-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2025; 10(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20251001.01

Received: Dec. 28, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 19, 2025; Published: Jan. 21, 2025

Re-Engineering Coexistence in Syria- A Comparative Study

Mohamed Buheji1, Emmanuel Mushimiyimana2

1Founder, International Institute of Inspiration Economy, Bahrain

2Senior Lecturer, Socioeconomic Institute for Advanced Studies (SIAS), Rwanda

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji, Founder, International Institute of Inspiration Economy, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper examines the necessity of accelerating re-engineering the coexistence setup among the Syrian communities, using a comparative study and insights from Rwanda and South Africa. Given the historical divisions exacerbated by the Assad regime's policies, this study proposes a comprehensive framework for reconciliation based on qualitative comparative analysis. Employing a case study methodology, the research parallels Syria's socio-political context and the transformative experiences in Rwanda and South Africa. Findings indicate that recognition, forgiveness, and socio-economic equity are crucial for addressing the complexities of coexistence, ultimately contributing to a sustainable, inclusive Syrian society. Key strategies identified include establishing a national identity that transcends local affiliations, crafting an inclusive constitution, fostering a culture of tolerance, promoting sports as a unifying force, and integrating the diaspora into national rebuilding efforts. The authors aim to provide actionable recommendations for Syria to cultivate social cohesion and long-term peace in a post-conflict environment. Findings indicate that recognition, forgiveness, and socio-economic equity are crucial for addressing the complexities of coexistence, ultimately contributing to a sustainable, inclusive Syrian society. Buheji and Kakoty (2022).

Keywords: Coexistence, Syria, Post-revolution Reconciliation, Tolerance, Post-Conflict Recovery, Comparative Analysis, Social Integration, Ethnic Diversity

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji, Emmanuel Mushimiyimana, Re-Engineering Coexistence in Syria- A Comparative Study, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20251001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For a country like Syria, building coexistence among Syrian communities is a task that is necessary for country’s peace and development. One problem that prevents community development and peace at large is the absence of coexistence among community members. By taking insight from two cases in Africa: in Rwanda (after genocide against Tutsi in 1994) and in South Africa after the Apartheid regime, the authors propose a framework through which coexistence can be built in Syria after the devastating Assad regime. We find coexistence is needed in Syrian society after being torn by majority and minority divides, and now it is also thrown under threat through regional disparities, conflict over culture and resource distribution. Syria still has unset militias around the country, dissidents, and millions of refugees and thousands of displaced persons. Moreover, the country still has poor victims of the 14-year revolution against the previous Assad regime. Through this qualitative study, the authors assess how Syria needs to design and build its coexistence fabric among its citizens and communities. The study focuses on the thread that links this coexistence fabric together, including (1) the establishment of national identity that transcends local identities, regions and cultures; (2) setting new inclusive constitution that broadens the rights of formerly discriminated people, whether by majority-minority basis, gender, region, or religion; (3) building a culture of tolerance of the differences in culture and background and gradual change in the society; (4) taking sport and public event as a symbol of unity; (5) respect of minority (6) recognition and forgiveness; (7) building pragmatic justice and support of vulnerable and victims of war; (8) Demilitarization of society including reintegration camps of former combatant both inside and outside the country; (9) involving Syrian diaspora in national building process; (10) taking al-Jolani as symbol of unity and coexistence. Buheji (2018).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance and Priority of Coexistence in Syria

- Buheji (2020) emphasised that resilient communities can be built only if they are engaged in building the coexistence framework of the country. Coexistence towards unity is considered one of the essential plans for Syria to meet its prerequisite requirements that the international community and UN agencies expect to show clear efforts for peace and institutional reestablishment, El-Ferri (2024). Brys (2024) sees this as important for a country with challenges, such as Syria, which is based on factions related to religion, ethnicity, or tribes. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a well-engineered or re-engineered coexistence program that is socially constructed based on religion, tribes, political affiliations, and ethnic background.

2.2. Challenges towards Full Coexistence Program in Syria

- Only through creating resilient economies, can Syria navigate its strive towards growth and development while managing the high uncertainties, Buheji (2019b). Brys (2024) has seen that establishing a community of Syrians without identifying themselves as Sunnis, Kurds, Druze, Yazidis, Alawites, etc, has been and might continue to be a challenge due to years of civil war. Moreover, the country also has challenges in respecting the rights of minorities, besides the usual challenges in establishing coexistence among different tribes (Brys, 2024). The majority-minority groups in Syria are determined by religion, language, or culture, as well as the geographical location of the people (mountains, sea, cities, and deserts), Minority Right Groups (2025). These differences have characterised the aspects of conflict in Syria in one way or another. In terms of religion, Sunni Islam is estimated at the number of 75 per cent of the whole of Syria, Alawite Islam (12 per cent), and other factions, including Shiites and Durzee, are estimated to be within 2-3 per cent each. Christianity groups, including Greek Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Maronite, Syrian Catholic, Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic, are estimated to be within 10 per cent. Finally, the Yezidis are estimated to be within 1 per cent. Minority Right Groups (2025).The geographical space of the people in Syria has also been a cause of social cleavages (Minority Right Groups, 2025). There has been conflict between city dwellers, peasants, and Bedouins. The conflict between city dwellers and peasants is not negligible. In some cases, it may bring serious violence, as in the case of Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge forced around 2 million people from the city to relocate and bring them into the village by force compelling them to work there, and exterminated the city dwellers considered as “civilised” including Buddhists (Buheji and Mushimiyimana, 2023, p. 34). Even though the case of Syria is not like that, the regional cleavages cannot be neglected as they have been characterising the case of violence between communities (Minority Right Groups, 2025). The same situation applies to factionalism in politics, where the civil war left the country divided over proxy wars and political alignments, which fuel internal community divisionism, militarisation, and regional issues, Buheji and Hasan (2025). The country has influence from neighbouring regional powers, including Turkey, Russia, Iran, and Israel, in addition to the Western influence. Moreover, the country has been polarised by divides between those who supported former president Assad and the revolutionists, majority versus minority, cultural divides, regional disparities, etc. Therefore, building unity and coexistence requires bringing these social, political and geographical cleavages to the table and solving them. This paper aims to academically support this important step of building unity in Syria by elucidating its modus operandi and realising the complexity that was overcome in countries in Africa, such as Rwanda and South Africa.The theoretical framework on unity and coexistence exists basing three frameworks. The first is linked to the sense of building a nation and creating a homogenous culture, the second is linked to acceptance of heterogeneity and the creation of unity in differences, and the third is an assimilative approach that compels the dominant group to make the minorities look like for harmony. The case of Rwanda and of South Africa and Tanzania give us insight into how to build coexistence.

2.3. Road to Coexistence – The Rwandan Case

2.3.1. Realising the History of Divisions

- Rwanda, after the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, was in a dilemma of coexistence to the extent that some advisors wanted Rwanda to be partitioned into two parts – Hutu land and Tutsi land, the two major groups of ethnic identity that existed at the time. Rwanda has gone through various historical eras of bad governance characterised by divisions and discriminations based on ethnicity, religion, region of origin and nepotism, which have had devastating effects on its people’s social relations. Some of those effects include divisions, discrimination of all kinds, persecution, killings, exile of some Rwandans, war and Genocide against Tutsi. Therefore, Rwandans decided to fight any form of divisionism and discrimination that would also help to fight against genocide ideology in the future. In the Unity and reconciliation process of Rwanda after the 1994 genocide, most of the Rwandan people were aligned with their ethnic background, whether they were Hutu or Tutsi, or minority Twa. The dismantlement of institutionalised and culturally constructed ethnic groups since the colonial period was difficult. The implantation of hate and divide between Hutu as the majority population, which should otherwise use that principle to dominate other ethnic groups, were instrumentalised by Belgium to get rid of Kingdom leadership that they portrayed as Tutsi-dominated and also to create revolt against Tutsi ordinary citizen under majority principle of the so-called democratic majoritarianism”, Chua (2009). This majoritarianism triggered Hutus and others who were not initially Hutu but wanted to affiliate with the extremist government to take by force, burn and kill the Tutsi and subjugate and marginalise the Twa. Most of the Tusti were compelled to free the country in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, and they massively fled to Uganda, DRC, Tanzania, and Burundi in 1959. On the one hand, Tutsi were victims of Hutu power as it was the political and social slogan in 1990 to 1994 – a driver to the creation of political factions in line with the MRND, MDR and CDR parties that perpetrated genocide through MRND militia-trained by nationals and by foreign troops like France to kill Tutsi and moderate Hutu in Rwanda (Dallaire, 2004, AllAfrica, 2005). Dallaire (2004) argued that the naivety and irresponsibility of the international system and self-interest drove the Rwanda society to fall into extremism and genocide against Tutsi in 1994. Not only in Rwanda but also around the world, the society has been polarized over the issues of identity linked with different ideologies, religious affiliations, geographical space, race and ethnicity.

2.3.2. The Coexistence Framework that Sensitized Rwandans

- Rwanda's government set a framework that sensitised Rwandans at all levels to strive and value their unity by empowering the Rwandan community with the capacity to analyse their problems and find adequate solutions; the government also worked to promote a culture of peace based on trust, tolerance and respect for human rights. There are now programs that mentor Rwandans on patriotic values, actively playing a part in the governance of their country and promoting values existing in the Rwandan culture that contribute to the social cohesion and well-being of Rwandans. Buheji (2019a).Currently, this institutionalised identity before genocide eroded, and people call themselves Banyarwanda as a common national identity. Achieving this level of coexistence was framed in a unity and reconciliation policy, which started with a national dialogue and then the integration of the political elite into the political system, with the exclusion of extremists and former bearers of genocide ideology. This was followed by a consensual democratic move, economic distribution, demobilisation, and campaign of youth in the so-called “Ingando”, generally for 3-month paramilitary training for peace for the youth and justice policies. People were encouraged to unite and forgive. Unity and reconciliation among Rwandans are defined as a consensus practice of citizens who have a common nationality, share the same culture, and have equal rights. This reconciliation also emphasises that the citizens are characterized by trust, tolerance, mutual respect, equality, complementarity, truth, and healing of one another’s wounds inflicted by their dark history to lay a foundation for development in sustainable peace—Republic of Rwanda (2020).

2.3.3. The Rwandan ‘Social Resilience Approaches’ that Supported the Coexistence Framework

- The literature shows that after the 1994 genocide, Rwanda took a social resilience approach to avoid ethnicity by creating a homogeneous identity called “Ndumunyarwa” (I am Rwandan) (Gatwa and Mbonyinkebe, 2023, Buheji, and Mushimiyimana, 2024). To arrive at that point. To arrive at that point, Ndumunyarwada hinges on a pillar that violence would not happen again (Never Again) in Rwanda, correction of the teaching of violence and its historical prejudices, giving testimonies, healing, repenting, forgiving and healing from the wound of the genocide (REB, 2021). Moreover, Ndumunyarwanda gives trust and dignity to the youth and other Rwandans who were victims of former atrocities committed in the society and creates a new homogenous society without social cleavages on identity and region, an idea that was implemented in 2013 – 9 years after the genocide and social paralysis. The Ndi Umunyarwanda program teaches trust, tolerance, listening, humility, self-respect, helping each other, teamwork, and patriotism (REB, 2021). The program highlights taboos that are prohibited as far as unity and coexistence is concerned, including selfishness, betrayal of the country, hate, genocide ideology, and dissemination of hate to siblings and children (REB, 2024).The Ndumunyarwanda program also has a sustainable development aspect as it aims to decrease inequality among Rwandans, promote equal treatment, and bring a sense of togetherness for community cohesion. It also hinges upon the concept of dignity and self-reliance and reminds us that the survival of the nation in general and the community in particular hinges upon unity and coexistence. The concept of dignity and self-reliance compelled the country to establish Inama y’Umushyikirano (National Dialogue, which happens once a year). To discuss different challenges that can hinder the unity and development in Rwanda. It also helped Rwanda resist imperialism and neo-colonialism by focusing on Rwandan needs first: security, stability and coexistence. This was institutionalised as political and social organisations were prohibited from heavily and financially relying on foreign aid to avoid intruders and proxy wars. Besides, it facilitated the creation of Ibimina in rural and urban areas, financial institutions (SACCOs) at the sector level in both rural and urban areas, and development projects that reached remote areas without distinction of the region as it was before in the so-called Kiga (North) and Nduga (South). Ndumunyarwanda opened an opportunity to care for Rwandans abroad, setting the diaspora unit in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and inducing diaspora Rwanda Day abroad in which there is a reminder of Rwandan identity and call for diaspora members to participate in the national building. The campaign to induce reactiveness of the Rwandan diaspora started in 2009 with a One-dollar campaign to build orphan houses in Bugesera District and to sign different Cessation Clauses to end refugee status in different countries while encouraging Rwandans to repatriate. Rwanda also initiated values such as the establishment of Abarinzibigihango (the value of safeguarding people in different districts and regions). The role of these people is to showcase Rwandan role models of people who have helped others without tribal or ethnic distinction. Abarinzi big hang was one of the other homegrown initiatives taken by Rwanda, such as Abunzi and Inyangamugayo in the justice sector (Buheji and Mushimiyimana, 2024) to solve public injustices that happened and finish the culture of impunity in the community. In this institution like Inyangamugayo in Gacaca courts, justice was exercised in public once a week, and neighbours would openly judge any perpetrator and sentence him or her in front of the community; some of them were acquitted, and others were guilty and punished time half of their sentence would be to do public work. Raising up the household level of income, taking care of the life of people and establishing an economic working institution in the community increase the level of unity and coexistence. There is an association between wealth and health for community cohesion. The Rwandan government established Girinka programs and income generation activities to do so. It raised household take-home money for the poor or old persons depending on the income generation category. This is in line with the economic school of thought, which aims to establish wealth from the peaceful coexistence of the country (Collier, 2007). The economic policies primarily took Ndumunyarwanda as value to avoid the legacy of nepotism, regional factions and marginalisation of minorities. A culture that divided Rwandans, including negligence and insult to the minorities as well as excommunication of people due to their ethnic or religious background, was punishable by law. The establishment of a model village (imidugudu) mixed Rwandans without distinction and removed the exclusionary and segregation approach rooted in the past history. The country's progress to create a harmonious society has been institutionalized, legalized, civilised, and educated in schools for a new transformed Rwandan society.

2.4. Road to Coexistence – The South African Case

2.4.1. Realising the History of Divisions

- The post-apartheid South Africa since 1994 is another good case of building coexistence. The country was torn by the divides between white and black people, where the latter were marginalized by white-led government in their policy called “apartness” or “Separate Development”, Matthias (2024). The apartness policy was linked with the segregation of black people and economic discrimination, including lack of access to land, finance, and job opportunities that pay. The apartheid regime institutionalised discrimination to the extent that it was legal to locate one group and avoid another, as it was mainstreamed in the Population Registration Act of the 1950s. Separating whites from other races, such as blacks, Pakistanis and Indians, in terms of public and private advantages and also opportunities. The Group Area Act of 1950 was established to determine “residential and business sections in urban areas for each race, and members of other races were barred from living, operating businesses, or owning land in them—which led to thousands of Coloureds, Blacks, and Indians being removed” (Matthias, 2024). The city, like Durban, was exclusively white according to this act.

2.4.2. The Coexistence Framework that Sensitized South Africans

- Even though there is still a legacy of economic discrimination in South Africa, at least the Mandela government established coexistence since the end of the Apartheid regime in 1994. There are the rights of citizens regardless of race, even though blacks have until now been generally deprived of land as some white farmers still own a large portion of land at the rate of more than 80 per cent. In contrast, blacks and some poor families of white people live in slums, especially in the cities. Mandela’s government, however, managed to build coexistence among South Africans. The following are some of these strategies: (1) using sport as a factor of unifying the people, (2) creating a new identity of Africans despite being white or black, (3) using the idiosyncratic level of Mandela as a symbol of unity by his charismatic leadership after 27 years of staying in prison. In the 1995 Rugby World Cup held in South Africa, the nation took sport as one of the unifying factors of the country that transcended differences. This happened when Springboks, the South African rugby team, won the World Cup. There was only one non-white in the team, and rugby was considered as just white luxury by many blacks (Factual America (n.a). The presence of Mandela and congratulation of the Captain of the team and the whole team members was seen as a changing game to building a nation. Everyone congratulates each other for doing something for the nation. Since then, rugby has been considered a symbol of the South African nation (Factual America, N.A).

2.4.3. The South African ‘Social Resilience Approaches’ that Supported the Coexistence Framework

- The post-apartheid regime aimed to create a new identity in South Africa. Mandela's party wanted to integrate the smaller political parties into the system, and this was done. Moreover, the leadership claimed that everyone should feel the identity of South Africans and feel represented. Mandella achieved this by contacting community organisations, including Portuguese, Greeks, Jews, and Italians living and doing business in South Africa. and recognised everyone's effort to make peace and claimed that they should contribute to nation-building. His approach was based on cultural recognition and intercultural roles in building national unity and establishing a united government. In his ANC address in 1991, Mandela noted that his policy was not to establish a majoritarian democracy but rather a system that recognise minority groups as well. He recognises the importance of establishing a system that respects both the livelihood and rights of minorities (Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2025). In his speech, he claimed that not only blacks contributed to the struggle for liberation but even others, including “the Khoisan, the Bantu-speaking people, Coloureds, Indians and Whites, however few they might have been”. Moreover, Mandela recognised the elites that contributed to the struggle for liberation even though all were not ANC-winning party members, including: starting with the history of freedom fighters in South Africa, he mentioned Austshumays, Sheikh Abdurahman (Matebe), Maqoma and other pioneers of freedom. Among the parties, he recognizes the role of the Communist Party of South Africa, Cosatu, the PAC, Azapo, the Liberal Party and the Unity Movement, as they all produced political giants and young people of great potential. He also mentioned Sisulu, Mbeki, JK Zuma, Ahmed Kathrada, Mac Maharaj, George Peake from his party Robert Sobukwe, Zephanis Mothopeng, and John Pokela from PAC, and others from Azapo, Liberal Party, and the Unity Movement (Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2024).In terms of building social values that are necessary for coexistence, Mandela terms apartheid as a sin and calls for mutual respect between one another and for life. He also called for South Africans to fight against corruption and personal enrichment. Mandela also blamed people who evade paying taxes. No strike for personal interests; issues of unemployment and hunger should be solved first by individuals, including personal and family responsibilities through resilience, not strikes. To better coexist with others, people should be both healers and builders. South Africans had to deal with 5 million unemployed, enable a business environment and cut down the cost of production in order to sustain the job market (Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2025). As Mandela stipulated, the values of good conduct and avoiding family and domestic crimes were the cornerstones for building coexistence in South Africa. South Africa also pioneered in decreasing crimes after apartheid. “I expressed my delight to be back among them, but I then scolded the people for some of the crippling problems of urban black life. Students, I said, must return to school. Crime must be brought under control,” Mandela said. He also denoted that criminals should be contained and stopped from being called freedom fighters. “I told them that I had heard of criminals masquerading as freedom fighters, harassing innocent people and setting alight vehicles; these rogues had no place in the struggle. Freedom without civility, freedom without the ability to live in peace, was not true freedom at all,” said Mandela (Nelson Mandela Foundation 2025). The South African Police Service (SAPS) was established after the merger of South Africa Police and other apartheid police forces. The police system worked under a strict institutional checks and balances to prevent impunity, corruption, and revenge.Idiosyncratically, Mandela was in jail for 27 years but chose to be a peaceful political leader and avoided violence and revenge. This ousted the image of revenge in South Africa while taking South Africans, and the World symbolizing Mandela as their role model for peace and coexistence. In a nutshell, Mandela used the opportunity as leader of South Africa to awaken unity, solve community problems and personal problems as one’s responsibility and grab the opportunity to do good things in this world. These retrospective endeavours of South Africans enabled social cohesion despite the existing differences. In that way they managed to overcome divisive identities to create unity and racial, religious and cultural coexistence.

2.5. The Necessity of Coexistence in Syria

- There is a need to construct the unity and coexistence of Syrians. This is in terms of majority minority coexistence, religious mutual tolerance and coexistence, the ideological differences among political elites, and the general aspect of unity after 2024 revolution against Assad regime. In Syria millions of refugees are still abroad especially in America and europe, the political elites from Assad regime are in their homes and in the refuge, the police and army still around with a number of militia groups. There exist smaller militias and remnants of the former regime’s forces posing significant risks to civilians and even though active fighting has reduced in some areas, localized clashes and violence persist (Alio and Gardi, 2025). Almost one million person is displaced (Alio and Gardi, 2025). Syrian have been divided into majority and minority given the fact that inclusive social structure and governance were poor in the Assad regime. Most of the people are majority Arabs. However, there exist several groups of minorities, including Armenians, Turks and Kurds etc. They also speak different languages, such as Arabic (official), Kurdish (Kirmanji dialect), Armenian, Aramaic, Circassian, and Turkish. For coexistence, the consideration of these differences is paramount. Syrians also have religious differences, as most of the people are Muslim Sunnis, and 60 percent of them are Arabs. There are minority religious groups, including Eastern Christian Orthodoxy, Alawi Muslims, and Sunni Kurds. The minority population also includes Albanians, Bosnians, Cretan Muslims, Pashtuns, Persians, etc. Physical and human geography have been significant factors in the division of Syria’s social fabric, especially in the case of the city, desert, mountain and sea (Minority Right Group, 2025). Recently, social divides between town dwellers, peasants, and Bedouins and the conflict between the two have been significant in addition to religious differences and misunderstanding. The Druze people from South Syria have conflicted with both Muslim and Christian orthodoxy, and the culture of the cosmopolitan Mediterranean conflicted with the hinterlands’. Different from Rwanda, different groups of people live in their particular region, such as Syria. For instance, Alawi Muslims live in the Nusayri Mountain range in the coastal part of north-west Syria, but also on the inland plains of Homs and Hama, the Isma’ili Muslims live for the most part in the coastal mountain, south of the main Alawi areas. Twelver Shi’as live near Homs and to the west and north of Aleppo. The Greek Orthodox Christians and Catholics live mainly in Damascus, Latakiya and the neighbouring coastal region. Syriac Orthodox Christians are in Jazira, Homs, Aleppo, and Damascus, and Syrian Catholics are in small communities, mainly Aleppo, Hasaka, and Damascus. There is a small community of Maronite Christians in the Aleppo region.The Yezidis in Syria, currently mainly assimilated by Islam, live in Jabal Sim’an and the Afrin Valley in northwest Syria. There are several refugees from southern Türkiye but later also some from Iraq during the 1920s and 1930s, located mainly around Hasaka in the Jazira, north-east Syria, as well as Aleppo (Minority Right Group, 2025). There has been a brutal attack of ISIS against the Yezidi, causing some of them to flee their homes. Few Jews live in Damascus and Aleppo, and some settle in Golan Heights. One-third of Kurds live in the Taurus Mountains north of Aleppo and an equal number along the Turkish border in the Jazirah. Ten percent live in the vicinity of Jarabulus northeast of Aleppo, and 10-15 percent live in the Hayy al-Akrad (Quarter of the Kurds) on the outskirts of Damascus (Minority Right Group, 2025). Syria needs to consider the rights of minorities, including Armenians, Circassians and Turkomans, who live in different places, including Aleppo, Damascus and the Jazira. Moreover, Syria needs to stabilise the Golan stop the invasion of Israel in Golan and other foreign troops in that parts of the country and manage well the harmony of people with different refugees from neighbouring countries.

3. Methodology

- This study uses a comparative case study approach using the qualitative method. We have compared the cases of Rwanda and South Africa to compare and analyse what Syria can adopt to build coexistence after the 2024 revolution against the Assad regime. A synchronic comparison of the two cases gives impetuses to analyse the case of Syria and see the significant point in setting a sustainable community that can live together in peace, harmony and development. The theory of community coexistence and practices was highlighted to set up a coherent Syrian nation after 13 years of struggle and conflict.The epistemological approach used in this research is inspiration. This approach is about retrieving knowledge from other cases and designing a framework on how this knowledge can be reused for the betterment of societies globally and solving socioeconomic problems in communities. This occurs through reiterating best practices from successful communities and seeing how they can be a source of success for others (Buheji, 2016, p.18). In this case, Rwanda and South Africa's best practices of unity and coexistence can inspire Syria's post-revolution era.

4. Comparative Analysis of the Rwandan and South African Coexistence Experience vs. Syrians Essential Coexistence Needs

- The research finds nine strategies for coexistence in Syria based on a comparative analysis. These nine policies and actions have been retrieved from the cases of Rwanda after the genocide against Tutsi, the liberation struggle of RPF Inkotanyi, and South Africa after Apartheid.1st Priority- Establishment of a National Identity Program that Transcends Local Identities, Regions and Cultures. Syrian leaders may engineer a common identity as Syrian people that goes beyond former ethnic identities such as being Arab, Muslim, Christian, Armenian, Druze, etc. Similar to the experience of the Rwandans that helped to get rid of Tutsi and Hutu identities to embrace Ndumunyarwanda (I am Rwandan), this move may also help close the gap among Syrians. This approach may be done through ideological change teaching in leadership speeches, legal institutions, and political and community setups. For coexistence, the socialisation of this culture of commonness must be done, and community opinion leaders have to be trained and youth coached about it in the same ways in South Africa, where all associations and groups were involved. Rwandans even used Ingando and Itorero (teaching and training camps) to train and teach the youth about new policies of community coexistence for one to three months together.

| Figure (1). Represents an example of ‘Ingando’ solidarity camps where university students go for transformational civic education to coexist in Rwanda |

| Figure (2). Rwanda Diaspora Day in Washington with President Paul Kagame in the middle and kids dancing in front |

5. Proposed Framework for Re-Engineering Syria’s Coexistence

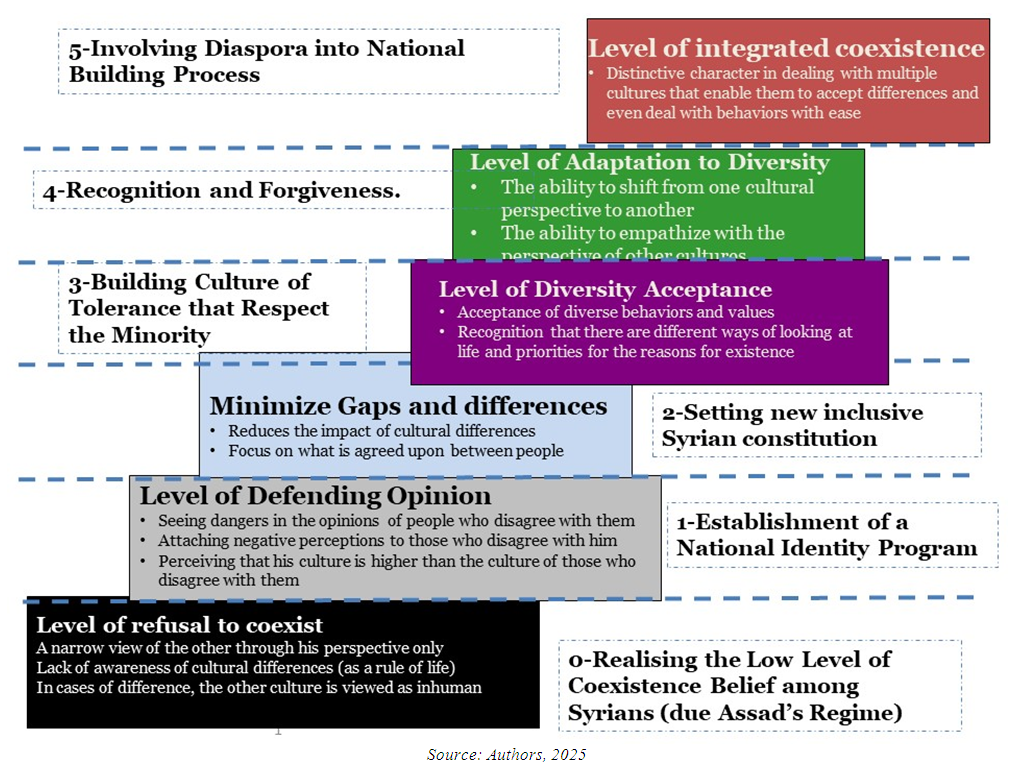

- There are different contexts in which society achieves the level of coexistence: either by accepting differences and creating a pluralist society or by accepting and aligning with the dominant group's status—assimilation. On one hand, pluralist societies accept their differences and accommodate them. The following Figure (3) highlights the level of coexistence, which induces the community members to accept living with differences and make coexistence from the level of refusal to live together to the ultimate level of accepting the differences at ease and living by accommodating behaviours.

| Figure (3). Proposed Syria’s Coexistence Development Scale and Framework |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- Fostering coexistence among Syrian communities is not merely a desirable goal but a critical necessity for achieving lasting peace and development in the country. This study highlights the importance of establishing a multi-faceted framework that draws on successful reconciliation experiences from Rwanda and South Africa. By implementing strategic priorities such as promoting a shared national identity, creating an inclusive constitution, and encouraging inter-community dialogue through sports and public events, Syria can begin to mend the fractures that have deepened over years of conflict. Moreover, recognising minority rights, facilitating justice for war victims, and actively involving the diaspora are essential steps toward building a more equitable and unified society. The journey towards coexistence will undoubtedly be challenging, requiring sustained commitment from leaders and community members alike. However, by embracing the principles of recognition, forgiveness, and mutual respect, Syria can pave the way for a future marked by social cohesion, resilience, and harmonious coexistence. Ultimately, these efforts will contribute not only to national healing but also to the broader stability of the region, positioning Syria as a model for overcoming divisions through inclusive and collaborative approaches.By using a comparative case study with inspirational epistemology. We concur that Syria's coexistence hinges on the following strategies such as creating a common identity for all Syrians, implementing unifying activities such as sports, ingando civic education camps, respecting and promoting the livelihood of minority groups, involving the diaspora, demilitarising the society, improving inclusive development projects and building practical justice, forgiveness and tolerance. The majority of Syrians have been trying to use an assimilative approach before, and some minorities are resisting the adoption of a pluralist society with respect to core unifying values. Abolishing backward culture in the society and in minorities can trigger inclusive Syrian socioeconomic development and enhance sustainable coexistence. This includes helping vulnerable groups, the poor, and victims of war.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML