-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Game Theory

p-ISSN: 2325-0046 e-ISSN: 2325-0054

2016; 5(1): 9-15

doi:10.5923/j.jgt.20160501.02

On the Behavior of Strategies in Hawk-Dove Game

Essam EL-Seidy

Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Essam EL-Seidy, Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The emergence of cooperative behavior in human and animal societies is one of the fundamental problems in biology and social sciences. In this article, we study the evolution of cooperative behavior in the hawk dove game. There are some mechanisms like kin selection, group selection, direct and indirect reciprocity can evolve the cooperation when it works alone. Here we combine two mechanisms together in one population. The transformed matrices for each combination are determined. Some properties of cooperation like risk-dominant (RD) and advantageous (AD) are studied. The property of evolutionary stable (ESS) for strategies used in this article is discussed.

Keywords: Hawk-dove game, Evolutionary game dynamics, of evolutionary stable strategies (ESS), Kin selection, Direct and Indirect reciprocity, Group selection

Cite this paper: Essam EL-Seidy, On the Behavior of Strategies in Hawk-Dove Game, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 9-15. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20160501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

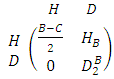

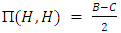

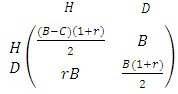

- Game theory provides a quantitative framework for analyzing the behavior of rational players. The theory of iterated games in particular provides a systematic framework to explore the players' relationship in a long-term. It has been an important tool in the behavioral and biological sciences and it has been often invoked by economists, political scientists, anthropologists and other scientists who were interested in human cooperation ([1], [2], [11], [12]).The evolutionary game theory has proven to be excellent for studying the evolution and success of different behavioral patterns in human as well as animal societies ([18]). The two games receiving the most attention are the hawk–dove and the Prisoner’s Dilemma game ([3]). In both games, the cooperative strategy, i.e. dove strategy in the hawk– dove game, warrants the highest collective payoff that is equally shared among the players. Mutual cooperation is, however, challenged by the defecting strategy, i.e. hawk strategy in the Hawk–Dove game, that promises the defector a higher income at the expense of the neighboring cooperator. The crucial difference that distinguishes both games is the way defectors are punished when facing each other. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma game, a defector encountering another defector still earns more than a cooperator facing a defector, whilst in the hawk–dove game the ranking of these two payoffs is switched. Thus, in the hawk–dove game a cooperator facing a defector earns more than a defector playing with another defector. This seemingly minute difference between both games has a rather profound effect on the success of both strategies. In particular, whilst by the Prisoner’s Dilemma spatial structure often facilitates cooperation this is often not the case in the hawk–dove game ([14]).The Hawk-Dove game ([18]), also known as the snowdrift game or the chicken game, is used to study a variety of topics, from the evolution of cooperation to nuclear brinkmanship ([8], [22]). The basic idea of the Hawk-Dove (or chicken) game is that two opponents compete for a resource. The resource brings a benefit B to the one who wins it. In this game, opponents have the opportunity to play Hawk and fight (i.e., defect), or play Dove and give way (i.e., cooperate). The payoffs are maximized when both players give way and play Dove (cooperate). Unfortunately, in a world of doves, it pays to defect and play Hawk (defect). This game’s payoffs can be couched in terms of costs and benefits and modified to consider the joint consequences of kin selection and reciprocal altruism. Fighting is, however, dangerous and the looser of a fight has to bear a cost C. If a Hawk meets a Hawk, they will fight and one of them will win the resource. Thus, the average payoff of a Hawk meeting a Hawk is

. If a Hawk meets a Dove the Dove immediately withdraws, so its payoff is zero, while the payoff of the Hawk is B. If two Doves meet, the one who first gets hold of the resource keeps it while the other does not fight for it. Thus, the average payoff for a Dove meeting a Dove is

. If a Hawk meets a Dove the Dove immediately withdraws, so its payoff is zero, while the payoff of the Hawk is B. If two Doves meet, the one who first gets hold of the resource keeps it while the other does not fight for it. Thus, the average payoff for a Dove meeting a Dove is  . The strategic form of the game is given by the payoff matrix:

. The strategic form of the game is given by the payoff matrix: | (1) |

2. Evolutionary Game Theory

- The first ideas of evolutionary game theory showed up in the papers by Hamilton [13], Trivers [25], and Maynard Smith and Price [18]. Evolutionary game theory studies the behavior of large populations of agents who repeatedly engage in strategic interactions. Evolutionary game theory varies from classical game theory by concentrating more on the dynamics of strategy change as impacted not singularly by the nature of the various competing strategies, but by the impact of the frequency with which those various competing strategies are found in the population. Evolutionary game theory has turned out to be precious in clarifying numerous mind boggling and testing parts of science. It has been especially useful in building up the premise of altruistic behaviors inside of the connection of Darwinian procedure. In spite of its cause and unique reason, evolutionary game theory has become of increasing interest to economists, sociologists, anthropologists, and philosophers ([1], [7], [17]).

2.1. Evolutionarily Stable Strategies (ESS)

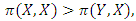

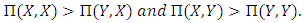

- The idea of evolutionary stable strategies was defined and introduced by the British biologist John Maynard Smith and George R. Price in a 1973 ([20]). The idea is that one strategy in a given contest, on average, will win over any other strategy. The strategy ought to additionally have the advantage of doing great when set against adversaries utilizing the same strategy. This is important, because a successful strategy is likely to be common and the player will probably have to compete with others who are employing it. It does not have to be a single evolutionary strategy. It can be a combination of strategies, or a combination of players where every utilize only one strategy. Maynard Smith and Price specify two conditions for a strategy

to be an

to be an  . EitherI.

. EitherI.  that is, the payoff for playing

that is, the payoff for playing  against (another playing)

against (another playing)  is greater than that for playing any other strategy

is greater than that for playing any other strategy  against

against  for all

for all  OrII.

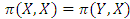

OrII.  and

and  , that is, the payoff of playing

, that is, the payoff of playing  against itself is equal to that of playing

against itself is equal to that of playing  against

against  but the payoff of playing

but the payoff of playing  against

against  is less than that of playing

is less than that of playing  against

against  for all

for all  Note that either (I) or (II) will do and that the previous is a more grounded condition than the recent. Clearly, if (I) gets, the Y invader commonly loses against X, and along these lines it can't even start to increase with any achievement. If (II) gets, the Y invader does as well against X as X itself, but it loses to X against other Y invaders, and therefore it cannot multiply. In short,

Note that either (I) or (II) will do and that the previous is a more grounded condition than the recent. Clearly, if (I) gets, the Y invader commonly loses against X, and along these lines it can't even start to increase with any achievement. If (II) gets, the Y invader does as well against X as X itself, but it loses to X against other Y invaders, and therefore it cannot multiply. In short,  players cannot successfully invade a population of X players. It is conceivable to present a strategy that is stronger than an

players cannot successfully invade a population of X players. It is conceivable to present a strategy that is stronger than an  , namely, an unbeatable strategy. Strategy

, namely, an unbeatable strategy. Strategy  is unbeatable if, given whatever other strategy

is unbeatable if, given whatever other strategy  :

: An unbeatable strategy is the most powerful strategy, because it strictly dominates any other strategy; however it is additionally uncommon, and subsequently in exceptionally constrained use.

An unbeatable strategy is the most powerful strategy, because it strictly dominates any other strategy; however it is additionally uncommon, and subsequently in exceptionally constrained use.2.2. Evolutionary Game Dynamics

- Evolutionary game dynamics is the application of population dynamical methods to game theory. It has been introduced by evolutionary biologists (such as William D. Hamilton and John Maynard Smith), anticipated in part by classical game theorists. Consider a game between two strategies,

and

and  , given by the payoff matrix:

, given by the payoff matrix: | (2) |

obtains payoff a when playing another

obtains payoff a when playing another  player, but payoff b when playing a

player, but payoff b when playing a  player. Likewise, strategy

player. Likewise, strategy  obtains payoff c when playing an

obtains payoff c when playing an  player and payoff d when playing a

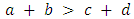

player and payoff d when playing a  player.1. If

player.1. If  and

and  , then

, then  dominates

dominates  . In this case, it is always better to use strategy

. In this case, it is always better to use strategy  . The expected payoff of

. The expected payoff of  players is greater than that of

players is greater than that of  players for any composition of a well-mixed population.

players for any composition of a well-mixed population.  is an unbeatable strategy in the sense of. If instead

is an unbeatable strategy in the sense of. If instead  and

and  , then

, then  dominates

dominates  and we have exactly the reverse situation .2. If

and we have exactly the reverse situation .2. If  and

and  , then both strategies are best replies to themselves, which leads to a ‘coordination game’. In a population where most players use

, then both strategies are best replies to themselves, which leads to a ‘coordination game’. In a population where most players use  , it is best to use

, it is best to use  . In a population where most players use

. In a population where most players use  , it is best to use

, it is best to use  . A coordination game leads to bi-stability: both strategies are stable against invasion by the other strategy.3. If

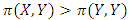

. A coordination game leads to bi-stability: both strategies are stable against invasion by the other strategy.3. If  and

and  , then both strategies are best replies to each other, 4. If

, then both strategies are best replies to each other, 4. If  then

then  is risk-dominant (RD). If both strategies are ESS, then the risk dominant strategy has the bigger basin of attraction.5. If

is risk-dominant (RD). If both strategies are ESS, then the risk dominant strategy has the bigger basin of attraction.5. If  then

then  is advantageous (AD).6. If

is advantageous (AD).6. If  then

then  is a strict Nash equilibrium. Likewise, if

is a strict Nash equilibrium. Likewise, if  then

then  is a strict Nash equilibrium. A strategy which is a strict Nash equilibrium is always an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) ([9], [23]).

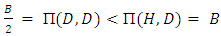

is a strict Nash equilibrium. A strategy which is a strict Nash equilibrium is always an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) ([9], [23]).2.3. ESS and Nash Equilibrium of the Hawk-Dove Game

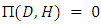

- Recall the Hawk-Dove game, Clearly, Dove is no stable strategy, since

, a population of doves can be invaded by hawks. Because of

, a population of doves can be invaded by hawks. Because of  and

and  , H is an ESS if

, H is an ESS if  . But what if

. But what if  ? Neither H nor D is an ESS. But we could ask: What would happen to a population of individuals which are able to play mixed strategies? Maybe there exists a mixed strategy which is evolutionary stable.Consider a population consisting of a species, which is able to play a mixed strategy, i.e. sometimes Hawk and sometimes Dove with probabilities

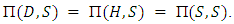

? Neither H nor D is an ESS. But we could ask: What would happen to a population of individuals which are able to play mixed strategies? Maybe there exists a mixed strategy which is evolutionary stable.Consider a population consisting of a species, which is able to play a mixed strategy, i.e. sometimes Hawk and sometimes Dove with probabilities  and

and  respectively. For a mixed ESS S to exist the following must hold:

respectively. For a mixed ESS S to exist the following must hold: Suppose that there exists an ESS in which H and D, which are played with positive probability, have different payoffs. Then it is worthwhile for the player to increase the weight given to the strategy with the highest payoff since this will increase expected utility. But this means that the original mixed strategy was not a best response and hence not part of an ESS, which is a contradiction. Therefore, it must be that in an ESS all strategies with positive probability yield the same payoff. Thus:

Suppose that there exists an ESS in which H and D, which are played with positive probability, have different payoffs. Then it is worthwhile for the player to increase the weight given to the strategy with the highest payoff since this will increase expected utility. But this means that the original mixed strategy was not a best response and hence not part of an ESS, which is a contradiction. Therefore, it must be that in an ESS all strategies with positive probability yield the same payoff. Thus: Thus a mixed strategy with a probability

Thus a mixed strategy with a probability  of playing Hawk and a probability

of playing Hawk and a probability  of playing Dove is evolutionary stable, i.e. that it cannot be invaded by players playing one of the pure strategies Hawk or Dove.To find the Nash equilibrium point of this game, Let

of playing Dove is evolutionary stable, i.e. that it cannot be invaded by players playing one of the pure strategies Hawk or Dove.To find the Nash equilibrium point of this game, Let  be the probability of playing hawk if you are player 1 and let

be the probability of playing hawk if you are player 1 and let  be the probability of playing hawk if you are player 2. The payoffs to the two players are:

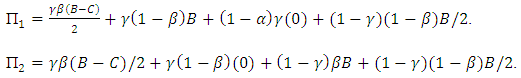

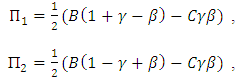

be the probability of playing hawk if you are player 2. The payoffs to the two players are: Which simplifies to

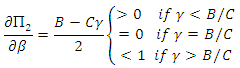

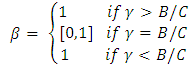

Which simplifies to  Thus

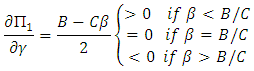

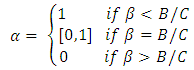

Thus  So the optimal

So the optimal  is given by

is given by Similarly,

Similarly, So the optimal

So the optimal  is given by

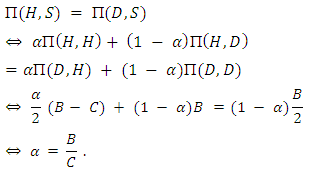

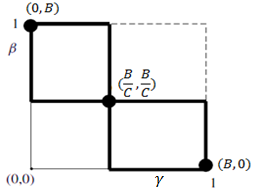

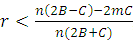

is given by This gives the diagram depicted in Figure 1. The best response functions intersect in three places, each of which is a Nash equilibrium. However, the only symmetric Nash equilibrium, in which the players cannot condition their moves on whether they are player 1 or player 2, is the mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium

This gives the diagram depicted in Figure 1. The best response functions intersect in three places, each of which is a Nash equilibrium. However, the only symmetric Nash equilibrium, in which the players cannot condition their moves on whether they are player 1 or player 2, is the mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium  .

. | Figure 1. Nash equilibria in the Hawk-Dove Game |

3. Hawk-Dove Game among Kin Selection

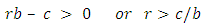

- Kinship theory is based on the commonly observed cooperative behaviors such as altruism exhibited by parents toward their children, nepotism in human societies, etc. Such behaviors toward one’s kin not only decrease the individual fitness of the donor (while benefiting the fitness of others), they often incur costs – thereby decreasing personal fitness.Hamilton’s rule of relatedness provides the foundation of much of the work on kinship theory. This rule states that altruism (or less aggression) is favored when the following inequality holds:

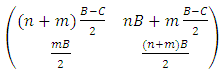

where r is the genetic relatedness of two interacting agents, b is the fitness benefit to the beneficiary, and c is the fitness cost to the altruist. This rule suggests that agents should show more altruism and less aggression toward closer kin ([21]). A simple way to study games between relatives was proposed by Maynard Smith for the Hawk- Dove game . In this section, we will study the Hawk-Dove game in which there is e relationship between the players. Consider a population where the average relatedness between players is given by r, which is a number between 0 and 1. There are two possible methods to study the games between relatives. The "inclusive fitness " method adds to the payoff of a player r times the payoff to his co-player. The personal fitness method, proposed by Grafen ([28]) modifies the fitness of the player by allowing for the fact that a player is more likely than other players of the population to meet co-player adopting the same strategy as himself. We regard the inclusive fitness method to study the Hawk-Dove game ([16] , [10] , [26]). If we assume that there is a relationship between the players, then by using the inclusive fitness method, the payoff matrix of the Hawk-Dove game is given by:

where r is the genetic relatedness of two interacting agents, b is the fitness benefit to the beneficiary, and c is the fitness cost to the altruist. This rule suggests that agents should show more altruism and less aggression toward closer kin ([21]). A simple way to study games between relatives was proposed by Maynard Smith for the Hawk- Dove game . In this section, we will study the Hawk-Dove game in which there is e relationship between the players. Consider a population where the average relatedness between players is given by r, which is a number between 0 and 1. There are two possible methods to study the games between relatives. The "inclusive fitness " method adds to the payoff of a player r times the payoff to his co-player. The personal fitness method, proposed by Grafen ([28]) modifies the fitness of the player by allowing for the fact that a player is more likely than other players of the population to meet co-player adopting the same strategy as himself. We regard the inclusive fitness method to study the Hawk-Dove game ([16] , [10] , [26]). If we assume that there is a relationship between the players, then by using the inclusive fitness method, the payoff matrix of the Hawk-Dove game is given by: | (3) |

Implies to

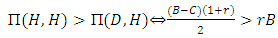

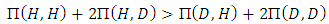

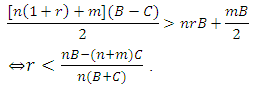

Implies to  .● Hawk’player will be risk-dominant (RD) whenever

.● Hawk’player will be risk-dominant (RD) whenever

Implies to

Implies to ● Hawk’playerwill be advantageous (AD) if:

● Hawk’playerwill be advantageous (AD) if: i.e. if:

i.e. if: Implies to

Implies to

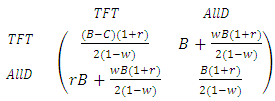

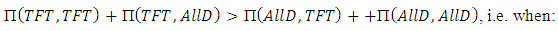

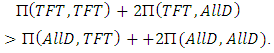

4. Hawk-dove Game among Direct Reciprocity

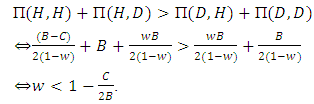

- Direct reciprocity is considered to be a powerful mechanism for the evolution of cooperation, and it is generally assumed that it can lead to high levels of cooperation. Direct reciprocity has been studied by many authors ([25], [6]). Direct reciprocity is based on the idea ‘I help you and you help me’. In every round the two players must choose between cooperation and defection (fight of give way). With probability w there is another round. With probability

the game is over. Consequently, the average number of interactions between two individuals is

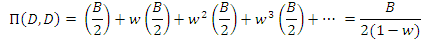

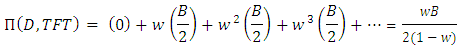

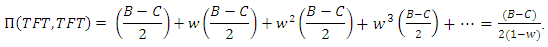

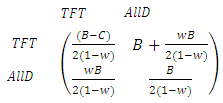

the game is over. Consequently, the average number of interactions between two individuals is  .In order to determine a fundamental condition for the evolution of cooperation in the repeated Hawk-Dove game, we can study the interaction between the dove who play with a strategy ‘always-defect’ (AllD) (i.e. Always cooperate and give away ) and the hawk who play with a strategy Tit -For- Tat (TFT). TFT starts with cooperation and then does whatever the opponent has done in the past move. On the off chance that two hawks (i.e. defectors) meet, they defect constantly. If two doves meet, they cooperate and give away all the time, so:

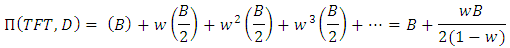

.In order to determine a fundamental condition for the evolution of cooperation in the repeated Hawk-Dove game, we can study the interaction between the dove who play with a strategy ‘always-defect’ (AllD) (i.e. Always cooperate and give away ) and the hawk who play with a strategy Tit -For- Tat (TFT). TFT starts with cooperation and then does whatever the opponent has done in the past move. On the off chance that two hawks (i.e. defectors) meet, they defect constantly. If two doves meet, they cooperate and give away all the time, so: If a hawk meets a dove, the TFT’player fighting in the first round and give away a short time later, while the AllD’player gives away in every round, so:

If a hawk meets a dove, the TFT’player fighting in the first round and give away a short time later, while the AllD’player gives away in every round, so: While, the AllD’player will get

While, the AllD’player will get And the two TFT’players will fight in all the interactions, so:

And the two TFT’players will fight in all the interactions, so: Thus, the payoff matrix is given by:

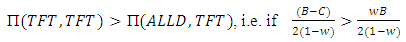

Thus, the payoff matrix is given by: | (4) |

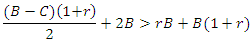

Implies to

Implies to  | (4.1) |

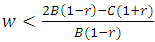

● Fighting will be advantageous (AD) if:

● Fighting will be advantageous (AD) if:

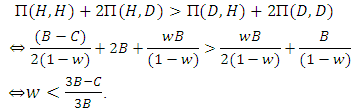

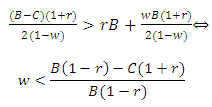

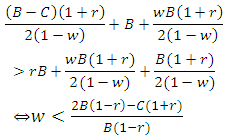

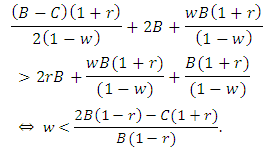

4.1. Direct Reciprocity with Kin Selection in Hawk-Dove Game

- We will now consider that individuals use direct reciprocity with their relatives. One of the simplest strategies of direct reciprocity is Tit-For-Tat (TFT). We will consider that all the hawks are using TFT strategy while the doves are using AllD. Then, the payoff matrix is given by:

| (5) |

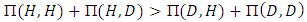

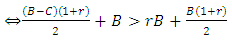

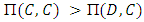

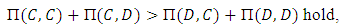

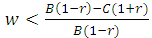

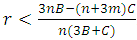

● The fighting will be risk-dominant (RD) if

● The fighting will be risk-dominant (RD) if

● TFT’player has advantageous (AD) if:

● TFT’player has advantageous (AD) if: i.e. whenever

i.e. whenever

5. Group Selection among the Hawk-Dove Game

- Selection does not only act on individuals, but also on groups. A group of cooperators might be more successful than a group of defectors. There have been many theoretical and empirical studies of group selection with some controversy, and most recently there is a Renaissance of such ideas under the heading of ‘multi-level selection’ ([5], [15], [24]).A simple model of group selection works as follows: A population is subdivided into m groups. The maximum size of a group is n. Individuals interact with others in the same group according to a Hawk-Dove game. The payoff matrix that describes the interactions between individuals of the same group is given by:

| (6) |

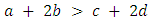

, while the groups which give away have a constant payoff

, while the groups which give away have a constant payoff  . Hence, in a sense between groups the game can take the form as follows:

. Hence, in a sense between groups the game can take the form as follows: | (7) |

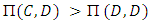

| (8) |

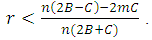

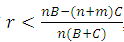

and hawks will invade doves if

and hawks will invade doves if  . If

. If  and

and  respectively. Hawks are RD if

respectively. Hawks are RD if  and will be AD if

and will be AD if  .

.5.1. Group Selection with Kin Selection in Hawk-Dove Game

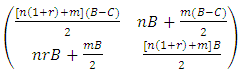

- We will now consider that there is a relationship between players in the same group, using the Hawk-Dove game, then the payoff matrix is given by :

| (9) |

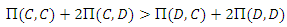

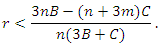

● The fighting between relatives in the same group will be (RD) if the inequality:

● The fighting between relatives in the same group will be (RD) if the inequality: Implies to

Implies to  ● Also the fighting between relatives will be (AD) if:

● Also the fighting between relatives will be (AD) if: i.e. when

i.e. when Therefore, group and kin selection together can evolve strong fighting than either of them working alone, especially when average relatedness is low, groups are large and the number of groups is small.

Therefore, group and kin selection together can evolve strong fighting than either of them working alone, especially when average relatedness is low, groups are large and the number of groups is small.6. Conclusions

- Direct reciprocity can lead to the evolution of cooperative behavior (give way) but if it works together with kin selection it can lead to a strong cooperation between players . We found that, the necessary condition for evolution of cooperative behavior is:

, the population of cooperators will be RD if:

, the population of cooperators will be RD if:  . Where r is the average relatedness between individuals , which is a number between 0 and 1, and w is the probability of next round.When the group selection works with kin selection, then our fundamental conditions, that we derived , showed that fighting can be maintained in the population, even when the average relatedness is low, groups are large and even if the benefits of fighting are low, if

. Where r is the average relatedness between individuals , which is a number between 0 and 1, and w is the probability of next round.When the group selection works with kin selection, then our fundamental conditions, that we derived , showed that fighting can be maintained in the population, even when the average relatedness is low, groups are large and even if the benefits of fighting are low, if  , fighting between players can emerge, otherwise the cooperation (give way) behavior will be maintain in this situation. Hawks strategy will be risk-dominant (RD) whenever

, fighting between players can emerge, otherwise the cooperation (give way) behavior will be maintain in this situation. Hawks strategy will be risk-dominant (RD) whenever  , and will be advantageous (AD) if

, and will be advantageous (AD) if  .For cooperation (give way) to prove stable, the future must have a sufficiently large shadow. An indefinite number of interactions, therefore, is a condition under which cooperation (give way) can emerge.

.For cooperation (give way) to prove stable, the future must have a sufficiently large shadow. An indefinite number of interactions, therefore, is a condition under which cooperation (give way) can emerge. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML