botswana: The Future of the Minority Languages. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 193-215. |

| [19] | Weinreich, Uriel (1968) Languages in Contact. The Hague: Mouton. |

| [20] | Westermann, D. (1922). Vier Sprachen aus Mitteltogo: Likpe, Bowili, Akpafu und Adele, nebsteinigen Resten der Borosprachen. Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen, 25:1-59. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML