-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Civil Engineering Research

p-ISSN: 2163-2316 e-ISSN: 2163-2340

2020; 10(1): 1-9

doi:10.5923/j.jce.20201001.01

Assessing the Significant Factors Contributing to Extension of Time in Road Construction Contracts in Ghana

1Department of Building Technology, Tamale Technical University, Tamale, Ghana

2Department of Feeder Roads, Sunyani Metropolis, Ghana

Correspondence to: Dok Yen D. M., Department of Building Technology, Tamale Technical University, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study was to assess the significant factors contributing to the extension of time within the road construction sector in Ghana. A quantitative study was conducted within the road agencies in the Sunyani Metropolis namely; Ghana Highway Authority, Department of Urban Roads and the Department of Feeder Roads. A total number of sixty-two (62) questionnaires were administered to management professionals (quantity surveyors, contract managers and engineers) for this study. Relative Importance Index, the mean score and One-Sample test were used for analysing the data. Adverse weather conditions, changes to the original contract scope, and suspension of work revealed to be the most significant factors contributing to extension of time in road construction contracts in Ghana. The researchers recommend that there should be clear guidelines for extension of time known to all the major stakeholders of road construction projects in Ghana to contribute to the effective management of time claims within the road construction sector.

Keywords: Claims, Contracts, Extension of time, Road Construction, Ghana

Cite this paper: Dok Yen D. M., Odoom J. J., Assessing the Significant Factors Contributing to Extension of Time in Road Construction Contracts in Ghana, Journal of Civil Engineering Research, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.jce.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The success of a construction project can be measured using key parameters such as completion within schedule and allocated budget, whether the project was completed according to specification, whether the project meet the expectations of the client and the extent of variations (Khoshgoftar et al., 2010). It is believed that one of the top problems in the construction industry are delays (Jamil et al., 2012). Nevertheless, Buertey et al. (2012), attributed these delays to occurrences that might be caused by the client, the owner or an act of God. The risk of delaying completion of work is therefore borne by either the employer or the contractor and is usually allocated by the clauses covering an extension of time and liquidated damages in the contract (Tan, 2010). It must be noted that there are problems associated with the application and assessment of extension of time claims. In most instances, these problems lead to disputes which brings the entire project to halt. Danuri et al., (2006), attributed the problems with extension of time claims to lack of clear guidance in assessing claims. Road construction contracts in recent times have been characterized by claims of extension of time. Yusuwan and Adnan (2013b), cited a survey conducted by Waldron (2006) involving both public and private stakeholders of the construction industry which revealed that extension of time claims was ranked the third most disputed issue in the industry. Delays where the contractor is not at fault would normally constitute a valid claim for extension of time (Maritz and Prinsloo, 2016). Contractors often link delays to increased overhead costs as a result of a prolonged work period, increased cost of labour and materials due to inflation. (Assaf and Al-Hejji, 2006). However, lack of proper and transparent assessment of extension of time claims in the Ghanaian road construction industry has resulted in time and cost overruns on most road infrastructural projects. Although similar study was done by Amoatey and Ankrah (2017), by exploring on critical road project delay factors in Ghana. They failed to establish the Significant Factors that lead to extension of time within the Road Construction sector in Ghana, notwithstanding the numerous problems that are always associated with the application and assessment of extension of time claims in road projects. This study, therefore, seeks to assess the significant factors contributing to extension of time in road construction contracts in Ghana that will go a long way to contribute to the effective management of time claims at reasonable cost in the road contraction sector.

1.1. Overview of Road Construction Industry in Ghana

- Road infrastructure development is very important to the Ghanaian economy (Akomah and Jackson, 2016). Most urban and intercity transportation in Ghana is by road. In December, 2013 Ghana recorded a total road network of 68,156 kilometers, of which 13,367 kilometers were trunk roads, 42,189 kilometers feeder roads and 12,600 kilometers of urban roads (GIPC, 2018). The road networks provide inter-regional connectivity purposes, connect rural farming and fishing communities to nearby markets and serve as a link between Ghana and its neighboring countries. The institution responsible for policy formulation, coordinating and tracking the performance of the road sector is the Ministry of Roads and Highways. This ministry operates through the Ghana Highway Authority (GHA), Department of Feeder Roads (DFR) and Department of Urban Roads (DUR), (MOFEP, 2017). The Ghana Highway Authority is in charge of the administration, planning, controlling, and maintenance of trunk roads and its related facilities in Ghana. In a likewise manner, the Department of Feeder Roads is charged with the responsibility of administrating, planning, controlling, and maintenance of feeder roads and related facilities in Ghana. The vision of the Department of Feeder Roads is to provide roads which are accessible in all-weather at an optimum cost, which intend to facilitate the movement of people, freight and services in other to promote socio-economic development especially within the Agriculture sector. The vision of the department is providing reliable transport at a lesser cost to improve rural access to social facilities and services as well as employment opportunities most especially for women (MRH 2012). The Department of Urban Roads is charged with the responsibility of administrating, planning, controlling, and maintenance of urban roads and related facilities in Ghana. The urban road network provides all weather, city road access in support of the economic development taking place in all Metropolitan and Municipalities across the Country. The main sources of funding for road construction and maintenance are the Government of Ghana Consolidated Fund, the Ghana Road Fund and Donor Funds (Danida 2000). The consolidated fund is earmarked for development works, minor rehabilitation and upgrading. The Donor funds are channelled mainly toward maintenance and developmental works of huge financial volume. The road fund is dedicated to the maintenance of roads in general (MRH, 2012).

2. Extension of Time Claims

- As a result of the unique nature of each construction project (Chaphalkar and Iyer, 2014), and existence of complex interrelationships between a large number of parties involved in construction projects, claims in the construction industry is inevitable (Chaphalkar and Iyer, 2014). Claims have different sources, however, Chaphalkar and Iyer (2014) argue that delay claims are the most common. In line with this, Yusuwan and Adnan (2013b) have reported that an extension of time claims is inevitable and require effective management to ensure fair settlement.It is relevant for the contractor to produce an adequate document which absolves him from being responsible for the delay and gives evidence that other parties are responsible for the delay (Yusuwan and Adnan, 2013a; Alnaas et al., 2014). An extension of time claim must be accompanied by an analysis of the delay to quantify and demonstrate the time impact the delay has on the critical path of the approved work programme (Yusuwan and Adnan, 2013a). It is emphasized that the client is denied the use of the property by the earliest completion date, resulting in a loss of revenue (Fugar and Agyakwa-Baah, 2010; Clough and Sears, 1994). Furthermore, time overruns lead to additional cost of supervision. The Public Procurement Manual provides guidelines for dealing with delay claims in procurement of works contracts. Provision of extension of time renders a contractor not liable for liquidated damages if a delay is encountered. It is the responsibility of the Project Manager to indicate relevant clauses and the conditions attached to extension of time to deal with extension of time claims. Oyegoke (2006) postulate that the FIDIC conditions of contract clauses 6.3, 6.4, 12.2, 42.2 and 44.1 and Public Procurement Act (PPA) Conditions of Contract for medium sum works contract, Clause 28 deal with extension of time and reimbursement of any costs which may have been incurred by the contractor with regards to a delay by the employer. The clauses expressly provide that, extension of the intended date may be granted a compensation event occurs.

2.1. Factors Contributing to Extension of Time

- Delays which are not the responsibility of the contractor, often referred to as excusable delays, constitute the basis for extension of time in construction (Oyegoke, 2006; Trauner et al., 2009; Jamil et al., 2012; Yusuwan and Adnan, 2013b). Yates and Apstein (2006) as cited by Yusuwan and Adnan, (2013b) enumerated examples of excusable delays as force majeure, shortages of labour and materials, unavailability of required plant beyond the expectations of both parties, owner failure to give possession of the site to the contractor, change order, defective design and different site conditions. A study conducted by Jamil et al. (2012) in Pakistan into the analysis of time slippage for public sector projects revealed that, excusable delay factors encountered in project execution include inadequate funding, design changes, delay in approvals from statutory authorities, non-payments, late payments, change orders, suspension of work, inadequate design details at the start of the project, and change of government. These contribute to delays of a government funded project exceeding their completion time up to 100% coupled with significant cost overruns (Jamil et al., 2012). Similarly, Yusuwan and Adnan (2013b) in their study of issues associated with extension of time claim in a Malaysia construction industry, re-echoed these factors as causative agents in claims of extension of time. A number of extensions of time factors were also identified by Sambasivan and Soon (2007) in a study conducted in Malaysia. The key among them were mistakes during construction, lack of experience by contractor, delay in payment for work done, problems with subcontractors, labour shortage, unavailability of or breakdown of equipment, material shortages, poor communication between team members and poor site management by the contractor. In light of these findings, Gardezi et al. (2014) set out to investigate the most influential extension of time factors in Pakistan. The research revealed these ten (10) influential factors as follows; changes in design, war and terrorism, law and order situations, poor site management, political bureaucracies, currency inflations, delay in payments, inadequate funding by client and unrealistic project durations. There is an indication that the causes of delay claims found by a number of authors across the globe are not different from the situation in Ghana. Jackson and Akomah (2016) affirm to this by postulating that most of the delays in the road construction sector in Ghana could be attributed to unfavorable site conditions, delays in releasing funds, poor weather condition, changes in client orders, problems with assessing loans from banks, delays in honoring payment of certificate and delays by consultant in providing instructions. Yusuwan and Adnan (2013b) and Braimah (2013) indicated that most standard forms of contract across the globe adequately list out relevant events that allow a contractor to seek a time extension during the execution of the contract. The contract forms available for procurement of works in Ghana are of no exception. Clause 28 of the PPA Conditions of Contract for medium sum works contract stipulates compensations events that allow the contractor to apply for a time extension from the employer. Assaf and Al-Hejji (2006) in a survey conducted in Saudi Arabia to identify causes of delay in large construction projects, came out with a list of causes of delay of which change orders were the most common. Alnass et al. (2014), reported that, delays in issuing drawings, specifications and site instruction constitute compensation events which result in time extensions. The conditions of contract provide that, the prime contractor obtains approval of the project manager before the services of a subcontractor can be engaged. A study conducted by Khoshgoftar, et al. (2010), revealed that, despite the benefits of subcontracting, inefficient management can result in waste of productive time in the execution of contracts. Delays caused by the project manager in failing to approve a subcontract without a substantive reason would constitute fair grounds for an extension of time claim. Changes in ground conditions result in contract variations which are breeding grounds for monetary and time extension claims (Bio, 2015). Re-scoping of a road contract may occur as a result of prevailing unforeseen factors at the design stage of the project, changes in government policy and changes in client’s needs (Olanrewaju and Anavhe, 2014). Such delays often impact adversely on key factors of the project such as the project cost, completion time, and quality of work and safety of the project (Gardezi, et al., 2014). Several factors may occur during contract performance, such as sadden financial constrain, climatic condition, safety and security reason and so on that compels a client to order suspension of work, or a work stoppage (Cmguide 2017). In contract works execution, adverse weather conditions such as excessive rainfall may prevent the timely completion of the project (Alnass et al., 2014; Al-Momani, 2000). The complexity of civil engineering projects seems to suggest that, no contract can be executed without the occurrence of variations during the implementation stage (Bio, 2015). According to Fugar and Agyakwah-Baah (2010), bad weather is considered the most important delay factor by Ghanaian contractors in project execution. However, bad weather, is a natural phenomenon which parties to a contract have no control on. Delay in honouring payment certificates and other factors such as an underestimation of the costs of projects and underestimation of the complexity of projects, has been found by Fugar and Agyakwah-Baah (2010) as some of the leading factors affecting construction time.

3. Methodology

- Quantitative study was conducted within the road agencies in the Sunyani Metropolis namely; Ghana Highway Authority, Department of Urban Roads and the Department of Feeder Roads. Questionnaires were administered to management professionals consisting of quantity surveyors, contract managers and engineers. For this study. This was because these professions were responsible for managing the day to day road construction works within the metropolis.

3.1. Population of Study

- The target population for the study were management professionals of Ghana Highway Authority, Department of Feeder Roads and Department of Urban Roads in the Sunyani metropolis who are directly involved in procurement of road infrastructural projects. A total population of sixty-two (62) representing, managing professionals consisting of twenty-nine (29) Engineers, twenty-five (25) Quantity Surveyors, and eight (8) Contracts Managers were the respondents in this study.

3.2. Sampling Technique

- The census sampling technique was employed in this research due to small population size. In census sampling, data are collected on every member of the target population. This is an effective technique employed usually when the population is small.

3.3. Data Collection

- Questionnaires were distributed and retrieve from respondents in person. The research imbibed this method of distributing and collecting questionnaires as Ahadzie (2007) asserted that distributing questionnaire in person helps in making sure that questionnaires get to the intended respondents as well as increase the response rate. After the questionnaires were distributed, follow-ups were made to remind respondents to attend to the questionnaires. The follow-up were done through phone calls and visits. This strategy culminated in the high response rate of 100% questionnaires recorded.

3.4. Data Analysis

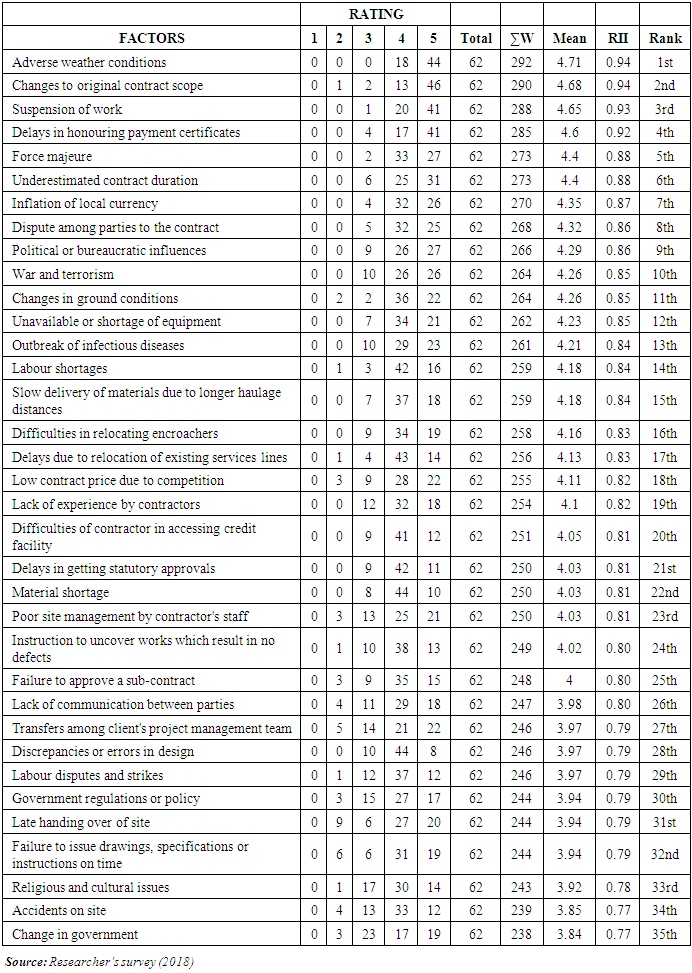

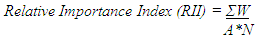

- The data gathered, that is the completed questionnaires, were analysed with the aid of the statistical software, Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS). Considering the design and numerous combinations of responses, the SPSS was the appropriate tool in simplifying and coding all the responses, and further generated basic statistical computations for the analysis. Responses from the retrieved questionnaires were coded with SPSS to make meaning out of the raw data gathered. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α) was employed to establish the scale reliability or the internal consistency of the survey data. Descriptive statistics were adopted to analyse the data which were further ranked with Relative Importance Index (RII) using the following formula;

Where:W’ means the variable weight, which ranges from 1-5 ‘A’ is the highest weight which is 5 ‘N’ is the total number of respondents which is 62After the analyses, the criterion with the highest RII emerged first indicating high importance and vice versa. Where two or more variables obtained the same RII, the variable with the higher mean value was ranked higher. One-sample test was also employed to test the significance of the ranked factors that contribute to extension of time.

Where:W’ means the variable weight, which ranges from 1-5 ‘A’ is the highest weight which is 5 ‘N’ is the total number of respondents which is 62After the analyses, the criterion with the highest RII emerged first indicating high importance and vice versa. Where two or more variables obtained the same RII, the variable with the higher mean value was ranked higher. One-sample test was also employed to test the significance of the ranked factors that contribute to extension of time.4. Analysis and Discussion

- This chapter presents the analysis of data analysis and discussion of the results of the study of the factors contributing to extension of time in road construction contracts in the Ghanaian. The descriptive statistics were conducted to establish the relevance of the items on the five-point Likert scale rating. Firstly, scale reliability test was performed to measure the internal consistencies of the data.

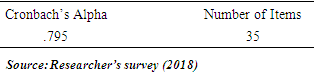

4.1. Reliability Test

- Reliability is concerned with the degree to which scores on a scale can be replicated. Thus, internal consistency reliability measures the reciprocal relation of an item set. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α) was employed in this research for testing reliability. According to Hair et al. (2010), a ‘α’ value of .70 or higher has largely been recognized by researchers as demonstrating a reliable measurement.

|

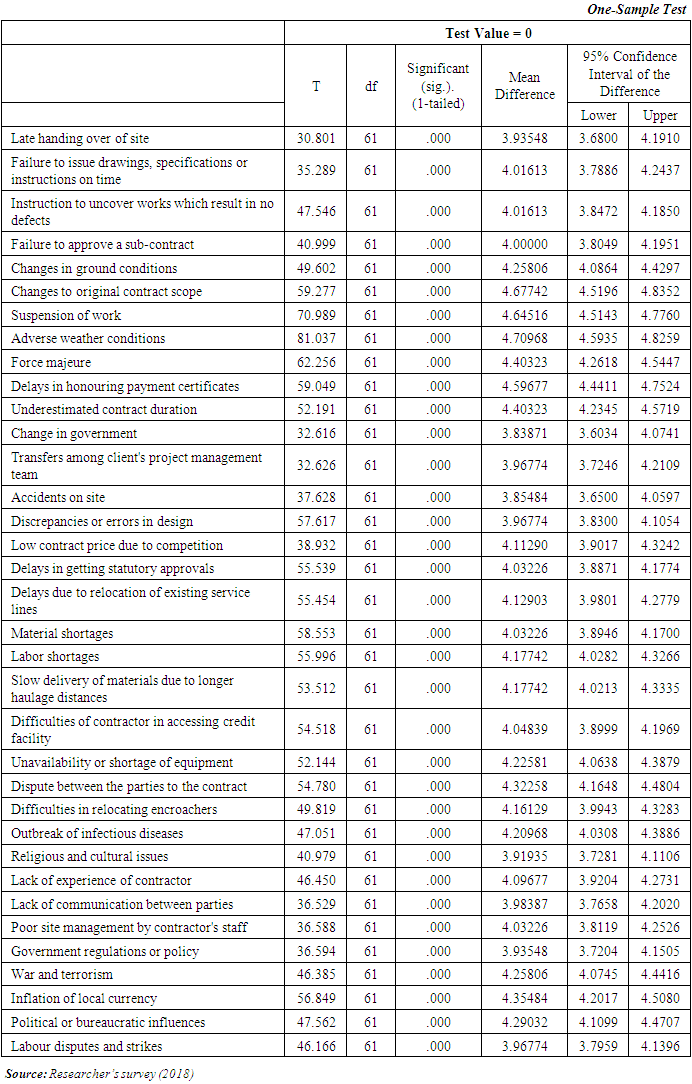

4.2. T-test

- Additionally, further tests were carried out on the factors contributing to extension of time to determine whether variables were statistically significant or not. The t-test on Table 2 shows the mean values of the population mean, t, which is the one sample t-test, Df, which is the degree of freedom and the significance (P-value). The p-value was used to establish whether the population mean and the sample mean were statistically equal or not. The p-value was divided into two because this study was interested in a single-tailed test, therefore, the p-values for two-tailed test was simply divided for the single-tailed test. The tests indicated that the entire thirty-five (35) variables were significant factors in contributing to extension of time. This explains why the significant column is .000 that is less than p-value (p < 0.001) for all the components.

|

4.3. Analysis and Discussion of Factors Contributing to Extension of Time

- The study in the quest to ascertain ways to enhance the management of extension of time claims in the road construction industry in Ghana. This section provides information on the analysis and discussion of respondent’s opinion on the significant factors contributing to extension of time in road construction contracts in Ghana. Respondents were asked to rank the variable factors contributing to extension of time Claims from their independent opinions to what extend they agree or disagree to the factors contributing to extension of time. The questionnaire was designed using a likart scale of 1-5 where 1= Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3= Neutral, 4 = Agree and 5 = Strongly Agree.

4.3.1. Adverse Weather Condition

- The adverse weather condition was established to Be the most significant factor contributing to the Causes for extension of time in relation to road construction projects in Ghana, with the highest Relative Important Index (RII) of 0.94 and a Mean value of 4.71. Weather plays an important role, especially in activities that has to do with construction which is normally undertaken in the open environment. According to Alnass et al., (2014); Al-Momani, (2000) adverse weather conditions such as excessive rainfall may prevent the timely completion of the project. Similar, Fugar and Agyakwah-Baah (2010) study also, revealed bad weather to be the most significant cause of delay to construction projects in Ghana. Furthermore, Oyegoke, (2006); Trauner et al., (2009); Jamil et al., (2012); Yusuwan and Adnan, (2013b) emphasised that adverse weather conditions, delays are the natural condition beyond the control of the contractor therefore, are not considered to be the fault of the contractor and often referred to as excusable delays, which often times forms the basis of an extension of time claims. Bordoli & Baldwin (1998) earlier study affirmed delays due to weather conditions neither to be orchestrated by the client nor should the contractor therefore be considered as excusable non-compensable. Hence, the contractor qualifies for an extension of time and is relieved from being liable to liquidated damages for the delay period without claim for cost compensation. Adverse weather condition is a major factor that contributes to extension of time claims in road construction projects in Ghana the results from this study is justifiable since no work could be adequately completed when there is heavy rainfalls.

|

4.3.2. Changes to Original Contract Scope

- The study further, revealed changes to the original contract scope to be the second most significant factor contributing to extension of time on a road construction project in Ghana, with the second highest relative important index (RII) of 0.94 and a Mean value of 4.68 after having been determined by a significant factor of T-test. Most road construction contract experience changes to the initial contract scope as the construction works progress and this contributes to extension of time claims.In a similar study, Bio (2015), shows that the complexity of civil engineering projects seems to suggest that, no contract can be executed without the occurrence of variations during the implementation stage. Gardezi et al. (2013) indicated that delays as a result of changes to the original contract scope more often have a greater adverse impact on key factors of the project in terms of project cost, quality of work and safety of the project. Furthermore, Olanrewaju and Anavhe, (2014) are of the view that the re - scoping of works usually occurs as a result of alteration of the original design by client’s, and this often requires the contractor to re-organize his resources and work schedules to address the alterations by the client within a new schedule date. This forms the basis for monetary compensation by the client. Oyegoke (2006), Trauner et al. (2009), Jamil et al. (2012) and Yusuwan and Adnan (2013b). Delay due to changes to the original contract scope is mostly the responsibility of the client, considered to be excusable and compensable to the contractor. Hence, contractors qualify for time extension as well as compensation cost.

4.3.3. Suspension of Work

- Suspension of work was considered to be the 3rd significant contributing factor to extension of time with an RII of 0.93 and mean value of 4.65 in road construction projects in Ghana. Suspension of time, usually occurs on a construction project when the employer requests the contractor by way of written instructions to temporarily stop work on all or a part of the project. In the Ghanaian contest the suspension of work in most road construction works is a very common phenomenon, especially where there is a change in political governance. Due to the fact that successive governments spend so much time to do due diligence by way of auditing and reassessing the award of roads contracts by their predecessors ongoing started by their previous government (myjoyonline, 2017). Earlier studies globally has revealed the suspension of works not resulting from the inability or fault of the contractor to be a legitimate concern for extension of time to the contractor, some of the reasons being that suspension of time significantly leads to time overrun. Enshassi et al. (2009), the study confirmed the suspension of time to be one of the major contributing factor to time overruns in during the construction in the Gaza Strip. However, it’s imperative to note that delay leading to suspension of work resulting from the client’s falls within the category of excusable and compensable delays (Bordoli & Baldwin 1998, Buertey et al. 2012). Hence, qualifies the contractor for extension of time and cost compensation.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The purpose of this study was to assess the significant factors contributing to extension of time in road construction contracts in Ghana. The problems associated with extension of time claims and its assessment most often leads to disputes between clients and contractors, which often brings road projects to stand still. From the study it can be seen that out of thirty five (35) variables contributing to extension of time for road contracts selected for the study within the Sunyani Metropolis, Ghana. Adverse weather conditions, changes to the original contract scope and Suspension of work were established to be the three (3) most significant factor contributing to the causes for extension of time in road construction projects in the Sunyani Metro. Therefore, in dealing with extension of time claim applications and processing within Sunyani, much consideration should be given to contractors with the above most significant factors contributing to extension of time. The researchers recommend that there should be clear guidelines for extension of time claims known to all the major stakeholders of road construction projects in Ghana, this would go a long way to contribute to effective management of time claims within the road construction sector as much as address the problems normally associated with extension of time claims in Ghana.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML