-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Automation

p-ISSN: 2163-2405 e-ISSN: 2163-2413

2016; 6(4): 85-93

doi:10.5923/j.jmea.20160604.03

Failure in Engineering of the Crashed Flight 3407 Aircraft

Kevin Carr, Robert Jonson, Sean Murray, Gurinder Singh, Mark Stiegler, Maxwell Turner, Christopher Walker, Satbir Wraich, Dariush Zadeh

Department of Mechanical Engineering Technology, Erie Community College, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Dariush Zadeh, Department of Mechanical Engineering Technology, Erie Community College, NY, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

On February 12, 2009 Colgan Air Flight 3407 flying from Newark, NJ to Buffalo, NY entered an aerodynamic stall and crashed into a house in Clarence Center, NY at 10:17pm [1, 2]. This article reviews the failure in engineering of that aircraft including its low power to weight ratio, and its inadequacy with respect to the deicing system of wings in bad weather condition. Also the article discusses the inherently flawed propeller driven aircrafts such as the one used for flight 3407 versus aircrafts with jet engines, the intermittent deicing system of propellers, as well as other factors centered on that fatal crash. Theory of flight is briefly reviewed along with how ice buildup on wings can dramatically increase the drag and reduce the lift of airplane. All underlying causes of the accident are summarized along with suggestions for avoiding this type of accident in future.

Keywords: Machine Design, Product Design, Failure in Engineering, Aeronautics, Design Review

Cite this paper: Kevin Carr, Robert Jonson, Sean Murray, Gurinder Singh, Mark Stiegler, Maxwell Turner, Christopher Walker, Satbir Wraich, Dariush Zadeh, Failure in Engineering of the Crashed Flight 3407 Aircraft, Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 85-93. doi: 10.5923/j.jmea.20160604.03.

Article Outline

1. The Story [1, 2]

- Flight 3407 [1, 2] left Newark, New Jersey on February 12, 2009 in cold weather condition and was expected to land in Buffalo, New York around 10:20 PM. The plane had been flying from Newark, New Jersey for the past hour when it reached just miles of the Buffalo International airport. Weather conditions at the time was reported as a wintry mix in the area, with light snow, fog, and winds of about 17 miles per hour (15 knots) [1]. The crew had discussed significant ice buildup on the plane while the deicing system had been on during the flight. Two other planes had also reported icy conditions on their wings and windshield. The plane had been on autopilot and was turned to manual for descent. The captain requested to lower from 16,000 feet to 12,000 feet which was cleared. Soon after, they were cleared for 11,000 feet elevation. The aircraft crashed 41 seconds after the last transmission. As the plane reached about five miles from the airport, the pilot started to reduce the speed and descend by extending the flaps and deploying the landing gear. Soon after extending the flaps, the plane started to pitch and roll and going out of control probably due to the ice buildup and the inadequate deicing system. The speed decreased to 145 knots (269 km/h) and as the flaps transitioned past the 10 degree mark, the speed further dropped to 135 knots (250 km/h). In about 6 seconds later, the aircraft's speed was dangerously low of about 131 knots (243 km/h). The pilot naturally tried to keep the airplane in control by keeping it in upward position. Then the airplanes stick pusher went on to prevent the aircraft from stalling and did not allow pilot to push the stick forward for the descent. The captain overrode the stick pusher to keep the airplane in upward position. During the final moments, the aircraft went into a yaw and pitched up at an angle of 31 degrees, before pitching down at 25 degrees. It then rolled to the left at 46 degrees and snapped back to the right at 105 degrees. At that time, the plane had lost the total control and in the next 25 seconds went almost straight down and crashed into a house in Clarence Center, NY. There were a total of 50 fatalities including all 45 passengers, the 4 crew members, and one of the three people in the house were killed. According to the final report of the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the accident's probable cause "was the captain’s inappropriate response to the activation of the stick shaker, which led to an aerodynamic stall from which the airplane did not recover” which thereafter led to the crash [1]. The NTSB further added the following contributing factors as: (1) The flight crew’s failure to monitor airspeed in relation to the rising position of the low- speed cue, (2) The flight crew’s failure to adhere to sterile cockpit procedures, (3) The captain’s failure to effectively manage the flight, and (4) Colgan Air’s inadequate procedures for airspeed selection and management during approaches in icing conditions [38].

2. Theory of Lift and Drag [3-16]

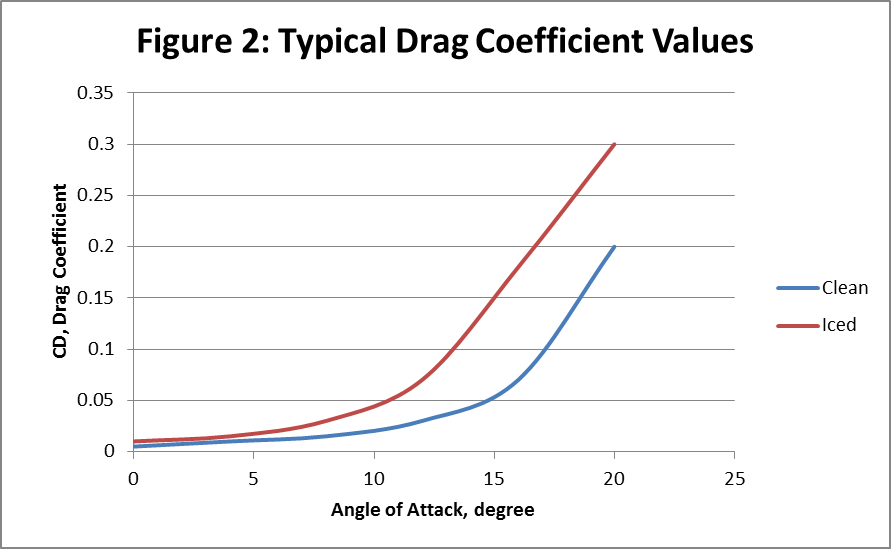

- The original inspiration for the design of airfoils came from the wings of birds. An airfoil is used to describe the cross-sectional shape of an object or wing, when moved through air, creates an aerodynamic force [3-11]. Airfoils/wings were employed on aircrafts to produce an upward force (lift) to keep them airborne. The lift is greater or equal to the downward gravity force of weight of airplane. According to Bernoulli's Principle, the air passing over the top of a wing must travel further and hence faster that air the travelling the shorter distance under the wing in the same period but the energy associated with the air must remain constant at all times. The result of this is that the air above the wing has a lower pressure than the air below the wing and this pressure difference creates the lift.The lift is accompanied by another force which is called “Drag”. Drag represents the air resistance force against the wing as it forces its way through the air. To overcome the drag, airplanes have engines to produce a forward force which is called “thrust”. So aircrafts are kept in the air by the forward thrust of engines. Lift and drag is dependent on the effective area of the wing facing directly into the airflow as well as the shape of the wing. They are also dependent on the density of the air and velocity. Typical formulas to model and calculate lift and drag of an airfoil is given as:

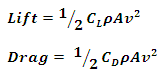

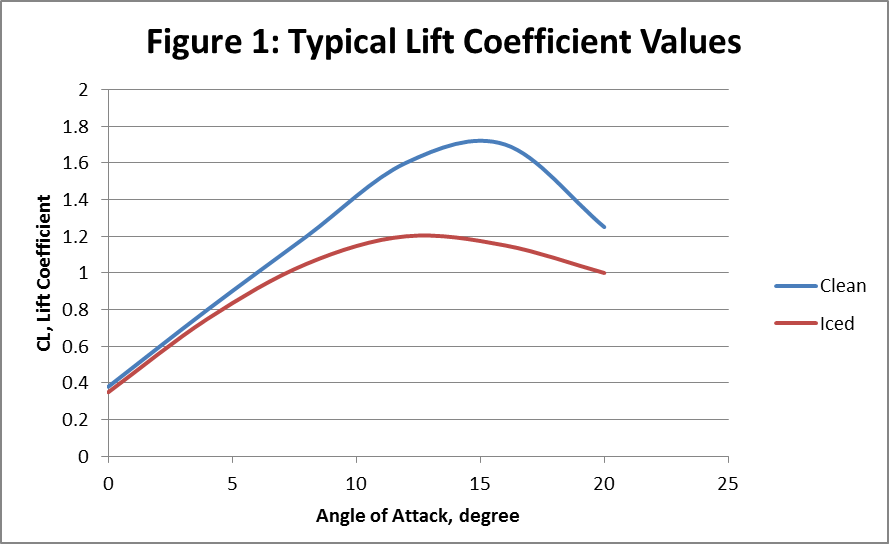

The parameters in the formulas are CL, which is the Lift coefficient; CD, the drag coefficient; ρ the density of air; A, the projected area of airfoil, and finally v which is the velocity airfoil with respect to air.The amount of the lift and drag are dependent on the angle of wings and airplane which is called the “angle of attack”. Lift Coefficient versus the angle of attack has a peak that generally is referred as the “Stall” point [12-14] (Figure 1 & 2). As the attack angle of wings increases, the lift coefficient would increase until it gets to the stall point. From that point on if the angle of attack is further increased, not only the lift coefficient and therefore lift will not increase anymore but it would start to decrease fast. Similarly, with passing the stall point (/angle), the drag coefficient and the drag force (air resistance) become so large that airplane engine generally cannot sustain the speed and the speed of airplane will drop fast and therefore a crash will be imminent. Also, stall is being used as the “stall speed” referring to the speed that the magnitude of generated lift becomes less than the weight of airplane which causes the airplane to descend and get out of control. With a powerful engine and a reasonable angle of attack, pilots can overcome the stall condition and bring back the airplane under control.

The parameters in the formulas are CL, which is the Lift coefficient; CD, the drag coefficient; ρ the density of air; A, the projected area of airfoil, and finally v which is the velocity airfoil with respect to air.The amount of the lift and drag are dependent on the angle of wings and airplane which is called the “angle of attack”. Lift Coefficient versus the angle of attack has a peak that generally is referred as the “Stall” point [12-14] (Figure 1 & 2). As the attack angle of wings increases, the lift coefficient would increase until it gets to the stall point. From that point on if the angle of attack is further increased, not only the lift coefficient and therefore lift will not increase anymore but it would start to decrease fast. Similarly, with passing the stall point (/angle), the drag coefficient and the drag force (air resistance) become so large that airplane engine generally cannot sustain the speed and the speed of airplane will drop fast and therefore a crash will be imminent. Also, stall is being used as the “stall speed” referring to the speed that the magnitude of generated lift becomes less than the weight of airplane which causes the airplane to descend and get out of control. With a powerful engine and a reasonable angle of attack, pilots can overcome the stall condition and bring back the airplane under control. | Figure 1. Typical Lift Cofficient Values |

| Figure 2. Typical Drag Cofficient Values |

| Figure 3. Lift, Drag, and Angle of attack [15] |

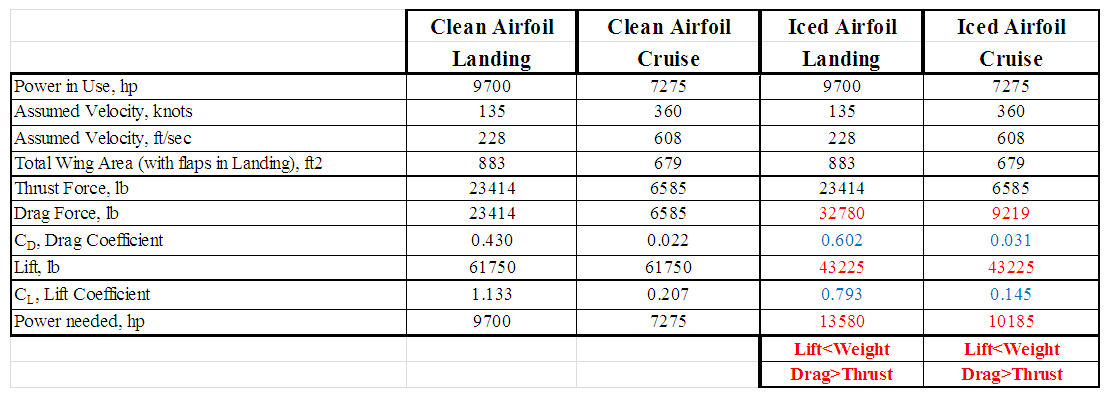

2.1. How Ice Build-up can Increase the Drag and Decrease the Lift [17-22]

- As rain impacts the airplane in cold weather, it freezes on it. Ice generally builds up on the frontal surfaces, leading edge of the wings, the nose and the tail surfaces. The rain may also freeze further back on the wing where ice cannot be effectively removed. The ice alters the shape of the wing changing the airflow over the wing and tail, reducing the lift force that keeps the plane in the air. It can also increase the drag force larger than the thrust of engines and potentially causing aerodynamic stall which results in loss of control. Experiments have proved that with an ice-build-up on the wings the “Lift Coefficient” will drop and “Drag Coefficient” will increase [17-21]. Reportedly, ice-build-ups on airplanes could drop the lift about 30%, and could increase the drag about 40% [22]. A typical change in the Lift and Drag Coefficients is shown in the Figures number 1 and 2. A small amount of ice on the aircraft would increase the weight of aircraft, and could reduce the lift, and increase the drag significantly.

2.2. Power to Weight Ratios of Airplanes [23, 24]

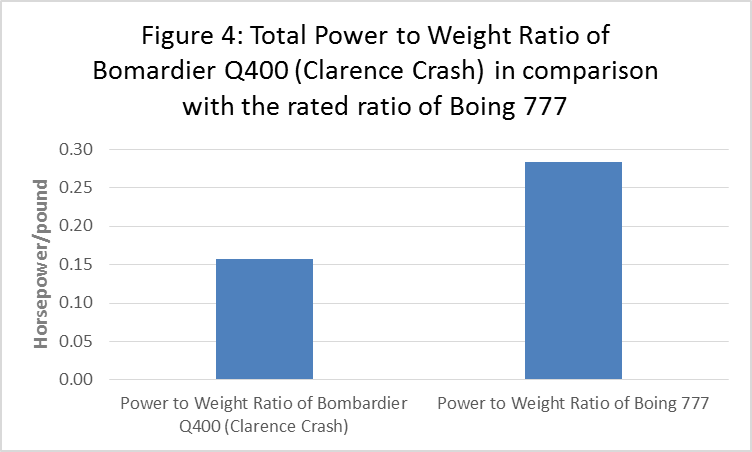

- In the aftermath of Flight 3407 crash many were questioning whether the Bombardier Q400 was even the correct choice of aircraft for the existing weather conditions occurring at the time. So the power to weight ratio of the Flight 3407 airplane (Bombardier Q400) was compared to the same ratio of commercial Boeing 777 [23, 24]. The Bombardier Q400 was equipped with two propeller engines with a maximum continuous power of 4850 HP for each, which added up to a total of 9700 HP for the entire aircraft. It had a maximum landing weight at 61,750 lbs creating a power to weight ratio of about 15.71%. On the other hand, Boeing 777 has two turbojet engines, each creating 110,000 HP, which adds up to a total power of 220,000 HP for the entire aircraft. It has a maximum landing weight of 775,000 lbs which creates a power to weight ratio of about 28.39%. Although the Boeing 777 is significantly larger and heavier than the Q400, it has a much larger power to weight ratio with respect to Q400 bombardier. Higher power of the Boeing gives it a greater maximum speed and could stand better in the given weather conditions. Boing would have had a much greater chance or even undoubtedly would have succeeded in surpassing the ice and frost on its surface due to its massive size, power and more advanced de-icing systems. Figure 4 presents a graphical view of the two airplanes with respect to their power-to-weight ratios.

| Figure 4. Total Power to Weight Ratio of Bomardier Q400 (Clarence Crash) in Comparison with the Rated Ratio of Boing 777 |

3. Mathematical Models

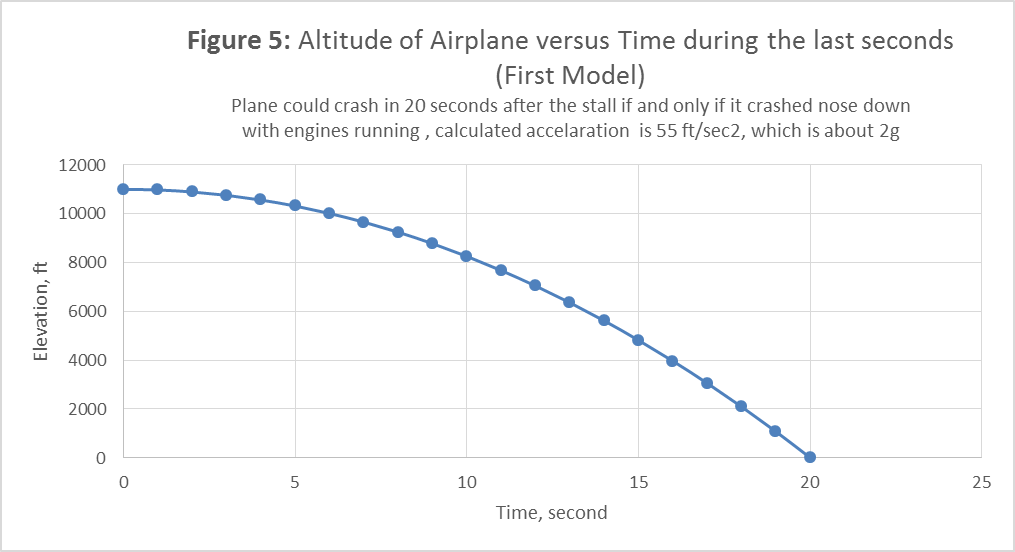

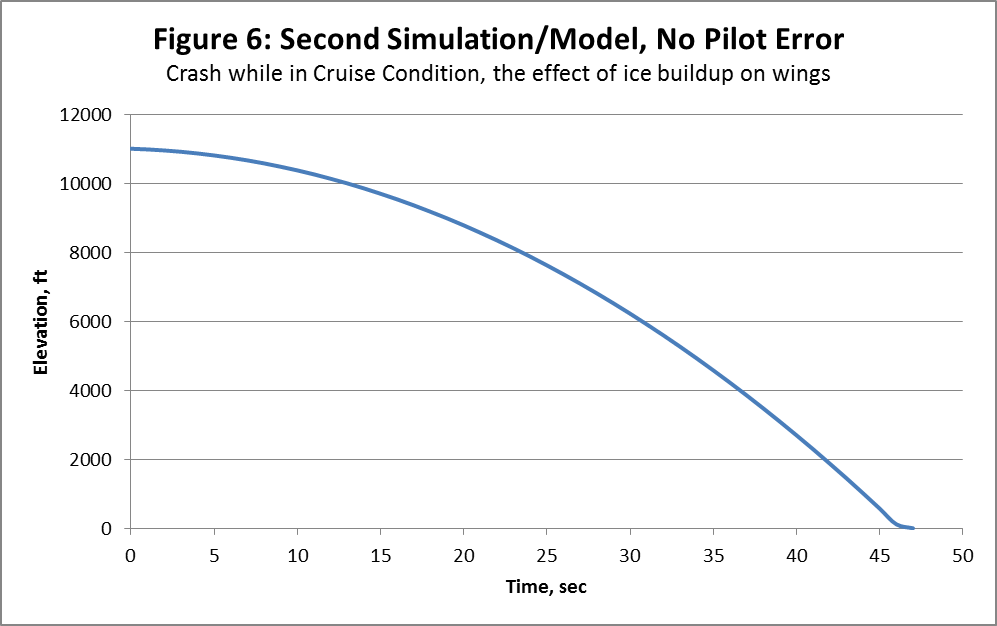

- Two mathematical models were built to better understand the cause of crash. The first model was to investigate the last 20 seconds before the crash. Reports seemed to indicate that airplane crashed down in about 20 seconds from an elevation of 11000 ft and the passengers experienced a 2G gravitational acceleration1 during the crash. So a simple mathematical/physical model was built to investigate the possibility of that kind of crash. The model showed that there was a possibility of that kind of crash as long as the airplane had crashed nose down. In free falls, objects do not accelerate more than 1G. And the only way to have a 2G acceleration is a nose down orientation in which the engine and propeller could have helped to reach a 2G acceleration. Our calculation showed that an airplane in a dive mode with nose downward could crash in about 20 seconds from 11000 ft elevation with a calculated acceleration of about 55 ft/s2, which is about 2G. Figure 5 shows the elevation of crashing airplane with respect to time during the last 20 seconds.

| Figure 5. Altitude of Airplane versus Time during the last seconds (First Model) |

| Table 1. Numerical Presentation of Second Model |

| Figure 6. Second Simulation/Model, No Pilot Error |

3.1. De-icing Systems on Airplanes [25-32]

- De-icing systems on airplanes have the job of preventing or removing ice buildups on aircraft surfaces, particularly the leading edges of the wings and other forward facing surfaces. Electro-thermal systems use wires that are run through the wings. When electricity is applied to the wirings, it generates heat that can remove or prevent ice buildup. The circuit heat the material in contact with the ice and the force of the wind removes the ice from the wing. Running the circuit continuously will prevent the ice from forming (anti-ice) or the system can be operated as needed to remove any ice that has built up (de-ice). Newer electro-thermal systems, such as ThermaWing, use newer materials such as graphite foil and carbon nanotubes that are very light weight and use a lot less energy. Electro-thermal systems are used on many different aircraft from general aviation and commercial jumbo jets. Bleed air systems use hot air from the jet engines to remove the ice from leading edges. The hot air is run through tubes routed through the flight surfaces of the aircraft. This keeps the surfaces warm enough to prevent ice buildup. Bleed air systems are currently used in most of the larger commercial jets. Electro-mechanical deicing systems use mechanical devices inside of the aircraft to create vibrations large enough to knock the accumulated ices off of the flight surfaces. It can be used in conjunction with an electro-thermal system in a hybrid electro-mechanical expulsion deicing system. The electro-thermal system runs continuously as anti-icing on the leading edges of flight surfaces and then the electro-mechanical actuators knock off any ice that has accumulated on the other parts. TKS Ice Protection is an anti-ice system. It uses a glycol-based fluid that does not freeze and pumps it through tiny holes drilled into the forward facing flight surfaces to heat them. This prevents any ice from forming. This liquid coming from the holes does not affect the performance of the aircraft, but any added weight to an aircraft is undesirable. Passive de-icing and anti-icing systems do not use electricity or mechanical force to prevent ice buildup.Hydro phobic materials can be used to repel any water that comes in contact with the surface to prevent them from freezing on airplane. Pneumatic De-icing Boots is the system that was installed on Colgan Air Flight 3407. It is made up of rubber boots that are installed on the leading edges of the aircraft. When the ice build-up is detected the boots are filled with air in the hopes that the changing shape dislodges the ice. Sometimes the boots have multiple chambers that can be filled at varying times so the ice cannot build up in weak spots. This system does have some drawbacks such as if the ice is not thick enough it can cause ice to be pushed back to a part of the wing without the pneumatic boot.

3.2. Propeller Airplanes – Inherently Flawed [33, 34]

- Bombardier Q400 was equipped with propeller turbo engines. Propeller aircraft and their pilots have to compensate for many forces in order to go in a straight line during takeoff/landing and during flight. The air does not flow horizontally, it flows in a twisting helix around the wings and fuselage. If we assume the propellers are moving in a clockwise motion, as seen from the back of the plane, the airplane would tend to yaw and turn counter-clockwise. P-Factor refers to the uneven air flow and thrust created by the propeller at different points in the propellers rotation when the airplane is at a high angle of attack and not horizontal. As the propeller descends in its clockwise rotation it has a higher angle of attack to the oncoming air than the ascending left side. This cause the right side of the propeller to move more air and create more thrust and causes the plane to yaw to the left. Colgan Air Flight 3407 had 2 turoprop-engines rotating in opposite directions in an effort to balance these forces. Icing changes the aerodynamics of the plane in uneven and unpredictable ways and can cause these forces to become unbalance and have a greater effect on the stability of the aircraft.

3.3. Turboprop Engine vs. Turbojet Engine [35-39]

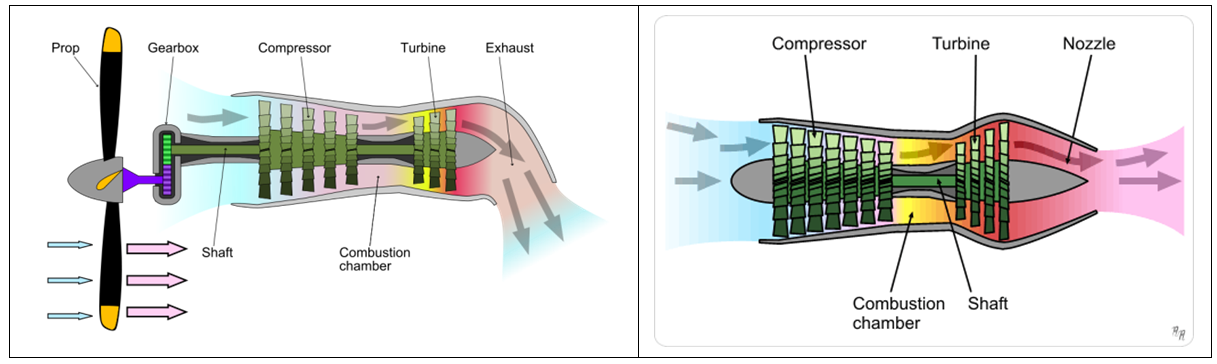

- Turboprop engines, like the two installed on Colgan Air Flight 3407, use gas turbines to produce power and rotate propellers. Rotating propellers then generate the thrust. The thrust created by the exhaust gas is negligible in this type of engine. On the other hand, turbojet engines do not have propeller and are much stronger than turboprop engines. The exit exhaust gases in this type propel the airplane directly and efficiently without any problem. Figure 7 shows differences of a turboprop engine with respect to a turbojet.

| Figure 7. Schematic diagram of a turboprop (left) versus a turbojet (right) [35, 36] |

4. Underlying Causes of Accident

- It seems that NTSB and media mostly blame pilots for the crash of Colgan Air Flight 3407 in Clarence for their lack of experience as the main cause of the crash. Nevertheless while experience may have played a part in the events that eventually led to the crash, there are many other factors that were out of the control of the pilots. Some of the factors which could have contributed to the crash include: the lack of a proper de-icing system on the aircraft, the use of a propeller type plane and the inherent flaws that come with using this type of plane, and the lower power-to-weight ratio of the Bombardier Dash-8 Q400 when compared to other modern aircrafts. Of course we need also to consider that the pilots may not have received the proper training to deal with this type of situation.Looking more carefully at the pneumatic de-icing system of the Q400, it is obvious that the system had inefficiencies. For instance, the de-icing boots only covered the leading edges of the wings and tail and they neglected the ice that could build up on the other parts of the plane. This is known as re-freezing and occurs when the ice that is broken up on the leading edge of the wing is not properly carried away from the aircraft and is allowed to refreeze on the surfaces behind the de-icing boots. In general, ice accumulations no thicker or rougher than a piece of coarse sandpaper can reduce lift and increase drag. Larger accretions can reduce lift even more and can increase drag by 80% or more. Our modeling and calculations with 30% drop in lift and 40% increase in drag due to icing showed that the airplane could not be saved under any circumstances.The use of inadequate heating of propeller blades was another problem with this airplane. The propellers on a Q400 had an anti-icing system that used electricity to prevent formation of ice on the propeller blades. Only 70% of the blades were covered by the heating element, and as with the boots on the wings and tail, it only covered the leading edge of the blade. Although all 6 blades on one propeller were heated at once, only one propeller was heated at a time in order to save energy. This could pose a problem since as one propeller was heated, the other propeller was accumulating ice. So having unheated side for propeller could have led to an increase in drag and instability under dangerous weather condition of Buffalo, NY.The Flight 3407 Bombardier Dash-8 Q400 had another problem of low power-to-weight ratio when compared to other modern aircrafts. The two PW150A propeller engines that powered the Q400 created a power-to-weight ratio of 15.71% at max power for a maximum weight of 61,750 lbs. When compared to Boeing 777 which is powered by twin turbofan GE90-115B engines, one can see that even with a heavy weight of 775,000 lbs, they have higher power-to-weight ratio of 28.39%. That’s almost twice the power-to-weight ratio of Bombardier with over 12 times the weight. Additionally, the added weight of ice could have put more pressure on the engines. As an insight, one can assume just one inch of accumulated ice on the 679 ft2 projected surface area of airplane. Then the volume of the ice would be around 1.6 cubic meter with an added weight of 3185 lb ice on the airplane. And just for reference, 1 m3 of ice weighs just under a metric ton, which is about 1,984 lbs. Layers of ice could have created not only drastic increase in drag and had altered the air flow pattern on the wings which could have decreased the lift, they could have also made the airplane much heavier than it was.Of course not all the blame can be put on the machine and some has to go to the handlers. It was inferred that there was a clear lack of experience for the pilots and lack of attention to dangerous situation. Apparently, pilots were “talking shop” prior to the crash according to the NTSB report. But one cannot put all of the responsibility for lack of training on the shoulder of pilots themselves. Most of the fault needs to go to the employers, Colgan and Continental Airlines for the lack of proper training of pilots. For example, a tail stall is a situation less familiar to many pilots and the required action is completely opposite to that of the more common wing stall which most pilots are trained for. The tail section of the aircraft can collect up to 2 to 3 times more ice than the wings during ice accumulation. One need to keep in mind that the tail section of the plane is not visible to the pilots during flight and therefore more training and experience is required to handle that kind of stall.

5. Conclusions

- There is not one simple reason for the crash of flight 3407. But the study group believes that the aircraft designers/manufacturing company, de Havilland Canada, should be mainly blamed for their bad engineering/design/ product. The crash happened due to many technical factors with the most important one to be the inadequacy of airplane for bad weather conditions. The power to weight ratio of airplane was low and about 15.71% in comparison to the power to weight ratio of Boeing 777 to be around 28.39%. The airplane was using an inefficient deicing system (Pneumatic De-icing Boots), which no way could handle the massive ice built-ups in Buffalo area. This system is made up of rubber boots that are installed on the leading edges of the aircraft. When the ice build-up is detected, the boots are filled with air in the hopes that the changing shape of boots would dislodge the ice. The next sticking factor was the use of the inherently flawed turboprop engines instead of turbojet engines. The thrust created by the turboprop engines is much less than the turbojet engines and they create a reaction torque on the body of airplane due to the propeller action which needs to be neutralized. Also, deicing of propellers on this kind of airplane is not generally done continuously in order to save electricity. Our calculations with the assumption of 30% drop in the lift coefficient and 40% increase in the drag coefficient due to ice build-up showed that sustaining the airplane in air under those conditions could be impossible and beyond the ability of pilots. The group thinks that the carrier (Continental Airlines) and its subcontractor (Colgan Air) companies are the next ones to be blamed for the crash due to their poor supervision, poor choice of airplane (Bombardier DHC8-402 Q400), and the approval of the flight under extreme bad weather conditions. The cheaper airplanes for the short fights end up costing the airlines more in lawsuits than the cost of deploying a safer, stronger, and more ice-ready aircrafts for the flight. The airlines that operate under extreme bad weather conditions have the final say with respect to flying, or not flying. At least, they could have delayed the departure time for the Flight until they knew the weather had cleared up, which could have ultimately changed the outcome of the flight. The group thinks that the carrier and its subcontractor companies probably knew well about the capabilities and deficiencies of their airplane since they were continuously using that kind of airplane. Propeller planes much like carburetor car engines are out dated and there are much better and safer engines to handle unpredictable weather conditions. The rubber boot deicing system used on the Q400 only could help to de-ice the leading edge of the aircraft wings.Finally, the pilots hold the least of the fault because they probably did not have the right trainings, and experience and should have focused more on the weather situation.

Suggestions for Future [40, 41]

- 1- It should also be suggested that only certain types of aircraft fly in extreme weather conditions. The first suggestion would be that only planes using turbo jet engines or turbo fan engines be used instead of propeller turbo-engines. However this option would cost more money to the airline and passengers. Most turbo prop aircraft are used for shorter flights with fewer passengers than turbo-jet and turbo fan aircraft. Additionally turboprop aircraft are more cost effective at lower speeds and lower altitudes, whereas turbofan engines are more effective at higher speed and higher altitude. It could be argued that additional cost of operating turbo jet and turbo fan aircraft in extreme weather conditions would be ok due to the gains for the increased safety of flights.2- The power-to-weight ratio of airplanes flying in bad weather should be high enough and weaker airplanes should not be utilized for bad weather conditions.3- It is suggested that airplane flying in bad weather condition, should be equipped with two different types of deicing systems. Flight 3407 was equipped with a pneumatic deicing system that used pneumatic deicing boots on the leading edges of wings and tail for inflight de-icing. The rubber coverings are periodically inflated, causing ice to crack and flake off. Once the system is activated by the pilot, the inflation/deflation cycle is automatically controlled. It is known that anti-icing system was activated by the pilots of Flight 3407, however the Flight Data Recorder from the aircraft did not record whether the system actually worked or not. In the event that the primary system did not work, ice build-up on the aircraft could have been prevented by using the secondary deicing system. 4- Finally, only experienced and well-trained pilots should be used for extreme weather conditions. One way to increase a pilot’s experience level for such adverse conditions is the use of pilot training flight simulators [40, 41]. Today flight simulation is widely used to enhance aviation safety by providing practice for cockpit procedures and the replication of in-flight scenarios. The Federal Aviation Administration says the loss of control in flight accidents is a recurring causal factor and the pilot’s inappropriate reaction to impending stalls and full stalls should be corrected by proper trainings. Moreover, the agency asserts that some pilots may not have the required skills or training to respond appropriately to an unexpected stall. Full Flight simulators can be used to re-create conditions similar to those experienced by the flight crew of Flight 3407, and allow the training pilots multiple attempts at recovering from the stall condition. Training in these adverse conditions would also allow aircraft design engineers to better understand the effect of ineffective deicing equipment on the control of aircrafts. Pilot training flight simulators are readily available and are utilized. The available training programs are flexible and can be tailored to suit pilots’ needs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML