-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Game Theory

p-ISSN: 2325-0046 e-ISSN: 2325-0054

2018; 7(1): 7-16

doi:10.5923/j.jgt.20180701.02

Indirect Taxation and Privatization in a Model of Government’s Tax Preference

1Graduate School of International Studies, Pusan National University, Busan, Korea

2College of Business Administration, Inha University, Incheon, Korea

Correspondence to: Min Hwan Lee, College of Business Administration, Inha University, Incheon, Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

By introducing government preferences for tax revenues into a unionized mixed duopoly, this study investigates how such preferences can change a government’s choice of indirect tax regimes between ad valorem and specific taxes. The main results are as follows. Given that one of the tax regimes is predetermined, privatization never improves welfare and is preferable for the government when the preference of tax revenue is high. However, when the tax regime is endogenously determined by the government, privatization is preferable from the viewpoint of social welfare if the government heavily emphasizes tax revenue. Thus, there are conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government: If it heavily emphasizes tax revenue, then the government always has an incentive to levy specific tax, while the public firm has an incentive to be levied ad valorem tax. However, there are no conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government when the government levies specific tax, even though it places less emphasis on tax revenue” or “when the government levies specific tax, but the preference for tax revenue is sufficiently when the government levies specific tax, even though it places less emphasis on tax revenue Interestingly, the government never has an incentive for privatization when considering either tax as an option.

Keywords: Ad Valorem Tax, Specific Tax, Government’s Payoff, Social Welfare, Privatization

Cite this paper: Kangsik Choi, Min Hwan Lee, Indirect Taxation and Privatization in a Model of Government’s Tax Preference, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 7-16. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20180701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is well known that ad valorem taxes dominate specific taxes from the welfare perspective as evidenced by Seade (1985) and Delipalla and Keen (1992), among others (see also Keen’s (1998) comprehensive survey paper). Surprisingly, in the literature on mixed oligopoly, there have been few analyses of socially optimal taxation that weigh the advantages of ad valorem and specific taxes. Mujumdar and Pal (1998) exceptionally showed that privatization could increase both social welfare and tax revenues, and that an increase in tax does not change the total output but increases the output of the public firm and tax revenues.As stated above, concerning private firms, canonical arguments on the comparison of ad valorem and specific taxes implicitly assume that the government’s (or social planner’s) objective is to maximize social welfare. On the other hand, the public firm’s welfare-maximizing behavior is assumed to support the objective of benevolent government. Thus, it is generally understood that the public firm, as well as the government, traditionally maximizes the sum of tax revenues or subsidies and the consumer and producer surpluses. However, in the real world, some conflicts of interest exist between the public firm in an industry and the government. For example, Vickers and Yarrow (1988, p. 128) argue that “Ministers were left to free to adopt their own definition of the public interest…, and there have been frequent political interventions to influence operational decision making.” In this regard, other views on the objective of the government exist in the literature, including that the government maximizes tax revenue for its own private agenda or that it is intrinsically a tax-revenue maximizer (e.g., Besley, 2006; Brennan and Buchanan, 1980; Niskanen, 1971). It is often argued that the political structure of a country plays a role in determining the government’s objective function. Edwards and Keen (1996) and Wilson (2005) argued that a Leviathan government tends to maximize its net tax revenue to increase government size so that more revenue is at the government’s disposal. A number of empirical studies also provide evidence in support of tax revenue maximization by the government (see Caplan, 2001; Zax, 1989; Nelson, 1987). Therefore, we investigate how tax preference can change the government’s choice of tax regimes between ad valorem and specific taxes when the public firm and the government have different objective functions in a model of mixed duopoly.The economic analyses of the government are divided into two broad aspects. One aspect emphasizes that the government operates in public interest. The other is that the government often sets targets for tax revenue collection and formulates tax policies accordingly. We therefore strive to understand a view of the government that lies between these two extremes. Our goal is to investigate whether the dominance of ad valorem taxes over specific taxes holds when the objective of the government is to maximize both social welfare and tax revenues. None of the previous studies have demonstrated the possible implications of the dominance of indirect tax schemes when the government has such an objective function1. This study attempts to fill this gap in the literature.In this study, the central assumption is that the government does not simply maximize social welfare. That is, we assume that the public firm maximizes social welfare, and that the government emphasizes both social welfare and its preference for tax revenues (i.e., a policy defined as the government’s “tax-inclusive social welfare,” hereinafter called the government’s payoff. See also Section 2.). While the criterion for relative tax efficiency in the literature is a higher tax revenue for a given total output under fairly general conditions, in this study, the government needs to indirectly control the level of industry output to balance social welfare and its tax revenue policy. It does so by choosing between the specific and ad valorem taxes as the optimal type of taxes2.In fact, the present study differs from the existing literature in at least two important ways. First, the existing studies on mixed oligopolies consider a monolithic entity that seeks to maximize social welfare at both the public firm and the government levels. Second, previous studies on unionized mixed oligopolies mainly focus on Cournot competition without tax effects, whereas our study investigates tax effects, and compares social welfare with the government’s payoff. Indeed, it also corresponds to the empirical results that in Europe, Japan, and the US, the government is strongly involved in the setting of public sector wages (Bordogna, 2003; Rose, 2004; Du Caju et al., 2008). From a recent empirical study, Bordogna (2003, pp. 62-63) pointed out that “even where bargaining has been decentralized, governments have often maintained strong, centralized, financial controls in order to contain public expenditures and avoid inflationary consequences of the decentralization process” (see also Brock and Lipsy (2003) and references therein). To investigate the optimal privatization policy, incorporating unions’ behavior into the different objectives of the government and the public firm can serve to explain the government’s use of taxes as a commitment device to control the unions’ wage demands. In general, a higher tax forces down both public and private firms’ wages since wages are strategic complements between the unions. As such, unions’ behavior is considered in this study.The present study shows several results: Given that one of the tax regimes is predetermined, privatization never improves welfare and is preferable for the government when it emphasizes tax revenue. However, when the tax regime is endogenously determined by the government, privatization is preferable from the viewpoint of social welfare if the government heavily emphasizes tax revenue from ad valorem taxes. Thus, there are conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government. That is, if the government heavily emphasizes tax revenue, then the government always has an incentive to levy a specific tax, while the public firm has an incentive to be levied an ad valorem tax. However, there are no conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government when the latter levies a specific tax if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small. Interestingly, the government never has an incentive for privatization when considering a choice of tax regimes between ad valorem and specific taxes.

2. Relationship with the Literature

- In this section, we discuss the relationship between our study and some other previous theoretical or empirical studies on government’s preference for tax revenues, and closely follow Choi (2011).We present some rationale for discussing objective functions from the perspective of government objectives. First, it has been argued in the literature that fiscal centralization increase the discretionary power of government when a Leviathan government exist. Therefore, the literature contains a number of puzzles for fiscal centralization and the size of the public sector (Oates, 1989). For example, Brennan and Buchanan (1980) formulated the hypothesis of a Leviathan government attempting to maximize revenue for its own private agenda3. A similar idea lies behind Niskanen’s (1971) model of a budget-maximizing bureau, although the bureau interacts with the government rather than with voters. This political power may fit with the analysis of the government4.Second, the objective of the public firm is not the same as that of the government because the government may find it hard to control some public firms. The advantage of the public firm is that it allows the government to distance itself from public sector activities that create discontent. This reduction of political interference is widely perceived as an improvement in social efficiency. According to Vickers and Yarrow (1988), in the postwar period in the UK, a principal objective of the legislation that established public corporations was to create an “arm’s length” relationship between the government and management. Unsurprisingly, managers (of the public firms) and politicians took full advantage of the discretion allowed them (Vickers and Yarrow (1988)). As argued above, we can justify the viewpoint that the objective of the public firm is to promote social welfare, while that of the government is to secure both social welfare and attainment of tax revenues.A recent study that comes closest to differentiating the government’s objective function is that by Kato (2008), who only focuses on the specific tax. Kato (2008) showed that the government’s choice of privatization of the public firm would depend on its preference for tax revenues if the following two assumptions hold true: First, the public firm fully emphasizes the social welfare net of tax revenues (which is defined as the sum of consumer and producer surpluses), and second, the government emphasizes both social welfare net of tax revenues and its preference for tax revenues. Rather than following Kato (2008) in ascribing the difference in objectives between the government and the public firm, Choi (2011) demonstrated that regardless of the government’s preference for tax revenues and the number of private firms, the government and the public firm do not always have an incentive for privatization without the choice of tax regimes. Considering that the specific tax involves a transfer within the economy, Choi’s (2011) assumption of the public firm differs from that of Kato (2008).

3. The Model

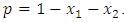

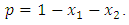

- Consider a mixed-duopoly situation for a homogeneous good that is supplied by a public firm and a private firm. Firm 1 is a profit-maximizing private firm and Firm 0 is a public firm that maximizes social welfare. Assume that the inverse demand is characterized by

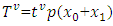

where

where  is the price of the good,

is the price of the good,  is the output level of the public firm, and

is the output level of the public firm, and  is the output level of the private firm. On the demand side of the market, the representative consumer’s utility is a quadratic function given by

is the output level of the private firm. On the demand side of the market, the representative consumer’s utility is a quadratic function given by We assume that the public and private firms are unionized and that the firms are homogeneous with respect to productivity. Given that

We assume that the public and private firms are unionized and that the firms are homogeneous with respect to productivity. Given that  is the number of workers employed in the ith firm, each firm adopts a constant returns-to-scale technology, where one unit of labor produces one unit of the final good. The price of labor (i.e., wage) that firm

is the number of workers employed in the ith firm, each firm adopts a constant returns-to-scale technology, where one unit of labor produces one unit of the final good. The price of labor (i.e., wage) that firm  has to pay is denoted by

has to pay is denoted by

Let

Let  denote the reservation wage. Taking

denote the reservation wage. Taking  as given, the union’s optimal wage-setting strategy,

as given, the union’s optimal wage-setting strategy,  regarding firm

regarding firm  is defined as follows:

is defined as follows: where

where  is the weight that the union attaches to the wage level. Following Ishida and Matsushima (2009) in the literature on unionized mixed duopoly, we assume that

is the weight that the union attaches to the wage level. Following Ishida and Matsushima (2009) in the literature on unionized mixed duopoly, we assume that  and

and  to demonstrate our results simply5. That is, the utility function of the union at the firm is its wage bill:

to demonstrate our results simply5. That is, the utility function of the union at the firm is its wage bill:  Thus, we consider the monopoly union model, which assumes that the unions set the wage, while the firms choose the employment level once the wage is set by the unions (see also Booth, 1995).In what follows, we assume that either an ad valorem tax or a specific tax rate is imposed on the public and private firms. To distinguish notations, the superscript “s” (respectively, “v”) is defined when the specific (respectively, ad valorem) tax is imposed on the public and private firms. In the case of an ad valorem tax,

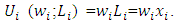

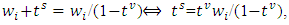

Thus, we consider the monopoly union model, which assumes that the unions set the wage, while the firms choose the employment level once the wage is set by the unions (see also Booth, 1995).In what follows, we assume that either an ad valorem tax or a specific tax rate is imposed on the public and private firms. To distinguish notations, the superscript “s” (respectively, “v”) is defined when the specific (respectively, ad valorem) tax is imposed on the public and private firms. In the case of an ad valorem tax,  the producer price,

the producer price,  for the good is obtained as

for the good is obtained as  where

where  denotes the consumer price for the good. If a specific tax is imposed, the producer price is defined by

denotes the consumer price for the good. If a specific tax is imposed, the producer price is defined by  Thus, introducing ad valorem taxation at the (tax inclusive) rate

Thus, introducing ad valorem taxation at the (tax inclusive) rate  and a specific tax of

and a specific tax of  each firm’s profit follows the function,

each firm’s profit follows the function,

respectively. The profit expression is the same when taxes are set such that

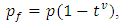

respectively. The profit expression is the same when taxes are set such that  if the total output is fixed to be the same under the two taxes. However, as stated in the introduction, we do not consider this case since the government has preference for tax revenues to balance social welfare and the government’s tax revenues by choosing between the specific and ad valorem taxes as the optimal type of tax.As usual, social welfare,

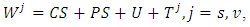

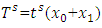

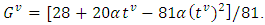

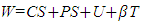

if the total output is fixed to be the same under the two taxes. However, as stated in the introduction, we do not consider this case since the government has preference for tax revenues to balance social welfare and the government’s tax revenues by choosing between the specific and ad valorem taxes as the optimal type of tax.As usual, social welfare,  can be defined as the sum of consumer surplus CS, producer surplus PS, the utilities of unions U, and total tax revenue

can be defined as the sum of consumer surplus CS, producer surplus PS, the utilities of unions U, and total tax revenue  collected by the government. Thus, the public firm aims to maximize social welfare, which is defined as

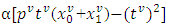

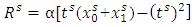

collected by the government. Thus, the public firm aims to maximize social welfare, which is defined as | (1) |

and

and  (respectively,

(respectively,  ) denotes the tax revenues when the specific (respectively, ad valorem) tax is imposed on both firms. As tax revenues collected under each type of tax,

) denotes the tax revenues when the specific (respectively, ad valorem) tax is imposed on both firms. As tax revenues collected under each type of tax,  is considered as a transfer within the economy. Furthermore, we also assume that the government’s payoff,

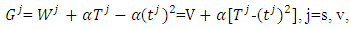

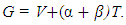

is considered as a transfer within the economy. Furthermore, we also assume that the government’s payoff,  is given by

is given by | (2) |

is the parameter that represents the weight of the government’s preference for tax revenues,

is the parameter that represents the weight of the government’s preference for tax revenues,  captures the cost of raising tax (i.e., the same weight is given to tax revenue and to the cost of raising tax)6 and

captures the cost of raising tax (i.e., the same weight is given to tax revenue and to the cost of raising tax)6 and  is defined as net tax revenues. Here, the government values the tax revenues,

is defined as net tax revenues. Here, the government values the tax revenues,  more than social welfare,

more than social welfare,  when

when  Otherwise, the government values the tax revenues less than social welfare when

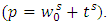

Otherwise, the government values the tax revenues less than social welfare when  . For the setup of different objectives, we introduce strict convexity of the cost function as an inefficiency of the government when it prefers tax revenues, in order to endogenize the inefficiency in collection and comparing ad valorem and specific taxes. This view of the government can be a focus for rent-seeking, in which the government is seen arguably as serving bureaucrats’ or politicians’ interests (e.g., Besley, 2006, chapter 1).Finally, the timing of the game is as follows. In the first stage, the government chooses whether or not to privatize the public firm, and simultaneously determines either the specific tax or ad valorem tax rate on the public and private firms. In the second stage, union i chooses its wage,

. For the setup of different objectives, we introduce strict convexity of the cost function as an inefficiency of the government when it prefers tax revenues, in order to endogenize the inefficiency in collection and comparing ad valorem and specific taxes. This view of the government can be a focus for rent-seeking, in which the government is seen arguably as serving bureaucrats’ or politicians’ interests (e.g., Besley, 2006, chapter 1).Finally, the timing of the game is as follows. In the first stage, the government chooses whether or not to privatize the public firm, and simultaneously determines either the specific tax or ad valorem tax rate on the public and private firms. In the second stage, union i chooses its wage,  after being made aware of each type of tax rate. In the third stage, firm i chooses its output

after being made aware of each type of tax rate. In the third stage, firm i chooses its output  simultaneously to maximize its respective objective, considering the type of tax imposed by the government and the wage levels.

simultaneously to maximize its respective objective, considering the type of tax imposed by the government and the wage levels.4. Results

- Before comparisons of indirect taxation and market type with the government’s payoff and social welfare, two cases are distinguished between the unionized mixed and privatized duopolies7: (i) a specific tax rate is imposed; and (ii) the tax is fixed by an ad valorem tax rate. Thus, the game is solved by backward induction, that is, the solution concept used is the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium.

4.1. Unionized Mixed Duopoly

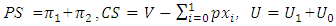

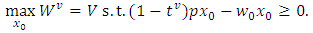

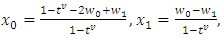

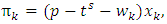

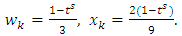

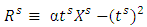

- First, we consider the case of specific tax under unionized mixed duopoly. In this case, the public firm’s objective is to maximize social welfare, which is defined as the sum of consumer surplus, individual firms’ profits, unions’ utilities, and specific tax revenues. Thus, given

and

and  for each firm

for each firm  , the public firm’s maximization problem is as follows:

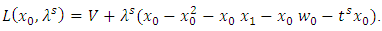

, the public firm’s maximization problem is as follows: As shown in Ishida and Matsushima (2009), the constraint implies there is some lower-bound restriction on the public firm’s profit, that is, the public firm faces a budget constraint8.If the multiplier of the budget constraint is denoted as

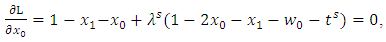

As shown in Ishida and Matsushima (2009), the constraint implies there is some lower-bound restriction on the public firm’s profit, that is, the public firm faces a budget constraint8.If the multiplier of the budget constraint is denoted as  the Lagrangian equation can be written as

the Lagrangian equation can be written as | (3) |

and the wage levels,

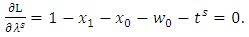

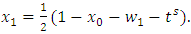

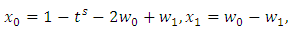

and the wage levels,  by solving the first-order conditions (3), we obtain

by solving the first-order conditions (3), we obtain | (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

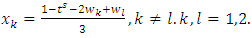

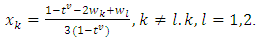

are obtained by maximizing

are obtained by maximizing  In addition, the substitution of each optimal wage into (7) yields the respective equilibrium outputs,

In addition, the substitution of each optimal wage into (7) yields the respective equilibrium outputs,  The equilibrium wages and outputs,

The equilibrium wages and outputs,  and

and  , respectively, can be obtained as follows:

, respectively, can be obtained as follows: | (9) |

in the mixed duopoly can be rewritten as

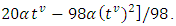

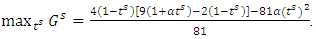

in the mixed duopoly can be rewritten as A straightforward computation yields the optimal tax rate as

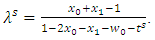

A straightforward computation yields the optimal tax rate as | (10) |

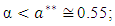

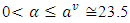

the optimal specific tax rate becomes positive. Conversely, when it is small, as in the case of

the optimal specific tax rate becomes positive. Conversely, when it is small, as in the case of  the optimal specific tax rate becomes negative10, and in the case of

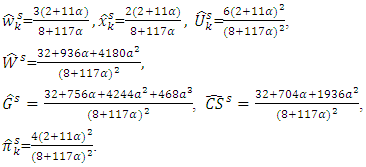

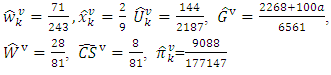

the optimal specific tax rate becomes negative10, and in the case of  the optimal specific tax rate is zero. We find that the greater the weight of the government’s preference for tax revenues, the higher will be the specific tax rate imposed by the government. Thus, by using (10), we obtain the following result. Lemma 1: Suppose that a specific tax rate is imposed on both public and private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, output, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit levels under a unionized mixed duopoly are given by

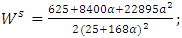

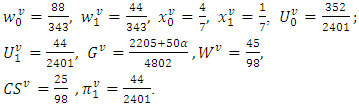

the optimal specific tax rate is zero. We find that the greater the weight of the government’s preference for tax revenues, the higher will be the specific tax rate imposed by the government. Thus, by using (10), we obtain the following result. Lemma 1: Suppose that a specific tax rate is imposed on both public and private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, output, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit levels under a unionized mixed duopoly are given by

From Lemma 1, it should be noted that the public firm would like to maximize

From Lemma 1, it should be noted that the public firm would like to maximize  by setting the output at the zero-profit level

by setting the output at the zero-profit level  Usually, in the absence of unions’ wage-bargaining power and when

Usually, in the absence of unions’ wage-bargaining power and when  the government would provide firms a subsidy to derive price down to the marginal cost. However, for

the government would provide firms a subsidy to derive price down to the marginal cost. However, for  the price would remain above the marginal cost, and a subsidy would encourage the unions to set higher wages. Therefore, a tax is required to be used to control the unions’ wage demands. By substituting Lemma 1 into (8), we obtain

the price would remain above the marginal cost, and a subsidy would encourage the unions to set higher wages. Therefore, a tax is required to be used to control the unions’ wage demands. By substituting Lemma 1 into (8), we obtain which shows that the budget constraint is binding.Second, we consider the case of ad valorem tax under unionized mixed duopoly. Given the ad valorem tax,

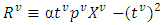

which shows that the budget constraint is binding.Second, we consider the case of ad valorem tax under unionized mixed duopoly. Given the ad valorem tax,  and

and  for each firm

for each firm  in the third stage, the public firm’s maximization problem is given as follows:

in the third stage, the public firm’s maximization problem is given as follows: Denoting the multiplier of the budget constraint

Denoting the multiplier of the budget constraint  and repeating the same process as in the previous case yields the first-order conditions of the Lagrangian equation with respect to

and repeating the same process as in the previous case yields the first-order conditions of the Lagrangian equation with respect to  and

and  with the optimal output for a private firm11.

with the optimal output for a private firm11. | (11) |

| (12) |

that maximizes union rent,

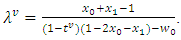

that maximizes union rent,  A straightforward computation yields the equilibrium wage and output. Repeating the same process as in previous cases yields the first-order conditions of the government’s payoff,

A straightforward computation yields the equilibrium wage and output. Repeating the same process as in previous cases yields the first-order conditions of the government’s payoff,

That is, the optimal tax rate is given by

That is, the optimal tax rate is given by  . Thus, by using

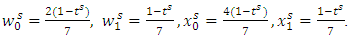

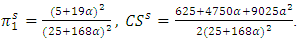

. Thus, by using  , we have the following result.Lemma 2: Suppose that an ad valorem tax rate is imposed on both public and private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit under a unionized mixed duopoly are given by

, we have the following result.Lemma 2: Suppose that an ad valorem tax rate is imposed on both public and private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit under a unionized mixed duopoly are given by Lemma 2 suggests that each firm's wage, output, and union's utility does not depend on

Lemma 2 suggests that each firm's wage, output, and union's utility does not depend on  since the ad valorem tax rate affects only the government's payoff. By substituting Lemma 2 into (12), we obtain

since the ad valorem tax rate affects only the government's payoff. By substituting Lemma 2 into (12), we obtain which shows that the budget constraint is binding.

which shows that the budget constraint is binding.4.2. Unionized Privatized Duopoly

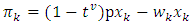

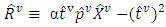

- This subsection investigates the equilibrium of a unionized privatized duopoly in the case of indirect taxes. As discussed in the basic model, consider the situation of a unionized privatized duopoly for a homogeneous good that is supplied by a profit-maximizing private firm

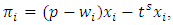

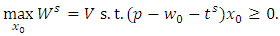

First, we consider the case of specific tax under unionized privatized duopoly. In the third stage, given

First, we consider the case of specific tax under unionized privatized duopoly. In the third stage, given  and

and  the firm

the firm  profit-maximization problem is to maximize

profit-maximization problem is to maximize  where

where  Hence, the symmetry across private firms implies that each firm’s output level is given by

Hence, the symmetry across private firms implies that each firm’s output level is given by | (13) |

Repeating the same process as in the previous subsection, straightforward computations and symmetry across private firms yield each firm’s wage and output:

Repeating the same process as in the previous subsection, straightforward computations and symmetry across private firms yield each firm’s wage and output: | (14) |

in a unionized privatized duopoly can be rewritten as

in a unionized privatized duopoly can be rewritten as A straightforward computation yields the following optimal tax rate in the unionized privatized duopoly:

A straightforward computation yields the following optimal tax rate in the unionized privatized duopoly: | (15) |

) the optimal tax rate becomes positive. Conversely, when it is small (as in the case when

) the optimal tax rate becomes positive. Conversely, when it is small (as in the case when  ), the optimal tax rate becomes negative. Further, in the case when

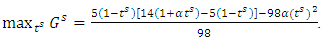

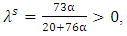

), the optimal tax rate becomes negative. Further, in the case when  the optimal tax rate is zero. Similar to the previous subsection, we have the following result.Lemma 3: Suppose that a specific tax rate is imposed on private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit levels under a unionized privatized duopoly are given by

the optimal tax rate is zero. Similar to the previous subsection, we have the following result.Lemma 3: Suppose that a specific tax rate is imposed on private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit levels under a unionized privatized duopoly are given by Similar to the previous case lemmas 3 and 4, we now analyze the case of the ad valorem tax in a unionized privatized duopoly. In the third stage, given

Similar to the previous case lemmas 3 and 4, we now analyze the case of the ad valorem tax in a unionized privatized duopoly. In the third stage, given  and

and  , the firm

, the firm  profit-maximization problem is to maximize

profit-maximization problem is to maximize  where

where  Hence, the symmetry across private firms implies that each output level is given by

Hence, the symmetry across private firms implies that each output level is given by | (16) |

that maximizes union rent,

that maximizes union rent,  A straightforward computation yields the equilibrium wage and output. Repeating the same process as in the previous cases yields the first-order conditions of the government’s payoff,

A straightforward computation yields the equilibrium wage and output. Repeating the same process as in the previous cases yields the first-order conditions of the government’s payoff,  That is, the optimal tax rate is given by

That is, the optimal tax rate is given by  Thus, by using

Thus, by using  we can compute each equilibrium value as follows:Lemma 4: Suppose that an ad valorem tax rate is imposed on private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit under a unionized privatized duopoly are given by

we can compute each equilibrium value as follows:Lemma 4: Suppose that an ad valorem tax rate is imposed on private firms. Then, the equilibrium wages, outputs, union’s utilities, government’s payoff, social welfare, consumer surplus, and private firm’s profit under a unionized privatized duopoly are given by

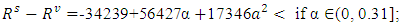

5. Comparisons of Indirect Taxation and Market Type

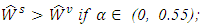

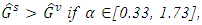

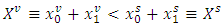

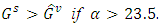

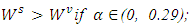

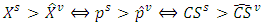

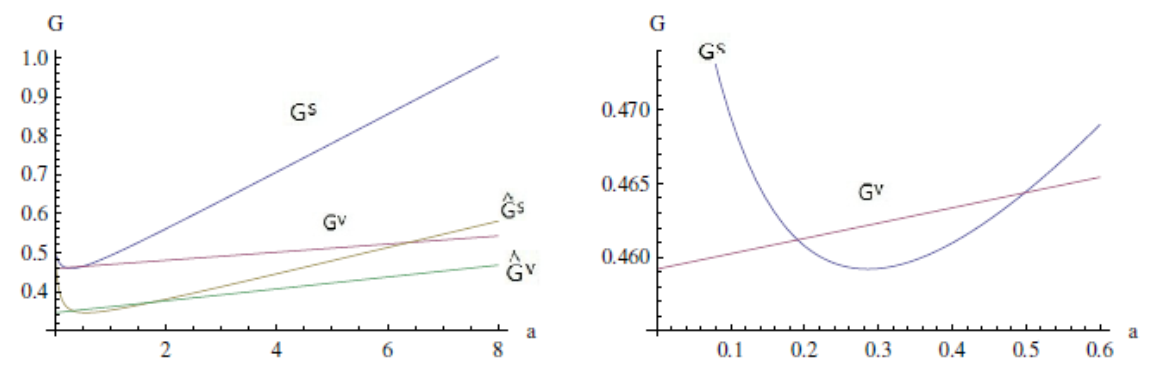

- Having derived the equilibrium for the two types of tax regimes in the previous section, we will determine either exogenously or endogenously the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium in the first stage. If the type of taxes is fixed, we can state the following results from easy comparisons of calculations that we can omit12:Proposition 1: Suppose that the type of taxes is fixed under either mixed or privatized duopoly. Then, in the first stage,(i)

Moreover,

Moreover,  (ii)

(ii)  if

if  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  if

if  The intuition for Proposition 1(i) is as follows. When imposing specific tax, the price under a unionized mixed duopoly is always smaller than under a unionized privatized duopoly

The intuition for Proposition 1(i) is as follows. When imposing specific tax, the price under a unionized mixed duopoly is always smaller than under a unionized privatized duopoly  For this reason, the government uses tax as a commitment device to control the union’s wage demands to maintain lower wage levels under unionized mixed duopoly

For this reason, the government uses tax as a commitment device to control the union’s wage demands to maintain lower wage levels under unionized mixed duopoly  Thus, lower wages under the unionized mixed duopoly work to improve welfare by increasing the total output, thus raising the tax revenues. This leads to more output under a unionized mixed duopoly than under a unionized privatized duopoly. On the other hand, privatization under specific taxes leads to a reduction in total output and an increase in market price (i.e.,

Thus, lower wages under the unionized mixed duopoly work to improve welfare by increasing the total output, thus raising the tax revenues. This leads to more output under a unionized mixed duopoly than under a unionized privatized duopoly. On the other hand, privatization under specific taxes leads to a reduction in total output and an increase in market price (i.e.,  and

and  ). This implies that the private firm under the privatization obtains a higher profit and produces less total output since regardless of condition

). This implies that the private firm under the privatization obtains a higher profit and produces less total output since regardless of condition  while

while  However, when imposing ad valorem tax with

However, when imposing ad valorem tax with  and

and  , a higher ad valorem tax forces down both public and private firms’ wages since wages are strategic complements between the unions, while reducing the firms’ revenue. The latter effect dominates the former effect, which leads to greater reduction in total output and an increase in market price under a unionized privatized duopoly than those under a unionized mixed duopoly when imposing ad valorem tax. Hence, imposing ad valorem tax also works to decrease firms’ revenue, even though the government uses tax as a commitment device to control the union’s wage demands to maintain lower wage levels. On the other hand, Proposition 1(ii) states that if the government levies ad valorem tax at the first stage, comparisons of the government’s payoff in the first stage can vary with

, a higher ad valorem tax forces down both public and private firms’ wages since wages are strategic complements between the unions, while reducing the firms’ revenue. The latter effect dominates the former effect, which leads to greater reduction in total output and an increase in market price under a unionized privatized duopoly than those under a unionized mixed duopoly when imposing ad valorem tax. Hence, imposing ad valorem tax also works to decrease firms’ revenue, even though the government uses tax as a commitment device to control the union’s wage demands to maintain lower wage levels. On the other hand, Proposition 1(ii) states that if the government levies ad valorem tax at the first stage, comparisons of the government’s payoff in the first stage can vary with  Because

Because  and

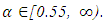

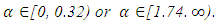

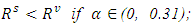

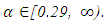

and  , an increase in the producer’s price requires a greater increase in the consumer price under privatized duopoly than under unionized mixed duopoly. This leads to increased ad valorem tax revenue if the government’s preference for tax revenue is sufficiently large. On the other hand, a decrease in consumer price reduces the net price received by each firm by less than the decrease in consumer price. This part of the cost is borne by the government, and will be smaller under a mixed duopoly. As a result, when the government levies an ad valorem tax, conflicts of interest with respect to privatization will always arise between the public firm and the government if its preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large. Proposition 1 differs from the results of Mujumdar and Pal (1998), which demonstrated that privatization can increase both social welfare and tax revenues. In contrast, our study shows that when the government and the public firm do not have the same objectives, privatization is not always desirable in terms of social welfare from the viewpoint of the public firm.Moreover, we can state the following results when the type of markets is fixed.Proposition 2: Suppose that the type of markets is fixed under either ad valorem or specific tax. Then, in the first stage,(i)

, an increase in the producer’s price requires a greater increase in the consumer price under privatized duopoly than under unionized mixed duopoly. This leads to increased ad valorem tax revenue if the government’s preference for tax revenue is sufficiently large. On the other hand, a decrease in consumer price reduces the net price received by each firm by less than the decrease in consumer price. This part of the cost is borne by the government, and will be smaller under a mixed duopoly. As a result, when the government levies an ad valorem tax, conflicts of interest with respect to privatization will always arise between the public firm and the government if its preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large. Proposition 1 differs from the results of Mujumdar and Pal (1998), which demonstrated that privatization can increase both social welfare and tax revenues. In contrast, our study shows that when the government and the public firm do not have the same objectives, privatization is not always desirable in terms of social welfare from the viewpoint of the public firm.Moreover, we can state the following results when the type of markets is fixed.Proposition 2: Suppose that the type of markets is fixed under either ad valorem or specific tax. Then, in the first stage,(i)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  (ii)

(ii)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  (iii)

(iii)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  (iv)

(iv)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  Proof: See the appendix for parts (i) and (ii). When comparing the government’s payoff, it can calculate simply. Q.E.D.The intuition for Proposition 2 (i) is as follows. Consider the condition that

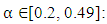

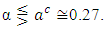

Proof: See the appendix for parts (i) and (ii). When comparing the government’s payoff, it can calculate simply. Q.E.D.The intuition for Proposition 2 (i) is as follows. Consider the condition that  In this case, the price under the imposition of the specific tax rate is smaller than that under that of the ad valorem tax rate13. However, because

In this case, the price under the imposition of the specific tax rate is smaller than that under that of the ad valorem tax rate13. However, because  and

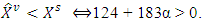

and  , a higher ad valorem tax forces down both public and private firms’ wages, while reducing the firms’ revenue. The latter effect dominates the former effect, which leads to a greater reduction in total output (i.e., higher market price) when imposing ad valorem tax than that when imposing specific tax if

, a higher ad valorem tax forces down both public and private firms’ wages, while reducing the firms’ revenue. The latter effect dominates the former effect, which leads to a greater reduction in total output (i.e., higher market price) when imposing ad valorem tax than that when imposing specific tax if  and vice versa. This condition implies that the total output level under ad valorem tax is smaller than that under specific tax (i.e.,

and vice versa. This condition implies that the total output level under ad valorem tax is smaller than that under specific tax (i.e.,  if

if  ). As a result, it turns out that social welfare under ad valorem tax is smaller than that under specific tax if

). As a result, it turns out that social welfare under ad valorem tax is smaller than that under specific tax if  However, if

However, if  these effects are reversed. When comparing

these effects are reversed. When comparing  with

with  , similar explanations are adopted by using the critical value of

, similar explanations are adopted by using the critical value of  Note that we will mention the intuitions of Proposition 2 (iii) and (iv) later, because endogenous comparisons can exclude off the equilibrium paths.Finally, we need to investigate endogenously the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium in the first stage. Since the government determines the choice variables (the type of taxes and markets) in the first stage, the government chooses the best choice from the four options of Section 4. However, we do not need to compare

Note that we will mention the intuitions of Proposition 2 (iii) and (iv) later, because endogenous comparisons can exclude off the equilibrium paths.Finally, we need to investigate endogenously the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium in the first stage. Since the government determines the choice variables (the type of taxes and markets) in the first stage, the government chooses the best choice from the four options of Section 4. However, we do not need to compare  with

with  and

and  with

with  since

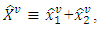

since  in Proposition 1 (i). This implies that at the stage of choosing the type of markets and taxes, we can exclude the case of the unionized privatized duopoly under specific tax. Moreover, considering the social welfare of the results of Propositions 1 and 2, we see the impact of the government's payoff at the stage of choosing the type of taxes when we recall that the “net” tax revenue under ad valorem tax is

in Proposition 1 (i). This implies that at the stage of choosing the type of markets and taxes, we can exclude the case of the unionized privatized duopoly under specific tax. Moreover, considering the social welfare of the results of Propositions 1 and 2, we see the impact of the government's payoff at the stage of choosing the type of taxes when we recall that the “net” tax revenue under ad valorem tax is

and that collected under specific tax is

and that collected under specific tax is  (let

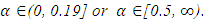

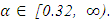

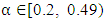

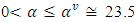

(let  denote net tax revenue under privatization with each tax regime). Therefore, we can state the following results15.Proposition 3: Suppose that the government prefers either specific or ad valorem tax revenue when it considers such type of markets as an option, and the assumption holds. Then, in the first stage,(i)

denote net tax revenue under privatization with each tax regime). Therefore, we can state the following results15.Proposition 3: Suppose that the government prefers either specific or ad valorem tax revenue when it considers such type of markets as an option, and the assumption holds. Then, in the first stage,(i)  otherwise,

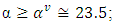

otherwise,  if

if  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  (iv)

(iv)  (v)

(v)  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  (vi)

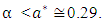

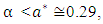

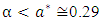

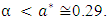

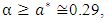

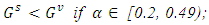

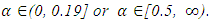

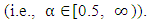

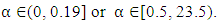

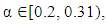

(vi)  The intuition for Proposition 3 (i) is as follows16. Consider the first case where the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small (i.e.,

The intuition for Proposition 3 (i) is as follows16. Consider the first case where the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small (i.e.,  in Proposition 3 (i)) under a mixed duopoly. In this case, due to the fact that

in Proposition 3 (i)) under a mixed duopoly. In this case, due to the fact that  and

and  there is higher net tax revenue under ad valorem tax. Besides this direct effect, social welfare under specific tax is higher than that under ad valorem tax. We call the former the “net tax effect” and the latter the “welfare effect.” With Propositions 3 (i) and (iii), the government’s payoff improvement is possible when the welfare effect under specific tax dominates the net tax effect under ad valorem tax, once its preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small17. On the other hand, it is important to notice that in a mixed duopoly, the ad valorem tax rate is higher than the specific tax rate if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large

there is higher net tax revenue under ad valorem tax. Besides this direct effect, social welfare under specific tax is higher than that under ad valorem tax. We call the former the “net tax effect” and the latter the “welfare effect.” With Propositions 3 (i) and (iii), the government’s payoff improvement is possible when the welfare effect under specific tax dominates the net tax effect under ad valorem tax, once its preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small17. On the other hand, it is important to notice that in a mixed duopoly, the ad valorem tax rate is higher than the specific tax rate if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large  Due to the fact that

Due to the fact that  owing to lower equilibrium output under specific tax, the implication is that

owing to lower equilibrium output under specific tax, the implication is that  as in Proposition 3 (i). However, the welfare effect under ad valorem tax is dominated by the net tax effect under specific tax as Proposition 3 (iii) states. In addition, if the government’s preference for tax revenues falls in the middle range,

as in Proposition 3 (i). However, the welfare effect under ad valorem tax is dominated by the net tax effect under specific tax as Proposition 3 (iii) states. In addition, if the government’s preference for tax revenues falls in the middle range,  under a mixed duopoly, the government’s payoff under ad valorem tax is larger than that under specific tax since both welfare and net tax effects under ad valorem tax are always greater than under specific tax.Finally, the intuition for Proposition 3 (ii) is as follows. The price under specific tax is higher than that under ad valorem tax since total output under specific tax is larger if

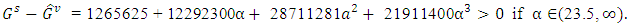

under a mixed duopoly, the government’s payoff under ad valorem tax is larger than that under specific tax since both welfare and net tax effects under ad valorem tax are always greater than under specific tax.Finally, the intuition for Proposition 3 (ii) is as follows. The price under specific tax is higher than that under ad valorem tax since total output under specific tax is larger if  In this case, due to the fact that

In this case, due to the fact that  , lowering output under specific tax in mixed duopoly, it turns out that

, lowering output under specific tax in mixed duopoly, it turns out that  as in Proposition 3 (vi). However, the welfare effect under ad valorem tax is dominated by the net tax effect under specific tax, as stated in Proposition 3 (iv). Therefore, we obtain Proposition 3 (ii). Hence, noting either critical value,

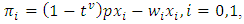

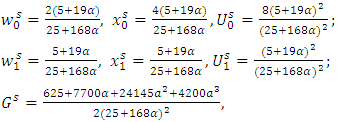

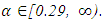

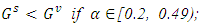

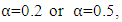

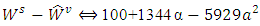

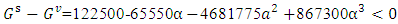

as in Proposition 3 (vi). However, the welfare effect under ad valorem tax is dominated by the net tax effect under specific tax, as stated in Proposition 3 (iv). Therefore, we obtain Proposition 3 (ii). Hence, noting either critical value,  we compare the government’s payoff under both market competitions with both tax regimes. The graphs of comparisons of G are shown in Figure 1.

we compare the government’s payoff under both market competitions with both tax regimes. The graphs of comparisons of G are shown in Figure 1. | Figure 1. Comparisons of government payoff |

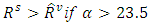

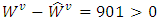

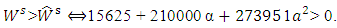

However, if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large, while the public firm has the incentive to be levied an ad valorem tax, the government always has an incentive to levy specific tax:

However, if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large, while the public firm has the incentive to be levied an ad valorem tax, the government always has an incentive to levy specific tax:  and

and  Interestingly, in line with Proposition 3, the government never has an incentive for privatization. Hence, Propositions 3 shows that depending on the government’s preference for tax revenues, the conflict between these two views of objective functions typically induces a conflict with regard to imposing either tax.

Interestingly, in line with Proposition 3, the government never has an incentive for privatization. Hence, Propositions 3 shows that depending on the government’s preference for tax revenues, the conflict between these two views of objective functions typically induces a conflict with regard to imposing either tax.6. Concluding Remarks

- This study investigated changes in social welfare and the government’s payoff on the basis of different objective functions of the government and the public firm. Specifically it compared the efficiency of ad valorem taxes with that of specific taxes in both a unionized mixed duopoly and privatization. We found that the comparative effect on social welfare and government’s payoff is endogenously determined by welfare and net tax effects as follows: There are no conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government when the government levies a specific tax under unionized mixed duopoly if its preference for tax revenues is sufficiently small. However, if the government’s preference for tax revenues is sufficiently large, while the public firm has the incentive to be levied an ad valorem tax, the government always has an incentive to levy specific tax. Interestingly, the government never has an incentive for privatization. This means that the government doesn’t want to privatization compared to levy tex.However, there remains much to be explored regarding the empirical impact of tax structure and asymmetric Bertrand competition with unionized mixed oligopoly. Moreover, there could be important economic implications if the analysis is expanded to include the entry of private firms and varying motives for bargaining among firms in the existing framework of mixed oligopolistic markets. The extension of our model in these directions remains an agendum for future research.

Appendix: Proofs

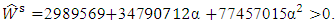

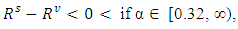

- Proof of Proposition 1(i): Comparing

with

with  yields

yields  , and comparing

, and comparing  with

with  yields

yields

Moreover, comparing

Moreover, comparing  with

with  yields

yields  (ii): Comparing

(ii): Comparing  with

with  yields

yields if

if  otherwise

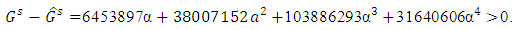

otherwise  Proof of Proposition 2Since

Proof of Proposition 2Since  in Proposition 1,

in Proposition 1,  is excluded by choosing

is excluded by choosing  when comparing social welfare.(i): Comparing

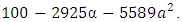

when comparing social welfare.(i): Comparing  with

with  , and

, and  with

with  yields

yields  and

and  and

and  By applying to a discriminant and ignoring the nonpositive roots for

By applying to a discriminant and ignoring the nonpositive roots for  through the assumption, we have the root

through the assumption, we have the root  and

and  Since the maximum value is attained from

Since the maximum value is attained from  (respectively,

(respectively,  ),

),  (respectively,

(respectively,  if

if  (respectively,

(respectively,  ); otherwise,

); otherwise,

(respectively,

(respectively,  ) if

) if  (respectively,

(respectively,  ).Proof of Proposition 3Since

).Proof of Proposition 3Since  in Proposition 1,

in Proposition 1,  is excluded by choosing

is excluded by choosing  when comparing government’s payoff. Moreover, when comparing

when comparing government’s payoff. Moreover, when comparing  with

with  the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to start from

the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to start from  because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose

because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose  rather than

rather than  Also, if

Also, if  in the range of

in the range of  from Proposition 1(ii), it should compare

from Proposition 1(ii), it should compare  with

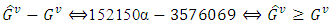

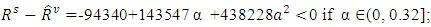

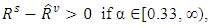

with  (i) and (ii): Comparing

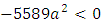

(i) and (ii): Comparing  with

with  and

and  with

with  yield

yield if

if  Otherwise,

Otherwise,  if

if

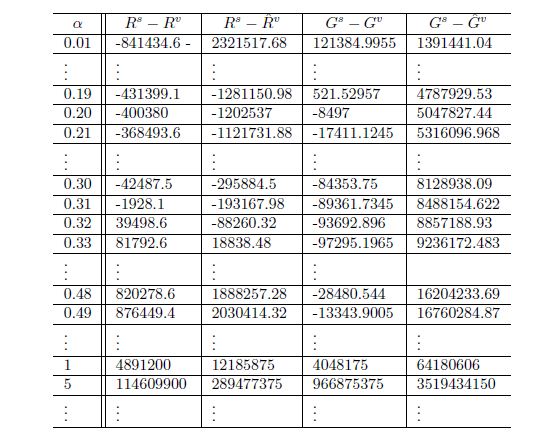

Other ways of straightforward calculations of Proposition 3 are shown in Table A-1. Using numerical examples to illustrate the impact of

Other ways of straightforward calculations of Proposition 3 are shown in Table A-1. Using numerical examples to illustrate the impact of  straightforward computations yield as follows.

straightforward computations yield as follows.

|

with

with  and

and  with

with  yield

yield otherwise

otherwise

otherwise

otherwise  respectively. However, when comparing the government’s payoff in the case of mixed duopoly and specific tax and that under the case of privatization and ad valorem tax, the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to begin from

respectively. However, when comparing the government’s payoff in the case of mixed duopoly and specific tax and that under the case of privatization and ad valorem tax, the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to begin from  because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose

because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose  Thus, when

Thus, when  the net tax revenue under the case of privatization and ad valorem tax is always smaller than that under the case of a mixed duopoly and specific tax.(iv): Comparing

the net tax revenue under the case of privatization and ad valorem tax is always smaller than that under the case of a mixed duopoly and specific tax.(iv): Comparing  with

with  yields

yields

Notes

- 1. Two exceptions are Anant et al. (1995) and Pal and Sharma (2013). The former study showed how to model government-firm interactions and serves as a guide for other models, by adopting the revenue-maximization assumption of the government with a monopoly firm and relaxing key assumptions of the models. The latter study considered a linear combination of net tax revenue and social welfare to endogenize the objective function of governments in a model of tax competition. In this study, we use the non-linear, rather than the linear, combination for the analysis. To the best of our knowledge, such an attempt has not been made in the relevant literature.2. In a setting, where the specific tax is adjusted to ensure that both specific and ad valorem taxes lead to the same level of industry output, there exists an ad valorem tax that yields the same social welfare with higher tax revenue for the government as any given specific tax. Under this setting, as in the literature, even if the government emphasizes both social welfare and its preference for tax revenues, there are no conflicts of interest between the public firm and the government. This irrelevant case is excluded in the present study.3. In theoretical studies of the Leviathan government, Edwards and Keen (1996) and Rauscher (2000) used formalized tax-competition models to address the issue and showed that the results of tax competition are ambiguous. For more detailed treatment of the Leviathan government, recent theoretical and empirical studies include Oates (1989), Keen and Kotsogiannis (2002), and Brulhart and Jametti (2006).4. According to Persson and Tabellini (2002, p. 7), the government raises taxes and spends the resulting revenue on three items: (1) general public goods; (2) narrowly targeted redistribution to well-defined groups; and (3) rents for politicians.5. As Ishida and Matsushima (2009), Barcena-Ruiz and Garzon (2009), Horrn and Wolinsky (1988), and Haucap and Wey (2004) have suggested, this is because wage claims are decided by the elasticity of labor demand rather than the firm’s profit, as a special case of Nash bargaining solution, the monopoly union model (Oswald, 1982) is frequently adopted. Even if the present model of union's utility loses generality, the wage bill maximization enables us to gain insights; otherwise, it complicates the comparison between a specific tax with an ad valorem tax under either privatization or mixed duopoly.6. If this cost is not allowed, the government’s payoff can indefinitely raise its ad valorem tax rate because the optimal ad valorem tax level of the government is independent of the government’s preference for tax revenues. Moreover, the cost-raising feature can be interpreted as the political cost of raising tax (e.g., perks or lobby cost) or X-inefficiency within the government (see, for example, Leibenstein, 1987). More clear extensions and government’s cost analysis of depending on total output are left to future research to develop the analysis more generally. Another possible way to solve this problem is to interpret the taxes collected by the government as

Parameter

Parameter  represents the percentage of taxes paid by firms that goes to the government; the remaining

represents the percentage of taxes paid by firms that goes to the government; the remaining  percent represents the social cost of collecting the taxes (e.g., bureaucracy). Taking into account this assumption, social welfare is defined as

percent represents the social cost of collecting the taxes (e.g., bureaucracy). Taking into account this assumption, social welfare is defined as  and the government’s payoff can be defined as

and the government’s payoff can be defined as  In general, incorporating

In general, incorporating  into a transfer within the economy makes the effect on social welfare and government’s payoff complicated.7. We will discuss indirect taxation models assuming that the government chooses either mixed duopoly or privatization. Later, we will mention this why we use the fixed decision.8. In this model, if the public firm does not face the budget constraint, the public firm’s union can indefinitely raise its wage level because the optimal output level of the public firm is independent of the wage level.9. Some readers may argue that the budget constraint may be non-binding on off-equilibrium paths. Kuhn-Tucker conditions regarding off-equilibrium paths for any values of

into a transfer within the economy makes the effect on social welfare and government’s payoff complicated.7. We will discuss indirect taxation models assuming that the government chooses either mixed duopoly or privatization. Later, we will mention this why we use the fixed decision.8. In this model, if the public firm does not face the budget constraint, the public firm’s union can indefinitely raise its wage level because the optimal output level of the public firm is independent of the wage level.9. Some readers may argue that the budget constraint may be non-binding on off-equilibrium paths. Kuhn-Tucker conditions regarding off-equilibrium paths for any values of  are available from the author upon request. To provide correct calculations, we present Supplementary Material, which is only available for the reviewers and editor.10. This implies that the government needs to intervene by considering a subsidy, such as a production subsidy. In reality, governments often directly provide subsidies to many sectors, including medical care, energy, finance, and international trade. According to Tomaru and Saito (2010, p. 42), “in Japan, the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency provides private firms with subsidies in order to encourage distribution services and enhance their efficiency. Yamato Transport, which is one of the major delivery enterprisers and competes against Japan Post which is a semi-public firm, is subsidized.” Thus, studies on optimal subsidy in mixed oligopolies have gained prominence in recent years (e.g., White, 1996; Tomaru and Saito, 2010; Tomaru and Kiyono, 2010).11. To solve the Lagrangian equation, suppose that the budget constraint is momentarily binding. We check ex-post that this constraint is binding.12. To provide correct calculations, we present Supplementary Material, which is only available for the reviewers and editor.13. Thus, comparing each consumer surplus depends on

are available from the author upon request. To provide correct calculations, we present Supplementary Material, which is only available for the reviewers and editor.10. This implies that the government needs to intervene by considering a subsidy, such as a production subsidy. In reality, governments often directly provide subsidies to many sectors, including medical care, energy, finance, and international trade. According to Tomaru and Saito (2010, p. 42), “in Japan, the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency provides private firms with subsidies in order to encourage distribution services and enhance their efficiency. Yamato Transport, which is one of the major delivery enterprisers and competes against Japan Post which is a semi-public firm, is subsidized.” Thus, studies on optimal subsidy in mixed oligopolies have gained prominence in recent years (e.g., White, 1996; Tomaru and Saito, 2010; Tomaru and Kiyono, 2010).11. To solve the Lagrangian equation, suppose that the budget constraint is momentarily binding. We check ex-post that this constraint is binding.12. To provide correct calculations, we present Supplementary Material, which is only available for the reviewers and editor.13. Thus, comparing each consumer surplus depends on

if

if  14. By comparing

14. By comparing  with

with  we get

we get  if

if  otherwise,

otherwise,  if

if  15. Since a comparison of the government’s payoff and net tax revenue is easily possible from direct calculations (i.e., Proposition 3 (i)-(vi)), which are available from the author upon request. Moreover, when comparing

15. Since a comparison of the government’s payoff and net tax revenue is easily possible from direct calculations (i.e., Proposition 3 (i)-(vi)), which are available from the author upon request. Moreover, when comparing  with

with  the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to begin from

the parameter of the government’s preference for tax revenues needs to begin from  because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose

because of Proposition 1(ii). Otherwise, the government will choose  rather than

rather than  Also, if

Also, if  in the range of

in the range of  from Proposition 1(ii), it should compare

from Proposition 1(ii), it should compare  with

with  16. The intuition for Proposition 3 (v) and (vi) is already explained in Proposition 2. Hence, as stated in the intuition for Proposition 2 (i), when comparing

16. The intuition for Proposition 3 (v) and (vi) is already explained in Proposition 2. Hence, as stated in the intuition for Proposition 2 (i), when comparing  with

with  we get

we get  17. Strictly speaking, in the case of

17. Strictly speaking, in the case of  where

where  the government’s payoff under ad valorem tax is larger than that under specific tax, since both welfare and net tax effects under ad valorem taxes are always greater than those under specific taxes.

the government’s payoff under ad valorem tax is larger than that under specific tax, since both welfare and net tax effects under ad valorem taxes are always greater than those under specific taxes. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML