-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Game Theory

p-ISSN: 2325-0046 e-ISSN: 2325-0054

2015; 4(2): 26-35

doi:10.5923/j.jgt.20150402.02

Energy Challenges for Europe – Scenarios of the Importance of Natural Gas Prices from a Game Theory Perspective

Maria-Floriana Popescu, Gheorghe Hurduzeu

Faculty of International Business and Economics, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

Correspondence to: Maria-Floriana Popescu, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Europe is an important energy consumer and is permanently searching to overcome the challenges that arise while addressing its energy needs. The fast growing demand and competition for energy resources (especially from emerging countries such as India or China), the never-ending conflicts that are taking place in the energy producing areas (e.g. the Arab spring or the Israel-Gaza fights), the fragmented internal market of the European Union aiming for liberalisation, the heavy reliance (more than 30 percent of the gas imports) on the Russian gas and a greater significance given to reducing carbon emissions are only a few of the challenges that are on the European list of priorities that have to be resolved for a better future. As a result, providing affordable energy, improving energy efficiency and reducing emissions are key topics of the European agenda and clever moves on the great world chessboard that are worthy to be considered and analysed. Therefore, this research paper aims to simulate various scenarios on different approaches that Europe might employ in terms of energy and related to the evolution of natural gas prices from a game theory perspective, studying various strategic interactions and their potential outcome for Europe’s future. The methodology used in this paper to have a game theory approach on the evolution of European Union’s imports of fuels is based on a literature review and the study of important reports from this field. Non-cooperative and cooperative scenarios are built in the “Game theory approach” section of this research paper and are meant to describe various situations that could arise in the future and how could Europe respond to them. The “Conclusions” restate the need of the European Union to lower their imports from Russia and the solutions for choosing better alternatives to the Russian natural gas.

Keywords: Energy, Game theory, Cooperation, Russian natural gas dependency

Cite this paper: Maria-Floriana Popescu, Gheorghe Hurduzeu, Energy Challenges for Europe – Scenarios of the Importance of Natural Gas Prices from a Game Theory Perspective, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2015, pp. 26-35. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20150402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Modern societies cannot function properly without energy, a good that is necessary for life and the development of all economic activities. As the disruptions in energy availability may lead to severe and unrelenting consequences that might affect a wide range of industries and societies, the energy encompass all the characteristics of an essential good, as there is a strong correlation between economic growth and energy consumption – one percentage point of economic growth can lead to a growth of 0.5% of primary energy consumption [1]. Therefore, the importance energy has in an economy places it in the centre of political interests. As a rising need as energy emerges all over the world and the climate change has become an issue of high importance for every nation around the globe, all the energy-related issues and the energy policy gain in importance and attract scientific and media attention. But in Europe, the focus is more significant as European Union’s (EU) Member States are among the most industrialised regions, and the social and economic welfare are top ranked in the world. The demand for energy in Europe is in a continuous growth, as well as the evolution of industry and the increase of population, and there is a scarcity in fulfilling the domestic demand by using its own energy resources. Therefore, the European Union is forced to import most of its energy in order to provide the needed amount requested by consumers. For many years, the supply comes from the Soviet Union (in the past) / the Russian Federation (now). Consequently, the relationship between Russia and the EU has to be beneficial for both partners as to maintain a proper supply of energy on the European market, or, if the relations cannot be held amiable anymore, other trade partners have to be found for both regions. Being given the crucial nature of these relations, policy agendas from all over the world have started to include this subject, and, over the last years, public debates in the energy field are held more frequently, without forgetting to take into account in these discussions the fluctuations of prices imposed by Russia to major transit countries. Public and scientific debate leave the careful observer unsatisfied, as distortions, accusations and one-sidedness dominate these discourses [2]. The climate that is therefore built is not beneficial for agreements or for resolving potential conflicts that might emerge. Every part involved in these relationships has personal interests as well and is aiming to obtain the maximum gain with minimum costs and efforts. The European Union was envisioning of integrating the national energy markets until 2014, along with providing consumers and businesses with a wider range of qualitative products and services, along with a fruitful and honest competition, through a secured supply of energy. Even though not all these goals were attained until now, progresses have been made, such as the possibility of consumers to select their provider of gas and electricity. There are still things that have to be done such as aligning national markets and network operation rules for gas and electricity along with supporting cross-border investments done in energy infrastructure. This paper studies in detail the current situation that exists in the European Union in terms of energy consumption and production, especially natural gas related, focusing on presenting the relationship between Russia and the EU regarding the trade of energy. One of the main contributions of this paper is the analysis of the existing dependency between Russia and the European Union from a game theory perspective applied in order to predict future behaviours of the participants, being given the “game” and the “players”.

2. Context and Background

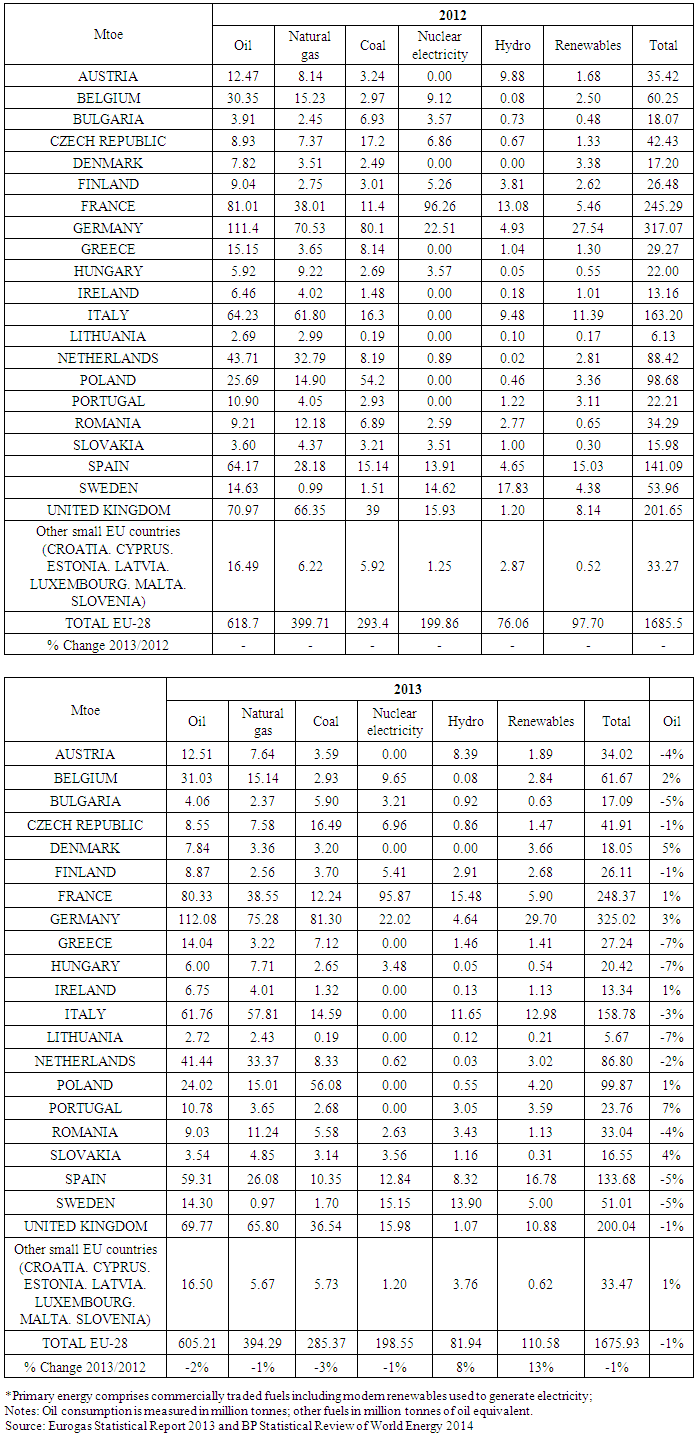

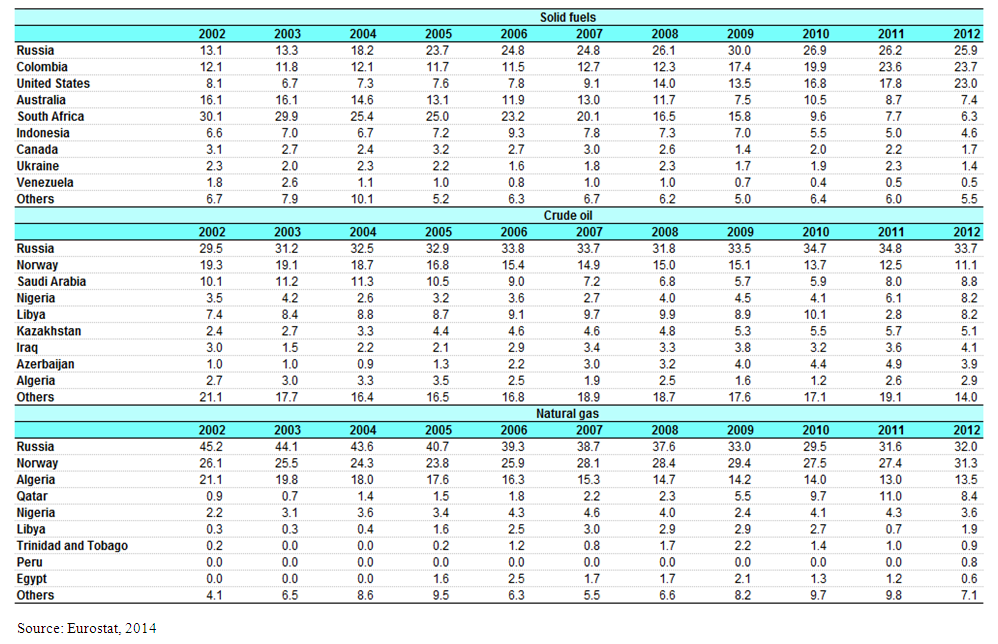

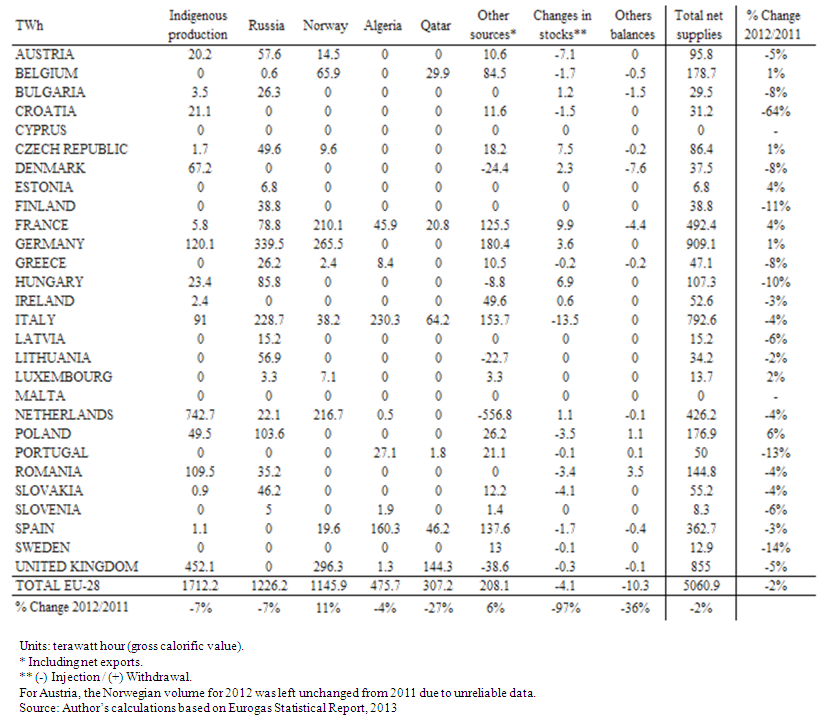

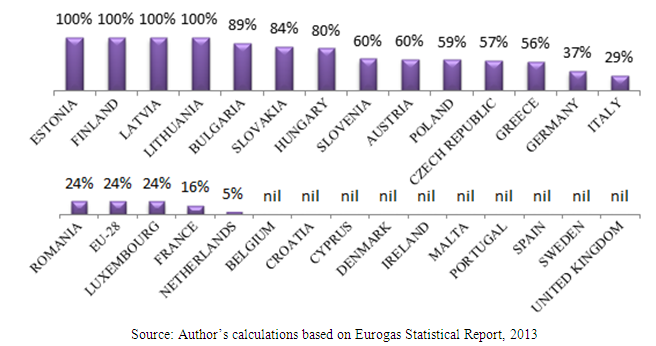

- The 28 Member States of the EU are experiencing for decades a continuous growth in natural gas consumption and imports, while EU’s power of production of natural gas has declined and the dependency of imported natural gas has increased. Therefore, the dependency on its primary supplier of natural gas, Russia, has increased and the imports have started to be influenced by political means, and not by the economic forces. Unlike oil, that is considered to be a global commodity rather than a regional one, natural gas has a regional importance with local buyers and sellers that have gained power in exercising influence over the price and quantity of natural gas produced and sold. An analysis of the final energy consumption (Table 1), without taking into account the energy used by power producers and the one lost in the transformation processes, of the 28 Member States within the European Union, had registered values under two thirds, 65.6% respectively, of gross inland consumption, with values of 1,685.50 million toe in 2012 and 1,675.93 million toe in 2013, concluding in a change of -0.57% between the consumption from 2013 compared with the measurements from 2012. The relative shares of the four largest EU Member States (France, Germany, Italy and United Kingdom) accounted for 55.01% in 2012 and 55.66% in 2013 of the EU-28’s gross inland consumption. Between them, for both years, Germany had the highest share, with 18.81%, 19.39% respectively. France (14.55% in 2012 and 14.81% in 2013) and the United Kingdom (11.96% in 2012 and 11.93% in 2013) were the only two other member states that recorded double-digit shares, while Italy’s share was just below this level (9.68% in 2012 and 9.47% in 2013).

|

| Figure 1. Natural gas major trade movements, 2013 (billion cubic metres) |

| Figure 2. Global gas reserves by region, 2013 |

| Table 2. Main origin of primary energy imports, EU-28, 2002–2012 (% of extra EU-28 imports) |

| Table 3. Natural gas supplies in the EU-28, 2012 |

| Figure 3. Gas supplied by Russia, % of total, 2012 |

3. Game Theory Approach

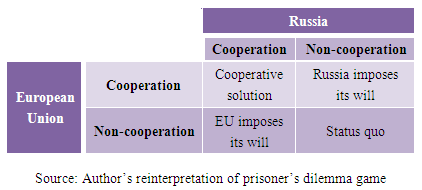

- Game theory is defined by Arsenyan as a branch of mathematics that explores the aspects of conflict and collaboration arising among companies or “players” [12]. Moreover, it is “the study of mathematical models of conflict and cooperation between intelligent rational decision-makers” [13].As any model used to understand better a problem and its consequences, there are limitations that have to be taken into consideration. Many game theory applications require that decision makers are rational. That is, they have clear preferences, form expectations about unknowns, and make decisions that are consistent with these preferences and expectations [14]. In the situations that are described in this paper, the countries are assumed to be key players in the game. Therefore, they are presumed to have clear preferences, based especially on the aggregate welfare of their citizens. But, in reality, the citizens have different and various preferences and the decisions are taken especially based on political means. From a game theory perspective, there are four basic scenarios for the development that will tackle the future of the EU-Russian energy relationship. Therefore, from the classical example of a game theory approach, the prisoner’s dilemma, where players choose to opt for a cooperative or non-cooperative option, exemplifies the situation where the outcome of the game is dependent not only by a particular strategy but also on the nature of the other actors’ action plans. The non-cooperative outcome refers to a situation where the strategy imposed by one partner determines the other to adapt and run a cooperative plan. The prosecution of non-cooperative strategies lead to a status quo outcome, where both regions opt to maintain the current state of things. In this case, it might lead to a deterioration of current relations due to an energy security dilemma [15]. A mutually beneficial outcome can be reached only if both parties adopt a cooperative strategy as can be seen in Figure 4.

| Figure 4. European Union – Russia energy related relations in a prisoner’s dilemma matrix |

3.1. Non-Cooperative Games

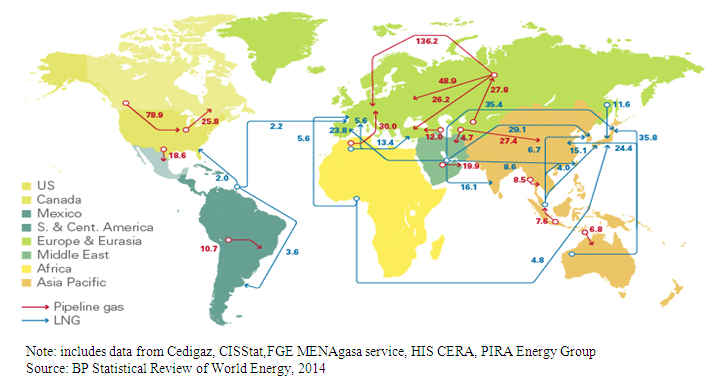

- In non-cooperative games, players make decisions independently, and these decisions will be illustrated with examples relevant to Europe’s energy sector and the relationship with Russia. The possibility of more tensioned relations between Russia and the EU may arise, leading to two main possible scenarios presented hereinafter. A first situation that may appear would involve disruptions in the Ukrainian flow of natural gas, a scenario that would have negative effects on EU’s supply with energy, as Ukraine is the main transit country of the Russian gas. This situation can take place in a moment when gas trade relations between Russia and the EU are working properly but Russia decides to cut the supply or increase the price of the gas delivered to Ukraine, being driven by commercial reasons, since Ukraine imported huge quantities of gas from Russia in 2013, respectively 50.3 billion cubic metres in 2012 [16] and 28 billion cubic metres in 2013 [17]. But, in December 2013, the presidents of the two countries have agreed on a special gas price, down from more than $400 (£245; 291 euros) per 1,000 cubic metres to $268.5 [18]. This measure was intended to ease Ukraine’s financial difficulties at a time when the country was struggling to avoid default, being a part of the rescue package proposed by Russia for macroeconomic stabilisation. However, the revolution that followed this event and the governmental changes that took place in Russia transformed the above action into a promise that was withdrawn. Moreover, in April 2014, the price of natural gas witnessed an increase of more than 80%, being set at $485. As it was mentioned by Gazprom representatives, this action was the consequence of unpaid debts by the Ukrainian part, having been repaid so far only $1,300 [19]. Even if there were taken decisions that were not favourable for Ukraine, the energy relations between Russia and Ukraine have not yet been completely disrupted by the Crimean crisis and Gazprom has proposed a loan for Ukraine in order to continue to pay for its gas imports [20]. But, these singular actions cannot be understood as a permanent behaviour of Russia towards Ukraine, because when the next winter will bring expanded gas needs for Kiev, unforeseeable military escalations might appear as Russian troops are still lingering around the Ukrainian border, and some Eastern Ukrainian cities will be starting to claim their independence, as in Crimea [21]. Also commercial disagreements may arise as in 2006 or 2009 when the Ukrainian crises occurred. If Ukraine remains indebted to Russia, the supply of gas could be hampered and therefore, Ukraine could borrow from the EU, thus affecting the European market. Consequently, this scenario can be avoided if Ukraine reforms its energy sector and make it more transparent due to high levels of corruptions from the gas market [22]. Moreover, diminishing consumption, efficient use of energy and clear regulations of the gas flow, could help avoid disruptions in the Ukrainian flow of natural gas in the future. The second scenario appertaining to non-cooperative games between Russia and the EU consists of general natural gas flow disruptions, being more likely to occur [23, 24]. Military tensions could arise from an invasion of territories occupied by Russian military forces and this could lead to sanctions applied by the European Union. Moreover, limiting the gas flow in various pipelines, such as Nord Stream, could have an impact on many EU countries that are highly dependent, as noted before, of the Russian natural gas. This scenario brings into discussion the quantity of gas that has to be reallocated due to various possible actions, but there is no certainty because in the past years, the quantities of gas imported from Russia have been growing but there is no clear evidence of these as statistics are different depending of the source. For example, for 2013 there are figures calculated by Wood Mackenzie and Gazprom. This year was marked by a difficult winter and terrorist attacks in Algeria that lead to an increased demand and a decreased production, favouring Russian exports [20]. Gazprom states that exports to Europe in 2013 accounted to 161.5 billion cubic metres [11], a large increase compared to 138.8 billion cubic metres in the previous year (in 2011 it was 150 billion cubic metres, so 2012 was characterised by an unusual drop in imports). Wood Mackenzie estimates 155 billion cubic metres, with 53% of this gas shipped via Ukraine, confirming an increase over the previous year [9]. More data can be found on Eurostat but the last referral year is 2012. The LNG imports and prices declined over the last years, but this is explained by the rising Asian competition.European Union’s high dependence on Russia’s natural gas is of such importance and volume that it cannot be counterbalanced from one day to another. Russian gas will witness depreciation in terms of pricing in the long run and it will be accessible because of the pipelines’ overcapacity. The EU has not yet decided its future strategy; a general disruption on the energy market could finally persuade Europe to act and become independent of Russia’s fuels.

3.2. Cooperative Games

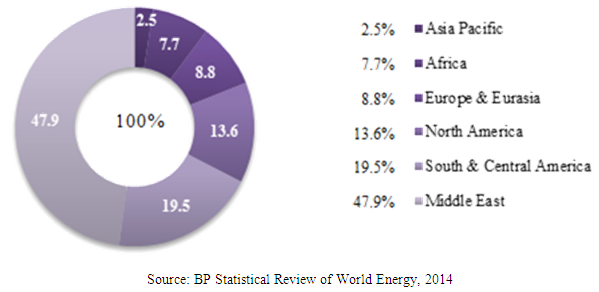

- The game theory literature has witnessed debates on whether a cooperative outcome is more likely to arise from a small or a grand coalition of countries, being given the various relationships that exist among countries from all over the world. Therefore, cooperative game theory investigates situations where coalitions are built by players that aim to enforce a cooperative behaviour. For cooperative games, the outcomes of interest consist of a partition of the players into coalitions, and actions for each coalition. Players in a coalition behave cooperatively with each other, and non-cooperatively with respect to other players and coalitions. The core is a concept that can be used to analyse the stability of a grand coalition of all players [14]. In the context of cooperation, Europe has to benefit from its geopolitical location and from changes in the global natural gas infrastructure. Therefore, EU has to start relying on other sources of energy, as a study conducted by EIA showed that technically recoverable shale gas resources worldwide may exceed current global gas reserves [25]. Moreover, Europe can start being involved in finding alternatives to Russian natural gas such as:• Further investments in increasing the exports of natural gas from North African countries. Following the change in regimes from Libya and Egypt, great opportunities of natural gas production have flourished in the region. Both countries have important reserves of gas but do not have the needed infrastructure to export the fossil fuel; the situation in Egypt was so difficult as in 2012 they started to import natural gas [26]. However, this region imposes threats to energy security, as for example in 2013 Algeria witnessed terrorist attacks and shale gas crisis that showed concerns regarding the largest exporter of natural gas from North Africa and the possibility to transform this country in a continuous supplier of energy for Europe, replacing the role of Russia in the region. • Taking advantage of the great potential for new natural gas supplies the Caspian region holds could be a viable alternative for Europe to Russian gas, but it has to find solutions for transporting this gas into EU without crossing the Russian territory. The Caspian natural gas is using the southern corridor of pipelines to reach Europe, and the transportation is hampered and difficult, therefore the gas is transported in the East rather than West. • An additional alternative to importing natural gas from Russia would be using liquefied natural gas (LNG) as it accounted in 2012 for 18% of the EU’s natural gas imports and 19% of its consumption [27]. The EU LNG regasification capacity has more than doubled in the past five years. Europe has enough LNG import capacity to meet over a third of its annual demand and therefore, enough capacity to meet hard winters with rising demand of energy. Due to periods of underutilisation of the LNG facilities, it is somewhat difficult for the EU to make improvements in this infrastructure, but building pipeline interconnections and managing the import capacity are priorities on the European agenda. • Obtaining LNG from the United States can be another alternative to Russia, taking into account the role of US on the energy market, especially the one of LNG. As most of the proposed US LNG export projects are located on the Gulf Coast or East Coast of the United States, making shipments to Europe will probably be economical, and therefore, Europe can be a good marketplace for the American liquefied natural gas. Therefore, any strategy employed in the European Union would need to be accompanied by dialogue and, preferably, an institutionalised framework. Using a game theory approach aims to inform about the need of participation and compliance in international agreements, the role of coalitions, and the role of dialogue when negotiating over the prices, the quantities and the fuels that are going to be imported.

4. Conclusions

- There could be a moment when European Union would decide to shut down all natural gas pipelines that are coming from Russia and to decline the oil brought on its territory by Russian oil tankers. The rationale behind this idea might be to make Russia understand that Europe is a valuable customer for their fuels and such a decision could affect their economy and stability. But, there will always be enough countries or regions that will be interested in buying the Russian fuels as they are in need of energy. Taking measures to reduce purchases of Russian energy would require European leaders to show both moral courage and an overt willingness to inflict financial pain on large and well-connected companies. But both of these things are in short supply—just like natural gas and oil [28].EU has started to diversify its gas supplies and to find new solutions that could help it cope with a disruption in the natural gas flow. Moreover, new interconnections between various European countries were made, such as building pipelines between Hungary and Croatia, Slovakia or Romania, Austria and Slovenia, or Czech Republic and Poland. “Reverse flow” pumps have also been installed allowing gas to be pumped from West to East. Germany’s RWE and Polish state company PGNiG supplied small volumes of gas to Ukraine last year, and discussions are under way to provide Ukraine with gas from Slovakia as well [29]. Moreover, Europe started to invest more in the LNG technology in hope of replicating the success of the US shale gas boom but progress has been slow and difficult: there were prohibitions of the hydraulic fracturing process in some countries (for example, France and Bulgaria), and problems with the public opposition in countries were the exploit of shale gas reserves was desired (for example, the United Kingdom). Apart from these prohibitions, Poland, that has great shale gas potential, delayed the drilling process due to other numerous problems. All in all, there are solutions for choosing better alternatives to the Russian gas in pursuit of defining and building a sustainable energy policy mix in the European Union, a plan for savings and changes in the energy basket. But for now, with the current energy policies in place, the dependency on Russia, a cheap and well-known gas source, is predicted to grow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This work was cofinanced from the European Social Fund through Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development 2007-2013, project number POSDRU/159/1.5/S/134197 “Performance and excellence in doctoral and postdoctoral research in Romanian economics science domain”.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML