-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Library Science

p-ISSN: 2168-488X e-ISSN: 2168-4901

2019; 8(1): 18-25

doi:10.5923/j.library.20190801.03

Sources of Information on Reproductive Health among Teenage Girls in Kaptembwo, Nakuru County, Kenya

Janet Chepkoech1, Marie Khanyanji Khayesi1, James Onyango Ogola2

1Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Egerton University, Kenya

2Department of Literary and Communication Studies, Laikipia University, Kenya

Correspondence to: Janet Chepkoech, Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Egerton University, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

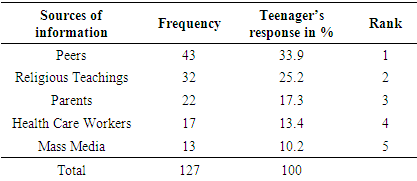

The study aimed at establishing the sources of information on reproductive health among teenage girls in Kaptembwo, Nakuru County, Kenya. Data was collected from a sample of 127 teenage girls aged between 13-19. Purposive sampling technique was used. The results obtained from Kaptembwo showed that, five (5) different sources were identified as the ones that provide the teenagers in Kaptembwo with reproductive health information. Majority of the teenage girls reported that they received their information on reproductive health from their peers. The study concludes that sources have been found to be interacting with access and use of reproductive health information among teenage girls. Some information sources get more used than others depending on reliability in providing potential reproductive health information. The preferred source for information depends on the type of information to be delivered, the overriding principle being the source must be authoritative in that type of information.

Keywords: Reproductive Health Information, Teenage Girls, Access and Use of Reproductive Health Information

Cite this paper: Janet Chepkoech, Marie Khanyanji Khayesi, James Onyango Ogola, Sources of Information on Reproductive Health among Teenage Girls in Kaptembwo, Nakuru County, Kenya, International Journal of Library Science, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 18-25. doi: 10.5923/j.library.20190801.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Reproductive health (RH) is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being (not merely the absence of reproductive disease and infirmity) in all matters relating to reproductive system, its functions and processes. Such matters relating to reproductive health include promotion of responsible and healthy reproductive behaviour, management and prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STI) including HIV/AIDS, having safe sexual experiences, which are free from discrimination and management of complications that may arise due to abortion (World Health Organization, 2011). Sexual and reproductive health is made of family planning, antenatal care, safe delivery and post natal care, prevention and treatment of infertility, prevention of abortion and management of consequences of abortion, treatment of reproductive tract infection, prevention, care and treatment of STIs including HIV/AIDs and information, education and counselling (World Health Organisation, 2004).A teenager, or teen, is a person who falls within the ages of thirteen-nineteen (13-19) years old. During this age, teenagers develop biologically and psychologically as they move towards independence. This period is associated with risk taking and experimental behaviour, which makes teenage girls exposed to sexual and reproductive health complications (WHO, 2004). Meena, Anjana, Jugal, & Gopal, (2011) stated that early child-bearing remains to be an obstacle to developments in the enlightening, economic and social status of women in all parts of the world. Early parenthood can severely limit learning and employment chances. This impact on the quality of teenagers’ lives and the lives of their children. It can therefore be clearly seen that reproductive health information is a very important factor in the lives of teenage girls. Meena et al. (2011) further explains that, good reproductive health should include freedom from risk of sexually transmitted diseases, the right to regulate one’s own fertility with full knowledge of contraceptive choices and the ability to control sexuality without discrimination because of age, marital status, income or similar considerations.Globally, there are existing barriers in accessing reproductive health information. They include poor access, availability and acceptability of the services, lack of clear directions and services, lack of privacy, appointment times that do not accommodate teenage girls’ little or no accommodation for walk-in patients, limited services and contraceptive supplies and options calling for referral (WHO, 2004). Adolescents globally feel embarrassed when seeking for information on reproductive health and are more likely to seek information and services after sexual exposure (Hocklong et al., 2003).The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) set the stage for putting teenagers’ sexual and reproductive health (SRH) on the international agenda. During the conference, it was realised that existing health, education and other social programmes had largely ignored reproductive health needs of young people (MOH, 2005). The conference adopted a plan of action which formed the basis for programmes addressing the SRH needs of adolescents globally. The five-year progress review of this plan (ICPD +5) made a further call for countries to ensure that adolescents have access to user friendly services that effectively address their sexuality, education and counselling and health promotion activities while encouraging their active participation (WHO, 2004). Information on reproductive health needs to be made available to teenage girls to help them to understand their sexuality and protect them from unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. Teenage girls have a right to access all the reproductive health services without any discrimination in the society.The ICPD further highlighted the vulnerabilities of adolescents and called for greater recognition of teenagers as a special category with special needs. It emphasised the need to provide adolescents with reproductive health information. Additionally, the ICPD raised the need to remove social barriers that hinder adolescents in accessing reproductive health services (Germain, 2000). ICPD suggested that teenage sexual and reproductive health issues are addressed through the elevation of accountable and healthy reproductive and sexual behaviour, including voluntary abstinence and the establishment of suitable services and counselling precisely suitable for that age group (WHO, 2004).According to a study done by Lukale (2015) on adolescent reproductive health concerns in Sub-Saharan Africa, teenagers have specific reproductive health vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities include high adolescent birth rate, kidnapping, destructive traditional practices (such as female genital mutilation), unwanted pregnancies, abortions and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). These young people need access to sexual and reproductive health information and services so that they can prevent unintended pregnancy and decide if and when to have children. Most teenagers engage in sexual activities because they lack support from their parents concerning reproductive health issues. Some teenagers may be forced to drop out of school because of unplanned pregnancies. Teenage girls are at high risk because they might also expose their children to malnutrition which may lead to death. Lukale (2015) identified specific reproductive health vulnerabilities faced by teenage girls but there is no clear picture if these vulnerabilities are caused by not accessing reproductive health information.In Kenya, adolescents face several reproductive health challenges. These include early pregnancy which is mostly unwanted, complications of unsafe abortions and complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Adolescents lack easy access to quality and friendly healthcare, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STI), safe abortion services, antenatal care and skilled attendance during delivery, which result in higher rates of maternal and perinatal mortality (Kenya National Commission on Human Rights ( KNCHR), 2012).Teenagers need to be engaged in all matters relating to sexual and reproductive health to help them gain information that will help them make informed decisions. The Ministry of Health has tried to help in providing a framework for equitable, efficient and effective delivery of quality reproductive health services to all teenagers. Many teenagers can still not access this information due to some factors. However, this study comes in to fill the gap by looking at socio-economic factors, sources of reproductive health and approaches as determinants of access and use of reproductive health information among teenage girls.The youths in Nakuru County, like their counterparts in Kenya, have a range of issues and challenges related to reproductive health, mainly teenage pregnancies, abortions, school dropout, drug and substance abuse and sexual violence Kenya Service Provision Assessment (KSPA) (2010). In Nakuru County, other than the government of Kenya, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have also put a lot of effort to increase access and use of reproductive health services among young people through various initiatives. For example, Family Health Options of Kenya (FHOK) has started various Youth Friendly Reproductive Health Services (YFRHS).The persistence of reproductive health related problems among adolescents globally, and regionally that has been revealed from the literature also apply to Nakuru, Kenya.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sources of Information on Reproductive Health

- Information source can be physical or digital entities in a variety of media providing potential information. An information source contains relevant information whereas channel guides the user to pertinent sources of information. For the purpose of this study, sources of information on reproductive health included parents, religion and culture, peers, mass media and health care workers.

2.1.1. Parents

- Parents and members of the family are significant sources of knowledge, beliefs and attitudes for teenage girls. They are role models who shape young people’s perceptions and influence the choices that teenagers make about their sexual behaviour (Li, Shah & Zhang, 2007). Youth-serving agencies and medical professionals recognised the important role that parents play in the lives of teenagers. However, many believe that confidential access to sexual health services is essential for teenagers who are or are about to become sexually active. Some teenagers might avoid seeking reproductive health information and STI services if they are forced by healthcare workers to involve their parents. In Boonstra and Jones’ (2004) study, teenagers may avoid seeking advice from their parents and this will hinder them from accessing relevant information on reproductive health. According to Boostra and Jones (2004), parents are significant sources of reproductive health. However, little is known whether parents feel comfortable in discussing reproductive health information with their teenage girls. Besides, parents may also lack adequate information or are incorrectly informed.This study agreed with Kamrani, Sharifa, Hamzah & Ahmad (2011) observations that sources of sexual and reproductive health information are categorised into six levels: the first level source of information are mothers, second level are siblings, third level are fathers, fourth level are friends, fifth level are teachers and sixth level are books/ internet. Because of cultural beliefs, teenage girls are not supposed to talk anything about sexual and reproductive information with their parents, but they prefer discussions with their friends. Therefore, friends could increase accessibility on reproductive health information, but other factors could be a barrier like socio-economic factors and the effectiveness of the approaches used.Generally, parents have authority to make health decisions on behalf of their teenagers, grounded on the principles that young people lack the maturity and decision to make fully knowledgeable decisions before they mature. Parents are the most trusted entities in the lives of teenagers (Li, Shah & Zhang, 2007). Based on research done in Ethiopia on Adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues among high school students, it was found that parents need to be close to their teenagers so that they can share any information concerning sexuality. Teenagers need guidance as they transition from childhood to adulthood and therefore parents need to be close to them to help them make the right decisions in their lives. Parents have significant potential to reduce sexual risks behaviour and promote healthy teenagers’ sexual evolution. Parents can realise this potential through communicating with their teenagers about sexual behaviour and decision-making (Ayalew, Mengistie, & Semahegn 2014). Parents need to be close to their teenagers so that they can help them solve the challenges arising in their day-to-day lives. Li, Shah and Zhang (2007) assert that parents are the most trusted people in the society to pass any information on reproductive health to their children. However, it is not clear whether the information on reproductive health given by parents is relevant, accurate and encompasses a narrow or wide range of reproductive health topics.

2.1.2. Religion and Culture

- Generally, teenagers feel that religion has no impact on their daily lives, and none say that they have gained any useful information about sexual and reproductive health at the church (Nobelius et al., 2010). The Catholic Church, however, appears to have a confounding role in the promotion of safer sex messages for example abstinence for all teenage girls is encouraged without allowing them to use condoms. Health care providers need to remain aware that teenagers and their parents may hold different religious beliefs. This can be particularly relevant for teenagers living in rural communities, where the health care provider may know the teenagers and their family and make assumptions about their religious or cultural beliefs (Dickens & Cook, 2005). Some communities have different beliefs and they prefer only parents to pass information on sexual and reproductive health. Some parents believe that a different person may mislead their teenagers. Religion discourages the use of family planning methods and this may increase the risk like unwanted pregnancies, school dropout and abortion among teenage girls.Margaret and Thomas (2005) in their work on religion, reproductive health and access to services states that American women believe that catholic religious teachings should not be allowed to impact the kind of services available in the community and clinical settings. Moreover, despite the efforts that engage religious leaders and heath care workers to promote reproductive health service, little is understood about their influence on teenage girls’ knowledge and attitude towards reproductive health information and services.A study done in South Africa on cultural clashes in reproductive health information in schools explains perceptions about reproductive health information among school teachers and learners in a rural area. Teachers are forced to wear a mask when it comes to educating youngsters about sexuality. Metaphorical language for genital organs and sexually related activities had hidden meanings in passing such messages to the entire group (Mbananga, 2004). Language is clearly crucial in the construction of sexual and reproductive health information. Accepted language should be used in the community. Education around HIV/AIDs epidemic and the provision of information on reproductive health are perceived as unethical issues among female teachers since it involved talking to children about sexual intercourse. Mbananga (2004) further argues that language is a barrier in communicating reproductive health information among teenage girls. Despite the sensitivity of reproductive health issues, there is increasing consensus and acknowledgement that it is important to institute effective sex education programmes to equip teenage girls with reproductive health information and skills to help them make informed decisions on reproductive health.

2.1.3. Peers

- The peer group is the only place where majority of teenagers feel they can openly discuss, and debate information gathered from other sources (Nobelius, 2010). Teenagers prefer sharing any information on sexual and reproductive health with their friends because they will learn from one another and make the right decision concerning their sexual health. Sex related matters among teenagers are discussed mostly with age-mates because they trust them, and they may lack confidentiality among other people especially parents (Kennedy, Bulu, Harris, Humphreys, & Malverus, 2014). Teenagers who are 13 years may have limited knowledge on sexual and reproductive health as compared to 19 years old. Therefore, they will share information with other teenagers to help them prevent adverse consequences of sexual activity.A study done by Senderowitz (2003) on rapid assessment of reproductive health services concluded that youths do not seek care due to national laws and policies restricting care based on age and/or marital status, poor understanding of their changing bodies and insufficient awareness of risks associated with STIs, including HIV/AIDs and early pregnancy. Kennedy et al. (2014) posit that age is a factor that hinders teenage girls from accessing reproductive health information. In other studies, peers were principal sources of reproductive health information. However, little is known about the judgment of teenage girls concerning reliability of their sources of reproductive health.

2.1.4. Mass Media

- Kibombo, Musisi and Neema (2014), reveals that mass media such as press, magazines, radio and television broadcast are among the factors that influence access to information on sexual and reproductive health. There are a number of programmes targeting teenagers that are aired on radio and television related to teenagers’ sexual and reproductive health. Teenagers find it easy to access sexual and reproductive health information through mass media like listening to some programmes about sexual and reproductive health on radio and also watching some selected television programmes that educate them on sexual and reproductive health. Teachers and parents provide information mainly on topics with less cultural taboos, such as knowledge about puberty because they are the most trusted entities (Li, Shah & Zhang, 2007). Teenagers find it easier watching some programmes in the absence of their parents and this helps them to discuss with their friends. Magazines are favourite and most young people, especially teenagers, read more on sexual behaviour, which may influence them. Previous studies have indicated that media were the principal sources of reproductive health information. However, little is known about the views of teenage girls concerning credibility of their sources of reproductive health information.

2.1.5. Health Care Workers

- The literature showed that health care providers have found that adolescents do not seek health care because of the following reasons: concern about confidentiality, lack of trust in healthcare providers, embarrassment, lack of awareness and knowledge of services and lack of knowing how to access services (Jarret, Dadich, Robards, & Bennett, 2011). Health care workers need to be knowledgeable, non-judgmental and confidential. They should allow adequate time for consultation on issues regarding information for sexual and reproductive health. It is for local authorities, working with health and other associates, to carry on taking the lead in the reduction of teenage pregnancies (Goicolea, 2010). Health care workers need to be close to teenagers and share any information concerning sexuality. Some teenage girls may be free in discussing sexual matters with their health care workers than their parents. Despite the effort that engages health care workers in promoting reproductive health information, little is understood about the quality and accuracy of teenage girls’ knowledge, attitudes and preference of health service providers for reproductive health.

3. Statement of the Problem

- Kaptembwo ward is one of the largest informal settlement areas located to the west of Nakuru County. It is characterised by high level of unemployment, insecurity, early child bearing, early marriages, sexual violence and high level of alcoholism. Further, socio-economic status of teenage girls in Kaptembwo mirrors lack of knowledge and information about reproductive health matters relating to their bodies. Consequently, they depend on their peers for information. These highlight a dire need of reproductive health information and services for teenage girls. The high level of poverty in Kaptembwo ward limits access to basic facilities including health care facilities.The Government of Kenya, through the Ministry of Health and other relevant stakeholders, have tried to enhance the reproductive health status of all Kenyans especially to the vulnerable groups like teenage girls through policies, legislations and targeted interventions to enhance equitable access, quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of reproductive health services. Despite this initiative, there is still an increase in early pregnancy, abortion, STIs including HIV/AIDs, school dropouts, poor performance, psychological trauma, single parenting and gender-based violence among teenage girls. This study, therefore, aimed to establish the Sources of Information on Reproductive Health among Teenage Girls in Kaptembwo, Nakuru County, Kenya.

4. Methodology

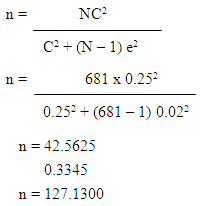

- The study employed descriptive survey design that involves interviewing and administering questionnaires to a sample of teenage girls from Kaptembwo primary school, Nakuru West secondary school and Youth for Christ Group Nakuru. The target population in the study comprised all teenage girls who were aged between 13-19 years in and out of school in Kaptembwo, Nakuru Kenya. The accessible population comprised of selected teenage girls from the ages 13-19 years from Nakuru West Secondary School (408 teenage girls), Kaptembwo Primary School (183 teenage girls) according to the school register, (2016) and Youth for Christ Group Nakuru (90 teenage girls) making a total of 681 teenage girls.Study Design: The study employed descriptive survey designStudy Location: The study was conducted in Kaptembwo, Nakuru Kenya.Study Duration: March 2017 to March 2018.Sample size: 127 teenage girlsSample size calculation: From a study population of 681, a sample size was drawn using Nassiuma’s (2000) formulae:

Thus, the sample size is 127 samplesWhere: n = Sample size,N = Population,C = Coefficient of variation,e = Standard error.C = 25% is acceptable according to Nassiuma (2000), e = 0.02 and N = 681Subjects & selection method: From the selected schools, the researcher used simple random sampling technique to select 76 teenage girls in Nakuru West secondary school, 34 teenage girls in Kaptembwo primary school (upper primary class 6-8). To select teenage girls who were out of school, the researcher purposively selected Youth for Christ group Nakuru which is a youth group formed to represent teenage girls who were out of school. The researcher used simple random sampling to select 17 teenage girls in the group.Inclusion criteria:1. Teenage girls2. Ages 13 to 19 yearsExclusion criteria:1. Teenage boys2. Teenage girls less than 13 years and teenage girls above 19 yearsProcedure methodology: The researcher sought an introductory letter from Egerton University Graduate School to assist in obtaining a research permit from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation before starting the research process. The researcher visited the County Commissioner’s Office and the County Director of Education to inform them of the intention to collect data. The researcher proceeded to the two schools and the youth group to obtain consent from the heads and the area chief. Questionnaires were then taken to the teenage girls in their classes. The questionnaire was also taken to the youth group at their meeting place and it was researcher administered. The researcher herself distributed the questionnaires to the teenage girls who were purposively selected and waited for the respondents to complete and go back with the complete questionnaires. This helped the researcher to avoid loss of questionnaires and the researcher was able to clarify some questions to the respondents. The researcher assisted in reading the questions because some teenage girls in the group had challenges in understanding the questions. After concluding quantitative data collected through the questionnaire, the researcher embarked on interviewing the key informants (heads from each school who were one female teacher and one male teacher as well as head of the youth group and health care worker in Rhonda Health Centre). The purpose of the interview was to get more in-depth information that was used to explain in a detailed manner, the results found from quantitative phase. The researcher met the respondents (3 heads and the health care worker) and clearly explained the purpose of carrying out the research. The researcher interacted well with the respondents and recorded all the responses while ensuring that the most important points were noted. After the entire interview questions were answered, a complete interview schedule was then organised in readiness for analysis and interpretation.Statistical analysis: Both qualitative and quantitative techniques were used in data analysis. Quantitative data obtained through the questionnaires were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 software. The data was then presented using descriptive statistics of mean scores, frequency tables and percentages. The influence was tested using Regression Coefficient. For qualitative data, data was analysed using narrative statements based on relevant themes.

Thus, the sample size is 127 samplesWhere: n = Sample size,N = Population,C = Coefficient of variation,e = Standard error.C = 25% is acceptable according to Nassiuma (2000), e = 0.02 and N = 681Subjects & selection method: From the selected schools, the researcher used simple random sampling technique to select 76 teenage girls in Nakuru West secondary school, 34 teenage girls in Kaptembwo primary school (upper primary class 6-8). To select teenage girls who were out of school, the researcher purposively selected Youth for Christ group Nakuru which is a youth group formed to represent teenage girls who were out of school. The researcher used simple random sampling to select 17 teenage girls in the group.Inclusion criteria:1. Teenage girls2. Ages 13 to 19 yearsExclusion criteria:1. Teenage boys2. Teenage girls less than 13 years and teenage girls above 19 yearsProcedure methodology: The researcher sought an introductory letter from Egerton University Graduate School to assist in obtaining a research permit from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation before starting the research process. The researcher visited the County Commissioner’s Office and the County Director of Education to inform them of the intention to collect data. The researcher proceeded to the two schools and the youth group to obtain consent from the heads and the area chief. Questionnaires were then taken to the teenage girls in their classes. The questionnaire was also taken to the youth group at their meeting place and it was researcher administered. The researcher herself distributed the questionnaires to the teenage girls who were purposively selected and waited for the respondents to complete and go back with the complete questionnaires. This helped the researcher to avoid loss of questionnaires and the researcher was able to clarify some questions to the respondents. The researcher assisted in reading the questions because some teenage girls in the group had challenges in understanding the questions. After concluding quantitative data collected through the questionnaire, the researcher embarked on interviewing the key informants (heads from each school who were one female teacher and one male teacher as well as head of the youth group and health care worker in Rhonda Health Centre). The purpose of the interview was to get more in-depth information that was used to explain in a detailed manner, the results found from quantitative phase. The researcher met the respondents (3 heads and the health care worker) and clearly explained the purpose of carrying out the research. The researcher interacted well with the respondents and recorded all the responses while ensuring that the most important points were noted. After the entire interview questions were answered, a complete interview schedule was then organised in readiness for analysis and interpretation.Statistical analysis: Both qualitative and quantitative techniques were used in data analysis. Quantitative data obtained through the questionnaires were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 software. The data was then presented using descriptive statistics of mean scores, frequency tables and percentages. The influence was tested using Regression Coefficient. For qualitative data, data was analysed using narrative statements based on relevant themes.5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Results

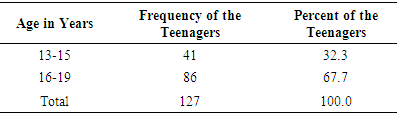

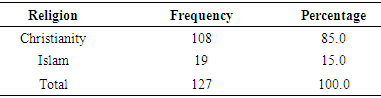

- Demographic Characteristics of the Teenage Girls in KaptembwoThree attributes of the teenage girls which were considered important to this study were age, education levels and religion. Age Distribution of the TeenagersThe frequency distribution of the respondents by age is shown in Table 5.1.

|

|

|

5.2. Discussion

- Peer as a source of reproductive health information was ranked the highest by the respondents with 33.9%. Nobelius et al. (2010) found that peer group is the only place where majority of teenagers feel they can openly discuss and debate information gathered from other sources sex related matters among teenagers are discussed mostly with age-mates because they trust them and they may lack confidentiality among other people especially parents.Religious teachings were the second source of reproductive health information by the respondents. This relate to Caldwell (2000) findings that religious teachings have a prominent place in people’s understanding of HIV/AIDS in Africa; and therefore may be an important source of reproductive health information. On the contrary, (Nobelius et al., 2010) noted that teenagers feel that religion has no impact on their daily lives, and none say that they have gained any useful information about sexual and reproductive health at the church.Parents were ranked as third source of reproductive health information. Teenagers need guidance from parents as they transition from childhood to adulthood. The results are consistent with Li, Shah & Zhang, 2007 who noted that parents have the legal authority to make health decisions on behalf of their teenagers, grounded on the principles that young people lack the maturity and decision to make fully knowledgeable decisions before they mature. Parents are the most trusted entities in the lives of teenagers. Ayalew et al., (2014) noted that parents need to be close to their teenagers so that they can share any information concerning sexuality.The health care workers were ranked fourth as a source of information. This low ranking may be attributed to various reasons such concerns of confidentiality. Jarrett et al., (2011) pointed out that adolescents do not seek health care information from health care providers because of concern about confidentiality, lack of trust in healthcare providers, embarrassment, lack of awareness and knowledge of services and lack of knowing how to access services. In addition, Goicolea (2010) noted that health care workers need to be knowledgeable, nonjudgmental, confidential, allows adequate time for consultation in issues regarding to information for sexual and reproductive health. It is for local authorities, working with health and other associates, to carry on taking the lead in the reduction of teenage pregnancies.Even though mass media techniques have the advantage of covering wider community members in sensitization of reproductive health issues, mass media was ranked the last source of information on reproductive health with 10.2%. This may be attributed to the fact that Kaptembwo is an informal settlement with majority of low income earners and unemployed. Majority may not own such media as radio, television, newspaper, magazines among others. Kibombo, Musisi and Neema (2014), reveal that mass media such as press, magazines, radio and television broadcast is among the factors that influence access to information on sexual and reproductive health. There are a number of programs targeting teenagers that are aired on radio and television related to teenagers’ sexual and reproductive health. Teenagers may find it confidential watching some programs in absence of their parents and this will help them to discuss with their friends. Magazines are favorite and most young generation especially teenagers read more on sexual behaviour, which may influence them.

6. Conclusions

- The study concludes that sources of information have been found to be interacting with access and use of reproductive health information among teenage girls. Teenage girls prefer sharing information on reproductive health among their friends (peers) because they have similar experiences.

7. Recommendations

- Parents should create a conducive environment that will enable the teenage girls to ask questions, express their thoughts and ideas and seek clarifications on sexual and reproductive health issues.There should be a consensus among teachers, religious leaders, parents, policy makers and all other stakeholders. The consensus should aim at promoting sex education in schools. Social media should be used as an alternative important communication channel for reaching teenage girls concerning all issues on sexual and reproductive health. This would include utilizing social networking and internet forums to disseminate sexual and reproductive health information. Most teenage girls prefer internet because it is confidential to them. Teenage girls can access reproductive health information through their mobile phones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I wish to express my gratitude to my supervisors Dr. Marie Khayesi and Prof. Onyango, James Ogola for their valuable assistance, guidance and suggestions during the period of formulating the research proposal, data collection and writing of the thesis report. I give special thanks to Dr. Mutinda, Kennedy Obumba Ogutu and James Mushori who offered needful peer critique and encouragement whenever these were required. I would like to acknowledge the Chief from Kaptembwo at the time of the study Mr. Koech for his time and also the teenage girls of Kaptembwo Primary School, Nakuru West Secondary School and Youth for Christ Group who participated by giving responses to my questionnaires. Above all, I thank the Almighty God for giving me good health and wisdom throughout my study period.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML