-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Game Theory

p-ISSN: 2325-0046 e-ISSN: 2325-0054

2019; 8(1): 9-15

doi:10.5923/j.jgt.20190801.02

Manufacturer’s Signaling Strategy in a Dual-channel Supply Chain

Zhao Rui-juan, Zhou Jian-heng

Glorious Sun School of Business & Management, Donghua University, Shanghai, China

Correspondence to: Zhao Rui-juan, Glorious Sun School of Business & Management, Donghua University, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated signaling strategy of a dual-channel supply chain, which contains a manufacturer (he), who owns a direct online channel and tries to convince his retailer (she) of the high-demand potential of his products, considering channel competition and free riding across channels. In this paper we incorporated retailer’s value-added services into the model, to analyze how the manufacturer uses wholesale price and slotting allowance to practice his signaling strategy under asymmetric information. Our results suggest that: compared with the situation when information is symmetric, under information asymmetry, the high-demand manufacturer needs to distort the wholesale price upward under some conditions, and pays lower slotting allowance to the retailer. However, in some situation, he can also realize separation by using the information-symmetry contract. Moreover, the fiercer of the competition is, or the greater the free-riding effect is, it is more possible that the manufacturer needs to choose the distorted wholesale price for signaling.

Keywords: Channel competition, Signaling, Dual-channel, Supply chain

Cite this paper: Zhao Rui-juan, Zhou Jian-heng, Manufacturer’s Signaling Strategy in a Dual-channel Supply Chain, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 9-15. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20190801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- With the rapid development of Internet technology, more and more manufacturers develop direct online channels on the basis of their traditional distribution channels, forming a dual-channel supply chain, such as IBM, Lenovo and so on. On one hand, direct online channels can help manufacturers to occupy the market more quickly. Moreover it is more easier for manufacturers to get more knowledge about their customers and cater to them. On the other hand, the direct channel of manufacturers will compete with the traditional channels in the terminal market. Therefore, the strategies of manufacturers and retailers are different in a dual-channel supply chain compared with that in a single-channel supply chain, especially when the two channels are opened online and offline. Offline store has more advantages of providing experienced service, compared with online store. However, customers can experience the product in an offline store and purchase online, which results in “free riding” (Zhou and Zhao 2016). To some extent, free riding may hurt the profits of offline store, which cause fiercer competition between two channels.Many researchers have discussed the necessity of opening direct online channel by manufacturers from the aspects of channel structure (Lu and Liu 2015, Wang et al. 2016, Li et al. 2016, Anil Arya 2010), pricing strategy (Lu and Liu 2013, Dan et al. 2012), revenue sharing (Lee et al. 2016, Kong et al. 2013) and so on. Most of these researches are carried out under the condition of full information. However, in the practice of supply chain, a dual-channel supply chain is more complex than a traditional single-channel supply chain, and the information between manufacturers and retailers is often asymmetric, which leads to a greater challenge to the coordination and management of supply chain. In reality, manufacturer is the producer and he will do relevant market research before production, so he has a better understanding of the actual situation of the product (such as quality, sales potential, etc.). However, because of information asymmetry, retailer may choose conservative ordering strategy since she doesn’t know the demand potential of products accurately. Conservative ordering strategy is unfavorable for the manufacturer with strong market demand (henceforth high-demand manufacturer). Therefore, in order to encourage the retailer to place orders optimistically, the high-demand manufacturer has incentive to send high-demand information to the retailer, which results in “signaling strategy” (Desai 2000).In the classical signaling strategy model, the player who conducts signaling needs to deviate from the optimal decision under full information and pay some rent. In the signaling model studied in this paper, the manufacturer realizes signaling strategy by providing the retailer with a third-level contract including wholesale price, slotting allowance and online price (Desai 2000, Li et al. 2014, Desai and Srinivasan 1995).This research mainly involves two aspects of researches: dual-channel supply chain and signaling strategy. For the research of dual-channel supply chain, current scholars focus mainly on the researches under information symmetry. For example, Lu and Liu (2015) studied the impact of the introduction of e-channels on the decisions and profits of manufacturers and retailers. They compared the signaling strategies in a single- and dual- supply chain (e-channel is independent from the retailer and the manufacturer), and found that the manufacturer can’t gain profit by introducing e-channel. Xiao et al. (2014) studied the impact of product diversity on channel structure. They set up a supply chain with a direct channel to sell customized products and a retail channel to sell standard products. Lu and Liu (2013) investigated two Stackelberg price game models and a Nash price game model, and found that channel acceptance has an important impact on equilibrium price. Their research showed that when a customer’s acceptance of a channel exceeds a certain threshold, this channel will dominate the whole system. Dan et al. (2012) analyzed the pricing problem of a centralized and decentralized dual-channel supply chain by using a two-stage Stackelberg game model, and evaluated the influence of retail services and customer loyalty on the pricing behavior of manufacturers and retailers.For the research of signaling strategy, the related research mainly appears in the economic research. However, the literatures of signaling strategy in a supply chain are very few, especially the signaling problem in a dual-channel supply chain. Desai and Srinivasan (1995) studied the signaling strategies between franchisees and their agents, considering the efforts of the agents. Based on this, Desai (2000) discussed the manufacturer uses advertising, slotting allowance and wholesale price as signal. The research showed that in the highly competitive retail market, manufacturers need to provide slotting allowance so that retailers can offset the cost of inventory costs. Li et al. (2014) investigated the retailer’s signaling strategy from the perspective of manufacturer intrusion. They assumed retailers have more private information and compared different signaling strategies when there is and isn’t manufacturer intrusion. It is found that retailers have no motivation to share information in a single-channel supply chain. On the contrary, when considering channel competition, retailers want to reduce competition by signaling to make manufacturers believe the market demand is small. However, this amplifies the effects of double marginalization and hurts the profits of both sides.These literatures are involved in the researches about dual-channel supply chain and signaling strategy, however, the research of signaling strategy of a dual-channel supply chain is still relatively small. Although the recent researches Desai (2000) and Li et al. (2014) discussed the problem of information asymmetry in the context of supply chain, our study is different from that. Desai (2000) studied the signaling strategy in a single-channel model, then extended the model to a dual-channel supply chain with two symmetrical entity terminals. However, we build a dual-channel supply chain which contains an online direct channel, taking retailers’ value-added services and free riding into consideration. Li et al. (2014) discussed the signaling strategy of the retailer, who has more information about customers. Based on the hypothesis that manufacturers have a better understanding of products and market demand, we investigate the signaling strategy of the manufacturer, who wants to induce the retailer to provide suitable services by signaling, especially when the online store can free ride the retailer’s services.

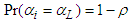

2. Model

- In this paper, we consider a two-level dual-channel supply chain model consisting of a manufacturer (he) with an online channel and a retailer (she). The manufacturer produces the product at marginal cost

(for simplicity, the cost is normalized to 0). He also needs to pay a certain slotting allowance

(for simplicity, the cost is normalized to 0). He also needs to pay a certain slotting allowance  to the retailer. Customers can choose to purchase from either the offline store or the online store. The retailer can promote the sale of the physical channel by providing some value-added services, such as experience service, with cost S. Due to the poor experience of online stores, we assume that they cannot provide experience services. However, online stores can “free ride” on the services of physical stores(Zhou and Zhao 2016), that is, consumers can experience products in physical stores (enjoy the service of physical retailers) and then purchase from online stores. We also assume that the product’s demand potential

to the retailer. Customers can choose to purchase from either the offline store or the online store. The retailer can promote the sale of the physical channel by providing some value-added services, such as experience service, with cost S. Due to the poor experience of online stores, we assume that they cannot provide experience services. However, online stores can “free ride” on the services of physical stores(Zhou and Zhao 2016), that is, consumers can experience products in physical stores (enjoy the service of physical retailers) and then purchase from online stores. We also assume that the product’s demand potential  contains two types: high demand type

contains two types: high demand type  and low demand type

and low demand type  , where

, where  ,

,  ,

,  . Since the manufacturer has a better understanding of the product’s performance, and he may also conduct market researches when developing product, so we assume that the manufacturer knows the product’s demand potential

. Since the manufacturer has a better understanding of the product’s performance, and he may also conduct market researches when developing product, so we assume that the manufacturer knows the product’s demand potential  exactly. However,

exactly. However,  is unknown to the retailer and she can only know the distribution of

is unknown to the retailer and she can only know the distribution of  , which satisfies

, which satisfies  ,

,  , and

, and  denotes the retailer’s belief in the product’s demand potential, where

denotes the retailer’s belief in the product’s demand potential, where  . When

. When  , it means that the retailer’s judgment of the product’s demand potential is consistent with the actual situation, and vice versa. Thus the demand potential is the manufacturer’s private information.Generally, the product’s demand potential can affect the retailer’s ordering decision. When the demand potential is high, the retailer is willing to make a higher order, and vice versa. Then, the demand potential affects the manufacturer’s sales volume and profit. Therefore, the manufacturer has incentive to disclose the information of product’s demand potential in the contract, that is, to carry out the signaling strategy (Desai 2000). Hence, in this paper, we consider the signaling strategy of a manufacturer in a dual-channel supply chain, in which the manufacturer opens a direct online channel, as shown in Figure 1.

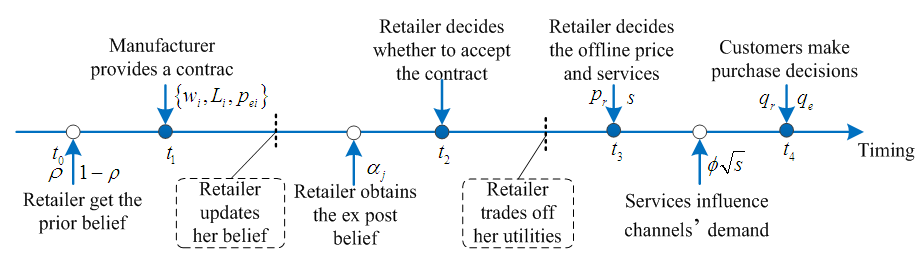

, it means that the retailer’s judgment of the product’s demand potential is consistent with the actual situation, and vice versa. Thus the demand potential is the manufacturer’s private information.Generally, the product’s demand potential can affect the retailer’s ordering decision. When the demand potential is high, the retailer is willing to make a higher order, and vice versa. Then, the demand potential affects the manufacturer’s sales volume and profit. Therefore, the manufacturer has incentive to disclose the information of product’s demand potential in the contract, that is, to carry out the signaling strategy (Desai 2000). Hence, in this paper, we consider the signaling strategy of a manufacturer in a dual-channel supply chain, in which the manufacturer opens a direct online channel, as shown in Figure 1. | Figure 1. Dual-channel signaling strategy model |

and

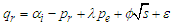

and  ) are affected by the type of demand potential

) are affected by the type of demand potential  , the price of the product, and the retailer’s value-added services.

, the price of the product, and the retailer’s value-added services.  and

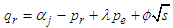

and  denote the price of the product sold in the offline store and online store, respectively. According to the setting of Desai (2000) and our assumption that the online store can free ride the experience service (value-added services) of the offline store, the demand of the offline store and the online store in this model is given by

denote the price of the product sold in the offline store and online store, respectively. According to the setting of Desai (2000) and our assumption that the online store can free ride the experience service (value-added services) of the offline store, the demand of the offline store and the online store in this model is given by  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.  is the additional demand brought by the experience services provided by the retailer, and

is the additional demand brought by the experience services provided by the retailer, and  is the exogenous random variable, which is assumed to

is the exogenous random variable, which is assumed to  .

.  represents the intensity of competition between the two channels, and the greater the

represents the intensity of competition between the two channels, and the greater the  , the fiercer the competition. As a result, the services of the retailer can increase the sales volume of the online store to some extent. However, the increase of the sales volume in the online store is smaller than that of the offline store. Therefore, we uses

, the fiercer the competition. As a result, the services of the retailer can increase the sales volume of the online store to some extent. However, the increase of the sales volume in the online store is smaller than that of the offline store. Therefore, we uses  to indicate the additional online demand increased by the retailer’s experience services, where

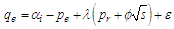

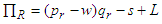

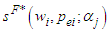

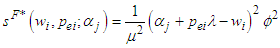

to indicate the additional online demand increased by the retailer’s experience services, where  . Thus the retailer’s and the manufacturer’s profit is given by

. Thus the retailer’s and the manufacturer’s profit is given by  and

and  , respectively. Both the manufacturer and the retailer are risk neutral and make decisions to maximize their own expected profits.Therefore, this paper studies how the manufacturer can make contract to transmit the signal of the product’s demand potential

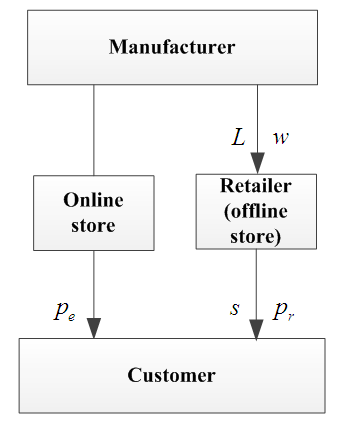

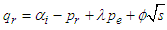

, respectively. Both the manufacturer and the retailer are risk neutral and make decisions to maximize their own expected profits.Therefore, this paper studies how the manufacturer can make contract to transmit the signal of the product’s demand potential  to the retailer, so as to achieve the separation equilibrium. According to the practice of supply chain management, this paper only focuses on the case of separation equilibrium.The sequence of this game is as follows: (1) at the beginning of the game, the retailer gets the prior belief about the type of the product’s demand potential (

to the retailer, so as to achieve the separation equilibrium. According to the practice of supply chain management, this paper only focuses on the case of separation equilibrium.The sequence of this game is as follows: (1) at the beginning of the game, the retailer gets the prior belief about the type of the product’s demand potential ( and

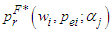

and  ); (2) the manufacturer offers the contract

); (2) the manufacturer offers the contract  to the retailer; (3) according to the contract offered by the manufacturer, the retailer updates her belief to

to the retailer; (3) according to the contract offered by the manufacturer, the retailer updates her belief to  and decides whether to accept the contract; (4) if she accepts the contract, the retailer needs to decide the offline price

and decides whether to accept the contract; (4) if she accepts the contract, the retailer needs to decide the offline price  and the value-added services

and the value-added services  according to the updated product’s demand potential

according to the updated product’s demand potential  and the online price

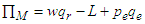

and the online price  ; (5) the demand is realized (see Figure 2).

; (5) the demand is realized (see Figure 2). | Figure 2. Timing of the game |

3. Benchmark (Symmetric Information)

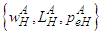

- We analyze the optimal decisions of the retailer and the manufacturer under symmetric information firstly in this section as benchmark case. The manufacturer provides a three-level contract

to the retailer. Under the condition of information symmetry, the product’s demand potential is the common knowledge of the manufacturer and the retailer. They know the value of

to the retailer. Under the condition of information symmetry, the product’s demand potential is the common knowledge of the manufacturer and the retailer. They know the value of  is

is  or

or  exactly, which means

exactly, which means  , where

, where  .In this paper, we use the upper corner

.In this paper, we use the upper corner  to denote the state of full information. Under full information, the manufacturer provides the retailer with a contract

to denote the state of full information. Under full information, the manufacturer provides the retailer with a contract  . We use backward induction to solve the game. According to the game sequence in Figure 2, we analyze the retailer’s decision firstly in the following subsection.

. We use backward induction to solve the game. According to the game sequence in Figure 2, we analyze the retailer’s decision firstly in the following subsection.3.1. The Decision of the Retailer

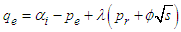

- According to the model setting, we can know that the demand of the offline store is

, and the demand of the online store is

, and the demand of the online store is  . The manufacturer makes the contract

. The manufacturer makes the contract  according to the real demand potential

according to the real demand potential  . The offline demand faced by the retailer when she makes decisions depends on her belief

. The offline demand faced by the retailer when she makes decisions depends on her belief  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  . The retailer’s profit is

. The retailer’s profit is  . She maximizes her profit to determine the optimal offline price

. She maximizes her profit to determine the optimal offline price  and the optimal value-added service

and the optimal value-added service  under full information, where

under full information, where

represents the optimal state,

represents the optimal state,  . Obviously, the retailer’s pricing and service decisions depend on her belief

. Obviously, the retailer’s pricing and service decisions depend on her belief  , and are influenced by the wholesale price

, and are influenced by the wholesale price  , which is decided by the manufacturer.

, which is decided by the manufacturer.3.2. The Decision of the Manufacturer

- According to the retailer’s decision, the actual offline demand is

| (1) |

,

,  into equation (1), we can obtain the demand of the offline store faced by the manufacturer:

into equation (1), we can obtain the demand of the offline store faced by the manufacturer: | (2) |

depends not only on the manufacturer’s belief

depends not only on the manufacturer’s belief  , but also on the retailer’s belief

, but also on the retailer’s belief  . When information is symmetric, the retailer’s judgment of the product’s demand potential is consistent with the actual situation, that is

. When information is symmetric, the retailer’s judgment of the product’s demand potential is consistent with the actual situation, that is  , where

, where  . Then we can rewrite

. Then we can rewrite  as

as  Similarly, we can derive the online demand faced by the manufacturer:

Similarly, we can derive the online demand faced by the manufacturer: In order to make sure

In order to make sure  , we have

, we have  and

and  . Moreover the conditions that

. Moreover the conditions that  and

and  , or

, or  and

and  should be satisfied. The retailer can rely on the fully visible market demand to make order, so the manufacturer can obtain a high order volume when demand potential is high type or a low order volume when demand potential is low type, that is

should be satisfied. The retailer can rely on the fully visible market demand to make order, so the manufacturer can obtain a high order volume when demand potential is high type or a low order volume when demand potential is low type, that is  . The contract offered by the manufacturer under full information is expressed by

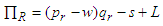

. The contract offered by the manufacturer under full information is expressed by  . The profit of the manufacturer

. The profit of the manufacturer  consists of two parts: the profit of the offline channel and the online channel. Thus, the profit maximization of the manufacturer

consists of two parts: the profit of the offline channel and the online channel. Thus, the profit maximization of the manufacturer  is solved as follows:

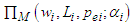

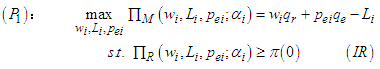

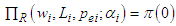

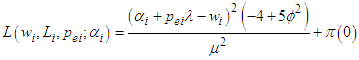

is solved as follows: where

where  is the retailer’s reservation utility, and

is the retailer’s reservation utility, and  is the retailer’s participation constraint. When the participation constraint is binding, i.e.,

is the retailer’s participation constraint. When the participation constraint is binding, i.e.,  , we can derive:

, we can derive: Thus, the problem

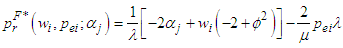

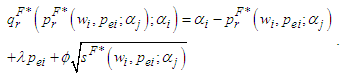

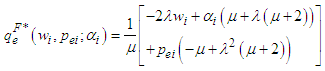

Thus, the problem  can be solved, and the optimal decision and profit of the manufacturer under full information can be obtained, see Proposition 1.Proposition 1 The optimal contract that the manufacturer offers to the retailer when information is symmetric is given by

can be solved, and the optimal decision and profit of the manufacturer under full information can be obtained, see Proposition 1.Proposition 1 The optimal contract that the manufacturer offers to the retailer when information is symmetric is given by  , and his optimal profit is

, and his optimal profit is  , where:

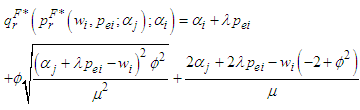

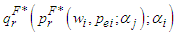

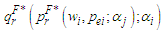

, where:

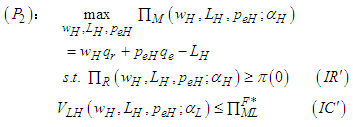

4. Signaling Strategy of the Manufacturer

- In Section 3, the decisions under full information of the manufacturer and the retailer are analyzed. The retailer can obtain reservation utility only when information is symmetric. Under information asymmetry, the product’s demand potential

is the manufacturer’s private information. Therefore, the low-demand manufacturer has incentive to announce high demand so as to obtain a higher order. From the view of the retailer, she may make conservative ordering decision to avoid being deceived by the low-demand manufacturer. All these behaviors may hurt the interests of the high-demand manufacturer. When a high-demand manufacturer offers a contract

is the manufacturer’s private information. Therefore, the low-demand manufacturer has incentive to announce high demand so as to obtain a higher order. From the view of the retailer, she may make conservative ordering decision to avoid being deceived by the low-demand manufacturer. All these behaviors may hurt the interests of the high-demand manufacturer. When a high-demand manufacturer offers a contract  , where the superscript

, where the superscript  represents the state of information asymmetry, the low-demand manufacturer has incentive to make a high-type contract, too. If the retailer believes the product of the low-demand manufacturer has high demand, she updates her belief to

represents the state of information asymmetry, the low-demand manufacturer has incentive to make a high-type contract, too. If the retailer believes the product of the low-demand manufacturer has high demand, she updates her belief to  , and sets

, and sets  and

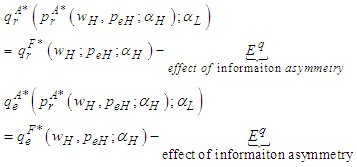

and  as the optimal offline price and the value-added service corresponding to the high-demand product. However, the actual demand potential is low type. Thus the actual offline and online demands under information asymmetry are given in Proposition 2.Proposition 2 Under information asymmetry, the actual demands of the offline and online store realized by the low-demnad manufacturer who disguises as high-demand manufacturer are as follows:

as the optimal offline price and the value-added service corresponding to the high-demand product. However, the actual demand potential is low type. Thus the actual offline and online demands under information asymmetry are given in Proposition 2.Proposition 2 Under information asymmetry, the actual demands of the offline and online store realized by the low-demnad manufacturer who disguises as high-demand manufacturer are as follows: where

where  .

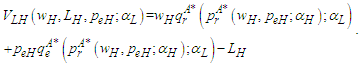

. denotes the “information-asymmetry effect” factor of the channel demand, which indicates the influence of information-asymmetry effect on sales volume. Proposition 2 shows that the camouflage behavior of the low-demand manufacturer reduces the sales volume in both channels compared with the volume when information is symmetric.

denotes the “information-asymmetry effect” factor of the channel demand, which indicates the influence of information-asymmetry effect on sales volume. Proposition 2 shows that the camouflage behavior of the low-demand manufacturer reduces the sales volume in both channels compared with the volume when information is symmetric.  denotes the manufacturer’s profit when the real demand potential is

denotes the manufacturer’s profit when the real demand potential is  but the manufacturer discloses it as

but the manufacturer discloses it as  . Therefore, under information asymmetry, the profit of the low-demand manufacturer who chooses the high-type contract can be written as follows:

. Therefore, under information asymmetry, the profit of the low-demand manufacturer who chooses the high-type contract can be written as follows: In order to achieve signaling, the high-demand manufacturer maximizes his profit to make decision:

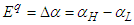

In order to achieve signaling, the high-demand manufacturer maximizes his profit to make decision:

is the participation constraint of the retailer and

is the participation constraint of the retailer and  is the incentive constraint of the manufacturer.

is the incentive constraint of the manufacturer.  is the profit of the low-demand manufacturer when he selects the low-type contract, which is also the low-demand manufacturer’s profit under full information. In this situation, if and only if the profit that the low-demand manufacturer earns by selecting

is the profit of the low-demand manufacturer when he selects the low-type contract, which is also the low-demand manufacturer’s profit under full information. In this situation, if and only if the profit that the low-demand manufacturer earns by selecting  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) is less than the profit that he can get when he reveals information truthfully (i.e.,

) is less than the profit that he can get when he reveals information truthfully (i.e.,  ), the high-demand manufacturer can be separated successfully from the low-demand manufacturer.It is worth noting that when

), the high-demand manufacturer can be separated successfully from the low-demand manufacturer.It is worth noting that when  satisfies certain conditions, even if the high-demand manufacturer still chooses the information-symmetry contract

satisfies certain conditions, even if the high-demand manufacturer still chooses the information-symmetry contract  as his optimal strategy under information asymmetry, he can also be separated from the low-demand manufacturer. Therefore, for signaling successfully, the profit that the low-demand manufacturer earns when choosing

as his optimal strategy under information asymmetry, he can also be separated from the low-demand manufacturer. Therefore, for signaling successfully, the profit that the low-demand manufacturer earns when choosing  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) should not exceed the profit when he is not camouflaged (i.e.,

) should not exceed the profit when he is not camouflaged (i.e.,  ). In other words, the following condition should be satisfied:

). In other words, the following condition should be satisfied: Then the low-demand manufacturer has no motive to camouflage, and the high-demand manufacturer can realize separation by the pricing strategy under full information. On the contrary, he needs to adjust the optimal strategy and use the contract

Then the low-demand manufacturer has no motive to camouflage, and the high-demand manufacturer can realize separation by the pricing strategy under full information. On the contrary, he needs to adjust the optimal strategy and use the contract  . By solving the problem

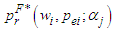

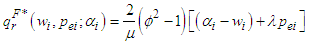

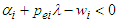

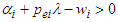

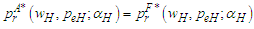

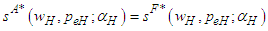

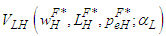

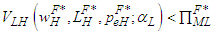

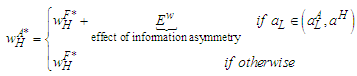

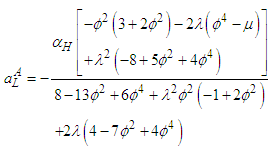

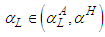

. By solving the problem  , we can obtain the signaling strategy of the manufacturer under information asymmetry, as shown in Proposition 3.Proposition 3 When information is asymmetric, if and only if

, we can obtain the signaling strategy of the manufacturer under information asymmetry, as shown in Proposition 3.Proposition 3 When information is asymmetric, if and only if  , the high-demand manufacturer will choose higher wholesale and online pricing strategy to realize signaling; otherwise, by choosing the wholesale price

, the high-demand manufacturer will choose higher wholesale and online pricing strategy to realize signaling; otherwise, by choosing the wholesale price  and the online price

and the online price  under full information he can be separated from the low-demand manufacturer naturally. That is:

under full information he can be separated from the low-demand manufacturer naturally. That is: where

where We define

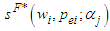

We define  . According to Proposition 3, it can be found that when

. According to Proposition 3, it can be found that when  , the high-demand manufacturer will choose

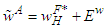

, the high-demand manufacturer will choose  as his optimal wholesale pricing strategy. Similar with Proposition 2,

as his optimal wholesale pricing strategy. Similar with Proposition 2,  contains a factor

contains a factor  1, which indicates the influence of information-asymmetry effect on wholesale price. Since

1, which indicates the influence of information-asymmetry effect on wholesale price. Since  is greater than zero, information asymmetry has a positive impact on the wholesale price pricing strategy of the manufacturer.Therefore, when

is greater than zero, information asymmetry has a positive impact on the wholesale price pricing strategy of the manufacturer.Therefore, when  , the high-demand manufacturer has to distort the wholesale price upward to realize signaling in a dual-channel supply chain, and pay lower slotting allowance to the retailer (i.e.,

, the high-demand manufacturer has to distort the wholesale price upward to realize signaling in a dual-channel supply chain, and pay lower slotting allowance to the retailer (i.e.,  Otherwise, he can also realize natural separation by adopting the pricing decisions of information symmetry.Besides the wholesale price, the online price is also transmitted to the retailer as a “high type” signal. When the retailer observes that the manufacturer is setting high prices in his online store, she will consider him as a high-demand type. When the product demand potential is high, on one hand, the manufacturer needs to set higher price to transmit the information to the retailer that his product is “good”; on the other hand, he can ask for a higher wholesale price and a lower slotting allowance because of his “good” product. Therefore, the manufacturer has more bargaining power to set a higher wholesale price and online price if his product’s demand potential is high enough. This is true in practice. Normally, customers will consider a product is better when its price is higher, and sellers always use higher price to differ their products from others. Hence, manufacturers should try to produce the products with high demand potential to get more bargaining power.Moreover, the intensity of competition between the two channels

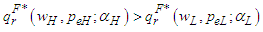

Otherwise, he can also realize natural separation by adopting the pricing decisions of information symmetry.Besides the wholesale price, the online price is also transmitted to the retailer as a “high type” signal. When the retailer observes that the manufacturer is setting high prices in his online store, she will consider him as a high-demand type. When the product demand potential is high, on one hand, the manufacturer needs to set higher price to transmit the information to the retailer that his product is “good”; on the other hand, he can ask for a higher wholesale price and a lower slotting allowance because of his “good” product. Therefore, the manufacturer has more bargaining power to set a higher wholesale price and online price if his product’s demand potential is high enough. This is true in practice. Normally, customers will consider a product is better when its price is higher, and sellers always use higher price to differ their products from others. Hence, manufacturers should try to produce the products with high demand potential to get more bargaining power.Moreover, the intensity of competition between the two channels  can affect the high-demand manufacturer’s signaling strategy, see Proposition 4.Proposition 4 The fiercer the competition, the greater the likelihood of the distortion of the wholesale price, i.e.,

can affect the high-demand manufacturer’s signaling strategy, see Proposition 4.Proposition 4 The fiercer the competition, the greater the likelihood of the distortion of the wholesale price, i.e.,  .The more intense the competition between channels, i.e., the larger

.The more intense the competition between channels, i.e., the larger  , the smaller

, the smaller  . In other word, the area

. In other word, the area  in which the manufacturer sets

in which the manufacturer sets  as the optimal wholesale price becomes larger with the increasing of

as the optimal wholesale price becomes larger with the increasing of  . Thus, it is more possible that the wholesale price will be distorted upward. When competition between channels increases, channel demand is more sensitive to the price of the competitive channel and the services provided by the retailer. In particular, when the retailer provide services that costs

. Thus, it is more possible that the wholesale price will be distorted upward. When competition between channels increases, channel demand is more sensitive to the price of the competitive channel and the services provided by the retailer. In particular, when the retailer provide services that costs  , the demand of the online channel can increase

, the demand of the online channel can increase  due to free riding. So the larger

due to free riding. So the larger  , the stronger the free-riding effect, the more that the manufacturer can benefit from it. In this situation, the manufacturer has more inventiveness to send the high-demand type signal to the retailer by distorting wholesale price upwards, so as to encourage the retailer to provide suitable services for the products. Therefore, channel competition is good for the manufacturer, especially when cross-channel free riding exists in the supply chain. This is one aspect to explain why more and more manufacturers open online channels now. This also suggests that manufacturers can bring more competition factors into supply chain, build a supply chain with multiple-channel types, and take good use of the different abilities of different channels, so as to get more benefit.

, the stronger the free-riding effect, the more that the manufacturer can benefit from it. In this situation, the manufacturer has more inventiveness to send the high-demand type signal to the retailer by distorting wholesale price upwards, so as to encourage the retailer to provide suitable services for the products. Therefore, channel competition is good for the manufacturer, especially when cross-channel free riding exists in the supply chain. This is one aspect to explain why more and more manufacturers open online channels now. This also suggests that manufacturers can bring more competition factors into supply chain, build a supply chain with multiple-channel types, and take good use of the different abilities of different channels, so as to get more benefit.5. Conclusions

- In this paper, we investigate the signaling strategy of the manufacturer who owns an online direct channel in a dual-channel supply chain, considering the online store can free ride the offline services (i.e., experienced services) provided by the retailer. We analyze and compare the strategies of the manufacturer under two conditions: symmetric information and asymmetric information, to show how the demand of two channels and the manufacturer’s contract differ in these two situations. We also discuss the impact of channel competition and free riding on the manufacturer’s signaling strategy. We find that: when information is asymmetric, the demand of both channels decline compared with that when information is symmetric, and the high-demand manufacturer needs to distort the wholesale price upward under some conditions to practice signaling strategy; however, when the product’s demand potential satisfies some conditions, he can also realize separation by using the information-symmetry contract; moreover, the fiercer the competition is, or the greater the free-riding effect is, it is more possible that the manufacturer needs to choose the distorted wholesale price for signaling. Our research suggests that manufacturers can try to produce better products with higher demand potential to get more bargaining power, i.e., setting higher wholesale price, pay less slotting allowance, getting more value-added services, etc. High-demand manufactures can be separated from low-demand ones by using higher pricing strategies. Manufacturers should also bring competition factors into supply chain by building a multiple-channel type supply chain, for example, opening online direct channels, and take good use of channel competition and cross-channel free riding.This study supplements the theoretical basis and practical inspiration for manufacturers to deal with signaling problems in a dual-channel supply chain, taking channel competition, retailer services, free riding and other factors into consideration, so that the supply chain signaling research is more abundant. Without losing generality, we can relax the assumption that retailers retain the same utility in different states (cooperating with high-demand and low-demand manufacturers) in further research.

Note

- 1. For simplicity, we don’t give the expression of

here. It can be derived by solving

here. It can be derived by solving  .

. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML