Qing Hu1, 2

1Department of Economics, Kushiro Public University of Economics, Kushiro, Japan

2Research Fellow, Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan

Correspondence to: Qing Hu, Department of Economics, Kushiro Public University of Economics, Kushiro, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

We consider a firm which sells one product in a monopolistic market and sells another product in an oligopolistic market. The leverage theory states that bundling the two products is always profitable. We investigate whether the leverage theory still holds in network industries. We find that this conventional wisdom reverses and bundling is not always preferred. In addition, we find that the profitable bundling can increase the consumer surplus when the network effect is relatively intense.

Keywords:

Network externality, Bundling, Cournot duopoly

Cite this paper: Qing Hu, Network Externalities and Bundling, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2018, pp. 23-26. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20180702.01.

1. Introduction

It is commonplace to see bundling-selling several products in a single package. In the leverage theory, if the firm bundles one product sold in a monopolistic market and another product sold in an oligopolistic market, the firm obtains larger market powerin the latter. Many previous researches show that in such market structure, a firm may have an incentive to bundle (Carbajo et al., 1990; Martin, 1999, Chung et al., 2013). Carbajo et al. (1990) first pointed that a commitment of bundling decreases the outputs of the rival’s, and this is the reason that bundling is profitable under Cournot competition when the cost of all products is same. And bundling decreases the consumer surplus and social welfare. Such bundling has been always suspected as a tool to exclude rivals and harm competition. For example, in Japan, Microsoft monopolizes the spreadsheet market (Excel) but competes with Ichitaro in the word processor market. Japan Fair Trade Commission recommended ceasing this Microsoft’s bundling of Word and Excel because this bundling is suspected as a behavior to exclude Ichitaro. However, we can find that the softwares are network products-the utility derived by a consumer of the product increases with the number of other consumers of that product. As the fast development of network industries in recent years, there are many researches about how network externalities change the results under standard normal product market (Katz and Shapiro, 1985; Pal, 2014; Fanti and Buccella, 2016; Pal and Scrimitore 2016). We intend to investigate whether the above conventional wisdom that bundling is always profitable still holds in network industries. There is a lack of such analysis about bundling incentive in network industries and we aim at filling this gap. We reexamine the results of Carbajo et al. (1990) under Cournot competition by considering network effect. We find that the conventional reverses and bundling is not always preferred. This results are very meaningful for firms to investigate the rationale to operate bundling in network industries. Meanwhile, when the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. This suggests that not all bundling decreases the consumer surplus and this result opens a new perspective to judge the legal use of bundling. The reminder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the model and results. Section 3 concludes the study. 2.

2. The Model and Results

The model set up builds on Carbajo et al. (1990). Suppose there are two network products, product A and product B. Product A is solely produced by firm 1 while product B is produced by firm 1 and firm 2. We assume that the marginal cost of either product for both firms is zero. When firm 1 sells own products, the firm can bundle them. When firm 1 does not bundle its products, the firm freely chooses  and

and  for the sales of products product A and product B, respectively; firm 2 chooses

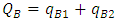

for the sales of products product A and product B, respectively; firm 2 chooses  for the sales of product B. Thus, the aggregate sales of products A and B are

for the sales of product B. Thus, the aggregate sales of products A and B are  and

and  , respectively. On the other hand, when firm 1 decides to bundle, the firm chooses the sales of bundle

, respectively. On the other hand, when firm 1 decides to bundle, the firm chooses the sales of bundle  ; firm 2 sets its sales

; firm 2 sets its sales  . Therefore, the aggregate sales are

. Therefore, the aggregate sales are  and

and  . For simplicity, we assume that the two products are independent. We analyze the following of the game. At stage 1, firm 1 decides whether to bundle. At stage 2, firms compete in quantities. The game is solved using backward induction.

. For simplicity, we assume that the two products are independent. We analyze the following of the game. At stage 1, firm 1 decides whether to bundle. At stage 2, firms compete in quantities. The game is solved using backward induction.

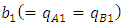

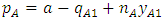

2.1. Case without Bundling

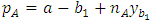

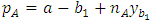

Under the case without bundling, the inverse demand function of product A and product B are  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.  and

and  denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.  denote the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of product A and product B, respectively.  is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 2’s sales of product B. The parameter

is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 2’s sales of product B. The parameter  and

and  measures the strength of network effects in the markets-lower value

measures the strength of network effects in the markets-lower value  indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),

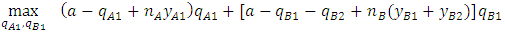

indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),  is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 chooses

is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 chooses  and

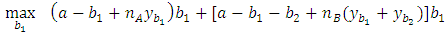

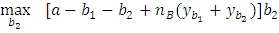

and  to maximize the total profits

to maximize the total profits  :

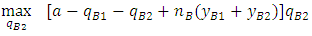

: firm 2 chooses

firm 2 chooses  and maximizes

and maximizes  :

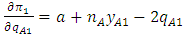

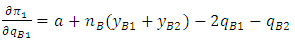

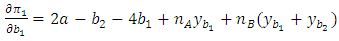

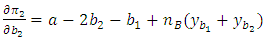

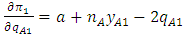

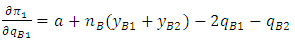

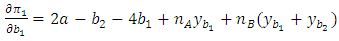

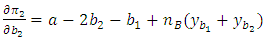

:  Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

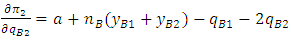

Then we get the quantity reaction functions:  | (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

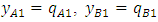

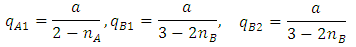

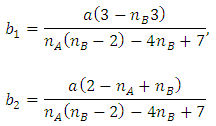

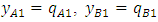

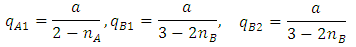

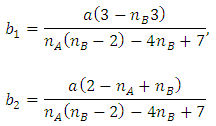

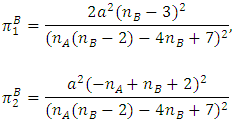

We solve (1) (2) (3) for the Nash equilibrium satisfying the rational expectations condition that  and

and  , then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

, then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:  | (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

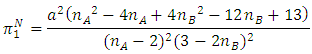

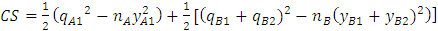

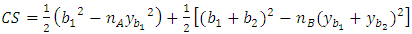

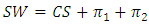

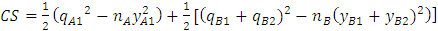

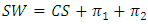

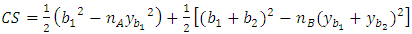

Consumer surplus is given as  . Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (4), we have:

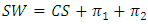

. When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (4), we have:  | (7) |

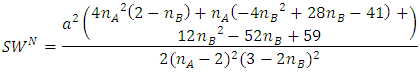

| (8) |

where the superscript N recalls that it is obtained without bundling.

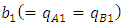

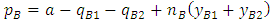

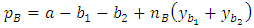

2.2. Case with Bundling

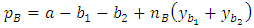

Under the case with bundling, the inverse demand function of product A and product B are  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.  and

and  denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.  denotes the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of the bundle of product A and product B.

denotes the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of the bundle of product A and product B.  is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm B’s sales of product 2. The parameter

is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm B’s sales of product 2. The parameter  and

and  measures the strength of network effects-lower value

measures the strength of network effects-lower value  indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),

indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),  is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 sets

is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 sets  to maximize the total profits

to maximize the total profits  :

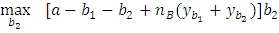

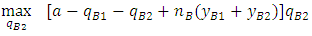

:  firm 2 sets

firm 2 sets  to maximize

to maximize  :

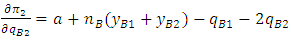

:  Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

Then we get the quantity reaction functions:  | (8) |

| (9) |

Solving the best reaction functions in (8) (9) together with  and

and  , then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

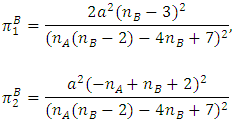

, then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:  | (10) |

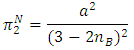

| (11) |

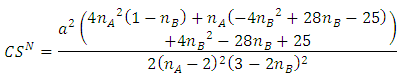

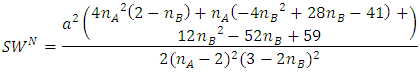

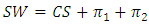

Consumer surplus is given as  . Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (10), we have:

. When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (10), we have:  | (12) |

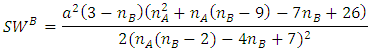

| (13) |

where the superscript B recalls that it is obtained with bundling.

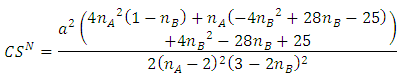

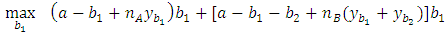

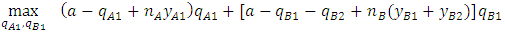

2.3. Comparison

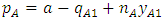

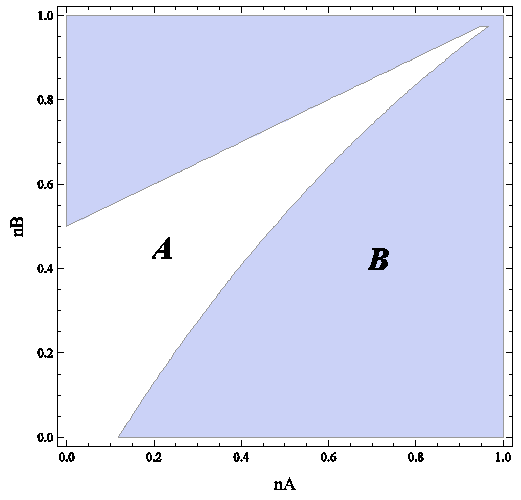

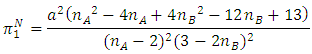

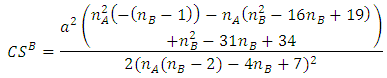

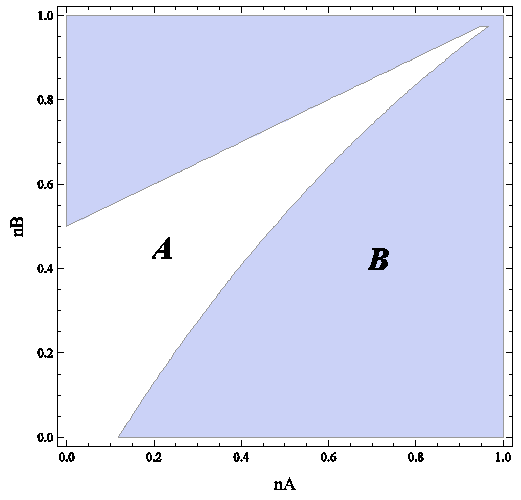

Here, we compare the outcomes with and without bundling. First, comparing the equilibrium profits of firm 1, we get following: Proposition 1. In the presence of network externalities, profits of firm 1 under the case without bundling may be higher than those under bundling. The conventional wisdom that bundling always dominates not bundling reverses.  | Figure 1.  in region A; in region A;  in the shadow region B in the shadow region B |

Proof: Proposition 1 is provided by Figure 1 considering that:  applies in region A;

applies in region A;  applies in region B. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that firm 1 always prefers bundling (

applies in region B. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that firm 1 always prefers bundling ( at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects. The intuition behind our results is as follows. When a firm bundles its products, equilibrium sales in the monopoly market must be different from that before bundling. Therefore, the bundling firm loses a part of the profit in the monopoly market. To gain profit, bundling makes the firm to raise production of the bundle and behave more aggressive in the duopoly market. A commitment of aggressive behaviour by the bundling firm reduces the rival’s sales. And this response by the rival firm makes bundling profitable. Compared with the case without bundling, bundling makes the duopoly market more aggressive and reduces the output level of the monopoly market. The above is stated in Carbajo et al. (1990), without considering the network effect. However, as the network effect is stronger, it brings the more aggressive play more profits via consumers’ expectations. As the network effect of the duopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the bundling firm; However, as the network effect of the monopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the multiproduct firm without bundling. And the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market dominates that in the duopoly market. Therefore, When the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market without bundling is stronger than the positive effect from network effect and the benefit for the sales reduction of the rival under bundling in the duopoly market, not bundling is more preferred. From Figure 1, we can find that not bundling is more likely to happen. We note here that

at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects. The intuition behind our results is as follows. When a firm bundles its products, equilibrium sales in the monopoly market must be different from that before bundling. Therefore, the bundling firm loses a part of the profit in the monopoly market. To gain profit, bundling makes the firm to raise production of the bundle and behave more aggressive in the duopoly market. A commitment of aggressive behaviour by the bundling firm reduces the rival’s sales. And this response by the rival firm makes bundling profitable. Compared with the case without bundling, bundling makes the duopoly market more aggressive and reduces the output level of the monopoly market. The above is stated in Carbajo et al. (1990), without considering the network effect. However, as the network effect is stronger, it brings the more aggressive play more profits via consumers’ expectations. As the network effect of the duopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the bundling firm; However, as the network effect of the monopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the multiproduct firm without bundling. And the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market dominates that in the duopoly market. Therefore, When the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market without bundling is stronger than the positive effect from network effect and the benefit for the sales reduction of the rival under bundling in the duopoly market, not bundling is more preferred. From Figure 1, we can find that not bundling is more likely to happen. We note here that  always. Next, we compare the equilibrium consumer surplus. Proposition 2. When the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling may increase the consumer surplus. The conventional wisdom that profitable bundling always decreases the consumer surplus reverses.

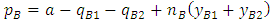

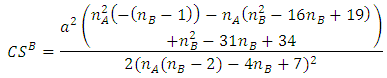

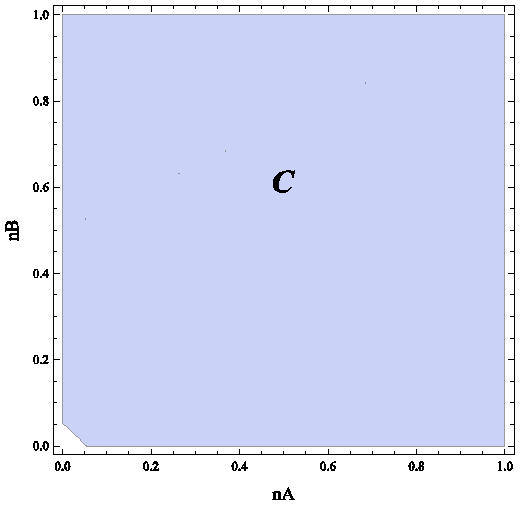

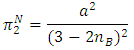

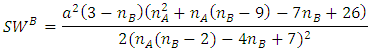

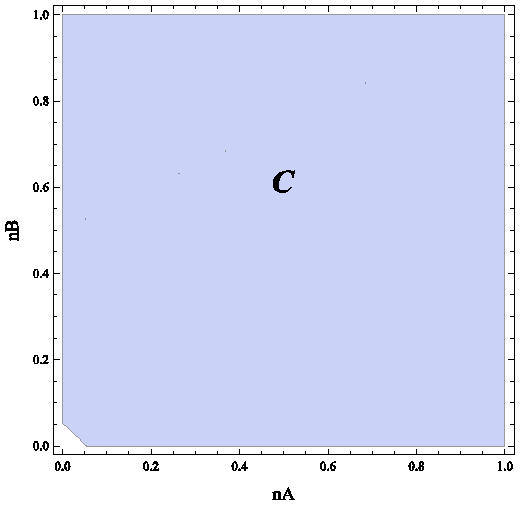

always. Next, we compare the equilibrium consumer surplus. Proposition 2. When the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling may increase the consumer surplus. The conventional wisdom that profitable bundling always decreases the consumer surplus reverses.  | Figure 2.  in region C in region C |

Proof: Proposition 2 is provided by Figure 2 considering that:  applies in region C, otherwise the reverse is true. We can find that part of region A in Figure 1 duplicates with region C and indicates that the profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that bundling always decreases the consumer surplus (

applies in region C, otherwise the reverse is true. We can find that part of region A in Figure 1 duplicates with region C and indicates that the profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that bundling always decreases the consumer surplus ( at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects.

at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects.

3. Conclusions

This paper investigates whether the conventional wisdom that bundling is always profitable still holds in network industries. We find that the conventional wisdom reverses and bundling is not always preferred. Our results are very meaningful for firms to examine the rationale to operate bundling in network industries. Meanwhile, when the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. This suggests that not all bundling decreases the consumer surplus and this result opens a new perspective to judge the legal use of bundling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to Prof. Mizuno Tomomichi, graduate school of Kobe university, and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions that have substantially improved the quality of the paper.

References

| [1] | Carbajo, J., De Meza, D., and Seidmann, D.J. (1990). A strategic motivation for commodity bundling. Journal of Economics, 38, 283-298. |

| [2] | Chung, H.L., Lin, Y.S., and Hu, J.L. (2013). Bundling strategy and product differentiation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 108, 207-229. |

| [3] | Fanti, L. and D. Buccella (2016). Network externalities and corporate social responsibility. Economics Bulletin, 36, 2043–2050. |

| [4] | Katz, M. and C. Shapiro. (1985). Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. American Economic Review, 34, 424-440. |

| [5] | Martin, S. (1999). Strategic and welfare implications of bundling. Economics Letters, 62, 371-376. |

| [6] | Pal, R. (2014). Price and quantity competition in network gods duopoly: a reversal result. Economics Bulletin, 75, 1019-1027. |

| [7] | Pal, R. and Scrimitore, M. (2016). Tacit collusion and market concentration under network effects. Economics Letters, 145, 266-269. |

| [8] | Peitz, M. (2008). Bundling may blockade entry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26 (1), 41-58. |

and

and  for the sales of products product A and product B, respectively; firm 2 chooses

for the sales of products product A and product B, respectively; firm 2 chooses  for the sales of product B. Thus, the aggregate sales of products A and B are

for the sales of product B. Thus, the aggregate sales of products A and B are  and

and  , respectively. On the other hand, when firm 1 decides to bundle, the firm chooses the sales of bundle

, respectively. On the other hand, when firm 1 decides to bundle, the firm chooses the sales of bundle  ; firm 2 sets its sales

; firm 2 sets its sales  . Therefore, the aggregate sales are

. Therefore, the aggregate sales are  and

and  . For simplicity, we assume that the two products are independent. We analyze the following of the game. At stage 1, firm 1 decides whether to bundle. At stage 2, firms compete in quantities. The game is solved using backward induction.

. For simplicity, we assume that the two products are independent. We analyze the following of the game. At stage 1, firm 1 decides whether to bundle. At stage 2, firms compete in quantities. The game is solved using backward induction.  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.  and

and  denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.  denote the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of product A and product B, respectively.  is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 2’s sales of product B. The parameter

is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 2’s sales of product B. The parameter  and

and  measures the strength of network effects in the markets-lower value

measures the strength of network effects in the markets-lower value  indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),

indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),  is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 chooses

is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 chooses  and

and  to maximize the total profits

to maximize the total profits  :

: firm 2 chooses

firm 2 chooses  and maximizes

and maximizes  :

:  Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

and

and  , then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

, then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

. Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (4), we have:

. When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (4), we have:

and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.  and

and  denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.

denote the price of product A and product B, respectively.  denotes the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of the bundle of product A and product B.

denotes the consumers’ expectation regarding firm 1’s sales of the bundle of product A and product B.  is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm B’s sales of product 2. The parameter

is the consumers’ expectation regarding firm B’s sales of product 2. The parameter  and

and  measures the strength of network effects-lower value

measures the strength of network effects-lower value  indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),

indicates weaker network externalities. Following Carbajo et al. (1990),  is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 sets

is a demand parameter for both markets. At stage 2, firm 1 sets  to maximize the total profits

to maximize the total profits  :

:  firm 2 sets

firm 2 sets  to maximize

to maximize  :

:  Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

Then we get the quantity reaction functions:

and

and  , then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

, then we have the equilibrium quantities and profits as following:

. Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (10), we have:

. When rational expectation realize, by substituting of (10), we have:

in region A;

in region A;  in the shadow region B

in the shadow region B applies in region A;

applies in region A;  applies in region B. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that firm 1 always prefers bundling (

applies in region B. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that firm 1 always prefers bundling ( at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects. The intuition behind our results is as follows. When a firm bundles its products, equilibrium sales in the monopoly market must be different from that before bundling. Therefore, the bundling firm loses a part of the profit in the monopoly market. To gain profit, bundling makes the firm to raise production of the bundle and behave more aggressive in the duopoly market. A commitment of aggressive behaviour by the bundling firm reduces the rival’s sales. And this response by the rival firm makes bundling profitable. Compared with the case without bundling, bundling makes the duopoly market more aggressive and reduces the output level of the monopoly market. The above is stated in Carbajo et al. (1990), without considering the network effect. However, as the network effect is stronger, it brings the more aggressive play more profits via consumers’ expectations. As the network effect of the duopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the bundling firm; However, as the network effect of the monopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the multiproduct firm without bundling. And the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market dominates that in the duopoly market. Therefore, When the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market without bundling is stronger than the positive effect from network effect and the benefit for the sales reduction of the rival under bundling in the duopoly market, not bundling is more preferred. From Figure 1, we can find that not bundling is more likely to happen. We note here that

at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects. The intuition behind our results is as follows. When a firm bundles its products, equilibrium sales in the monopoly market must be different from that before bundling. Therefore, the bundling firm loses a part of the profit in the monopoly market. To gain profit, bundling makes the firm to raise production of the bundle and behave more aggressive in the duopoly market. A commitment of aggressive behaviour by the bundling firm reduces the rival’s sales. And this response by the rival firm makes bundling profitable. Compared with the case without bundling, bundling makes the duopoly market more aggressive and reduces the output level of the monopoly market. The above is stated in Carbajo et al. (1990), without considering the network effect. However, as the network effect is stronger, it brings the more aggressive play more profits via consumers’ expectations. As the network effect of the duopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the bundling firm; However, as the network effect of the monopoly market increases, it brings more positive effect to the multiproduct firm without bundling. And the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market dominates that in the duopoly market. Therefore, When the positive effect from network effect in the monopoly market without bundling is stronger than the positive effect from network effect and the benefit for the sales reduction of the rival under bundling in the duopoly market, not bundling is more preferred. From Figure 1, we can find that not bundling is more likely to happen. We note here that  always. Next, we compare the equilibrium consumer surplus. Proposition 2. When the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling may increase the consumer surplus. The conventional wisdom that profitable bundling always decreases the consumer surplus reverses.

always. Next, we compare the equilibrium consumer surplus. Proposition 2. When the network effect is relatively intense, profitable bundling may increase the consumer surplus. The conventional wisdom that profitable bundling always decreases the consumer surplus reverses.

in region C

in region C applies in region C, otherwise the reverse is true. We can find that part of region A in Figure 1 duplicates with region C and indicates that the profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that bundling always decreases the consumer surplus (

applies in region C, otherwise the reverse is true. We can find that part of region A in Figure 1 duplicates with region C and indicates that the profitable bundling increases the consumer surplus. Compared with Carbajo et al. (1990)’s results which show that bundling always decreases the consumer surplus ( at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects.

at the origin point (0,0)), our paper shows different results by considering network effects.  Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML