-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Game Theory

p-ISSN: 2325-0046 e-ISSN: 2325-0054

2012; 1(5): 38-42

doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20120105.03

Non Negative Benefits of the Commons in Infinitely Repeated Game

Prakash Chandra1, K. C. Sharma2

1Deptt. of Applied Science & Humanities, Dronacharya College of Engineering, Gurgaon, India

2Deptt. of Mathematics and Computer Science, MSJ Govt. College, Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India

Correspondence to: Prakash Chandra, Deptt. of Applied Science & Humanities, Dronacharya College of Engineering, Gurgaon, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In this paper, two groups use the commons as a resource with its near-sightedness and far-sightedness. We study the game with majority of the group and unanimity of the group in its decision making. And we look into the game with the individuals’ utility in making use of the commons with near-sightedness and farsightedness in infinitely repeated game. SPE exists for nearsightedness which tends to destroy the commons in near large period of the game but farsightedness makes safe and useful for infinite period of the survivility of the humanity.

Keywords: Tragedy of the Commons, Repeated Game, Utility, SPE

Cite this paper: Prakash Chandra, K. C. Sharma, "Non Negative Benefits of the Commons in Infinitely Repeated Game", Journal of Game Theory, Vol. 1 No. 5, 2012, pp. 38-42. doi: 10.5923/j.jgt.20120105.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Use of Commons

- Well know study by Garrett Hardin, “the tragedy of the commons”[3] describes the degradation of scarce resources that are open to all appropriators in society. Since all the appropriators have equal right to access to the commons and enjoy the value of the average product from the commons. As long as this average value is higher than the marginal value. Then new appropriators of the society are inclined towards at the difference come into the commons with the result that resources are drop. Hardin given a better picture of the tragedy of the commons; a pasture opens to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching, and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the natural logic of the commons mercilessly generates tragedy. To picture the situation, consider a lake with fish and one or more fishing boats. We distinguish between a non-strategic and strategic setting. In the non-strategic case, there is one boat on the lake deciding how many fish to catch, and how many to leave in order to ensure future population of the fish. The situation where there is only one fisherman on the boat represents an individual decision-making environment. Group of the three fishermen on the boat represents the group decision making. In the strategic setting various boats affect each other’s earnings via the price of fish on the market (determined by the number of fish caught) and by the consequences of their current catch for future periods. Once again, each boat may have one fisherman or the group of three.

1.2. Organization of the Problem

- Vision of two groups which have nearsightedness and farsightedness in making use of commons, where farsightedness in between two groups is only essential factor for long or infinite period survivility of the mankind with social welfarism which we look into two groups of the society (two states, two creeds, two castes, two organisations, treaty in between countries, trade in between two countries). Our all dimensions research look better ways of long survivility of humanity in the society but it is far beyond till lack of farsightedness. We have organized this paper in four sections considering the groups size remain constant in infinite periods or long finite periods; first section of the paper is introduction which describes many original works on the commons and global commons for the better use in near future and sustainability of the humans. Section two describes about the optimal use and over exploitation of the common. In section three is the study of the making use of the commons in respect of utility maximization not only payoff with a belief in respect of nearsightedness and farsightedness. In section four is the study of individuals’ use of common when the actions are non-observable. Section five is the conclusion of the making use of common with non-negative benefits in infinite play.

2. Payoffs vs Utility

2.1. Degree of over Exploitation

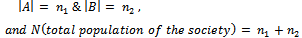

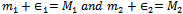

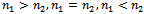

- Let the numbers of the groups are two which are respectively A and B. Cardinality of the groups A and B is n1 and n2 respectively or mathematically–we can write

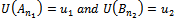

Utility of the groups A and B are–

Utility of the groups A and B are– . The society can sustain on the commons, making it in use properly. Let normalize the total population of the society

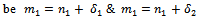

. The society can sustain on the commons, making it in use properly. Let normalize the total population of the society  . If we allowed the optimal exploitation (when the population of the groups is increasing by

. If we allowed the optimal exploitation (when the population of the groups is increasing by  ), then the size of population be

), then the size of population be  , and

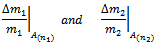

, and  are opportunity cost for group A and B. when we consider over exploitation on the given opportunity cost, then we can calculate the degree of over exploitation

are opportunity cost for group A and B. when we consider over exploitation on the given opportunity cost, then we can calculate the degree of over exploitation  where

where  are independent. The degree of over exploitation

are independent. The degree of over exploitation

2.2. Utility from Non-negative Payoff

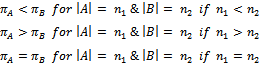

- Payoff of the group A and B which differentiate due to their size difference

In positive

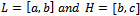

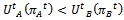

In positive  , there be three sections of the feasible payoff region, below we have shown graphical representation of the feasible payoff region. Utility function can be presented

, there be three sections of the feasible payoff region, below we have shown graphical representation of the feasible payoff region. Utility function can be presented ,

,

which is directly dependent on the payoff from the use of commons in each period. At ground reality, we human have finite year in making use of the commons but we are considering this use for infinite period, having in mind that player will change but intuition of non-negative use of commons remain as it for infinite period (having the aspect of future generations survivility). No group want to destroy the commons (surviving of the groups depend on the use of common) but want to use the commons in such a way – utility difference be close to zero for each group in each period (otherwise collusion between groups for the making use of the commons will take place which can destroy the commons for ever or there may be effect not to use of the commons for a long period of time).

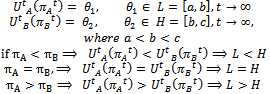

which is directly dependent on the payoff from the use of commons in each period. At ground reality, we human have finite year in making use of the commons but we are considering this use for infinite period, having in mind that player will change but intuition of non-negative use of commons remain as it for infinite period (having the aspect of future generations survivility). No group want to destroy the commons (surviving of the groups depend on the use of common) but want to use the commons in such a way – utility difference be close to zero for each group in each period (otherwise collusion between groups for the making use of the commons will take place which can destroy the commons for ever or there may be effect not to use of the commons for a long period of time).  But the sustainability of the commons works or come into reality if their utility to the groups near equal. Inequality of utility in making use of the commons may be the cause of the heavy destruction of the commons or stop the use commons for long period of time which may be reverse reason to finish the users due its missing. In some of the situations of the better or perfect making use of the commons demand the natural player which have no payoff in use of the commons but play the crucial role in the successful use of the commons in infinite period. Proposition 1: For static condition of the two groups, SPE exists if and only if the limit of the utility interval set of group A belong to the utility interval set of group B for each periods in infinitely repeated game. Here we are considering the static condition with the group’s population (there is increasing or decreasing element in the group membership). Neighborhood of

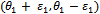

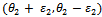

But the sustainability of the commons works or come into reality if their utility to the groups near equal. Inequality of utility in making use of the commons may be the cause of the heavy destruction of the commons or stop the use commons for long period of time which may be reverse reason to finish the users due its missing. In some of the situations of the better or perfect making use of the commons demand the natural player which have no payoff in use of the commons but play the crucial role in the successful use of the commons in infinite period. Proposition 1: For static condition of the two groups, SPE exists if and only if the limit of the utility interval set of group A belong to the utility interval set of group B for each periods in infinitely repeated game. Here we are considering the static condition with the group’s population (there is increasing or decreasing element in the group membership). Neighborhood of  is

is  where

where  and neighborhood of

and neighborhood of  is

is  where

where  .

.

is the limit points of L and H.

is the limit points of L and H.  ,

,  . There exist a SPE for the making use of commons, whereas we see the limit point of utility interval set of one group belong to the other which show close interrelationship between them to hold equilibrium. In other words we can say –it breaks the thought of dissatisfaction in making use of commons in each period, it works like a spirit of continuity between the groups

. There exist a SPE for the making use of commons, whereas we see the limit point of utility interval set of one group belong to the other which show close interrelationship between them to hold equilibrium. In other words we can say –it breaks the thought of dissatisfaction in making use of commons in each period, it works like a spirit of continuity between the groups | Figure 1.  |

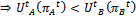

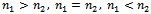

approaches to

approaches to  at each period in use of the commons when

at each period in use of the commons when  .As we have shown utility function of the groups at each period of time. If

.As we have shown utility function of the groups at each period of time. If  or

or  at real line and

at real line and  is the midpoint of utility of the groups then for the group A, neighborhood of the utility θ1, touches θ at least, hold the equilibrium in the making use of the commons in spite of their payoff differences due to the size of the groups which shows as per their need, they are making use of the commons but utility differences are negligible or in the neighborhood of each other. For the group A on the payoff at period t is

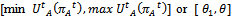

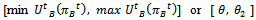

is the midpoint of utility of the groups then for the group A, neighborhood of the utility θ1, touches θ at least, hold the equilibrium in the making use of the commons in spite of their payoff differences due to the size of the groups which shows as per their need, they are making use of the commons but utility differences are negligible or in the neighborhood of each other. For the group A on the payoff at period t is  which is not always generating fix utility but interval of utility- minimum utility and maximum utility which is min

which is not always generating fix utility but interval of utility- minimum utility and maximum utility which is min  max

max  , we can present in interval as

, we can present in interval as  . And For the group B on the payoff at period t is

. And For the group B on the payoff at period t is  which is not always generating fix utility but interval of utility- minimum utility and maximum utility which is min

which is not always generating fix utility but interval of utility- minimum utility and maximum utility which is min  max

max  , we can present in interval as

, we can present in interval as  where

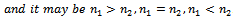

where  .Example:-Satellites Occupy in the Orbital Space (Global Commons)-Let the cardinality of the countries in group A and B are

.Example:-Satellites Occupy in the Orbital Space (Global Commons)-Let the cardinality of the countries in group A and B are  and

and  and total the capacity of the satellite to be placed in the orbit is N. If total possible launched satellite be

and total the capacity of the satellite to be placed in the orbit is N. If total possible launched satellite be  ,where maximum level from A-group and B-group is

,where maximum level from A-group and B-group is  and

and  respectively,

respectively,  . It is the game of complete information (each player know how much satellite can be launched now or empty space to the possible number of satellites), where each group decision to launch an extra satellite can destroy all the system in the orbit which be the cause of heavy loss to both the player groups. Therefore each group player cannot make any decision without permission from the other group player. It means that the decision of the launching satellite be unanimously taken with awareness towards each other. This cooperation between the groups holds due to their farsightedness and welfarism towards humanityProposition 3: If group A and group B have farsightedness and nearsightedness respectively then limit point of utility set of A does not belong to utility set of B when

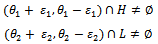

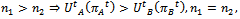

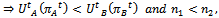

. It is the game of complete information (each player know how much satellite can be launched now or empty space to the possible number of satellites), where each group decision to launch an extra satellite can destroy all the system in the orbit which be the cause of heavy loss to both the player groups. Therefore each group player cannot make any decision without permission from the other group player. It means that the decision of the launching satellite be unanimously taken with awareness towards each other. This cooperation between the groups holds due to their farsightedness and welfarism towards humanityProposition 3: If group A and group B have farsightedness and nearsightedness respectively then limit point of utility set of A does not belong to utility set of B when  .For all this

.For all this

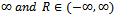

, utility difference is high due to their vision in making use of the commons which is for group A, is farsightedness and for group B, is nearsightedness. Where nearsightedness imposes to maximize the payoff verses utility high as much as possible in each current period of use the commons without having the thought to save for the future which directly imposes the destruction of the commons. Group B play rationally in to each period. Whereas farsighted vision of the group player A use the commons as per the requirement, having the aspect with the commons to save it and to make use in each period of the coming future without harming. Intersection of the neighborhood of the utility of the group A and utility interval of the group B is null. SPE does not exist which means that the use of the commons soon might be destroyed due to one of the group’s nearsightedness. Therefore there is need to play central role by third player (nature) who does not have any incentive from the commons which look into the survivility of both group in future with the commons. Or this player make the decision for each group, how much each group can use the commons with making possibility to survive today with future aspect ( fix amount use in each period) and coming future with survivility of the next generations. Third player (punishment cell) punish also on the each single extra unit of the commons in each period of the game. Proposition 4: If both groups A and B have nearsightedness then SPE exist for finite periods. The use of commons for future (after finite period of the play) be no more. Nearsightedness imposes the player to maximize the benefits in each periods of the play without having the future aspect of making possible use of the commons. Each group have the limit point of its utility in the others utility interval upto finite period of the play. There exist SPE of the game in that period but having SPE of the game in that period is not guarantee to have SPE in the next period with same efficiency for the player groups .It implies the destruction of commons (Degree of over exploitation is high or close to one or more than one as finite time period increases) and they will not be able to survive in near future because of not having the proper quantity to use from the commons.Proposition 5: If both groups A and B have farsightedness then SPE exist for infinite periods when

, utility difference is high due to their vision in making use of the commons which is for group A, is farsightedness and for group B, is nearsightedness. Where nearsightedness imposes to maximize the payoff verses utility high as much as possible in each current period of use the commons without having the thought to save for the future which directly imposes the destruction of the commons. Group B play rationally in to each period. Whereas farsighted vision of the group player A use the commons as per the requirement, having the aspect with the commons to save it and to make use in each period of the coming future without harming. Intersection of the neighborhood of the utility of the group A and utility interval of the group B is null. SPE does not exist which means that the use of the commons soon might be destroyed due to one of the group’s nearsightedness. Therefore there is need to play central role by third player (nature) who does not have any incentive from the commons which look into the survivility of both group in future with the commons. Or this player make the decision for each group, how much each group can use the commons with making possibility to survive today with future aspect ( fix amount use in each period) and coming future with survivility of the next generations. Third player (punishment cell) punish also on the each single extra unit of the commons in each period of the game. Proposition 4: If both groups A and B have nearsightedness then SPE exist for finite periods. The use of commons for future (after finite period of the play) be no more. Nearsightedness imposes the player to maximize the benefits in each periods of the play without having the future aspect of making possible use of the commons. Each group have the limit point of its utility in the others utility interval upto finite period of the play. There exist SPE of the game in that period but having SPE of the game in that period is not guarantee to have SPE in the next period with same efficiency for the player groups .It implies the destruction of commons (Degree of over exploitation is high or close to one or more than one as finite time period increases) and they will not be able to survive in near future because of not having the proper quantity to use from the commons.Proposition 5: If both groups A and B have farsightedness then SPE exist for infinite periods when  .Inclination towards farsightedness of the both groups is a boon for the society where it inclined the welfarism of the society and not interested to maximize their personal payoffs. They have belief to long survivility of the humanity for making use of the commons. Intersection of the neighborhood of the utility of the group A and utility interval of the group B is not null for each condition of the group

.Inclination towards farsightedness of the both groups is a boon for the society where it inclined the welfarism of the society and not interested to maximize their personal payoffs. They have belief to long survivility of the humanity for making use of the commons. Intersection of the neighborhood of the utility of the group A and utility interval of the group B is not null for each condition of the group  and for each periods of the play. There exists a SPE in such each period of the infinitely repeated game.

and for each periods of the play. There exists a SPE in such each period of the infinitely repeated game.3. Individual Commons Use

3.1. Individual Payoff Function

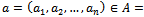

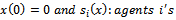

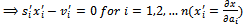

- If

individual agents have non-observable action

individual agents have non-observable action  and private (non-monetary) cost

and private (non-monetary) cost  , where

, where  : strictly convex, differentiable and increasing and

: strictly convex, differentiable and increasing and  . Let

. Let

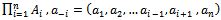

,

,  . A joint monetary outcome of the agents,

. A joint monetary outcome of the agents,  , where x: strictly increasing, concave and differential and

, where x: strictly increasing, concave and differential and  share of the outcome

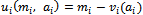

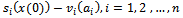

share of the outcome  . Let the preference function of agent I is

. Let the preference function of agent I is  , agents’ initial endowments of money are finite and normalized to be zero. Non-cooperative game with payoffs

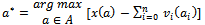

, agents’ initial endowments of money are finite and normalized to be zero. Non-cooperative game with payoffs  has a NE

has a NE  , which satisfies the condition for Pareto optimality.

, which satisfies the condition for Pareto optimality.

3.2. Nearsightedness Vs Farsightedness

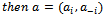

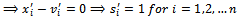

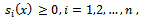

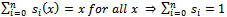

- If sharing rules are differentiate then

is NE

is NE  . Pareto optimality

. Pareto optimality  from sharing rules

from sharing rules  such that we have budget-balancing

such that we have budget-balancing  . To reach efficient NE, sharing rule differentiable does not allow. Individual agent i can impose nearsightedness in use of the commons which is rational decision for an individual agent of the society. They are noncooperative to maximize their utility. If they look into the sustainability, it apply-farsightedness and it impose them to come to make all decisions with cooperation of each other.

. To reach efficient NE, sharing rule differentiable does not allow. Individual agent i can impose nearsightedness in use of the commons which is rational decision for an individual agent of the society. They are noncooperative to maximize their utility. If they look into the sustainability, it apply-farsightedness and it impose them to come to make all decisions with cooperation of each other.4. Conclusions

- There are two believes (nearsightedness and farsightedness) of the groups whose survivility depends on the making use of the commons in each period of the game. Here, our assumption is constant size of the groups with each periods of infinitely play of the game. We study the existence of SPE of the game in each period which not makes sure us the survivility of the group in near future. But for the survivility of the group, the belief in respect of farsightedness work here as invisible hand which led the best decision for the entire society, depend on the well used common(optimal level utilization of the commons in each period of the game). Example of the orbit use for the development of technology is essential, where decision based on complete information and farsightedness of the groups in each period. Individual commons use also maximizes the utility and make possible the survivility with the inclination of farsightedness for infinite periods of game. If degree of over exploitation is close to one then there is fast rate of destruction of the commons. If it is more than one then there is quick destruction of the common take place. Optimal exploitation is also over exploitation but its degree is zero which makes the non-negative use of commons for both groups for infinite periods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to thank the editors Cathy Jones & Mark Green and the anonymous referees for their comments that helped me considerably improve the form and the content of the paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML