-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Civil Engineering Research

p-ISSN: 2163-2316 e-ISSN: 2163-2340

2021; 11(1): 10-18

doi:10.5923/j.jce.20211101.02

Received: Mar. 16, 2021; Accepted: Apr. 9, 2021; Published: Apr. 15, 2021

Prefabrication as a Solution for Tackling the Building Crisis in the UK

Abdussalam Shibani, Araz Agha, Thuraiya Alharasi, Dyaa Hassan

School of Energy, Construction and Environment, Coventry University, Coventry, CV1 5FB, United Kingdom

Correspondence to: Araz Agha, School of Energy, Construction and Environment, Coventry University, Coventry, CV1 5FB, United Kingdom.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The UK as a welfare state spends about 30% of the gross domestic product on social expenditures. The acute and biting shortage of housing, particularly social and affordable housing is responsible for the spiralling house prices and rents leading to an affordability crisis. Evidence-based research shows that the UK needs to build over 300,000 houses a year to meet the rising demand, particularly from young adults and families with low-to-middle incomes. As a result, there has been a worrying increase in overcrowding, homelessness, evictions and rent arrears. This research study aimed to investigate prefabrication, also known as modular construction as a solution to tackling the housing crisis in the UK. A mixed method approach was used to collect raw data. As such, five major construction firms were selected as the case study organisations for the research study. The respondents had a senior position in the organisations. The data collection methods that were adopted are qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (questionnaires). The data were analysed using thematic analysis in which emergent themes were identified throughout the interviews and the questionnaires. Findings suggested that the housing crisis is not about houses; instead, it is about individuals. Perceptions about prefabricated houses among the low, middle and high-income earners are largely negative whose implication is that individuals would rather wait to build traditional homes in the future than opt for a prefabricated home. Although traditional home ownership is slipping out of reach for the majority, the demand for prefabricated homes is still low. In urban areas, modular construction is practised on a small scale with the main market limitations being the small size of the domestic market and the existing building regulations which prohibit the use of inflammable materials in urban areas. Moreover, it was found that prefabricated homes may provide short-term and long-term solutions to the housing crisis since they address and resolve some of the most critical issues associated with traditional housing but not limited to high costs, longer construction periods and uncertain budgets.

Keywords: Prefabrication, Housing Crisis, UK

Cite this paper: Abdussalam Shibani, Araz Agha, Thuraiya Alharasi, Dyaa Hassan, Prefabrication as a Solution for Tackling the Building Crisis in the UK, Journal of Civil Engineering Research, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2021, pp. 10-18. doi: 10.5923/j.jce.20211101.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- England is the most affected by the shortage of housing among the countries that constitute the UK. According to Bowie (2015) [1], there is a severe crisis of housing supply, particularly in the South-East and London. Wilde (2016) [2] reports that the housing crisis in the UK is not limited to a shortage in the numerical supply of homes only but also a scarcity of affordable homes. As such, the overall output of new homes has continually been significantly below the annual estimates of housing requirements. A report by the House of Commons in 2016 puts the annual requirements for new housing at 240,000 to 280,000 houses. However, the housing output in England for the last five years has averaged 100,000 to 125,000 houses a year [2]. Thus, the annual housing output in the UK is barely meeting half of the demand for housing. In London, the housing requirement has been assessed at about 60,000 homes a year but the output has ranged from 15,000 to 18,000 houses annually. Besides, overcrowding and under-occupation of rented homes have grown in parallel [3]. Therefore, the current housing crisis in the UK encompasses inappropriate supply, unaffordability, under supply and ineffective use of the existing housing stock due to problems of access, quantity, quality, and distribution. The UK should be building about 250,000 houses a year in an attempt to keep up and satisfy the requirement of the rising demand for homes. Furthermore, the country should be constructing about 300,000 homes a year to reduce the deficit in supply, which is responsible for the upsurge in the prices of homes. A recent survey by Buildoffsite found that the proportion of the UK’s offsite market compared to the net worth of the entire UK construction sector is a paltry 2.1%. Unlike other countries, the word “prefab” in the UK conjures images of ready-made, cheap and squat homes used in the post-Second World War period to address the housing shortage that was prevalent [2]. However, the post-World War II UK bears little resemblance to the modern country. As such, the construction planning rules are tighter, the land is scarcer and the house building industry is overly dominated by large commercial firms that practice traditional-style construction for the sake of profits. Although offsite construction is not cheaper compared to “traditional” construction methods, it makes the costs of construction more predictable. According to Wilde (2016) [2], the adoption of prefabricated homes is complicated by the “bad” association related to the immediate post-war period. Additionally, debt providers and mortgage lenders are often reluctant to lend significant sums for building modular homes since it is difficult to make profits or repossess them.

2. Literature Review

- Sharam and Hulse (2014) [4] define industrialised building systems defines them as those incorporating a total integration of all subsystems and components into an overall process, one fully utilizing industrialized production, transportation and, assembly techniques. Stephens (2011) [5] goes a step further and classifies building systems into four comprehensive categories. These are prefabrication, modular coordination, rationalized and equipment-oriented systems. He points out however that the four forms are not collectively exhaustive nor mutually exclusive and observes that "new forms may and will develop while the four forms can and do co-exist within the same organization.” Concerning prefabricated building systems, Bowie (2015) [1] criticises traditional definitions that tend to create a wide divide between conventional and prefabricated houses. Instead, he argues it is impossible to define the term prefabrication in terms of compatible qualities. As such, there seems to be no exact boundary between prefabrication and other forms or methods of construction and on this account; it is prudent to keep an open mind [6]. The difficulty in its definition and in trying to give it boundaries can be easily seen from the various attempts by different authors to define it. For the purpose of this study, prefabrication will be taken to mean a form of industrialisation which consists of producing parts which when assembled will give a finished product [7]. When utilizing this form it does not matter whether it is factory or site-prefabrication. "Of more relevance" observes Kolo et al., (2014) [8] is the fact that “when utilizing this form of construction, individuals have to design the finished product first, and then break it down into meaningful parts and finally assemble them in correct sequence and order.

2.1. Current Housing Crisis in the UK and Selected Countries and the Factors Contributing to the Shortage

- Kolo et al. (2014) [8] observed that, housing is a necessity of life and a prerequisite for the decency, welfare, health, safety, and survival of humankind. Aziz and Hafez (2013) [9] opine that housing is a top indicator of individuals’ standards of living and their place in the society. In most countries, population explosion, which exceeds the rate of economic growth, is the leading cause of housing crises. In the UK context, the situation is unique in that there are several other factors that influence the adoption and uptake of prefabricated homes. Netto and Abazie (2012) [10] found that the post-war perceptions of “prefabs” have a strong influence on house buyers and the construction industry players. As a result, house buyers in the UK tend to resist any innovations in constructions that compromise the outlook of a “traditional” house despite cost advantages [11]. Besides, the human perception barrier based on the historical failure of offsite practices exists among UK designers and architects [12] The negative perceptions among house buyers and builders coupled with technical difficulties, such as interfacing problems, specifics and logistics, the fragmented structure of the supply chain and the associated high costs impede the acceptance of prefabrication among buyers and builders [13]. It is important to note that the high costs are associated with the lack of economies of scale due to low adoption of offsite technologies. Sharam and Hulse (2014) [4] interviewed 27 key players in both housing development and manufacturing. It was found that the adoption and uptake of offsite manufacturing technology are partly influenced by the developers’ perceptions concerning its advantages and demerits, which are influenced by regulatory factors and wider market perceptions. However, according to Michail (2011) [14] who found that market drivers and various policies regulating the construction industry were contributing to an upsurge in the offsite construction techniques. The findings are in agreement with a recent cross-industry offsite market survey in the UK that established that the use of prefabricated homes brings benefits based on increased quality and shorter onsite duration [2]. However, the perceived or real cost of prefabricated houses compared to “traditional” methods and the long lead-in times were found to be major barriers.Several research studies have established that the population explosion and a limited diversity in the construction processes have led to the housing crisis in Nigeria. Unlike the UK, there is a significant skills shortage particularly in innovative construction [15]. Prefabricated houses are considered more expensive compared to “traditional” techniques, which are more established. Similar to the UK, research studies have demonstrated that prefabricated housing contributes to savings in the areas of overall life cycle costs, cost certainty and reduced risks. Other associated benefits are drawn from the better quality of prefabricated buildings, which include reduced maintenance costs and fewer site overheads and preliminaries [12]. Empirical research has found that the time spent in constructing a house can be reduced by 30 ‒ 50% thereby leading to cost advantages for the benefactors.Concerning the benefits of prefabrication in addressing the current housing crisis, it is a bittersweet situation in the UK. As stated earlier, the principal advantage of using prefabrication is that time is reduced. As a result, there is a reduced impact on the site and the local environment [15]. Ordinarily, site work is usually vulnerable to disruption by the vagaries of weather thereby leading to longer delays and increased costs. However, sites are less vulnerable through prefabrication leading to reduced risks of delay. According to Lowe et al. (2006) [16], prefabrication offers opportunities for dealing with problems arising from skilled labour shortages onsite and declining workmanship standards. Stoy et al. (2008) [3] note that in factory environments, the quality of finished products is much easier to ascertain compared to “traditional” construction processes. According to Stephens (2011) [5], careful quality control of manufacturing processes facilitates wastage control and minimisation through recycling and appropriate design processes. Besides, the use of prefabricated components minimises site spoilage associated with “traditional” practices. As such, “traditional” practices contribute to significant site spoilage particularly through poor site handling and over-ordering.Several researchers [1] [2] and [17] have investigated the modern barriers to the uptake of prefabricated houses. The researchers have characterised the barriers as generic factors that challenge sustainability within the construction industry in the UK. As mentioned earlier, the general image of prefabricated houses is coloured by the experience of past application. Also, the benefactors’ perceived performance of prefabricated house counts a major consideration in the adoption of offsite building techniques. According to Michail et al. (2011) [14], most of the prefabricated homes built between after 1945 have been perceived as having shorter lifespans compared to their equivalent traditional buildings [13]. The perception that prefabricated homes are temporary solutions to housing shortage is a barrier to uptake and adoption as a mainstream procurement option. Felix et al. (2013) [15] identifies the current construction industry culture as a major impediment in the uptake of prefabricated houses. For example, there is a shortage of plants that handle larger prefabricated components.

2.2. Production Continuity and Its Relation to Prefabrication

- It is well known that the primary objective of industrialisation is one of reducing unit cost through continuous production, of standardized elements [13]. To achieve this, the production line has to be sustained for long periods of time. Only then will management and labour reach high levels of productivity and the risk of undertaking the investment start to pay off [17]. This in essence suggests the need for big and steady markets to support the production line. Unlike the case of a conventional builder who builds hundreds of units per year profitably, the prefabricator must produce thousands of units annually to obtain real cost savings (Akadiri 2011). This is a major issue with construction companies in the UK. While the technology is easily available, the low demand for prefabricated units renders it unsustainable to maintain prefab lines with low demand.

2.3. Construction Materials

- Almost all the building materials can be used in prefabricated form. It presupposes the existence of the necessary production technology and economic status supportive to the development and maintenance of the technology [9]. Presently however, wood, concrete and steel are the predominant materials used in prefabrication of houses. Throughout the development of the industry, wood has been the oldest and widely used material in prefabrication mainly because of its ease in handling, availability and in most parts of the world it is one of the major traditional building materials [5]. With time however, the use is becoming less frequent because of rising costs of timber due to shortages and wood frame construction can only be used for low-rise structures thus limiting its use in storeyed buildings [12]. Concrete and steel are equivalent in use, and their functions are often interrelated. In most parts of the world, however, steel is an imported item, and its use places a severe pressure of balance of payments. Its use in construction is, therefore, highly curtailed (Wilde 2016). Concrete as a building material has several advantages It provides excellent sound insulation, has good thermal qualities, good fire resistance qualities, can be moulded to almost any shape and provides a monolithic structure when properly reinforced [26]. Consequently, many systems especially in Western Europe are concrete because it is readily available in most areas, versatile in its use and relatively cheaper than most other building materials on a cost/unit of volume basis [25]. The wide availability and affordability of modular construction materials in the UK renders prefabricated homes as permanent solutions to the crisis. As far as their use for housing and commercial buildings is concerned, transportation costs offset substantially any advantage of prefabrication (Tam 2011). Since the elements are simple, the ratio of transportation cost to production costs increases rapidly to uneconomical levels [1]. The economics however change when they are considered for industrial and educational buildings which usually, require large open spans. In this case post and beam systems (especially concrete and steel) can be used to their fullest potential.This study aims to examine the factors that lead to low adoption of prefabricated homes and those that may promote their adoption. The objectives are: Explore and assess the reasons behind the current housing crisis in the UK and the factors which have contributed to the housing shortage. Also, to investigate prefabricated houses as permanent solutions for addressing the housing deficit in the UK. Finally, to identify barriers and implications behind using prefabrication method for the UK housing sector.

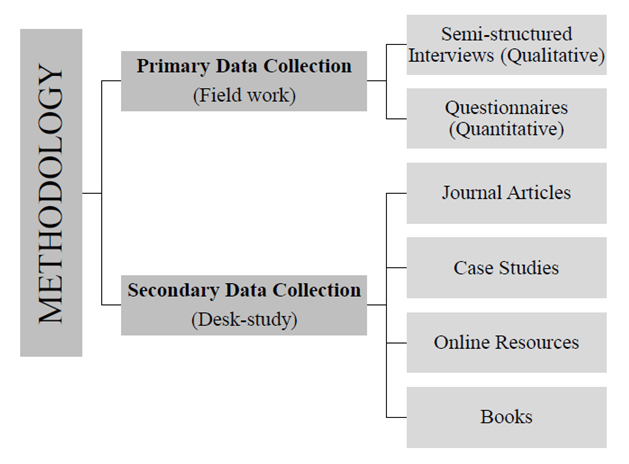

3. Methodology

- According to Given (2008) [22], the methodology of any research study is the spine since it provides the rationale for the processes and actions performed to investigate a research problem. In accordance to this, the highlighted purpose of this research methodology is to provide reasoning for selecting the methods used in this study, in order to achieve its objectives. Thus, this methodology discusses the specific procedures used in the identification, processing or interpreting and analysis of the raw data. The research used various methods to collect and collate data. Five major construction firms in the UK were selected as the case study organisations for the research study. Moreover, the case study organisations are selected cautiously in order to satisfy the objectives, furthermore, to support the feasibility of this study by representing and reflecting the current situations of the crisis. A case study approach was the most appropriate in this context since it provided a real-life and practical context to research [18-19]. As such, there is a necessity to understand data and phenomena in their natural environment. Moreover, a descriptive case study methodology is adopted since it facilitated the gathering data without changing the environment in attempts to demonstrate relationships among objects in their natural environments. The study employed a non-probabilistic method to recruit participants for the study. As such, the purposive sampling approach was used where experts in the UK’s construction market were selected to participate in the study. Respondents from various companies in the construction industry volunteered to participate. The necessity of the approach according to Bulsara (2014) [19] is emphasised by the need to use cases that have the required information that assists in the fulfilment of the research aims and objectives. Thus, five participants from the largest construction companies in the UK participated and provided objective information that reflects the status of the industry.

3.1. Qualitative Methodology

- The qualitative approach involved the use of semi-structured interviews. The interviews provided a significant core to addressing complex and in-depth issues associated with prefabrication that may not be covered using statistical methods alone.

3.2. Quantitative Methodology

- The quantitative methods produce data that paints the accurate picture of a study phenomenon. The quantitative method entailed administration of questionnaires to the representatives to assessing their beliefs and perceptions towards prefabrication as a solution to the current housing crisis [20].

3.3. Ethical Aspects

- Participants were informed of their right to voluntary participation [19]. As such, they were made aware that they possess the right to withdraw from the study at any moment without incurring any damage or harm. Besides, participants were assured that their records of participation were destroyed upon their withdrawal. Second, participants were presented with an information sheet and consent form detailing the specifics of the proposed study [22]. They were given ample time to study and decide whether to participate in the research study or not. A signature was required on the consent form to authorise participation. Third, participants were assured of their confidentiality while participating in the study to protect their dignity. In this regard, their names were replaced with monikers and were not published [20].

| Figure 1. Classifications of Methodology |

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Data Analysis

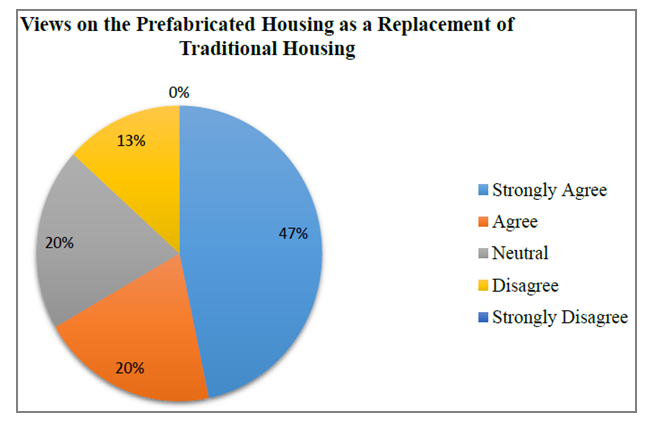

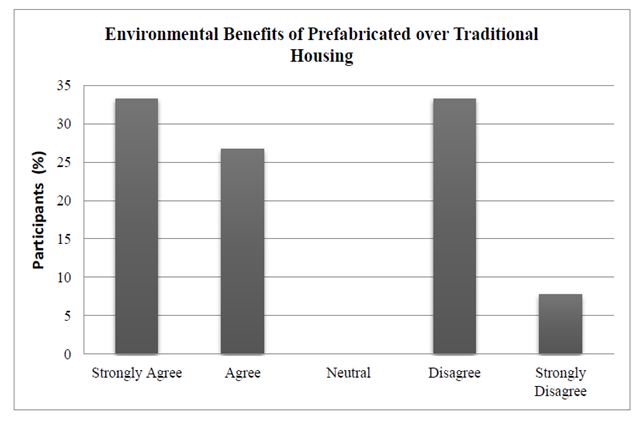

- Data was collected through interviews. As such, employees in the top cadre in each organisation were interviewed. While questionnaires were predefined, interviews were lax and they allowed the participants to follow their trajectories instead of operating within the confines of the interview questions [21]. The interviews were based on the research question and the research objectives. Face-to-face interviews were preferred to video calls. Besides recording data, note taking was also used to record data. Concerning analysis of the raw data, a thematic analysis approach was used for qualitative data. In the thematic analysis, emergent and latent themes from the interviews are identified and developed [20]. The themes were correlated to the research question and the research objectives of the study. The process is interactive and entails distilling anonymous judgments from experts by identifying salient and latent themes. On the other hand, qualitative data from the questionnaire were coded and assigned numerals for further analysis.Prefabricated housing techniques and methods are an appropriate and suitable replacement for conventional building. In regard to, the quantitative research, it was generally established that prefabricated housing methods are an appropriate replacement of or a conventional building. 67.7% (40.7% strongly agreed and 20.0% just agreed) of the respondents agreed that that prefabricated housing is better for replacing the conventional building style. Most of the reasons for agreeing were that: the prefabricated houses were cheap and easy to erect since little materials are required compared to the traditional building; they were time saving since the structures are simple and architect’s designs; and the design flexibility was high. However, 13.3% of the respondent disagreed with the idea that prefabricated housing is a solution and a better replacement for traditional housing. The main reason mentioned was that the prefabricated house lowers the reputation. Moreover, 20.0% remained neutral to the whole idea of prefabricated housing system. Figure 2. illustrates these findings.

| Figure 2. Views on Prefabricated Housing as a Replacement of Traditional Housing |

| Figure 3. Views on Prefabricated Housing as a Replacement of Traditional Housing |

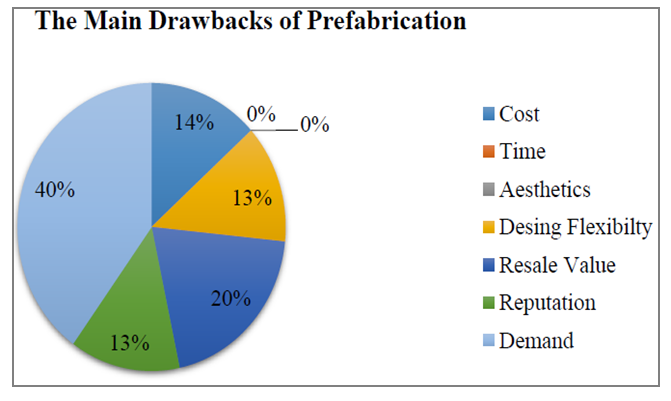

| Figure 4. The Main Drawbacks of Prefabrication |

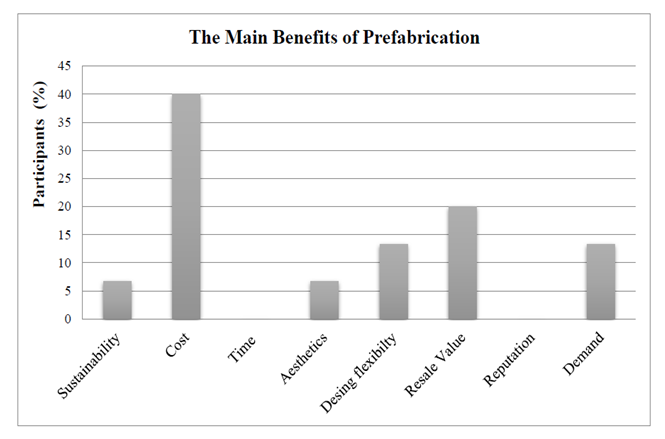

| Figure 5. The Main Benefits of Prefabrication |

4.2. Discussion

- Pre-fabrication housing practices remain vital in understanding the UK's needs in developing reasonable housing emergency, as reported by those interviewed (67.7%, where 40.7% strongly agreed and 20% just agreed). It is evident that Pre-fabric-fabrication housing practices of development techniques are necessary arrangement and money related levers to handling the cost of proper housing. It is vivid that a ton of things needs to be set up before a comprehensive and sound take off pre-fabrication. As indicated, 13.3% of the responded indicates that cost is a factor in prefabrication. Therefore, land cost is vital and unquestionably where that is high, then it is troublesome to implement the pre-fabrication housing practices plans or programs. In any case, where construction charges are brought down it turns out to be more significant, yet it is essential to locate the correct scale, and there is the need to have proper development frameworks and coordination [23]. Four market-situated "levers" are point by point that can direct advancement Pre-fabrication housing practices and lessen the cost of housing making it reasonable for house acquisition. These incorporate measures to increase activities and support productivity and reduce financing costs for purchasers and designers. In the field of architecture, architects are faced with myriad challenges. This is because most of the traditional structures are energy efficient and green thus they can be improved by climate, locally available resources, and geography. However, in the global context methods and technology-based tradition architecture is limited surprisingly beyond performance. Limitations hindering tradition architecture research originate from myriad factors, one of the significant factors hinged on the conventional concepts of “traditional” and “current” in the field of architecture [27]. Different studies on traditional architecture have led to ambiguities factors to arise from the different definitions of particular terms and concepts. In architecture, the terms “traditional” and “modern” are frequently regarded to be very fundamental in opposition each other. One of the factors that prove traditional architecture is a traditional form of architecture is its difference from the modern architecture. In a dualist view, traditional architecture is considered to be technologically crude or inept [27]. This perception does not only establish a tradition architecture to be different it also shows that it’s closely static and immutable, “certainly improvable, because it serves its objective to perfection.” The implication for the construction industry is to come up with ways of improving stability, outlook, tolerance and other salient factors that influence consumers’ choices. As such, devising strategies for sustainability enhancement in housing development is difficult, not because the nature of affordable housing construction is complex, but because the concept is ambiguous, multi-dimensional and generally not easy to understand outside the single issue of mitigating the housing shortage.Moreover, Beracha and Johnson (2012) [24] suggest that the decision-makers and building developers are adequately informed on sustainable development issues, local characteristics and community needs is the best identification for the effective urban sustainable development strategies. This approach requires the application of a suitable operational framework and an evaluation method that is able to guide developers through the decision-making. However, at the moment, such a structure for organising the information required in decision-making is not yet available or agreed upon among the stakeholders involved in the provision of affordable housing. However, a myriad number of empirically based architectural works from Asian tradition buildings suggests that materiality, sharp details, adaptive and smart-space techniques and solutions are well utilized by the traditional anonymous builders in a traditional situation as by well-known modern architects [27]. Tradition architectural studies results are shunned by the incomplete development of research which openly addresses the usage and application of traditional skills and knowledge in modern architectural designs. The interviews contend that crossing over this housing gaps represents a massive open door for the development of business and accommodating of homeless individuals in the UK.However, the choice and selection of appropriate production technology is of paramount importance especially in the construction industry which is a major economic activity in the UK. The choice of the suitable production method is an important task, therefore and should be based on the careful, systematic and detailed analysis [25]. In the past, however, such selection has been undertaken in a blatant manner owing to the lack of formal procedure, the choice has been more a matter of persuasion or chance than of objective judgement. The choice in most cases than not has been based on profit and personal motives rather than on systematic economic analysis. The capacity to pay for expanding the Pre-fabrication housing practices as-as solution to housing issue in the UK is estimated to close the housing gap between what individuals can bear the cost of and the cost of housing right with the increment as worldwide populaces keep on urbanizing. The interview report denotes that the utilization of off-site produced segments to support speed and productivity of development is essential to boosting effectiveness and, with other obtainment and process enhancements, venture conveyance expenses can be decreased by around 30% and culmination calendars can be abbreviated by approximately 40%. Therefore, a lot of things should be set up before pre-fabrication takes off. The interview report reveals that the gap in the housing sector of the US could be split or filled by applying the four levers in an extensive program.Solving the issue of the supply of land in the correct area is the most intense lever to address the land crisis through prefabrication. In numerous urban areas, the developable land stays out of gear, motivating forces like the taxes and charges of the idle land. Indeed, even in New York some of the privately zoned lands are undeveloped. Governments can likewise open underused open land in focal areas, grow new land with travel and other foundation, and change the land utilization rules [24]. Land can be presented for improvement through motivating forces, for example, thickness rewards, which include raising the allowed floor space on a plot of land and, along these lines, the land esteem; consequently, the engineer is required to give land to moderate units.Reducing developmental costs: while fabricating and different businesses have brought profitability consistently up in a previous couple of decades, development efficiency has stayed level or declined in numerous nations. In multiple spots, private lodging is worked in a similar way it was 50 years prior. By utilizing esteemed building practices (institutionalizing plan components) and modern methodologies (pre-assembled parts produced off-site), and by embracing proficient acquisition strategies and different process changes, venture conveyance expenses can be lessened by around 30% and finish calendars can be abbreviated by approximately 40%. Improved tasks and upkeep, for instance through vitality proficiency retrofits or building support activities at scale, can cut progressing costs. Lowering financing costs for purchasers and engineers through better access to lodging money, including guaranteeing for low-wage borrowers and creating contract markets [24]. Innovations in and industrialization of the production process in the construction industry have been viewed as the most promising possibilities for reducing costs, increasing productivity and in certain case, improving the quality of prefabricated homes. However, the lack of embracement of building technologies among the UK citizenry is worrying. It is interesting to note that even in other advanced countries; the problems of industrializing the building sector have not been solved yet.On the industry level, there is the need to invest in prefabrication technologies to facilitate continuous production albeit the fact that other supply factors are necessary. These includes adequate and cheap land for factory location, steady supply of raw materials for volume production, dependable supply of labour, availability of machinery at reasonable prices, supply of money at reasonable interest rates, good and efficient organizational and management structures and other infrastructural institutions to support mass production [9]. In a developed county like the UK, mechanization of both muscle power and brainpower with machinery and automation respectively results in standardised products at reasonable prices or costs, which may appeal to the customers to consider prefabricated homes as alternatives. Industrialising the prefabrication industry requires the introduction of mechanical equipment’s in building and assembly operation in order to increase productivity, minimize heavy manual work and improve quality. Site operations including concreting and mixing of mortar, vibration and compaction, transportation, plastering could all be done by the use of machines which are faster, precise and efficient.On the other hand, standardization and mass production together with functional simplicity are necessary if savings in time and money are to be realised [2]. Besides, integration and good coordination of the various subsystems in the building process implies a smooth and continuous production avoiding all delays and time waste which is a characteristic of conventional building methods where the parties involved in the building process are separated with each trying to advance their own interests regardless of the goals and objectives of the overall project. The coordination of the building process in industrialised system tends to be more complex requiring well-trained and experienced managers to cope with the extra responsibilities. This issue implies a good liaison between the professionals and the contractors, planned supply of raw materials, timely delivery of finished goods and efficient stock control measures. In this way, it is easy for the firms to achieve an overall optimization goal.

5. Conclusions

- The study weighed up the powers for dormancy against the drive for change in techniques for building and construction developments. The investigation demonstrates that while the body of evidence for and against the advancement of the pre-fabricated housing seems to turn on money-related expenses and advantages, practically speaking, social, cultural and specialized contrasts – battles over the gathering and improvement of pre-fabricated housing development markets. The findings contend that the national housing development and administration need to be proactive if its point is to support the growth of pre-fabricated homes. Hypothetically, this research uncovers that the UK building industry is on track to convey the administration of the pre-fabricated housing objective. The challenge is to keep availing the supply in the most affected regions to address the house shortages.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank the School of Energy, Construction and Environment, Coventry University. As well as reviewers and editor for their valuable comments.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML