-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Library Science

p-ISSN: 2168-488X e-ISSN: 2168-4901

2020; 9(4): 84-96

doi:10.5923/j.library.20200904.02

Received: Jul. 12, 2020; Accepted: Aug. 15, 2020; Published: Aug. 29, 2020

Perception, Sources and Types of Antenatal Information Dissemination Among Pregnant Women in Semi-Urban Area: A Qualitative Case Study

Yani S. D.1, Abdullahi M. I.2, Gbaje E. S.1, Gammaa H. I.3

1Federal University Lokoja, Lokoja, Kogi State

2Kaduna State University, Kaduna, Kaduna State

3Department of Nursing Science, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State

Correspondence to: Yani S. D., Federal University Lokoja, Lokoja, Kogi State.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study is a phenomenographic of perception, sources and type of antenatal information disseminated among pregnant women in semi-urban area to respond with empirical measures to prevent mortality of pregnant women and improve live birth. Participants’ selection was based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of fifteen pregnant women were purposively selected, and using a data redundancy/saturation techniques they were administered semi-structured interview and the researcher facilitated by non-participant observation collected data on set of predetermined open-ended questions and those that emerged from the dialogue. The interpretative paradigm was explored and utilised during the quantitative content analysis strategy to condense raw data into categories for the final analytic inductive purposes. A total of 197 open codes emerged from the narratives of participants but collapsed eventually into related subcategories for each of the study’s objectives. Results on perception revealed that pregnant women subcategorised four levels of perceptions that accounted for 93.66% of perceived antenatal information to be alien, new, contradicts culture, religion and expensive. On sources of antenatal information, two categories emerged and accounted for 100% of decision making into related issues of family planning, pregnancy complication and getting pregnant. These were sourced from social network and internet. On types of antenatal information, four categories emerged and accounted for 100% influencer of improved healthcare. It was recommended that antenatal information should be broken down into smaller packages that can guide the impulse of pregnant women who receive and disseminate antenatal information formally and informally.

Keywords: Antenatal information, Live birth, Mortality, Perception, Phenomenographic study

Cite this paper: Yani S. D., Abdullahi M. I., Gbaje E. S., Gammaa H. I., Perception, Sources and Types of Antenatal Information Dissemination Among Pregnant Women in Semi-Urban Area: A Qualitative Case Study, International Journal of Library Science, Vol. 9 No. 4, 2020, pp. 84-96. doi: 10.5923/j.library.20200904.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Antenatal information is a huge package with several compartments beneficial to health workers, health research, expectant mothers, delivered mothers, delivered child and their families. Arguably because of the need to put an end to the over 303,000 women who die each year from pregnancy-related cases globally [1,2]. Unfortunately, Africa and South Asia account for 88% of these maternal deaths; Nigeria loses approximately 814 women per 100,000 live births [3]. Reasons advanced for the causes of maternal death comprise lack of education [4], lack of motherly care [5], economic disparity [6], and depression, self-withdrawal, hopelessness, shock and traumatic experience [7]. The consequence of maternal death is reiterated by numerous conventions and institutions on healthcare and services. For instance, the fourth and fifth goals of the Millennium Development Goals proposed reduction of child mortality and improve maternal health [8]. In specific terms the Sustainable Development Goals proposed reduction of mortality to less than 70 death per 100,000 live birth through good health and well-being (article three) [9]. Of the numerous institutionalised mechanisms, the antenatal care and information services have been emphasised as most potent. These two which come as a package of related health programme to reduce pregnancy related mortality. The efforts and demonstrations by World Health Organisation through intensification to reduce pregnancy mortality is recorded from the training it fund for the capacity building of front lines caregivers and the other chains in the sectors, particularly midwives and doctors. On the other hand UNICEF is funding yearly emergency obstetric care, supporting and sensitising healthcare beneficiaries on the benefits of good prenatal care as well as training medical personnel on measures that can prevent mother-to-child diseases transmission and girl-child education.Despite these interventions and supports pregnancy related deaths remain high. This study is not far away from others that focus on the importance of antenatal health care services that is seeking to contribute from different perspectives by what ways the scourge could be addressed. The paper is mindful of studies from the medical perspectives [10], and focused on the sociological implications [11], yet the problem seems unabated. A promising approach is to understand the perception, sources and types of antenatal information accessed by pregnant women using General Hospital Kafanchan as a case study. The assertions was based on the premised that perception, sources and types of antenatal information constitute a crucial element of medical care that influence decision taking that directly affects the quality and outcomes of healthcare services and could address setbacks such as ignorance. Even though the amount of information accessible by patients has been topic of speculation in the medical field pre-the internet era [12].Kafachan is a semi-urban centre in the southern part of Kaduna State, historically it is commercial suburb because of the railway station which attracted people from within and outside the country to settle their. This makes the town transformation from the rural to semi-urban centre very rapidly. General Hospital, Kafanchan is located in Jama’a Local Government Area of Kaduna State. It is a state government hospital that provides variety and specialized healthcare services at a minimal cost. It provides both out and in patient services which include, antenatal and delivery services, attends to a large number of different healthcare cases annually, and has a good record of well-trained medical personnel in medical fields. For antenatal, service is provided on scheduled monthly, fortnightly, and weekly as the pregnancy progresses. The location of the service is the Antenatal unit of the hospital. The service format or procedure is through verbal discussions with the group of pregnant females who have come for the service. The personnel providing antenatal service to the pregnant women are the nurses. With a fertility rate of 6.7 compared to the national figure of 5.7, it is imperative that such strategic location in the north-west geopolitical zone of Nigeria could provide answers to questions on ways to resolve high mortality rate in the region and country at large [13,14].

1.1. Research Objectives

- 1. determine the perception of pregnant women towards antenatal information in Kafanchan General Hospital, 2. examine the sources of antenatal information among pregnant women attending Kafanchan General Hospital, and 3. Find out the types of antenatal information utilised by pregnant women attending Kafanchan General Hospital

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perception of Pregnant Women Towards Antenatal Information

- According to Galle, Van Parys, Roelens and Keygnaot [15], perception of pregnant women towards antenatal information could be used as a measure of quality extent that expected healthcare needs are met. However, the capacity of pregnant women to make choices as a result of the opportunities availed them by the antenatal information carrying channels has significantly improved. Nevertheless, Prudêncio, Messias, Mamede, et al. [16] attested that perception of pregnant women towards antenatal information is influenced by experience, social, and cultural norms, women demographics, and the extent of the knowledge of what should be expected.Studies that consider these factors when investigating perception has yielded positive and consistent findings concerning pregnant women willingness to participate and adhere to the rules and regulations stipulated in these healthcare guidelines. This may not be said about the rural areas where some reports have revealed that antenatal information are influenced by what constitute community belief, norms and adaptable pattern that are prescribed for pregnant women as the healthcare behaviour that they must follow or be stigmatised. It is clear that the community do not live in isolation in these areas and the decisions made by a pregnant woman is influenced by those around them and not the advice from experts of the healthcare centres [14].

2.2. Sources of Antenatal Information by Pregnant Women on Healthcare Services

- Information about pregnancy, birth and partum period are basic needs that sources of antenatal information provide. Source of antenatal information have consistently helped pregnant women to explore each stage and state of pregnancy [17]. According to Grimes et al. [17] these sources of antenatal information help during the transition to safe delivery, parenthood for those that it is the first baby, equip families prepare for the prospective expectations, and adjustments to the new life roles. Sources of antenatal information comprised clinics, midwife, pamphlets, internet, books, friends, family and doctors (obstetrician). These sources influence decisions surrounding pregnancy, birth and partum period.Corolan [18] and Shieh et al. [19] in their separate submission attested that the ability of a pregnant woman to have her information needs met is depended by access such woman has to different sources of information and her ability to comprehend such information. In other words, when a pregnant woman is complaisant to antenatal healthcare, first, the sources of information have multiple positive effects to care of her pregnancy as she is convinced that there is some forms of physical feedback and not alien with the education provided in form of training on care of mother and unborn child. Secondly, that the sources provide messages that are understood and provides clearer answers to areas she finds difficult to comply with and as instructed. Thirdly, regardless of literacy skills, sources of antenatal information has helped the woman and her family understand the state of healthcare during pregnancy and include the family members to actively participate in decision making disposed to pregnant women from reliable sources of information. Lastly, the quality of pregnant woman healthcare can be traced to the source of information at her disposal. Therefore advancing discussions on the sources of information could guide these women to fruitfully make sense and ensure they don’t “stand alone” when retrospection becomes inevitable and when they need clarification.The internet has become increasingly a source of diverse types of written healthcare information [20]. The extent to which it influence pregnant women take decision is unclear [17], but there are attributes of the internet that show the tendency that women who use it do so to acquire numerous types of health care information [21], this is not to say that pregnant women generally are involved, some prefer traditional sources of healthcare information during the transition and after the transition period of pregnancy [19]. This implied that, it is increasingly difficult to have a comprehensive information list of available sources of antenatal information that women preferred or use (about the relative merit of these various sources) [17].

2.3. Types of Antenatal Information Utilised by Pregnant Women for Healthcare During Pregnancy

- The thrust on types of antenatal information in numerous literature document followed formal documentation pattern such as grey, peer review, chapter in book, books, monograph, website, blogs and pamphlets, but in most rural areas antenatal information utilized by pregnant women are through word of mouth. Incidentally, the formal types of antenatal information have helped these studies to review themes, similarities and differences in terms of messages and audience. It has also been an avenue for the synthesizing of the types antenatal information in terms of compliance with statutory test, treatment, health promotion activities and supportive measures [22].According to Ebijuwa, Ogunmodede and Oyetola [23] the type of information made accessible to pregnant woman at any given period influences the quality of decision they make. Pregnant women therefore need education about the different types of antenatal information sources. A study by Lau et al. [24] opined that the use of short message service (SMS) as a type of antenatal information and for healthcare services could provide guide, the type of information conveyed (topics) categorised by their peculiarities and target recipients to bridge the information gaps in healthcare services. That the character should not exceed 160 makes the information conveyed precise. Earlier, Simoes et al. [25] reported that type of antenatal information courier is influenced by demographics of pregnant woman. According to Chote et al. [26] lack of job and the type of occupation of a pregnant woman relate to the inadequacies of use of different types of antenatal information.

3. Theoretical Framework

- To explain and make prediction of the patterns of pregnant women towards the Weick’s sense making theory was adopted to facilitate understanding of data collected and their relationships. This theoretical frame was also to help operationalise the role of antenatal information to reduce pregnancy related mortality as well as to clarify and make constructs used to appreciate the fight against none use of antenatal information availed pregnant women in the study area.The choice of Weick’s sense making theory was the deliberate approach it could facilitate understanding of factors that aid decision making using available information. The pivot of the theory is providing basis for the interpretations that could guide actions obtained from individuals, and perhaps starting from when there is an attempt to justify action and events [27,28]. In other words, the theory presumes that individuals construct meaning from cues that do or do not mesh with established understanding. Therefore, use or non-use of information is dependent on the narratives that Weick referred to as “frame”. The frame created as a result of socialisation which help shape perspective (cues) as part of sense making.Predictable pattern consists of those who make positive sense of information are those who use information at their disposal, while negative sense of information are attributable to those who do not use information at their disposal. It therefore suggest that Weick’s sense making theory fit the study which is aimed at investigating causes of pregnancy related mortality as a result of non-use of antenatal information, a presupposition that at the end the case of General Hospital Kafanchan can provide answers of “what’s going wrong” with the use of antenatal information on healthcare of pregnant women.

4. Methodology

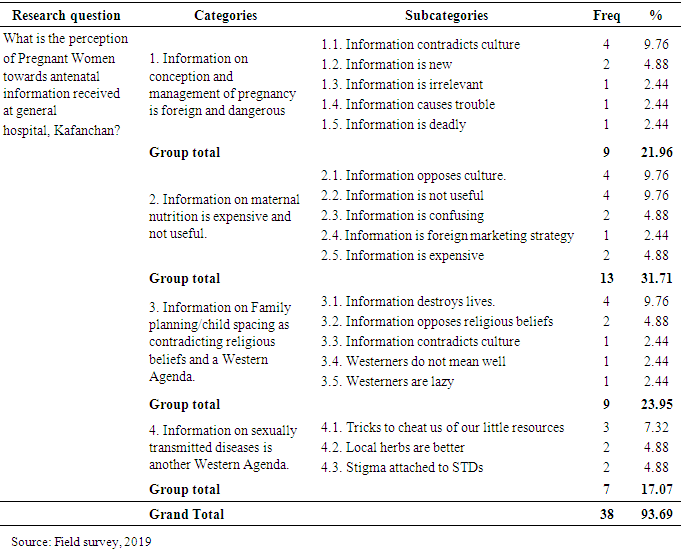

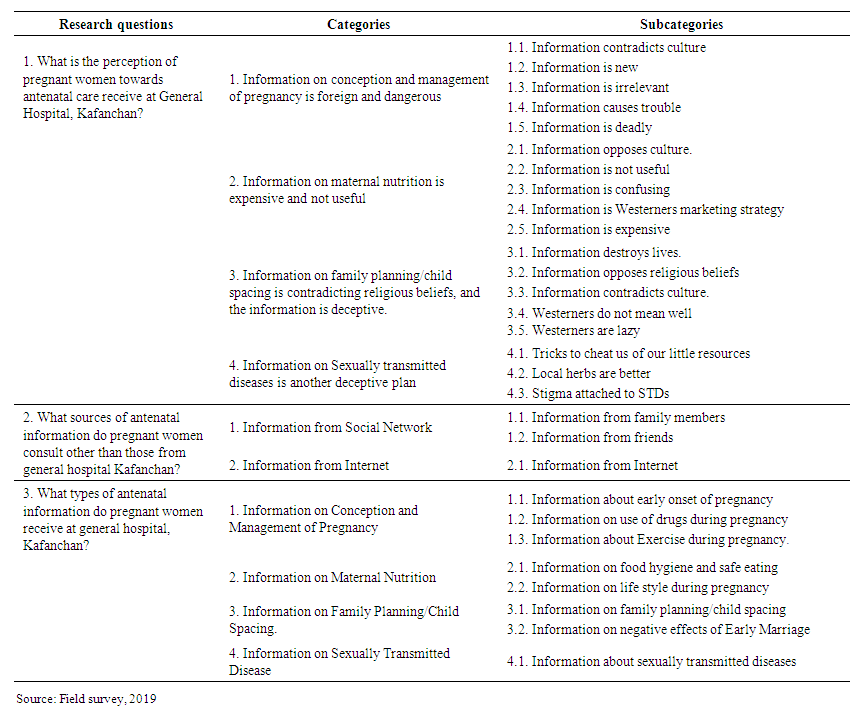

- The research leveraged on qualitative method to help it understand social life it intend to investigate and as a method facilitate the generation of words according to set objectives and providing answers to questions such as “how” or “why” of a phenomenon [29]. The qualitative research method was used to help the study explore the perception of pregnant women towards antenatal information within real-life content. However, phenomenography was adopted as the study research design to facilitate how pregnant women attending general hospital Kafanchan perceive, source and considered types of antenatal information for their healthcare. Phenomenography has been recommended by numerous authors based on its basic assumption that individuals based their understanding of a particular phenomenon on the meaning they attach to it, this meaning influence feelings and perception [30,31,32]. According to Reed [33], phenomenography describes the set of categories that shows the processes by which an individual conceive from various ideas. To pregnant women, the relevance of such information is to suggest ways to prevent mortality and improve live birth. Therefore, not to deviate from the study frame, the thrust of the research was guided by Weick’s Sense making theory using antenatal information as basis for the investigation.Participants’ selection for the study was based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria comprised that participant must be born female, must be pregnant, must be registered for antenatal care services at the general hospital Kafanchan, must have attended the monthly antenatal care clinics for at least four times in the last five months (at the time of data collection), and voluntarily consented to participate and share information on antenatal information given at the hospital and elsewhere. The exclusion criterion include, husbands who bring their wives for antenatal services, women who are not pregnant and those who are pregnant and attend antenatal care services but are not registered at the general hospital Kafanchan.A total of fifteen (15) pregnant women were purposively selected using a data redundancy/ saturation technique to elicit data. This technique are commonly used in qualitative researches to attain points that additional data collection contributes little or nothing new to the study [34]. Purposive sampling was considered appropriate for the selection of sample because only samples that could provide consistent information were needed, and it was 15 that fell within the size estimates proposed for grounded theory/ phenomenology/ case study [35]. Due to the research goal, the study adopted semi-structured interview and non-participant observation as instrument for data collection. Using interview guide, it facilitate the research to cover all research questions/objectives raised for the study.The semi-structured interview inquired around the set of predetermined open-ended questions, in addition to other questions that emerged from dialogue between the researcher and the participant. The semi-structured interview helped the study explore and utilise interpretative paradigms that encouraged participants to be at liberty to provide detailed scenario accounts and explanation of their opinion, and experiences [36]. The non-participant observation was used to observe the antenatal sessions, the dissemination of antenatal information and the behaviour of pregnant women towards the sessions.Data collection commenced after securing an introductory letter from the Department of Library and Information Science and ethical clearance from the Honourable Commissioner, Ministry of Health, Kaduna State. This was granted after ensuring that the study has no conflict of interest and guarantee that data collected is strictly for academic purposes and participant consented and assured of anonymity. Data collected were analysed using the qualitative content analysis strategy. The technique process are subjective interpretative of content of the textual data using systematic classification process of coding and identification of themes and patterns inherent in the data collected.Data analysis was based on valid inference and interpretation following a process that condenses raw data into categories [37]. The data collected in narrative forms were recorded using a digital recorder; the audio narratives were later transcribed, and examined for consistency with the research questions. These narratives were organised into related categories as described by Meriam [38] for analytic inductive process. A total of 197 open codes emerged from the narratives of participants (Table 1). Out of the 197 open codes, sixty one open codes related to perception of pregnant women, these six-one open codes were collapsed into eighteen subcategories which were further collapsed into four categories.Meanwhile, of the 197 open codes narratives on sources of antenatal information, 15 open codes emerged which were collapsed into three related subcategories, these three related subcategories were then collapsed into two categories. And finally, forty one open codes emerged from the narratives of participants related to types of antenatal information. The forty one open codes were collapsed into eight related subcategories that were further collapsed into four categories (Table 1).

| Table 1. Emergent categories and their subcategories from content analysis of collected data |

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Perception of Pregnant Women Towards Antenatal Information Received at General Hospital, Kafanchan

- This study sought to determine the perception of pregnant women about the antenatal information they receive at general hospital Kafanchan. Four categories emerged from the narratives of the participants of this study namely; (1) Information on conception and management of pregnancy is foreign and dangerous (2) Information on maternal nutrition is expensive and not useful (3) Information on family planning/child spacing contradicts religious beliefs, and the information is deceptive (4) information on sexually transmitted diseases is another deceptive plan (Table 2).

|

5.1.1. Information on Conception and Management of Pregnancy is Foreign and Dangerous

- Information on conception and management of pregnancy is foreign and dangerous category (9/61:21.96%) describes the narratives related to how pregnant women make sense of information they receive about conception and management of pregnancy at General Hospital, Kafanchan. Table 2 indicated that this category consists of five sub categories namely; Information contradicts culture (4/61:9.76%) Information is new (2/61:4.88%) Information is irrelevant (1/61:2.44%) Information causes trouble (1/61:2.44%)) Information is deadly (1/61:2.44%). These are explained below5.1.1.1. Information on conception and management of pregnancy contradicts culture: Information contradicts culture subcategory gives explanations on the perception of pregnant women about information on pregnancy test/examination they received at General Hospital, Kafanchan. “Participant 5 commented that,“These advices I get from the clinic contradict my culture. How can I naked myself and allow some body that I don’t know to examine me. No it is a taboo. I cannot abandon my culture. I am supposed to hide my pregnancy so that people will not know that I am pregnant. That is our tradition especially the first and second pregnancy”.5.1.1.2. Information on conception and management of pregnancy is new: This sub-category also emerged from the narratives related to how pregnant women make sense of information related to medication and morning sickness at general hospital, Kafanchan. “As for me, this information that I should not take any medicine when I know that I am sick is new to me”. In the same vein participant 2 said, “In the clinic when I complain about morning sickness and other related pregnancy issues, they tell me it is natural/normal and that I just have to endure until it stops. These are new advices that we don’t know their source”.5.1.1.3. Information on conception and management of pregnancy is irrelevant: This sub-category emerged as one of the ways pregnant women perceive information about headache at general hospital, Kafanchan. The participants’ perception on information about headache during pregnancy is that the information is irrelevant. Participant 1 stated that, “See these people (nurses) they keep telling us things that are not relevant, if I have headache and I complain to them, they always tell me that it is normal and it is because of the pregnancy that I should go and rest and have a good sleep that it would be over”.5.1.1.4. Information on conception and management of pregnancy causes trouble: This sub category is observed from the following narrative by participant 1 thus, “They explain that this advice about nausea is normal that we should not take anything causes trouble between me and my husband”.5.1.1.5. Information on conception and management of pregnancy is deadly: This sub-category also emerged from the narratives of a participant of this study. Participant 11 stated that,“This advice is deadly. Yes, you know how painful heartburn can be. These people (nurses) will say yes it is natural, don’t take anything even when they know that you cannot eat anything when you have the heart burn they will still insist that it will resolve itself. I think the information is meant to kill us. There is confusion among them so is it better to stick to our culture”.

5.1.2. Information on Maternal Nutrition is Expensive and Not Useful

- Information on maternal nutrition as expensive and not useful category (13/61:31.71%) includes narratives related to the understanding of pregnant women on information about maternal nutrition at general hospital, Kafanchan. Table 2 revealed that this category is made up of five sub categories namely; Information opposes culture (4/61:9.76%) Information is not useful (4/61:9.76%) Information is confusing 2/61:4.88%) Information is marketing strategy (1/61:2.44%) Information is expensive (2/61:4.88%) These subcategories are explained below:5.1.2.1. Information on maternal nutrition opposes culture: -This sub category is observed from the following narratives by participant 1,“The advices on maternal nutrition contradict with my culture. When I am pregnant I am not allowed to eat eggs because if I deliver my child will be stealing chickens. What my family members’ advise me not to eat, these people (medical practitioners) will say we should eat them. Again, anything that is sweet I am advised not to take it because it will make me have prolong labour during child birth. Yes is a taboo”.Participant 10 puts it this way, “There are many foods they advise me to eat but they are contrary to my culture. Most especially eggs. I don’t even want to touch eggs not to talk of eating it. This is because I don’t want to give birth to a thief”.Participant 14 said, “They are only deceiving us to forget our culture. I will never eat eggs when I am pregnant it is a taboo”. Participant 8 narrated that, “I am banned from taking sweets things. Like sugarcane, I don’t take it once I am pregnant and even after delivery. This is because these sweets things will make me have prolonged labour and my child after delivery will be having diarrhea always”.5.1.2.2. Information on maternal nutrition is not useful: This sub category is explained by Participant 3:“They say I need to eat this and that all in one stomach that is a problem already. Yes I see it as just mere talk because they don’t do what they advise us to do”. Participant 4 narrated that:“This advice is useless; because what they are teaching us to eat I don’t even know them. This is because they called the names of those things in English which I don’t know”. “I think the manufacturers connive with the medical practitioners to deceive us so that we can patronize their products. This is because they give us list of what to eat to remain healthy. Some of these foods end up causing more harm than good. I don’t follow their advice. I eat what I have and I am strong and healthy I think the information is not relevant”.Participant 2 puts it this way,“…My mother told me that I have to be careful with all these advices from the clinic. She said some of the foods they advise us to eat can affect us in the near future. She also said they are just deceiving us. I feed on natural foods”.Participant 1 summed it up, “Some of the foods they advise us to eat contradict my culture. Like eggs, sugarcane and many more. If my mother in-law sees me with eggs or sugarcane there will be trouble. Yes for example she said taking sweet drinks will make me have prolong labour, and eating eggs during pregnancy will make me deliver a child that will be stealing chickens so I eat what is approved by my culture’”.5.1.2.3. Information on maternal nutrition is confusing: This subcategory depicts narrative on the perception of pregnant women on information about maternal nutrition at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 2 stated that,“Most of the food they advise us to eat can create health challenges. For example, this week they will say eat this and that for your health, next week another person will say if you eat this you will have problem. Is like they are confused, so I prefer the advice from my experienced mothers”.Participant 6 says, “Too much advice is just stories. They are confusing us”.5.1.2.4. Information on maternal nutrition is a Foreign Marketing strategy: This shows the narratives on the perception of pregnant women on information about maternal nutrition at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 2 noted that, “My mother in-law said nobody advises her on what to eat and that she gave birth to healthy children and her too she is healthy even at her age. With this I see this advice as a strategy to dump foreign products for marketing in developing countries”.Participant 11 narrated that, “This directive that we at this or that every day is nothing but a plan to market the Westerners products in our country. What we have in terms of food is much better than what they are advising us to eat”.5.1.2.5. Information on maternal nutrition is expensive: Information is expensive subcategory includes narratives related to the non-use of information on maternal nutrition provided to pregnant women at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 1 commented that, “I have never changed my diet what I eat when I am not pregnant is what I eat when I am pregnant. Because I don’t have the money”. In the same vein participant 14 stated that, “I don’t know the names of the foods not to talk of the money to buy these foods. They think everybody is educated and working, everything is in English”.

5.1.3. Information on Family Planning/Child Spacing is Contradicting Religious Beliefs and the Information is Another Western Agenda

- Information on family planning/child spacing is contradicting religious beliefs and is deceptive Category (11/61:26.83%) includes narratives related to the perception of pregnant women about information on family planning/child spacing they receive at the general hospital, Kafanchan. From table 2 it can be seen that this category consists of five sub categories namely; Information destroys lives (4/61:9.76%) Information opposes religious doctrines (2/61:4.88%) Information contradicts culture (1/61:2.44%) Information causes unpleasant consequences (2/61:4.88%) Westerners don’t mean well (1/61:2.44%) and Westerners are lazy (1/61:2.44%) The individual subcategories are explained below:5.1.3.1. Information on family planning/child spacing destroys lives: This subcategory emerged from narratives related to non-use of information about family planning/child spacing by pregnant women at general hospital Kafanchan. Participant 1 stated that, “Family planning destroys lives and create unnecessary ill health for the women”. In the same manner, participant 7 said, “Family planning is meant to destroy lives and inflict ill health on us.”5.1.3.2. Information on family planning/child spacing opposes religious doctrines: This sub-category emerged from the narratives of participants of this study. Participant 1 said, “My religion does not support any family planning. I see this information as an attempt to oppose the doctrine of my religion”. In a similar way, Participant 4 stated that, “According to my mother in-law there was nothing like advice on family planning and they live longer and in good health than us. For me, this is true because God determines our health and how long we will live”.5.1.3.3. Information on family planning/child spacing contradicts culture: This sub category is explained by participant 2, “In my culture, it is expected that a woman should have a certain number of children within a given time. Failure to attain to that, the community will see her as someone who has issues with fertility”.5.1.3.4. Information on family planning/child spacing implies Westerners don’t mean well: This sub-category emerged as one of the ways pregnant women perceive information related to family planning/child spacing at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 1 stated that, “It is a plan to reduce our population and inflict poverty. Children are a gift from God who are you to control God’s plan. See these people (Westerners) they don’t mean well for us”. Participant 3 reported that,“My view about this advice on family planning in fact is contrary to their objectives. The white man (Westerners) is trying to play God in our lives by dictating to us how many children to have and when to have them. Yes, they are only trying to control our population. After all, it is God who gives children and know when to give without advice on family planning”.5.1.3.5. Information on family planning/child spacing implies Westerners are lazy: This sub-category also emerged as one of the ways pregnant women perceive information related to family planning/child spacing at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 5 remarked that, “These are just stories from westerners because they are lazy they cannot farm so they don’t have food to feed many children. That is why they are doing family planning”.

5.1.4. Information on Sexually Transmitted Diseases is Another Western Agenda

- Information on Sexually transmitted diseases is another Western Agenda Category (7/61:17.07%) describes the narratives related to how pregnant women make sense of information on sexually transmitted diseases at general hospital, Kafanchan. Table 2 revealed that this category consists of three sub categories namely; Tricks to cheat us of our little resources (3/61:7.32%) Local herbs are better 2/61:4.88%) Stigma attached to sexually transmitted diseases (2/61:4.88%) These subcategories are explained below:5.1.4.1. Information on Sexually transmitted diseases are just tricks to cheat us of our little resources: This subcategory explains narrative concerning the perception of pregnant women on information about sexually transmitted diseases at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 2 said, “I see it as a trick to cheat us of our little resources because the cost of treating STDs is high”. Participant 5 noted that,“They only concentrate on us, what about our husbands? If I am cured, and my husband is still having the disease, then I am still at a risk of acquiring the disease. So I think they don’t have remedy for these diseases rather itis just an exploitation of our money”.Participant 3 narrated that,“They (nurses) just want to know our status and collect our money by all means. They always advise us to go for different types of tests and is costing us so much that one will expect a healing but nothing has changed. They are only deceiving us and collecting our money”.5.1.4.2. Local herbs are better than Information on Sexually transmitted diseases: This subcategory explains narratives concerning the perception of pregnant women on information about sexually transmitted diseases at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 14 puts it this way, “I know that they (medical personnel) don’t have much knowledge of these diseases (STDs). The traditional medicine providers give us detail information and the remedy to this STDs. I think the herbal medicine is better than all these stories that have no end and no remedy”.Participant 1 summed it up, “They (hawkers) provide information on how fast and effective it is in curing STDs both for men and women. I prefer locally made herbs because they are 100% natural and have a proven track record of being effective and safe as described by the hawkers5.1.4.3. Stigma attached to STDs makes us not to use Information on Sexually transmitted diseases: This subcategory describes the narratives related to perception of pregnant women on information about sexually transmitted diseases at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 2 narrated that, “Because of the stigma attached to STDs I prefer to get advice and be treated locally”. Participant 4 reported that,“The stigma attached to sexually transmitted diseases in the society makes me not to open up and discuss the issue of STDs. We have neighbours with some of them, there is that tendency if they know one’s status they will disclose it to the community and people will just be avoiding me”.Participant 13 summed it up, “Ah! just to know my status and nothing more. When they know my status take it that everybody in the community will get to know about my status. You know the stigma attached to STDs can even kill more that the diseases itself”.

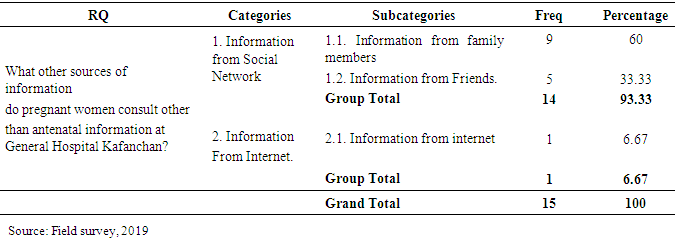

5.1.5. Sources of Antenatal Information

- This objective of the study sought to identify other sources of information consulted by pregnant women at general hospital, Kafanchan. To respond to this research question, the following sub question was asked: Share with me your other sources of information other than information from the antenatal clinic. Two categories emerged in response to the question namely; (1) Information from Social Networks and (2) Information from Internet (Table 3).

|

5.1.6. Information from Social Network

- Information from Social network category (14/15:93.33%) emerged from narratives of participants related to other sources they consult apart from the general hospital, Kafanchan. It could be seen from table 4 that this category has two subcategories namely; Information from family Members (9/15:60%) Information from friends (5/15:53.33) the subcategories are explained below: 5.1.6.1. Information from family members: This subcategory explains narrative concerning who the family members are and types of information they received from them. Family here comprised of the husband, mother, mother-in-law and parents. The narratives show that these sources of information were consulted in relation to family planning, complications or other issues related to the pregnancy and getting pregnant by women. Participant 2 stated that, “she got advice from her mother in-law who told her not to take pills or any method of family planning given to her at the hospital because, when the need for her to conceive again would come she would not be able to. The respondent categorically said that she planned to adhere to this advice given by her mother in- law”.Similarly, participant 8 reported that, “At times I am weak i feel as to go to the hospital to see the doctor and get medicine, my mother in-law will tell me that it is not necessary. That I can use this or that herb and when I use it I get better”. Participant 5 summed it up, ‘I received advice from my husband. He (husband) told me before this pregnancy that, I should not take any medicine from the hospital that all are for family planning. He (husband) said he will not be releasing water (sperm) he will withdraw his thing (penis) so that I will not be pregnant. I am not enjoying it (sex) again”.Other similar responses obtained show that medicines (traditional herbs) were also offered and advocated for these women.5.1.6.2. Information from friends: This subcategory also highlights narratives on other sources of information consulted by pregnant women other than antenatal information at general hospital, Kafanchan. The analysis shows pregnant women seek for advice from friends. Participant 3 stated that,“My friend said her sister’s experience works for her. She said she delivers at home and save money for naming ceremony”. Also, participant 4 reported that, “My friend advised me to use the traditional medicine for spacing my children”. In the same manner participant 9 narrated that, “my friend advised me on what to eat and what to avoid, for example, taking sugar cane is a problem that sugar cane will prolong my labor and that i will be crying because of the pains I will pass through”.

5.2. Information from Internet

- Information from Internet Category (1/15:6.67%) also emerged from narratives of participants related to other sources of information consulted by pregnant women other than antenatal information at general hospital, Kafanchan. Table 3 indicated that this category has just one subcategory namely; Information from Internet (1/15:6.67) the explanation of the subcategory is given below:5.2.1. Information from Internet: This sub-category emerged as one of the other sources of information consulted by pregnant women other than antenatal information at general hospital, Kafanchan. Narratives show that respondents in this subcategory felt they got the best form of information from the internet. Participant 1 said, “I have not consulted anyone for information; in my culture you do not tell people that you are pregnant. If I have confusion or I want to know more, I just Google and check. Like what to eat”.

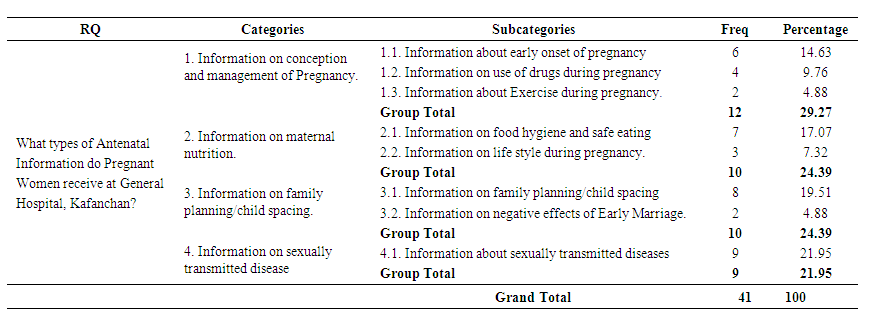

5.3. Types of Antenatal Information Pregnant Women Use to Improve Healthcare

- This research question sought to identify the use of information provided to pregnant women at general hospital, Kafanchan. To respond to this research question, the following sub research questions were asked: (1) Share with me how the use of information on conception and management of pregnancy has helped to improve your health. (2) Tell me how the use of information on maternal nutrition has helped to improve your health. (3) Share with me how the use of information on family planning/child spacing has helped to improve your health (4) Tell me how the use of information about sexually transmitted diseases has helped to improve your health. Four categories emerged from the narratives of the participants namely; (1) Do not improve their health because they do not utilize Information on Conception and management of pregnancy (2) Do not improve their health because they do not utilize Information on Maternal nutrition (3) Do not improve their health because they do not utilize Information on family planning/child spacing (4) Improves their health because they utilize Information on Sexually transmitted diseases.

5.4. Information on Conception and Management of Pregnancy

- Information about conception and management of pregnancy category (12/41: 29.27% describes the narratives related to the types of information pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. From table 4, it could be seen that this category consists of three sub categories namely; Information on early onset of pregnancy (6/41:14.63%) Information on use of drugs during pregnancy (4/41:9.76%) Information on exercise during pregnancy (2/41:4.88)

| Table 4. Types of information pregnant women receive at General Hospital, Kafanchan |

5.5. Information about Maternal Nutrition

- Information about maternal nutrition category (10/41:24.39%) gives explanations related to information on maternal nutrition pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. Table 4 revealed that this category consists of two sub categories namely; Information on food hygiene and safe eating (7/41:17.07) and Information on life style during pregnancy (3/41:7.32%)5.5.1 Information on food hygiene and safe eating: This subcategory depicts narratives on information related to food hygiene and safe eating pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 1responded that, “they even describe what we should be eating but, in small quantity. I cannot remember the types of food they advise us to eat”. Participant 2 noted that, “They said we should eat good food. They speak in English, I don’t know what they said we should eat”. In line with the above, Participant 3 stated that, “They advise us to eat good food. There are too many advices, so I cannot remember all”. Participant 6 summed it up, “They teach us things that we will eat that will build our body and also help the baby in our womb. They also advise us to wash our hands, fruits and vegetables. I don’t know the classes of food and fruits because they speak in English”.5.5.2 Information on life style during pregnancy: Information on life style during pregnancy sub category captures narratives related to information on lifestyle during pregnancy at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 1 narrated that, “They advised us that we should take care of our body, we should be bathing because some women, when they are pregnant, their armpits smell and you cannot sit close to them that we should look neat and we should look happy so that the baby will come out happy too. Also, we should keep our environment clean.”Participant 15 remarked that, “I received advice on personal hygiene. They taught us many things, they sometimes use English so me I don’t know what they said. Too many advices, I don’t know what they said”.

5.6. Information on Family Planning/Child Spacing

- Information on family planning/child spacing category (10/41:24.39%) describes the narratives related to information on family planning/child spacing pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. From table 4 it could be deduced that this category consists of two sub categories namely; Information on family planning/child spacing (8/41:19.51%) Information on negative effects of early marriage (2/41:4.88%)5.6.1. Information on family planning/child spacing: This subcategory emerged from the narratives related to information on family planning/child spacing pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 1 puts it this way, “They advised us that immediately we put to bed, and our children are six weeks, we should come to family planning/child spacing clinic, so that they will advise us on the type of contraceptives to use, in order to avoid giving birth to so many children that we cannot care for”.Participant 2 narrated that,“They advise us to come for family planning after six weeks of delivery. Secondly, they gave us advice that we should not deny our husbands sex, because some women will say I have just delivered, and complain that their back is paining them and other complains. They advise us to always give them (sex) so that they will not go outside the home and get infected which can be transferred to us, hence the need for early family planning”.In line with the above, participant 11 said,“They gave us advise about family planning, they stated that when you give birth, if you have a husband that cannot control himself and will not allow the delivery blood to flow out before he comes to you, you can come back after 1 month, 2weeks then they will give you the appropriate family planning injection”.5.6.2. Information on negative effects of early marriage: This subcategory contains narratives related to information on negative effects of early marriage pregnant women received at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 5 responded that, “They advised us about the risk of early marriage. Like this disease, Vesico-Vagina Fistula (VVF)”. Participant 1 also noted that, “They gave us detail information about the birth complication that arises from early marriage and its adverse health effect on young girls”.

5.7. Information about Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Information about sexually transmitted diseases category (9/41:21.95%) includes narratives related to types of information pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. Table 4 revealed that this category is made up of 1 subcategory namely; Information about sexually transmitted diseases (9/41:21.95%) This subcategory is explained below:5.7.1. Information about sexually transmitted diseases: This subcategory explains narrative concerning information on sexually transmitted diseases pregnant women receive at general hospital, Kafanchan. Participant 6 responded that, “They advise us that after giving birth we should come for test to know our status, and that of the infant especially with regards to HIV, Gonorrhoea and Hepatitis. Participant 8 summed it up, “They gave us advice on how to take care of ourselves in order to avoid any disease that will affect both mother and the baby. Like HIV/AIDS. In the issue of HIV/AIDS they advised us to use only new razor blade to cut our nails and to avoid multiple sex partners so that we can be healthy”.

6. Study Findings

- The perceptions of pregnant women on the types of information they receive at the general hospital, Kafanchan, include information on conception and management of pregnancy. They perceived it to be alien because it contradicts their culture and beliefs; thereby unsafe because many pregnant women have lost their lives using this information. Perception on maternal nutrition is expensive as it involves change of dietary habits. The information on family planning/child spacing is perceived to contradict religious tenants and perceived as a ploy to control population. Costs for running tests on STDs add financial burden and takes away financial resources are perceived by pregnant women attending general hospital, Kafanchan. This study revealed that Social Networks (Family and Friends) and the Internet are sources of information about pregnancy in general hospital, Kafanchan.The types of Information that pregnant women receive at the general hospital, Kafanchan, include: (a) information on conception and management of pregnancy, (b) information on family planning/child spacing, (c) information on sexually transmitted diseases and (d) information on maternal nutrition.

7. Conclusions

- The conclusion could be drawn from pregnant women attending general hospital, Kafanchan. As women whose perception of antenatal information they receive contradicts their culture and religion because the information is new and dangerous, the information is useless, the information is expensive and information is misleading. The informal sources of information dominate the information space in addition to those provided at the antenatal clinics at general hospital, Kafanchan. Eventually four types of antenatal information that makes the round among pregnant women at general hospital, Kafanchan include information on conception and management of pregnancy, information on family planning/child spacing, information on sexually transmitted diseases and information on maternal nutrition.

8. Recommendations

- Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations were proffered: 1. When there a balance of types of and sources of antenatal information, pregnant women are very liable to take advantages of using antenatal information which can change the negative perception towards antenatal healthcare services.2. Information should be broken into small packages in line with the types of information pregnant women receive and disseminate formally and informally. These could form discourse among pregnant women and the trained care givers (midwives, nurses and doctors) to know the impulse of the women while strategizing to educate and make them understand the implications the two types of information. 3. There is the need for designers of the antenatal programme to repackage the information from both the formal and informal sources so that women are not misled and could be made to understand that there is no ambiguity with the education provided by care givers, that is nurses, midwives and doctors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML