-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Mobile Studies

2019; 1(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.jms.20190101.01

Situation Analysis of Mobile Phone Theft in Zambia

Benaiah Akombwa1, Simon Tembo2

1Center for Information and Communication Technologies, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

2Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Benaiah Akombwa, Center for Information and Communication Technologies, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

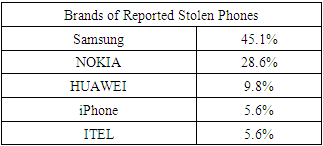

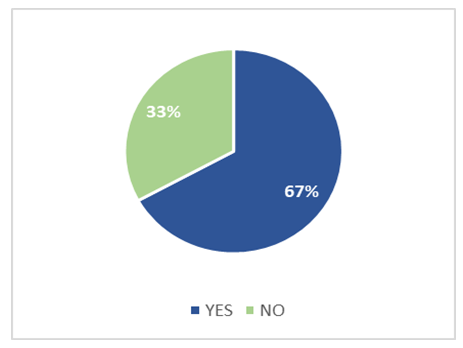

As in most nations in Africa, the problem of mobile or cell phone theft is something that local authorities in Zambia are desirous to address. With advances in technology, phones have gotten smaller and of high value. Motivated by this rising challenge, this study purposed to propose an appropriate framework that would help reduce phone thefts. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in which 420 structured questionnaires were distributed among Lusaka residents in four different districts using a multi-stage cluster sampling method. Interviews were also done with various stakeholders such as the Mobile Network Operators, ZICTA and the Police. Data was analysed descriptively using SPSS version 16. Results of the study revealed a 67% phone theft prevalence and confirmed that phone thefts in Zambia have been on the rise, without any seemingly workable remedy from the authorities to counter the issue. Further, Samsung mobile phones topped as the most frequently stolen followed by Nokia. Currently, victims of lost or stolen phones report the matter to the Police then the law enforcement wing tries to recover the phone through a manual process. This study proposed to develop a framework that would help enhance collaboration by interested parties and eventually reduce the prevalence of phone theft by ultimately blocking the handset and preventing its reuse in Zambia once reported stolen.

Keywords: Mobile Phone theft, CEIR Zambia, Addressing Cell Phone Theft in Zambia, IMEI Blacklisting in Zambia

Cite this paper: Benaiah Akombwa, Simon Tembo, Situation Analysis of Mobile Phone Theft in Zambia, Journal of Mobile Studies, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.jms.20190101.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There are well over 5 billion GSM users globally [1] and mobile phones, indubitably, are an integral part of day-to-day activities for a substantial populace of our planet. The era of Mobile Telecommunications in Zambia was preceded by the traditional fixed, manual phone exchange system commonly known as the public switched telephone network (PSTN), with the first phone exchange having been installed in Livingstone as far back as 1913 [2]. Till the introduction of multiparty democracy in the early 1990s, telecommunications service provision in Zambia was a monopoly of the Postal and Telecommunications Company (PTC) [2] [3]. To align with global telecom sector reforms, the government of the Republic of Zambia enacted the Telecommunications Act in 1994 to provide a legal framework that would open the market to new players. This liberalisation permitted entry of competitors in nearly all telecom aspects except for the international gateway (IGW) and the PSTN [3].There are presently three mobile network operators in Zambia [4]. The first mobile telecommunications company was licenced in 1994 when ZAMTEL was permitted to offer mobile cellular services to the general public [5]. Then followed the first privately-owned mobile operator to enter the Zambian market in 1995, Telecel Zambia, which is now MTN after a buyout in 2006 [5] [6]. Zamcell, later taken over by Celtel, then Zain, (currently Airtel) entered the market in 1997 as the third mobile network operator [6]. To date, ZAMTEL is still holding privileged monopoly on fixed-line or Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) services [5] [6]. The Zambian government took action to sell off seventy percent (70%) of ZAMTEL equity to Libya's LAP Green in quarter one (Q1) of 2010. This move, alongside the reduction of licence fees from the previous USD18 million to USD350 thousand, practically took away ZAMTEL's monopoly over the international gateway (IGW) and attracted new entrants. This resulted in significantly reduced international calling rates by as much as seventy percent (70%) [6]. The sale of ZAMTEL to LAP Green was later reversed after the Patriotic Front (PF) took over power from the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) in 2011.In a Press Statement issued on 19th March, 2018, the Zambian ICT Regulator (ZICTA) issued a notification of award of a licence to a fourth mobile network operator – UZI Zambia Limited [7]. Thus to the three existing mobile network operators (MNOs) Airtel, MTN and ZAMTEL is now added a company whose major shareholding entity is Unitel International Holding B.V registered in Netherlands. In a Press Release, the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC) - the advocate and regulator for Competition and Consumer welfare in Zambia - anticipates that the introduction of a fourth mobile network operator shall offer alternatives to customers as well as drive innovation envisaged to trigger growth of the sector [8].In the year 2010, Zambia had a mobile penetration rate of 41.6% [9]. As at end of Q1 of 2019, the country reached a mobile penetration rate of 90.3% [9], representing a growth of more than 100 percent. With the escalating advances in technology, cell phones have gotten smaller and of high value, making them an easy target of criminals [10] [11].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sub-Saharan Africa Mobile Economy

- According to a joint report published in 2012 by the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the African Union, Africa's GDP has been increasing by an average of 5%. A major causative aspect has been the uptake of information and communications technologies (ICTs) and, predominantly, the enormous increase in mobile communications [12]. Mobile phones don't just end at being communication gadgets; they are now the principal means by which life-improving services are accessed by users in Sub-Saharan Africa [13]. Cell phones are now at the core of financial inclusion for the poor and afford access to financial services cheaply [14]. With mobile technology being the most common tool for most consumers to get online, the mobile internet subscriber base has quadrupled since 2010. By end of 2017, 135 mobile services in 39 countries were active with 122 million active accounts in the region. Further, 444 million unique mobile subscribers with a penetration rate of 44% were recorded for 2017. GSMA Intelligence projects a 4.6% growth rate to 634 million subscribers by 2025 [13].The uptake of smartphones has grown rapidly in Sub-Saharan Africa, with 250 million smartphone connections recorded as at end of 2017 – translating to a penetration rate of 34%. The smartphone adoption rate is projected to grow to 67% by the year 2025 [15] [16].

2.2. Theft of Mobile Cell Phones

- The theft of mobile phones has been a growing concern globally. With advances in technology, cell phones have gotten smaller, portable and of high value – capable of carrying substantive amounts of user information. This has made mobile phones an easy target of criminals [17]. The GSM Association (GSMA) brings together approximately 800 operators and represents the interests of mobile operators worldwide with over 250 players in the mobile ecosystem, among which are included handset and equipment manufacturers and software companies. The GSM Association allots globally unique identifiers to device manufacturers. The unique identity is known as an International Mobile Equipment Identifier (IMEI). Every mobile phone has a 15-digit number, also known as an IMEI number that is globally unique. This number could either by found underneath the GSM mobile phone's battery or by dialling *#06# on a device's keypad [18]. GSMA also ensures that devices manufactured and sent to market are compliant with the requirements of the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). In 1996, GSMA launched an initiative to have stolen mobile handsets blocked on the basis of the International Mobile Equipment Identifier (IMEI) [17] [19]. The issue of mobile phone theft is certainly not of the industry's creation, yet industry forms part of the solution. Blocking or blacklisting the IMEIs of stolen or lost mobile phones would render them useless, and thereby reduce their value on the black market. The consideration to blacklist stolen mobile phones from networks has been around for 2 decades, but is hardly implemented regionally and more so internationally [20].

2.3. International and Regional Mobile Phone Theft Interventions

- Notably, the United Kingdom have been ahead with efforts to combat cell phone theft. A Crime Reduction Charter was signed in 2006 and it acknowledged the future commitment of the mobile phone industry towards collaboration with law enforcement agencies to ultimately address phone theft. This charter was spearheaded by the Mobile Industry Crime Action Forum (MICAF), which included mobile network operators, UK retailers, and some handset manufacturers. The first country to have had all mobile network operators effect IMEI blocking or blacklisting was the UK, followed by Australia [18].Australian authorities and the police have the 'Mind Your Mobile' campaign aimed at reducing the incidence of theft or loss of mobile phones. Blocking or blacklisting of handsets based on the IMEI number completed in March 2003 and prevents stolen handsets from being used on any network in Australia. Blocking the IMEI number renders a handset inoperable. In 2003, Australia’s GSM network providers – Vodafone, Telstra and Optus – agreed on a response time of 36 hours for blocking or unblocking stolen and found handsets respectively. These three mobile operators exchange lists of lost or stolen mobile phones. The Australian Mobile Telecommunications Association (ATMA) offers an online portal at which those desiring to buy second hand phones could verify whether a mobile phone was reported lost or stolen and subsequently blocked from use by the network carriers. Roughly about 50, 000 phones per year are unblocked at owner's request on account of being returned.A projected 3.1 million customers in America experienced theft of a mobile phone in 2013 [21]. Recognizing that mobile device theft is a key concern facing law enforcement agencies, customers and other stakeholders in the mobile device ecosystem, a Mobile Device Theft Prevention (MDTP) Working Group was created through the Technological Advisory Council (TAC) of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) of the United States Government. The MDTP Working Group's mandate was to examine the prevalent problem of cell phone theft and formulate recommendations to the Federal Communications Commission by end of 2014 [22]. The Mobile Device Theft Prevention Working Group collected law enforcement from 21 police jurisdictions as well as FBI crime data - and estimated at least 10% of all thefts and robberies committed in the United States in 2013 were connected to theft of a mobile device [22].As the use of smartphones has grown in Latin America, so have incidences of device theft increased [23].

| Figure 1. Latin America Phone theft statistics [23] |

2.4. Existing Initiatives in Latin America and Other Regions

- In Brazil, the Police could invoke a report of a stolen device. In Ecuador, a user must first report a theft for the blocking process to be initiated. In Chile, whitelists address the issue of device registration prior to selling of imported devices/handsets. Devices are linked to national public registry entry pointing to the owner. The successful implementation of IMEI blacklists hinges on strong and precise crime reporting mechanisms. This may not be easy especially in countries where a bulk of crimes go unreported. A recent study in Brazil established that only 51% of phone theft victims reported to the Police [23]. Notwithstanding the execution of blacklists and whitelists in Peru, an approximated average of 250 devices are stolen per hour - translating to 6,000 stolen devices per day. Phone theft incident reported to the Columbian police in the initial half of 2017 were as low as 4% [23]. Thieves circumvent blacklist systems by either shipping stolen devices in neighbouring regions and countries or altering IMEIs.The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) observed that the theft of handsets was a major problem affecting cities. To this effect, TRAI instituted measures to work out a framework by which theft of mobile phones could be dissuaded and Consultative Paper No.2/2004 was issued on 8th January 2004 to invoke engagement by various stakeholders [24]. Handset cost was identified as a chief inhibitor for low-end customers, with a gap in mobile phone prices clearly noted between the legitimate and grey markets. The grey market consists of smuggled, lost and or stolen handsets. Therefore, action had to be taken to safeguard consumer interests by disincentivising the purchase of handsets from the illegal grey market. The blacklisting of handsets became a major consideration of the Telecommunication Regulation Authority of India (TRAI) and it was proposed to be done based on the International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI). The next phase would be to ensure sharing of IMEI numbers of stolen or lost handsets among all mobile network operators in the country and denial of service to blacklisted handsets by all operators in a bid to effectively address the theft problem. But as noted by Yatin Jog et al operators in India implemented Equipment Identity Registers (EIRs) in isolation and thus stolen phones could still be usable if one simply changes SIM cards since operators were not sharing information [25].

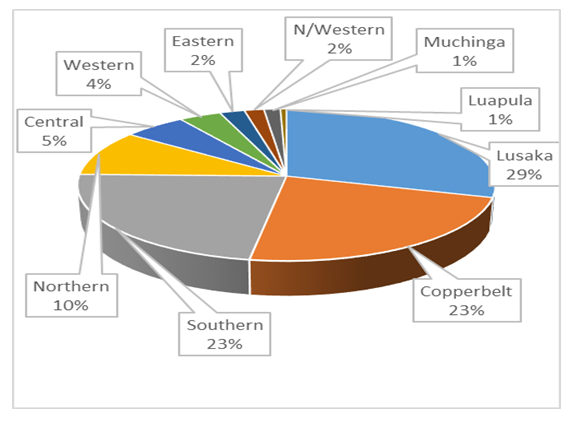

3. Methodology

- Two main approaches are applicable when conducting research – quantitative and qualitative. Qualitative research focuses on the social constructivism paradigm and sanctions the socially constructed nature of reality. The qualitative approach puts no emphasis on data in numerical form and thereby does not stress the analysis of data by use of statistical techniques. Quantitative research, on the other hand, is concerned with the gathering of data and translating it into numerical formats so that analyses and deductions can be drawn with ease [26]. The qualitative and quantitative methods could complement each other, so this study adopted a mix of the two.Both primary and secondary data sources were considered in this study. Primary data was obtained in the form responses to structured and semi-structured questionnaires that were distributed to four categories of respondents. These respondents included the Zambia Police as the law enforcement wing, Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) as the service providers, ZICTA as the regulator as well as the general populace who are the users. Open-ended and closed-ended questions were included in these questionnaires in order to capture both the qualitative and quantitative responses. Further, online survey was conducted through Google Forms, which was used in a way used to aid in the reception of responses to the questionnaire designed for the general populace. In terms secondary data, the study methodically evaluated data from previous studies that considered GSM theories and concepts for a possible solution to the challenge of mobile phone theft. The literature examined encompassed journal articles from reputable publishers, proceedings and publications, material from standards bodies like the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and the GSM Association (GSMA).Particularly, the Researcher conducted face-to-face interviews mainly with ZICTA, MTN and ZAMTEL. The course of these interviews was generally guided by the questionnaire designed for Mobile Network Operators (MNOs).Population is the total compilation of elements about which we wish to make inferences [27]. The population considered for this study was that of Lusaka Province. As seen from the baseline study results, Lusaka province recorded the highest number of mobile phone theft incidents. Further the Headquarters (HQs) for the Mobile Service Providers, ZICTA and Police are in Lusaka. Based on the statistics obtained from Central Statistical Office (CSO), Lusaka has a population size of approximately 1.7 million.Based on this estimated Lusaka population, a sample of 450 respondents were selected and given questionnaires to fill in. The sample size was arrived at using an Online Sample Size Calculator which guided that a minimum of 385 responses would have to be secured if a desired confidence of 95% and marginal error of 5% was desired [28]. In determining the target respondents, a multi-stage cluster sampling method was used to select respondents from the four different zones of Lusaka namely Chilanga, Chongwe, Kafue and Lusaka. The sampling design was appropriate for a large sample such as for this study. In this design, the study proportionately clustered the respondents according to their zones. After clustering them, a systematic random sampling of households and individuals was then used to select the final respondents.Further, in selecting the other stake holders from the Police, ZICTA, and service providers, purposive sampling was employed in which subjects were purposively selected based their expert knowledge on the subject.Data was entered, analysed and presented using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists version 16 (SPSSv16). The data was analysed using Univariate analysis only. Additionally, Microsoft Office Excel 2016 also employed for translating some of the data into graphical representations like pie charts and bar charts.

4. Research Findings

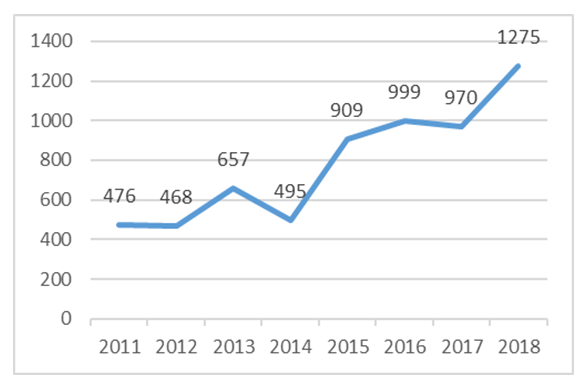

- The main objective of this study was to profile the prevalence of cell phone thefts in Zambia and to explore possible solutions to mitigate the challenge. A baseline study undertaken confirmed that phone thefts have persistently increased over the past years. In the year 2011, 476 phone thefts were reported to the Police. By end of the year 2018, this number had increased to 1,275, representing a phone theft increase percentage of 267.9%.

| Figure 2. Reported Phone Thefts Countrywide |

| Figure 3. Phone Theft by Province |

| Figure 4. Phone Theft in Lusaka Province |

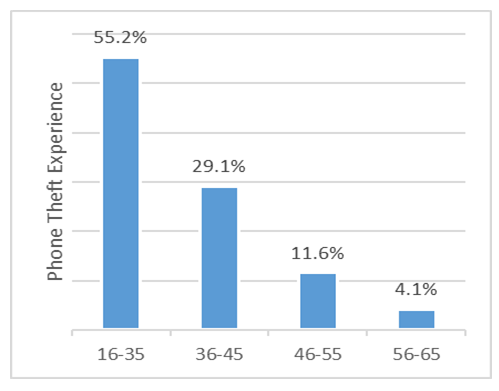

| Figure 5. Phone Theft in relation to Age |

|

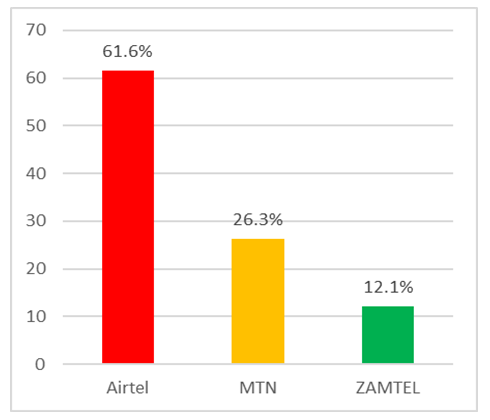

| Figure 6. Theft Victims According to Service Provider |

5. Discussion

5.1. Existing Framework for Addressing Mobile Phone Theft in Zambia

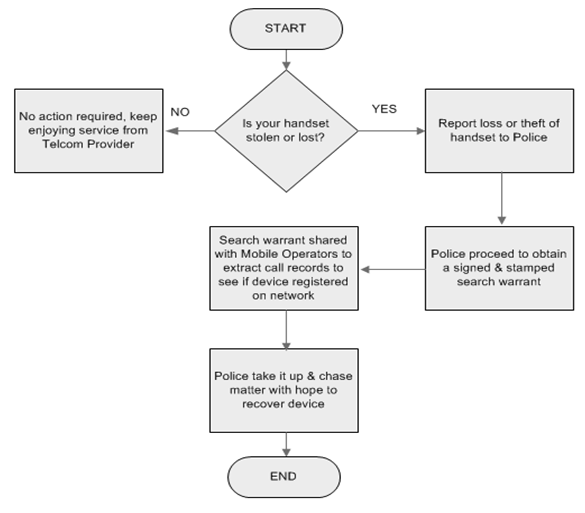

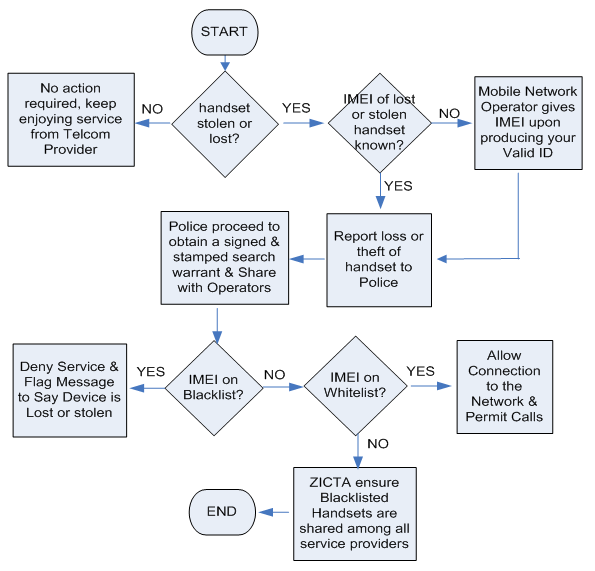

- There is no existing requirement or mandate wherein Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) ultimately blacklist lost or stolen handsets to prevent them from being used. If at all blacklisting of handsets was done by a single Mobile Network Operator, users would simply circumvent this by switching mobile service providers because operators are not currently exchanging blacklists. The process is open-ended with no assurance that the Zambia Police (Law Enforcement Wing) would actually attempt to pursue the issue any further following the report of the theft.This study has established that all 3 mobile network operators currently operating in Zambia do have GSM Systems Features that support blacklisting of handsets/phones based on the IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identifier). ZICTA will come to the centre stage to facilitate the exchange of blacklists so that a handset/phone on this list would not be usable on any of the 3 providers’ network.

| Figure 7. Existing Framework for addressing Phone Theft in Zambia |

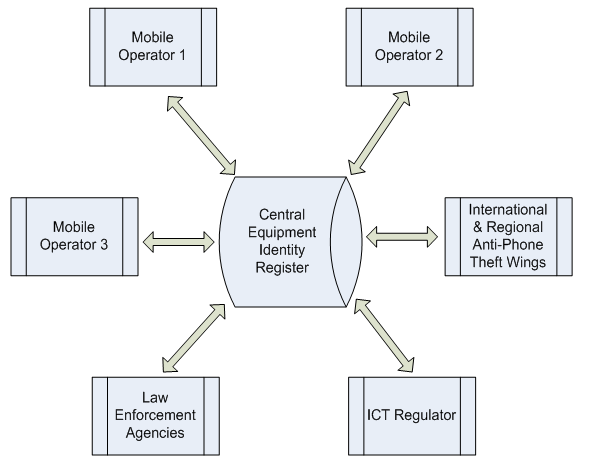

5.2. Proposed Framework for Addressing Mobile Phone Theft in Zambia

- The introduction of blacklists would ultimately render stolen phones unusable and, with user education, considerably reduce the motivation for which criminals steal phones. ZICTA would set up and Manage Central Identity Equipment Register wherein all providers exchange blacklists instantly. This could leverage on database migration tools readily available for the easy exchange of blacklists by mobile service providers [29]. This move would not only reduce in-country phone thefts, but also prepare our nation to participate in Regional (SADC) initiatives aimed at combating mobile phone theft.

| Figure 8. Proposed Framework to address Phone Theft in Zambia |

| Figure 9. Enhanced Collaboration for Exchange of IMEI Blacklists |

6. Conclusions

- This study was conducted to determine the prevalence of phone thefts in Zambia, specifically in Lusaka Province. The study established that the prevalence of phone thefts in the country is very high at 67%. The findings revealed that these thefts were more prevalent among the young and middle aged people. Further phone thefts or losses were experienced mostly with Samsung and Nokia phones, as well as among the Airtel subscribers. The study revealed that this was as result of weaknesses in the existing framework by which the players in the telecommunication industry; namely the regulator (ZICTA), the Police and the Mobile Network Operators interact or exchange. The study suggested a new framework that addresses the weaknesses observed with the current system. This proposed system has advocates for the creation of a Central Equipment Identity Register (CEIR) to be hosted and managed by ZICTA for the facilitation of exchange of IMEI blacklists between and among mobile network operators such that lost/stolen handsets would be rendered unusable. It is highly recommended that the new framework be adopted to poise our country for participation in Regional Efforts and Initiatives aimed at addressing the challenge of mobile phone theft.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- My sincere gratitude goes to my supervisor, Dr. Simon Tembo, for the fatherly guidance and encouragement he gave me during the process of working on this research. I thank the three mobile network operators in Zambia as well as Zambia Police and the ICT regulator, ZICTA. Finally, I would like to express my very profound gratitude to my wife Annette, my daughter and son, my beloved parents, and brothers for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this study. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML