-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2020; 6(1): 28-40

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20200601.03

Received: August 14, 2020; Accepted: August 20, 2020; Published: August 29, 2020

Cultural Planning of Dunga, Abindu and Kit-Mikayi Cultural Heritage Sites, Kisumu City, Kenya

Fredrick Odede1, Patrick Hayombe2, Stephen Agong’3, Fredrick Owino2

1School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Jaramogi Oginga Oginga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2School of Spatial Planning and Natural Resource Management, Jaramogi Oginga Oginga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

3School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, Jaramogi Oginga Oginga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Fredrick Odede, School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Jaramogi Oginga Oginga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study aimed at undertaking data collection on cultural planning of cultural heritage destinations of Dunga, Abindu and Kit-Mikayi sites in Kisumu City for sustainable utilization, and management to support urban local livelihood. The study was done at four selected cultural heritage sites in Kisumu city of Kenya on the Eastern shores of Lake Victoria. The study objectives included to carry out data collection on potential development threats to the cultural heritage elements and values at these destinations; To undertake site conditional surveys for situation analysis and mapping of the threats at specific sections of the sites; To develop planning and management strategies for the heritage sites and: To develop site cultural planning strategic policies for these heritage sites. Social identity theory steered the study for in-depth exploration of the subject matter. Collection of data involved oral interviews, observation and focus group discussions with the various respondents who have interest in the cultural heritage sites. Site conditional surveys were useful in the assessment of the sites’ physical conditions. The study findings suggests that in order to make cultural heritage promotion and planning in Kisumu sustainable and more appealing to domestic and international tourists, some strategies were proposed to be adopted. These included collaboration among stakeholders, the promotion of attractive cultural heritage tourism products through a co-production process, planning and conservation of Kisumu city’s cultural and historic resources. Due to its very nature, cultural heritage planning for sustainable growth requires effective partnerships. Therefore, there is need for local communities, NGOs, Kenya’s government, county government and development partners to work closely together in order to develop robust and sustainable cultural heritage promotion that can make a community a better place to live as well as an attractive cultural place destination.

Keywords: Cultural planning, Cultural heritage, City, Sites

Cite this paper: Fredrick Odede, Patrick Hayombe, Stephen Agong’, Fredrick Owino, Cultural Planning of Dunga, Abindu and Kit-Mikayi Cultural Heritage Sites, Kisumu City, Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2020, pp. 28-40. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20200601.03.

Article Outline

1. Background Information

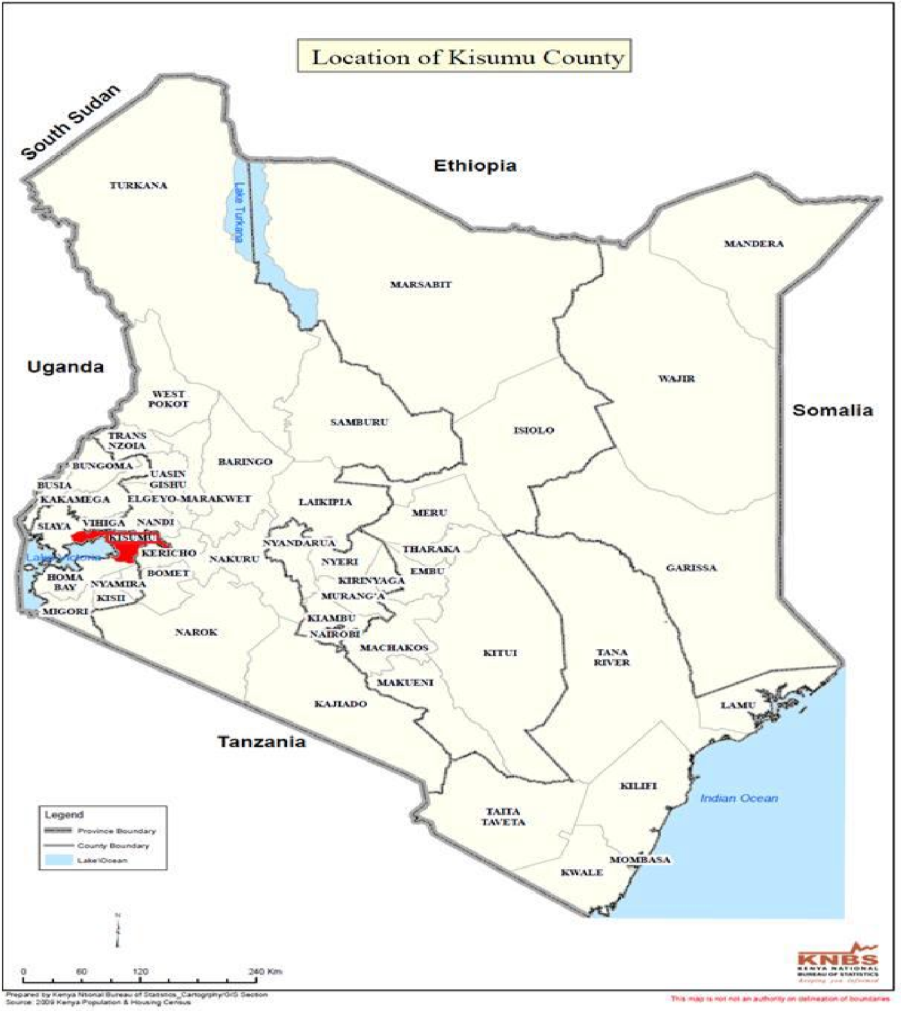

- The code of ethics promoting the highest standards of practice in regard to cultural heritage has been with us for over 50 years. The first attempt to promote such principles occurred in 1931 during the Athens Congress on restoration of historic monuments (Athens Charter, 1931; UNESCO, 2006; ICOMOS, 2011) that produced the principles guiding the preservation and restoration of ancient buildings to be applied by each country within the framework of its own culture and traditions.Cultural heritage may be defined as things, places and practices that define who we are as individuals, communities, nations or civilizations. It is that aspect of our lives or environment which we want to keep, share and pass on to future generations (Onjala, 2011:79). In essence, tangible cultural heritage are the sites, monuments and objects. Intangible cultural heritage are the values, norms, traditions, folklore, Music and dance, traditional skills and technologies and the meaning a society derives from them and perpetrates for posterity (Fielden & Jakilehto, 1998:5). Culture is a way of life relating to habits, traditions, and beliefs of a society (Good, 2008). Heritage is property that is inherited, or valued things such as historic buildings that have been passed down from previous generations. UNESCO has been the world’s most important institution responsible for the management, conservation and promotion of cultural and natural heritage sites, as well as, the establishment of various international conservation charters. Cultural umbrella has played a significant role in presenting to the general public various cultural properties of outstanding universal value from all corners of the world since its establishment. It has brought together heritage professionals with divergent views and cultural experiences to share and exchange ideas and work together during workshops, seminars and training programmes (UNESCO, 1985). Kenya’s cultural heritage tourism, as well as, present and future growth will be based on ecotourism as a key pillar for transformation within the emerging opportunities in the digital century. Ecotourism is futuristic and based on key resources of ecological integrity and cultural identity that is prominent within the Lake Victoria region, which has been described as a virgin and unexploited touristic destination in the Western Tourism Circuit (Hayombe, Odede, Agong, & Mossberg, 2014). Lake Victoria tourism destinations are numerous and include Ndere Island, Dunga, Kit Mikayi, Luanda Magere, Seme-Kaila, Thimlich Ohinga, Fort Tenan, Jaramogi Oginga Mausoleum, Tom Mboya Mausoleum, Got Ramogi, Gogo Falls, Sarah Obama Cultural Centre, Wadh Lango, Muguruk, Simbi Nyaima, Kanam and Kanjira, Rusinga Island, Nyamgodho, Ruma National Park among others (Hayombe, 2011). In Kenya, as in any other countries of the world, cultural heritage is considered as irreplaceable source of spiritual and intellectual riches of all human kind. It is a source of history, identity and life. Monuments, sites, shrines and other sacred places reflect complex cultural heritage diversity with values emanating from all aspects of belief systems (Odede, 2007). The National Museums of Kenya (NMK) is a state corporation established by an Act of Parliament, the National Museums and Heritage Act Chapter 216 of 2006, Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 63 (Republic of Kenya, 2009). The study aimed at undertaking data collection on cultural planning of cultural heritage destinations of Dunga, Abindu and Kit-Mikayi sites in Kisumu City (Fig. 1) for sustainable utilization, and management to support urban local livelihood, and community empowerment initiatives. Cultural planning also aimed at the conservation and sustenance of cultural heritage integrity and authenticity in the face of modernization and the ever-rising tourism visitor numbers at these cultural heritage sites posing a threat to their very existence. Cultural planning was supposed to upscale income generation to support local livelihood for sustainable urban growth of Kisumu City based on cultural policies and actions towards the sites. Kisumu City boasts of diverse cultural heritage resources that are uniquely and spatially distributed on the landscape laced with scenic landforms that traverse the city and its environs. As one moves across the city into the Lake Victoria shores a myriad of cultural and natural features as well as artifacts dot this unique lacustrine region of western Kenya.

| Figure 1. Location of Study Area in Kenya, Source: GoK, 2009 |

1.1. Theoretical Framework

- Many studies on cultural heritage have used Social Identity Theory as the theoretical framework (Rubin & Hewstone, 1998; Abrams & Hogg, 1990). Social identity theory postulates that when an in- group identity is made, people often wish to emphasize characteristics of their group that they value (Stets & Burke, 2000). The theory suggests that by expressing its distinctive characteristics, people can thereby assume unqualified pride in their membership in this group. Moreover, the theory suggests that public identification with the group translates into a greater sense of personal worth. This theory is relevant to the cultural planning situation in Kisumu county, Kenya. According to the theory, the host communities identify with the cultural heritage sites in their locality helping them to classify themselves as members of the same in- group, with their cultural heritage being the unifying factor.

1.2. Research Objectives

- i. To determine potential development threats to the cultural heritage elements and values at these destinations.ii. To undertake site conditional surveys for situation analysis and mapping of the threats at specific sections of the sites.iii. To examine the frequent challenges facing the sites as a whole for possible mitigation purposes.iv. To develop planning and management strategies for the heritage sites.v. To develop site cultural planning strategic policies for these heritage sites.

1.3. Research Methodology

- The study areas were Dunga, Abindu and Kit-Mikayi heritage sites. Collection of data involved oral interviews, observation and focus group discussions with the various respondents who have interest in the cultural heritage sites. Site conditional surveys were useful in the assessment of the sites’ physical conditions to examine the challenges and threats facing each of the sites. Photography of the affected areas by various factors and activities as well as visitors’ impacts on the sites was also undertaken. Focus group discussions generated information on general challenges and specific threats to the sites as well as possible mitigation strategies or solutions for corroboration or triangulation with other sources of data. The development of cultural planning and management strategies formed the policy frameworks useful for implementation by the site management team and the county government for site management and conservation of these destinations for posterity in Kisumu County.

2. Results/Research Findings

2.1. Cultural Heritage Sites Situational Analysis

- Dunga Beach and Wetland is known for its unique eco-cultural attractions due to its biodiversity and cultural rich and diverse papyrus wetland ecosystem and local community respectively. Dunga swamp is an Important Bird Area (IBA) - place of international importance for bird conservation covering 5000 ha located at Dunga at the Tako River Mouth, a wetland situated about 10 km south of Kisumu town on the shores of Winam Gulf Lake Victoria. Eco - finder Kenya has established Dunga Wetland Pedagogical Centre at Dunga Beach as a grass-root led intervention whose overarching cardinal goal is empowerment of Dunga Wetland Community and improvement of livelihood security of its people. Therefore, some of the main focuses in the center are promoting Eco-Cultural Tourism and facilitate the conservation of the Dunga Papyrus Wetland Ecosystem.Abindu is a Luo word that means caves in one place. Abindu Sacred site was inhabited by the Kipsigis community as far back as 500 years. From oral narrative, it is said that the Luo drove away the Kipsigis from Abindu area to their present settlement in the Rift Valley. As the Luo migrated from the main area of dispersal at Got Ramogi Hill, different cultural groups moved into the Winam Gulf and Abindu was used as a fort by different migrant groups such as the Luo, Kipsigis, and Luhyia to ward off their enemies during the occupation and settlement of the region.Seme-Kaila site was inhabited by the Kipsigis community as far back as 500 years. From oral narrative, it is said that the Luo drove away the Kipsigis from Seme-Kaila area to their present settlement in the Rift Valley (Ochieng, 2013). As the Luo migrated from the main area of dispersal at Got Ramogi Hill, different cultural groups moved into the Winam Gulf. Seme-Kaila enclosures were used as forts by different migrant groups such as the Luo, Kipsigis, and Luhyia to ward off their enemies during the occupation and settlement of the region (Ochieng, 2013). Oral information indicated that Seme-Kaila enclosures were built and occupied by the direct ancestors of Seme people who are the current occupants of the area. Oral information indicates that the names of the individual enclosures are drawn from the names of the sons of Ogutu who was the leader of the Luo clan that migrated and settled on Kaila hill. The sons were Ojil, Atito, Odiaga, and Aol. The migrants later built the settlement enclosures to act as defensive mechanisms against external human foes and wild animals from attacking their occupants. The enclosures were easily built due to availability of loose surface rocks that reduced the transportation cost during the construction. Communal lifestyle at that early time enabled acquisition of cheap labour for the construction of the enclosures. During the settlement period, the highland Nilotes were moving around the region, engaging in constant raiding of their neighbours for cattle and land. Inside the enclosures, huts were aligned along the walls with the huts of the sons of the family situated next to the gates to watch any advancing enemy and guard the fortified settlements. Several families used to live in one enclosure for security reasons and close bond between family members due to communal lifestyle. High level of awareness of the occupation of the site shows close relationship between the builders of the enclosures and the host community at Seme-Kaila. Another version of oral information stated that the enclosures were built by the sons of Ogutu who are the ancestors of the present inhabitants of the area. All the gates used to face the western side of the enclosures. The gates were facing the opposite direction of the enemy’s route to spot human foes in case of external aggression or attack. High awareness of the use of the site for settlement shows close relationship between the enclosures and the present residents of the area. The enclosures were built by the sons of Ogutu who built the enclosures for protection and defense. The enclosures were initially covered by a dense thick forest where wild animals roamed. The vegetative cover used to be that of indigenous plants, namely, ‘siala’, ‘ngowo’, and ‘oseno’ just to mention a few. The indigenous vegetation has, however, been cleared by cultivation, and due to expansion of human settlements. The names indicate a sense of ownership by the host community which is useful in motivating the community to participate in the preservation of the prehistoric settlements as testimony of the community’s origins and land ownership claims to the future generations (Onjala, 2011). Associated archaeological material remains in Seme enclosures are of Luo in origin further indicating the community’s attachment to the site (Wandibba, 1986; Herbich & Dietler, 1989). Other material remains found in the site include beads, grinding stones and remains of house platforms at Seme-Kaila that the host community feel should be preserved for the younger generation which conforms to cultural conservation propagated by Goma (2007). Despite the high level of individual willingness to participate in site activities, the community continues to be the main agent of site destruction possibly due to lack of knowledge on the ecotourism benefits of the site, as well as, lack of exposure to similar cultural heritage sites with proper management and conservation efforts in place.

2.2. Cultural Heritage Sites Values

- Cultural tourism currently exists within Dunga beach. The respondents were able to identify the products available at Dunga; what they offer; the products that are yet to be exploited or promoted, potential of Dunga beach to the community in terms of social, environmental and economic benefits; and if cultural heritage at the beach can benefit them individually. The cultural tourism benefited people personally through income generation and employment creation. On its potential, Dunga had: basketry, fish festival, bird watching, hippo watching, and boat riding, Kalanywena (sport crocodile), sport fishing, and rowing competitions. The Scenery to be exploited for the beach included: Dunga–water sport, traditional dances, homestead, storytelling, and camping facilities (Plates 1 and 2).

| Plate 1. Dunga Beach in Kisumu City |

| Plate 2. Wetland birds at Dunga beach, Kisumu |

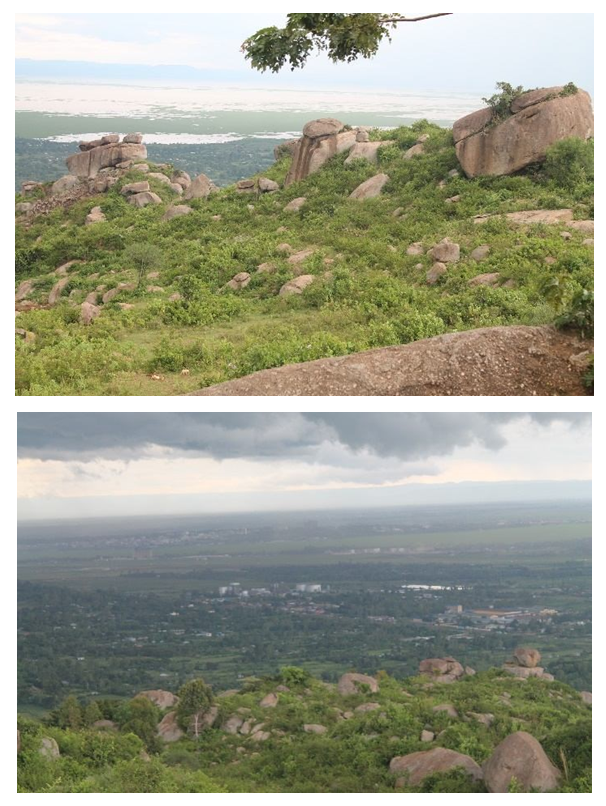

| Plate 3. Beautiful Landscape and view of Kisumu City from Abindu sacred site |

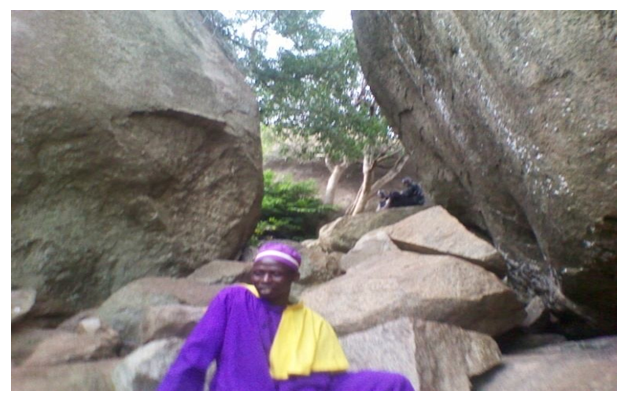

| Plate 4. Sacred value of Abindu site |

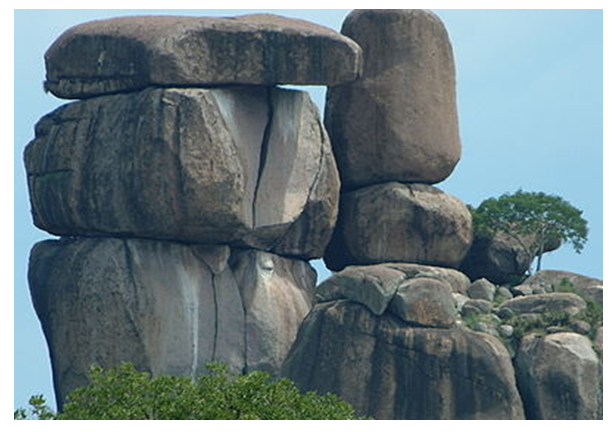

| Plate 5. Kit-Mikayi rocks/sacred site |

2.3. Potential Threats and Challenges facing Heritage Sites

- During oral interviews, focused group discussions and field observation, the research came up with key challenges affecting the management, utilization and promotion of the sites for cultural planning purposes. Some of the challenges or threats identified in each of the sites are as follows:Dunga has some foreseen challenges for collaboration namely: Poor roads as they are not tarmacked thus hindering tourist to access the area and affecting the rate at which people access the license and permits; Negative publicity though negative talks concerning the site is a hindrance; Insecurity which hinders tourist from accessing the sites; lack of Peoples’ good will- People around should be sensitized about the site to enable them know unhygienic waste management, tourist sites enrichment in the site, lack of professionalism in the site, lack of human animals conflicts where the human kill the animals for food; Language barrier- where by the tourists have to communicate to the locals through a translator; Habitat Destruction-the locals destroying the site knowingly or unknowingly; Drug and Alcohol Addiction due to unemployment and failure to take responsibility by individuals.At Abindu, visitation to the site is still hampered with impassable rural access roads that lead to the site during the wet rainy seasons in the region; Abindu has remained unknown globally due to poor infrastructure, insufficient networking and lack of international collaboration, low level of literacy and lack of awareness of its cultural and touristic value have deprived Abindu from being a great world tourism destination; Business opportunities have not been exploited with limited community engagement in eco-ventures; The site has wild animals like monkeys and baboons that are a menace to neighbouring farms and is source of human-wildlife conflict. Human wildlife conflict is common especially where communities are not allowed to harvest dead wood for firewood. Large reptiles such as snakes (python, black mamba, cobra, puff adder) sometime cause harm to the people living within the site environment. There is human-wildlife conflict since most of the animals feed on crops cultivated by the community around the site; Community participation in the management of the cultural heritage is motivated by empowerment and employment concerns, which are currently lacking at the site. This is a threat to sustainability of the cultural heritage site and its conservation for posterity; Accommodation facilities are lacking within the site environs since no lodge has been constructed and most visitors have to get back to major urban centers; The community feels neglected and divorced from their heritage because few of them have been employed or given any economic rewards despite the numerous visitors that come to the site; Lack of organized youth groups to participate in cultural and natural heritage conservation and management as well as site branding; Lack of proper branding and image creation of the site to upscale ecotourism visitation to the site. The site has no signage, posters or brochures to attract visitors. Kit-Mikayi sacred site is faced with human encroachment as a result of farming and human settlement activities. The numerous religious groups that frequent the site leave behind litters and remains of burnt offerings used during prayer sessions. The rock itself is undergoing physical disintegration or decay through biological and physical weathering processes thus weakening the rock component of the site. Land carrying capacity as a result of the numerous visitors against limited space available poses a threat to the existence of the cultural heritage site. Lack of skilled and trained personnel in heritage management among the CBO members is a challenge to its management. The distortion of the oral narratives regarding the site’s history, which is tied to family history of some members of the management team is a problem. Lack of information centre and exhibition space has affected appropriate dissemination of information and limited visitor experience. Funding is the major challenge, followed by poor implementation of heritage conservation and marketing policies as well as inadequate trained personnel to help in the management of the heritage sites. In order to overcome these challenges, various strategies have been developed, for example ecotourism activities that involve communities around the sites so as to improve their livelihood, and generating income through other means such as fund- raising and corporate sponsorships and architectural competitions. The entire sites CBOs indicated that the Ministry of Sports, Culture and Heritage and the Kenya Tourism Board must work together with all the cultural sites in the country so as to help market their products to a wider domestic and international tourist market (Irunda & Shah, 1976).Insufficient funding is another critical problem that results in lack of protection, interpretation and adequate visitor management. Cultural heritage conservation puts demands on infrastructure such as roads, airports, water supplies and public services like police and firefighting forces. This has been found to be a common problem throughout the world, but it is more serious in developing countries where public funds are scarce. Rapid urbanization in the developing world, including Dunga beach in Kisumu City of Kenya, also tends to push historic properties down the priority list a similar experience as put forth by Bandarin, and Ron van Oers (2012). In other words, governments in developing countries such as Kenya and Kisumu County tend to support urban development rather than conservation of cultural and historical resources. The crippling poverty of the majority of the population in the region makes them more interested in basic survival than conservation of cultural heritage (Deisser & Njuguna, 1976).Seme-Kaila site faces challenges such as site destruction as a result of quarrying activities, human encroachment due to farming and settlements, lack of trained and skilled personnel in heritage management, soil erosion, animals trampling on the stone-walled enclosures, low level of community interest into the historical sites leading to over-grown vegetative cover, lack of marketing and branding initiatives, inadequate funds for site improvement, lack of social and infrastructural facilities and limited access to the site.

| Plate 6. Enclosure Wall with overgrown vegetative cover at Seme-Kaila (Source: Author, 2014) |

2.4. Cultural Heritage and Relevant Planning Policies

- Formulation of cultural heritage laws in Kenya has borrowed heavily from European concepts of the protection of cultural proper laws on the protection of cultural heritage that included provisions relative to the definition of cultural property. Such provisions define ownership and usage systems; the scope of protection required for these systems; regulate archaeological excavation and chance discoveries; indicate the authorities and bodies charged with the protection and consequently application of these legal provisions. Protection of cultural property includes activities such as cataloguing, recording, listing, and declaring heritage items as important publicly. It also includes respecting the rights and obligations of the owner, holder and public agencies that have links to the protected items and lastly, ensuring safety of the items by controlling trade involving such items. The Ancient Monuments Preservation Ordinance of 1927: The first documented legal framework in Kenya for the preservation of monuments and objects of archaeological heritage, repealed in 1934, enacted by Governor of the Colony. Provided for the preservation of ancient monuments and antiquities; the exercise of control over excavations in certain places, and the protection, acquisition of ancient monuments and antiquities, as well as, items of historical, archaeological, or artistic significance did not provide for institutions in the protection, management and preservation of monuments and antiquities. Instead, it provided for individual-based protection, management and conservation of monuments and antiquities.The Antiquities and Monuments Act (Cap 215) and the National Museums (Cap 216) of 1984: Enacted primarily to oversee the operations of the NMK in order to ensure that proper standards of management of heritage were maintained, but was heavily borrowed from colonial masters. Cap 215 of the Laws of Kenya was conspicuously silent about the role of NMK in heritage management and ambiguously gave the responsible minister the powers to gazette cultural properties as national monuments, concern that the law was not adequate in addressing AHM challenges, thus the Act was repealed in 2006 and the National Assembly of Kenya enacted National Museums and Heritage Act Bill of 2006. National Museums and Heritage Act, 2006: Currently, the official organization mandated by the Government of Kenya to protect, preserve and control the use of Cultural Heritage in the country that operates under the National Museums and Heritage Act 2006. The Act was ratified by the National Assembly of Kenya in August, 2006 to repeal the then Antiquities and Monuments Act Cap 215 and the National Museums Act Cap 216. The 2006 Act herein cited as The National Museums and Heritage Act, 2006 with commencement date of 8th September, 2006 is an Act of Parliament meant to consolidate the law relating to national museums and heritage. It provides for control, establishment, development and management of national museums and the protection, identification, transmission and conservation of the natural and cultural heritage of Kenya.Constitution of Kenya 2010: Saw the creation of decentralized governance system (GoK, 2010). Under Article 176 of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, County Governments were created and among its autonomous functions, is the mandate of planning at their respective jurisdiction. Counties were thus mandated to ensure integration of economic, physical, social, environmental and spatial planning in their operations (GoK, 2012). Therefore, it is within the county spatial planning framework where cultural heritage sites and the challenges they are facing can be addressed. Decentralization of planning functions to the county level provides a suitable framework for holistic development of policies and plans to spearhead sustainable development of cultural sites. Additionally, the Physical Planning Act cap 286 of 1996 which has since been repealed mandated that preparation of plans must secure appropriate provision for transportation, commercial, public purposes, utilities and services, residential, industrial and recreational areas, including open spaces, parks and reserves. Cultural heritage sites in Kisumu are recreational places for visitors to these destinations, and qualify as public open spaces that provide social services and other infrastructural needs that should be planned for proper management and service provision to the tourists as well as the host communities.The Urban Areas and Cities Act 2011: Is a legislation of parliament formulated to provide for the organization, administration and governance of urban areas and cities; to provide for the standards of establishing urban areas, to provide for the governance and involvement of residents (GoK, 2011). Cultural heritage sites are thus covered by the framework of this Act. Particularly, residents must be given an opportunity to deliberate and make proposals for enhancing quality of environment within which they operate. Physical and Land Use Planning Act 2019: Provides for the guidelines of development control whose objectives are: to ensure orderly physical development; to ensure optimal land use; to ensure the proper execution and implementation of approved physical development plans; to protect and conserve the environment; to promote public participation in physical development decision making; and to ensure orderly and planned development, planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance. The lack of enforcement of development control mechanisms in the cultural heritage sites achieves an undesired state of physical development which is coupled with poor infrastructure, lack of services and fragmented land uses. Environmental conservation and protection of the vicinity of cultural objects was useful for maintaining the authenticity and integrity of the sites under study in the face of modernization, and urbanization processes. Physical Planning Handbook (2008): Provides guidelines and standards on the process and practice of physical planning. It recognizes that cultural heritage sites have become an integral part of the urban scene and can no longer be ignored. Further, it ascertains that cultural sites are considered as special features in planning. Location of these sites is influenced by ease of accessibility hence a significant feature for planning for site signages for visitor directions at the site and development of other trigger off infrastructural developments like water, electricity, foot-paths and sanitation facilities (GoK, 2008).

2.4.1. Heritage Management Policies

- UNESCO has been the world’s most important institution responsible for the management, conservation and promotion of world heritage sites, as well as, the establishment of various international conservation charters. This world cultural umbrella has played a significant role in presenting to the general public various cultural properties of outstanding universal value from all corners of the world since its establishment. It has brought together heritage professionals with divergent views and cultural experiences to share and exchange ideas and work together during workshops, seminars and training programmes (UNESCO, 1972). However, the policies for the protection of archaeological heritage are outlined in the ICOMOS Charter (1990) which constitutes the basic foundation of the principles of Archaeological Heritage Management (AHM). It posits that principles should be integrated into planning policies at international, regional and local levels. The process of AHM involves identification, interpretation, maintenance, and preservation of significant archaeological sites and physical assets. AHM receives most attention and resources in the face of threat. Possible threats include urbanization, large-scale agriculture, mining, prospecting, theft, and uncontrolled tourism. AHM can be traced back to the rescue archaeology and urban archaeology undertaken throughout North America and Europe in the 1st half of the 20th Century.The management of threats facing AH in the world would follow a well-defined system of actions and protocols guided by internationally accepted regulations. System of action and protocol advanced for AHM by party states constitutes its policy framework in a country. Policies are meant to organize, regulate and ensure good practice and they are enforced by legislation.The policy statements should take into consideration inspirations, interests and values of the people for which protection and conservation is meant to serve. The primary methods by which state heritage authorities are given power to intervene in management of heritage resources is by instituting protective measures, taking control of heritage by means of acquiring title thereto, or by instituting punitive measures.Culture and Heritage Management policy is a step towards ensuring a future for the cultural legacy. Policies simplify the existing laws and offer guidance on how best the heritage should be conserved and managed. In a nutshell, policies are a necessary prerequisite for any meaningful Heritage Management effort. A platform set by ICCROM requires the said policies to be curative.Heritage management in Kenya was weighed against internationally accepted standards as outlined in the ICOMOS Charter of 1990. The aspects of AHM practice include: aims of the National Policy on Culture and Heritage 920090; funding for AHM in country; involvement of local communities and other stakeholders in planning and management of Archaeological Heritage; presence of inventories; institutional framework; research component; documentation, storage and retrieval systems. Other areas include: involvement of the private sector in AHM; integration of heritage into development efforts; punitive measures; and community empowerment component in heritage management.

2.4.2. The National Policy on Culture and Heritage of 2009

- The policy was drafted by the Ministry of State for National Heritage and Culture under the Office of the Vice-President. The government recognizes the importance of national heritage and culture to sustainable socio-economic development of the country. The policy indicate that culture takes diverse forms across time and space and the diversity is embodied in the uniqueness and plurality of the identities groups and societies constituting humanity. The government recognizes the role of culture in sustainable development and the achievement of a more satisfying moral, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual existence. In its policy statements, GOK commits itself to take all necessary steps to ensure the protection and promotion of culture and of cultural diversity among Kenyans. It also commits to taking all necessary steps to ensure the protection and promotion of the country’s national heritage. Policy that takes the challenges posed by free trade, modernization and democracy into account while at the same time reflecting on good governance. There is also need for a policy that balances the need for respecting cultural diversity, with that for sustainable development and respect for human right.

2.5. Planning and Management Strategies for Policy Implementation

- Planning is a widely accepted method for handling complex problems of management and decision making. It involves the use of collective intelligence and foresight to chart direction, order harmony and make progress in public activity relating to human environment and general welfare (Owino, Hayombe & Agong’, 2014; Mahesh, Nitim & Vivek, 2012). Dunga required the following planning proposals to make it more comfortable for residents and visitors are: road (tarmac road) upgrading, construction of accommodation facilities, supply of clean water, sanitation improvement, and health center while some general ones are; cultural dance, training /learning tourist institution, improved social amenities facilities and improved government policies i.e. affordable business lances’ and entry fees. There were no police officers at the beaches while there were emergency specialists within Dunga. Focus group discussion outlined that the visitors did not feel safe walking and travelling alone within Miyandhe and some parts of Dunga. This could be addressed through: having frequent police patrol and tour guides and village elders.Abindu site needs several cultural strategies for cultural planning and heritage site management. The strategies include: Capacity building of the local people on cultural heritage due to the low level of domestic tourists coming to the site; There is need for provision of electricity in the area to light up the site for camping purposes and picnics; Construction of cottages to be used by visitors to rest and replenish themselves during their visits to the site after a long journey on the hot tropical environment of the Lake Victoria Basin; Employment of the locals as site guards, tour guides and site managers to assist in the management, conservation and branding of the site; Educate and upscale the local community management committee for the local people to oversee the management, conservation and the daily operations of the site; Involve the local community in ecotourism eco-ventures such as the construction of curio shops for sale of local craft and art; Darajambili road through Ulalo–Wachara road should be improved to motorable standards or all weather road to increase access to the site; The community needs the development of Luo Gallery (Luo Kit gi Timbe) as depository for cultural artifacts and exhibition of the narrative documentation of the mythology; The community proposed the construction of a water pond (Yao) under the auspices of UNESCO to address the water scarcity for both human and livestock in the area; The community has requested construction of a Library to enhance reading culture in the neighborhood. What strategies are enumerated? Differentiate strategies, planning interventions and activities?At Kit-Mikayi, the following strategies were considered necessary for its cultural planning and management. Kit-Mikayi residents need heritage awareness creation on the value of the site to control human encroachment and site destruction through farming and human settlement. Careful and controlled use of the site by the religious groups that frequent the site should be enforced to check littering and dumping of waste at the site during burnt offerings used during prayer sessions. The site should have waste bins for collection of waste and any other refuse. The space for the visitors should be expanded by acquiring more land around the site and control of the flow of visitors into the site should be carefully managed to avoid mass visitor destruction of the cultural heritage site. Capacity building and training of the locals in heritage management especially among the CBO members is critical for proper heritage management. Documentation of the legends and mythology about the site will provide a permanent documentary record of its history for future generations. Construction of cultural information centre for storage and learning purposes as well as exhibition space for ethnographic artifacts from the local community for product diversification purposes. At Seme-Kaila, capacity building and awareness creation of the local community on the values of Seme-Kaila needs to be undertaken using heritage experts in association with the elders of the community so that the locals understand their relationship with the site to appreciate its cultural significance. This will enhance their participation in the management and conservation of the site. It is possible to work with the community and network with other stakeholders, while creating a sense of ownership among the community members. They can be involved at the planning and implementation stages of particular projects. Train the members around the site on basic hospitality management, governance, project management and entrepreneurial skills to assist them in the management of the site. The protection and recognition of Seme-Kaila as a cultural heritage site should be a major priority in conservation and development plans. Such recognition and protection will enhance the usefulness of the heritage and make it more attractive. A conservation monitoring centre with facilities for data collection and analysis, photography and other documentation equipment, storage among others, will require more personnel, especially, experts in these fields who will assess any threats and plan for remedial actions to be taken. To have effective management and conservation of the site and its environs, there is need to build a cohesive human resource for a community driven management committee structure, characterized by a clear and efficient hierarchy in which to carry out continuous conservation, management and development agenda. A local community management structure needs to be put in place. Occupants of the offices should be competitively selected or appointed so as to realize desired results. A building for the management of activities should be set up. Such an establishment will require relevant standby staff, such as, office support staff to help senior officers in the management process. More research activities should be carried out at the site to consolidate information on cultural identity that will make the heritage more interesting and enjoyable to both the local community and tourists. Such research will bring out the values of the heritage leading to more attention from relevant government departments and even donor agencies. The results of such research work will form part of the information flow needed at the site in the form of publications, brochures, information panels and boards. Information from research will help in marketing and enhancing educational programs that may be run at the heritage. Such information may be used in other publicity campaigns, such as, in workshops and seminars, public meetings, radio programs, video shows, advertisements, folk media like festivals, drama and dances. To make the heritage more useful and economically relevant, there will be need to get the support of all stakeholders in marketing and image creation of the site. Marketing should be done by opening up and developing a trail network, as well as, setting up site signage leading to the various enclosures and objects within Seme-Kaila. Long term plans should include putting in place visitor facilities such as interpretation centre, community centre (shops, restaurants) and picnic areas among others. It will be necessary to construct rest places and toilets at tourist attraction areas within the site.

3. Conclusions and Recommendations

- At Dunga, some of the identified future cultural planning strategies for future site management and development were: improvement on road infrastructure; social services facilities to construct; improvement of information center; standard tour boats and rescue boats; improvement on health facilities; trained divers; and improvement of the beach. The other forms of activities that would benefit the local residents more than tourism are: standard boats and hotels to be managed by Beach Management Units (BMU) and community. There is need to establish collaborations with stakeholders in other tourist’s destinations such as Abindu, Kit-Mikayi, Luanda Magere, Ruma National Park, Tom Mboya Mausoleum and Thimlich Ohinga through networking and sharing of ideas.Abindu requires the following strategies for cultural planning and heritage management: Capacity building, provision of electricity, construction of cottages for accommodation, conservation and branding, employment of trained locals as site guards, tour guides and site managers, accessibility improvement by upgrading of roads, development of Luo Gallery (Luo Kit gi Timbe) for cultural artifacts and narrative exhibition, adequate provision of safe water and proper financial and management structure.Kit-Mikayi needs the following planning strategies for cultural planning and good management of the site: heritage awareness creation, community involvement in planning and management of the site, careful and controlled use of the site, proper waste management (waste bins), acquiring more land around the site for recreational activities, capacity building and training of the locals, documentation and recording of site history, and construction of cultural information centre.Seme-Kaila needs creation of networks with other stakeholders and sites, architectural reconstruction, restoration of the stone walled enclosure settlements, development of site infrastructural facilities, marketing and branding as well as site signages at the site. In summary, in order to make cultural heritage promotion and planning in Kisumu sustainable and more appealing to domestic and international tourists, some strategies need to be adopted. These include collaboration among stakeholders, the promotion of attractive cultural heritage tourism products and the conservation of county cultural and historic resources. Due to its very nature, cultural heritage planning for sustainable growth requires effective partnerships. Therefore, there is need for local communities, NGOs, Kenya’s government, county government and development partners to work closely together in order to develop robust and sustainable cultural heritage promotion that can make a community a better place to live as well as an attractive cultural place destination. Co-production initiatives for social inclusivity of all stakeholders in the planning, management and conservation of these cultural heritage sites should be addressed through partnerships, networks or collaboration between the academia as the intermediary, policy makers (county and national officials), private practitioners, and industry players as well as the international community. A deliberate effort should be made by all stakeholders to make tourist experiences as exciting, engaging and interactive as possible. This is particularly so given that today’s cultural heritage tourist is more sophisticated and expects a high level of quality and an authentic experience. Many of Kisumu county’s cultural heritage resources are irreplaceable. There is an urgent need to take good care of them for once they are lost, we will never get them back.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors of this report wish to thank all the respondents from the three cultural heritage sites, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST), Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP) secretariat for their various support, which contributed to the success of this study. We further appreciate the support from Mistra- Urban Futures (M-UF)/Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) that has enabled cultural heritage to become an important component of urban sustainability initiative in Kisumu city. Their active support and discussion contributed greatly to the success of the study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML