Qing Hu

Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan

Correspondence to: Qing Hu , Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

We analyze the incentive of bundling by considering the effects of quality disclosure for a multiproduct firm. The firm monopolizes one market with a high-quality product but competes with another firm in another market with a new product whose quality is unknown to consumers. We show that the incentive to disclose quality for the firm using a bundling strategy is always stronger than it is for a firm using an independent pricing strategy. Importantly, bundling is never preferred when the level of consumers’ reservation value is relatively small, regardless of the cost to disclose and the real quality of the new product and the competitor’s product. However, as the level of consumers’ reservation value increases, the market can be captured if the multiproduct firm bundles and such bundling ensures its monopoly position and profits.

Keywords:

Bundling, Quality disclosure, Multiproduct firm

Cite this paper: Qing Hu , Bundling and Quality Disclosure in a Bayesian Game, Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 13-17. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20150401.03.

1. Introduction

In modern life, information plays an important role in consumers’ purchasing decisions. Firms always engage in demonstrating the quality of their products if their quality is high. However, demonstrating quality may induce costs. Sometimes, firms may disclose quality strategically. Mostly, bundling is not preferred as a strategy for a multiproduct firm if it has competitors in a certain market (Whinston, 1990). However, if we consider quality disclosure in the context of bundling, the firm may have different strategies concerning quality disclosure under bundling and independent pricing, which may affect bundling incentives. When is the firm willing to disclose quality under both bundling and independent pricing? Which case is the one where the firm is more willing to disclose quality? What about the incentives of bundling in light of the costs to disclose and the effects on strategy? We intend to analyze the incentives of bundling by considering the effects of quality disclosure for a multiproduct firm that monopolizes one market with a high-quality product but competes with another firm in another market with a new product whose quality is unknown to consumers.A significant number of studies have examined bundling. Most of these consider symmetric competition, meaning two multiproduct firms compete by considering bundling as a competitive tool. We can divide such previous work into two categories. The first category is research based on “product-specific preferences,” a term that means consumers differentiate between products sold by a firm. For example, a consumer may have a strong preference for Gucci’s bags but a weak preference for Gucci’s clothing line, while also having a stronger preference for Prada's clothing line. Matutes and Regibeau (1988) made a significant contribution to the literature on this kind of bundling problem. They examined the incentive of pure bundling for two symmetric, multiproduct firms by building a two-dimensional Hotelling unit square. They found “pure bundling” was always dominated as a strategy by “pure component” or “independent pricing” regardless of the level of consumer reservation value. Gans and King (2006) extended Matutes and Regibeau’s (1992) model to analyze the incentives associated with mixed bundling. The other category is based on “firm-specific preferences,” a term that means products sold are not differentiated but the firms are differentiated for consumers. For example, a consumer will pay less in transportation fees when he buys two products from one supermarket compared to purchasing one product from one supermarket and the other from another supermarket. Therefore, the term “firm specific preferences” captures the reduced cost if a consumer purchases products from one firm rather than two. However, such cost reduction does not occur in the case of product-specific preferences. Thanassoulis (2007) and Armstrong and Vickers (2006) are representative of this research. Thanassoulis (2007), in particular, provided a model on a Hotelling unit interval in a fully served market. He examined the incentives of mixed bundling for two symmetric, multiproduct firms, and he compared the situations of firm-specific and product-specific preferences. Armstrong and Vickers (2006) analyzed the case of mixed bundling by integrating product-specific with firm-specific preferences on a two-dimensional square in a fully served market. In this study, we build a model under firm-specific preferences using graphics.Levin (2009) showed an important method of ascertaining the answer to the problem of quality disclosure. He built a Hotelling model with two symmetric firms selling an identical product, for which consumers display specific taste and quality preferences. He found a threshold point where firms are indifferent between disclosing and not disclosing the real quality of their products. In this study, we analyze quality disclosure by extending the model of Levin (2009). Choi (2003) discussed the information leverage effect of bundling for a multiproduct monopolist where the quality of one product is high and that of the other is unknown. He found that the advantage of high quality for product 1 could be extended to the unknown product by bundling. However, in our study, we find that there is no such information leverage effect associated with bundling.The remainder of this study is arranged as follows. In section 2, we introduce the model, and in section 3, we present our conclusions.

2. The Model

Firm A sells product 1, and it launches a new product, product 2, which is identical to a product sold by firm B. Firm A can sell products using either pure bundling or independent pricing. We assume the marginal cost of either product for both firms is zero. Consumers purchase at most one unit of each product. Consumers’ preferences depend on “firm” and “quality.” “Firm” stands for “firm-specific preferences,” which means that the products they sell are not differentiated, but the firms themselves are differentiated. Thus, consumers are uniformly distributed along a Hotelling unit interval with a length of 1. Firm A is located on the left corner, and firm B is located on the right corner. If firm A sells products separately under an independent pricing strategy, a consumer located at a certain distance d1 away from firm A who buys two products from two firms will obtain a surplus of 2C + q1A + q2B - μ × 1 - p1A - p2B. The term C represents the reservation value for a consumer to purchase a certain product. The term qmj, m = 1, 2, j = A, B represents the quality of a certain product, and qmj ∊ [0, 1]. The term pmj, m = 1, 2, j = A, B is the price of a certain product. The term μ is the strength parameter of differentiation. Importantly, this consumer is d1 away from firm A and 1 - d1 away from firm B. Thus, purchasing two products from two firms induces a cost μ × 1. However, if this consumer purchases both products from firm A, he will obtain a surplus of 2C + q1A + q2A - μ1d1 - p1A - p2A, where μ ≤ μ1 ≤ 2μ, meaning he benefits from a reduced cost owing to one-stop shopping. The reduced cost may stand for a repeated contract cost, cost of collecting information, or transportation cost. Therefore, for the case of pure bundling, a consumer located d1 away from firm A purchasing a bundle from firm A will obtain a surplus of 2C + q1A + q2A - μ1d1 - pA, where pA is the bundle price.We describe several assumptions we make here. We assume consumers know the quality of firm A’s product 1 is high, q1A = 1, and they know the quality of firm B’s product 2 to be q2B ∊ [0, 1]. However, consumers do not know the quality of firm A’s new product 2, but q2A is randomly distributed over [0, 1]. Then, we set C > 1, which guarantees that in the equilibrium, the market is fully served and consumers are always able to buy two products together regardless of the level of q2A and q2B when firm A does not engage in pure bundling. This situation is close to reality. For simplicity of calculation, we set μ = 1, μ1 = 1.5.We examine a three-stage game. At the first stage, firm A decides whether to bundle (B) or not (I). At the second stage, firm A observes its q2A and decides whether to disclose quality. If it discloses the real q2A, the cost of disclosing (δ) comes into effect. At stage 3, both firms set prices simultaneously. The solution is a Perfect Bayesian equilibrium, and we follow the basic idea of Levin (2009) to solve for disclosure strategies and consumers’ beliefs about q2A in equilibrium. There is no signaling role for prices here.In the Perfect Bayesian equilibrium, there is q2A*B and q2A*I, representing a threshold where firm A engages in pure bundling and independent pricing, respectively. Firm A discloses q2A if and only if real q2A R > q2A*, and the disclosed quality is the real quality. The cost of disclosing is denoted as δ. If firm A does not disclose, the perceived quality q2A is uniformly distributed over [0, q2A*], so that the perceived q2A = q2A*/2.

2.1. Stage 3

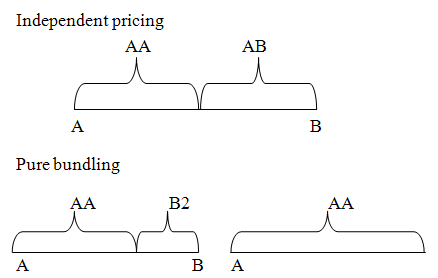

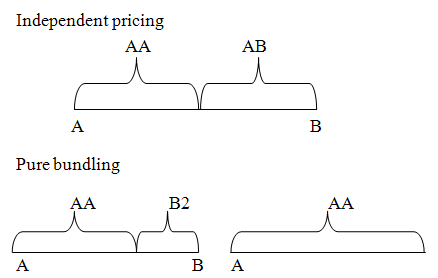

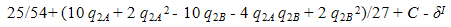

The market configurations when firm A engages in independent pricing and pure bundling are shown in Figure 1. | Figure 1. Market configurations |

AA means buying two products together from firm A; AB means buying two products from the two firms; and B2 means buying only product 2 from firm B. Two market configurations are possible when firm A bundles. As consumers’ reservation value increases, firm B is kicked out of the market since the reduced cost of one-stop shopping is attractive for consumers when they are able to purchase two products together. However, if firm A does not bundle, firm B never leaves the market.

2.1.1. Independent Pricing

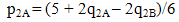

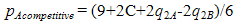

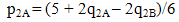

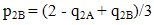

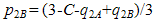

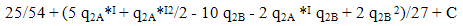

If firm A engages in independent pricing, there is a consumer located at point x*, who is indifferent between buying AA and AB, so that 2C + q1A + q2A - p1A - p2A - μ1x* = 2C + q1A + q2B - p1A - p2B – μ × 1, product 1 is not in this function; then, we can obtain x*= (2 - 2 p2A + 2 p2B + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/3. Then, the profit of A2 and B2 are given as follows:πA2 = p2A x* = p2A (2 - 2 p2A + 2 p2B + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/3πB2 = p2B (1 - x*) = p2B (1 - (2 - 2 p2A + 2 p2B + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/3)We differentiate the profit of each firm by p2A and p2B, respectively, and maximize the profits. Then, we obtain  | (1) |

| (2) |

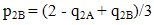

All consumers can buy product 1. Therefore, firm A sets p1A, so that C + q1A - p1A - μ × 1 = 0, and thus, | (3) |

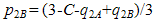

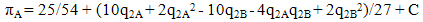

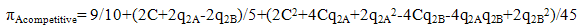

Then, the profit function of firm A when it engages in independent pricing is given as follows: | (4) |

2.1.2. Bundling

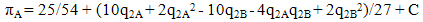

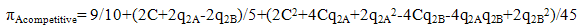

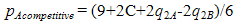

We can also derive the profit of firm A if it bundles. Because there are two market configurations when firm A bundles, we discuss them separately. First, when firm B still exists, a consumer located at the point x* exists, who is indifferent between buying AA and B2, so that 2C + q1A + q2A - pA - μ1x* = C + q2B - p2B – μ (1 - x*), and thus, we obtain x* = (4 + 2C + 2 p2B - 2 pA + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/5. The profit functions of firms A and B are respectively given as follows:πA = pA X* = pA (4 + 2C + 2 p2B - 2 pA + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/5πB= p2B (1 - X*) = p2B (1 - (4 + 2C + 2 p2B - 2 pA + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/5) (9 + 2C + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/6We differentiate each firm’s profit by pA and p2B, respectively, and maximize the profits. Then, we obtain  | (5) |

| (6) |

We find that the price of the bundle pA competitive increases as C increases, but p2B decreases as C increases. Then, we can obtain the maximized profit of firm A: | (7) |

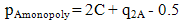

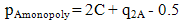

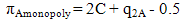

Second, as C increases, consumers benefit from buying two goods from firm A based on one-stop shopping. Firm B has to set its price low enough and close to zero. Thus, it leaves the market. At this time, firm A acts as a monopoly and it sets pAmonopoly, so that 2C + q1A + q2A - pAmonopoly - μ1 × 1 = 0, and thus,  | (8) |

| (9) |

This leads us to our first proposition.Proposition 1: If firm B is always in the market, p2AI + p1AI > pAB competitive. If firm B leaves the market when firm A bundles, then p2AI + p1AI< pAB competitive.We can prove this proposition easily. For a market where firm B is still in the market, if firm A bundles, p2AI + p1AI = (5 + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/6 + C, pAB competitive = (9 + 2C + 2 q2A - 2 q2B)/6, and pAB competitive - (p2AI + p1AI) = 2/3 - 2C/3. Because C > 1, pAB competitive - (p2AI + p1AI) < 0. We obtain p2AI + p1AI > pAB competitive. This means that the bundle price is lower than the total price of the two products sold under independent pricing. Moreover, as C increases, the price gap widens owing to increase in the intensity of price competition when firm A bundles. For a market where firm A is a monopolist, pA monopoly - (p2AI + p1AI) > 0 always, and this shows the concept of a monopoly market.

2.2. Stage 2

In this section, we determine the threshold quality of A2 under independent pricing and pure bundling.

2.2.1. Independent Pricing

There is a threshold q2A*I. Firm A discloses q2A if and only if the real q2A > q2A*I, and the disclosed quality is the real quality. The cost of disclosing is denoted as δ. If firm A does not disclose, perceived quality is uniformly distributed over [0, q2A*I], so that the perceived quality is q2A = q2A*I/2. Therefore, if firm A discloses, the expected profit is given as follows:  | (10) |

If firm A does not disclose quality, the expected profit is given by  | (11) |

To derive q2A*I, let (10) and (11) be equal and q2A = q2A*I; then, we obtain q2A*I = (-5 + 2 q2B + (25 - 20 q2B + 4 q2B 2 +162δI) 1/2)/3. For the existence of q2A*I, q2A*I must be smaller than 1. If we set q2B = 1, q2A*I = (-3 + (9 + 162δI) 1/2)/3 and δI < 1/6. If δI > 1/6, we set q2A*I = 1, and in this situation, firm A never discloses.

2.2.2. Pure Bundling

First, when firm B is always in the market, we derive the threshold under this situation by the same method used above, and we can obtain q2A*Bcompetitive = (-18 - 4C + 4 q2B + ((18 + 4C - 4 q2B) 2 + 1080δ) 1/2)/6. If we set q2B = 1, q2A*Bcompetitive = (-14 - 4C + ((14 + 4C) 2 + 1080δ) 1/2)/6 and δBcompetitive < (17 + 4C)/90. Second, when firm B has left the market, we obtain δBmonopoly < 1/2 always, and q2A*Bmonopoly = 2δ.This leads us to our second proposition.Proposition 2: Regardless of the level of C and q2B, the incentive to disclose quality for firm A under bundling is always stronger than it is under independent pricing.We can easily see the existence of the threshold of q2A*. For example, when q2B = 1 and C = 1.5, we have δI < 1/6, δBcompetitive < 23/90, and we obtain 23/90 > 1/6. If C = 4, firm B has left the market, δI < 1/6, δBmonopoly < 1/2, and we also obtain 1/2 > 1/6. This relationship does not change as the level of C and q2B change. Under independent pricing, firm A discloses only if the cost to disclose is small enough compared to the situation under pure bundling. This means that the incentive to disclose quality for firm A under bundling is stronger than it is under independent pricing, regardless of whether firm B leaves the market.

2.3. Stage 1

In this section, we identify the incentives for firm A to bundle. Our third proposition is as follows. Proposition 3: Regardless of q2B, real q2A R, and the real cost to disclose δ, if firm B is always in the market, independent pricing always dominates pure bundling for firm A. However, if firm B leaves the market when firm A bundles, pure bundling is always the dominant strategy and ensures a monopoly position.We can prove this proposition easily. First, we discuss the problem where firm B competes with firm A even though firm A bundles. We give an example by setting q2B = 1, C = 1.5. For the existence of the threshold of q2A, we have δI < 0.17 and δBcompetitive < 0.26. Then, we examine different situations as follows:For δ < 0.17, we assume δ = 0.1, q2A *I = 0.67, q2A *Bcompetitive = 0.42.If q2A R < 0.42, neither discloses and πABcompetitive < πAI.If 0.42 < q2A R < 0.67, firm A discloses only when it bundles and πABcompetitive<πAI.If q2A R > 0.67, both firms disclose and πABcompetitive < πAI.For 0.17 < δ < 0.26, we assume δ = 0.22, q2A *I = 1, q2A *Bcompetitive = 0.88.If q2A R < 0.88, neither discloses and πABcompetitive < πAI.If q2A R > 0.88, firm A discloses only when it bundles and πABcompetitive < πAI.For δ > 0.26, q2A *I = 1, q2A *Bcompetitive = 1, neither discloses and πABcompetitive < πAI.Then, we find that, if firm B left the market, when firm A bundles πABmonopoly > πAI always.If firm B competes with firm A, the competition under bundling is fiercer, and thus, independent pricing is more profitable for firm A. However, as C increases, more and more consumers can purchase two products together and they are not satisfied with the single product B2 anymore. When C is big enough, firm B is kicked out of the market and firm A gains a monopoly profit. However, for firm A, if it gives up bundling, firm B will gain profits by competing with firm A. Therefore, bundling ensures a monopoly position.We find that firm A rarely discloses quality, and the benefit brought about by disclosing real quality, even at high levels, has a minimal effect on the incentive to engage in bundling. For instance, if q2A R > 0.88, firm A discloses only when it bundles. Under such circumstances, if we set q2A R = 1, firm A discloses when it bundles and consumers gain a benefit of 1. Comparatively, if firm A does not bundle, it never discloses. Thus, consumers can gain a benefit of q2A *I/2 = 0.5. We can easily see that consumers gain a bigger benefit from quality disclosure under bundling, and hence, quality disclosure will attract more consumers under bundling. However, the advantage of the high quality of A2 has no effect on the decision concerning bundling, because the benefit from less-fierce competition under independent pricing is too great.

3. Conclusions

This study sought to understand the incentives of bundling by considering the effects of quality disclosure for a multiproduct firm. The firm monopolizes one market with a high quality product but competes with another firm in another market with a new product whose quality is unknown to consumers. The incentive to disclose quality for this firm under bundling is always stronger than it is under independent pricing. Importantly, bundling is never preferred when the level of consumers’ reservation value is relatively small, regardless of the cost to disclose and the real quality of the new, unknown product and competitor’s product. However, as consumers’ reservation value increases, the market can be captured if the multiproduct firm bundles and this bundling ensures its monopoly position and profits.

References

| [1] | Whinston, M. (1990). "Tying, Foreclosure, and Exclusion," American Economic Review, 80(4), pp. 837-860. |

| [2] | Matutes, C., and Regibeau, P. (1988). "Mix and Match: Product Compatibility without Network Externalities," Rand Journal of Economics, Vol. 19, pp. 221-234. |

| [3] | Gans, J. and King, S. (2005). "Paying for Loyalty: Product Bundling in Oligopoly," Journal of Industrial Economics, LIV (1), pp. 43-62. |

| [4] | Matutes, C., and Regibeau, P. (1992). "Compatibility and Bundling of Complementary Goods in a Duopoly," Journal of Industrial Economics, 40(1), pp. 37-54. |

| [5] | Thanassoulis, J. (2007). "Competitive Mixed Bundling and Consumer Surplus," Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16, pp. 437-467. |

| [6] | Armstrong, M., Vickers, J. (2006). "Competitive Nonlinear Pricing and Bundling," University College London, November. |

| [7] | Levin, D., Peck, J., and Ye, L. (2009). "Quality Disclosure and Competition," Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(1), pp.176-196. |

| [8] | Choi, J. P. (2003). "Bundling New Products with Old to Signal Quality, with Application to the Sequencing of New Products," International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21, pp. 1179-1200. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML