-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2019; 5(2): 31-35

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20190502.03

Neuroticism as Predictor of Suicidal Behavior among Secondary School Students in Kenya

John Agwaya Aomo

Ministry of Education, Kisii County Office, Kisii, Kenya

Correspondence to: John Agwaya Aomo, Ministry of Education, Kisii County Office, Kisii, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The present study investigated the relationship between Neuroticism and suicidal behavior among secondary school students in Kenya. The Correlation survey design was adopted for the study. The sample of this study consisted of 120 secondary school students within Kitutu Central Sub-County, Kisii County, Kenya. The study used Aaron Beck suicidal inventory and Neuroticism Scale Big Five Factor for Personality inventory. A reliability coefficient of 0.743 was reported. Quantitative data collected from questionnaires was analyzed using linear regression analysis. The results indicated that there was a significant relationship between neurotic and suicidal behavior (R = .587; p<.0.05). Regression analysis was used to test if neurotic personality significantly predicted suicidal behavior among students. The results of the regression indicated that neurotic personality explained 34.5% of the variance in suicidal behavior (R2 =.345, F (1, 68) = 45.167, p<.05). It also found that neurotic predicted suicidal behavior (B = .326, p<.05). It’s recommended that the teacher counselors should regularly perform personality assessment to identify neurotics who are at risk of suicidal attempts.

Keywords: Neuroticism big five factor personality, Suicidal behavior, Secondary school, Students, Kenya

Cite this paper: John Agwaya Aomo, Neuroticism as Predictor of Suicidal Behavior among Secondary School Students in Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2019, pp. 31-35. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20190502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 800,000 people die by suicide every year, with one person dying every 40 seconds. It is the second leading cause of death among 15 to 29-year-olds; most of whom are adolescents (Suicide, 2015). Reports of suicide have been increasing in the Philippines and have become an alarming issue in the country. In a study conducted by Redaniel, Lebanan- Dalida, & Gunnel (2011), the incidence of suicide had increased in the Philippines for both males and females between 1984 and 2005. Suicide rates went from 0.23 to 3.59 per 100,000 males, and from 0.12 to 1.09 per 100,000 females between 1984 and 2005. Suicide and suicide behavior are issues that the Philippine government and various organizations are seeking to address, so much so that numerous prevention programs have been established. Senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago introduced Senate Bill No. 1946, the “Student Suicide Prevention Act of 2005”, which mandates that school organizations such as the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) and the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) provide proper programs to reduce suicide attempts and completed suicides. As defined by Pompili (2010), suicidology is the study of suicide and suicide prevention. In suicidology, many interacting factors are associated with suicide but there is no single factor is causally sufficient, thus making suicide a complex concept (Pompili, 2010). Epidemiologists study suicide through associated risk factors, which are used to predict the likelihood of suicide behavior. Past research has identified demographic, psychiatric, psychological, biological, and stressful life events as the strongest major risk factors in predicting suicide behavior (Nock et al., 2008). Other risk factors associated with suicide behaviors include family disturbances, mental health problems, and previous suicide attempts (Scanlan & Purcell, 2009). Such risk factors may be considered “distal causes,” in that they influence the development of the specific emotions and cognitions that precipitate suicide behavior, but cannot be considered the direct cause of a suicide attempt. Hopelessness and helplessness, both associated with depression, are considered to be among the strong predictors of suicide behavior (Hewitt, Caelian, Chen, Flett, 2014). These may be considered “proximal causes,” in that they saturate the conscious awareness of the desperate person, thereby preceding and producing suicide behavior and suicide attempts. Factors that help decrease a person’s probability of attempting suicide are called protective factors. Research studies have found religiosity to be one of the strongest among them. Moral objections and social support also seem to protect people against suicide attempts (Nock et al., 2008). Interest between the relationship of personality traits and suicide behavior has been increasing for the past few years (Brezo, Paris, & Turcki, 2005). According to Brezo, Paris, & Turecki (2005), personality traits are linked to suicide behavior because traits contribute to a diathesis for suicide behavior. In the diathesis model, pathological behavior is seen as the product of internal characteristics and external events. Internal characteristics constitute a vulnerability that can, in conjunction with precipitating external events, create a window of opportunity for the emergence of pathological behavior. Personality traits reflect a propensity or disposition toward those cognitions, emotions, and behaviors which are consistent with the trait. Since situations are also important, traits do not determine behavior, but instead influence its baseline probability. The connection between personality traits and any actual, concrete behavior is therefore indirect and probabilistic. Personality traits are determined by genes, environment, and the interaction between genes and environment (Brezo, Paris, & Turecki, 2005). There has been exponential growth in research examining the prevalence, correlates and aetiology of suicidal behaviours in young people (Gould & Kramer, 2001). This research has established that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are rela- tively common among young people and that risks of these behaviours are best explained by an accumulative risk model in which social dis- advantage, childhood adversity, mental health problems, personality factors and exposure to stress combine to influence risk. A report by Woodward (2005) revealed that, in India one third of suicide cases were mainly young people, Youth suicide in this case is when a young person generally categorized as someone below age 21 deliberately ends their own life (Machi, 2017). The rates of attempted and completed youth suicide in Western societies and other countries are high. The research reports also indicates gender differences in both males and females however, suicidal thoughts are common among girls, while adolescent males are the ones who usually carry out suicides (WHO, 2007). On a similar note, studies from Kenya also reports greater elements of suicidal behaviours among the youths. The study conducted by Khasakhala, Maithai and Ndetei (2013) on suicidal behaviuor associated with psychopathology in both parents and youths showed there was a significant relationship between maternal depressive disorders (p<0.001) and perceived Maternal rejecting parental behaviour (p<0.001)with suicidal behaviour in youths. The study further reported that a higher proportion of youths between 16-18 years hd suicidal behaviour than the youths below 16years or above 18 years 0f age (p = 0.004). According to Muiru, Thinguri and Macharia 2014) showed that family history had a significant contribution to youth and adults suicidal ideation and attempts in Kenya. Ongwae (2015) revealed that the most common methods of suicide were: use of poison, landlessness, land disputes, domestic conflicts alcoholism, irresponsible families, family violence and terminal illness. Njagi, Mwania, Manyasi and Mwaura (2017) study showed that parenting styles have a positive and a significant prediction for the risky sexual behaviours among the secondary school students and that parenting styles account for 57.2% (R2 = 0.572, P < 0.05) of secondary school students risky sexual behaviour. Blum, Kaputsa, Doering, Brahler, Wagner and Kersting (2013) assessed the impact of the Big five personality dimensions on suicide in a representative population based sample of adults. The study employed interviews on a representative German population based sample (n=2555) in 2011. The study result showed that Neuroticism and openness were significantly associated with suicide risk. Cameron, Brown, Dritschel, Power and Cook (2017) aimed to conducting within- and between-group comparisons of known suicide risk factors that are associated with emotion regulation (neuroticism, trait aggression, brooding, impulsivity, and over general autobiographical memories). Correlation design using between- and within-group comparisons from self-report measures Inter- and intergroup differences were identified using Pearson's correlation coefficients and tests of difference. An analysis of indirect effects was used to investigate whether the relationship between suicidality and current low mood was mediated by neuroticism, trait aggression, brooding, impulsivity, and over general autobiographical memories, and if this relationship varied according to group types. The relationship between suicide attempts and current low mood showed greater associations with brooding, trait aggression, and over general autobiographical memories.The study was informed by the Lewis Goldberg proposed the Big five factor for personality and developed international personality item pool (IPIP) on inventory of descriptive statements relating to each trait. The big five factor model included the openness to experience a dimension of personality which is characterized by a Willingness to try new activities and that people with higher openness are amenable to unconventional ideas and beliefs; including those which challenge their existing assumptions, however people with low levels of openness are closed to experience, are wary of uncertainty and the unknown, they are more suspicious of beliefs an d ideas which challenge their status quo, they feel uncomfortable, in familiar situations and proper familiar environment. However, less open individuals value the safety of predictability and like to adhere to well known traditions and routines.Blulml et al (2013) study assessed the impact of the Big Five personality dimensions on suicidality in a representative population based sample of adults. The finding reported that neuroticism was significantly associated with suicide risk. Neuroticism was found to be associated with suicide risk only in females. These associations remained significant after adjusting for covariates. Duberstein et al (2010) assessed the relationship between personality traits and suicidal behaviours in depressed inpatients 50 years of age and older. Results were generally consistent with the hypotheses. It was reported that there was a relationship between neorotiscm and suicidal ideation. These findings suggest that longstanding patterns of behaving, thinking, and feeling contribute to suicidal behavior and thoughts in older adults and highlight the need to consider personality traits in crafting and targeting prevention strategies. Bo et al (2017) administered self-reported tests and clinical interviews to 196 people who have attempted suicide who were admitted to a hospital emergency room or our psychiatric settings after a suicide attempt. One hundred and fifty-six subjects (79.6%) met the criteria for Axis I disorders and eleven (6.6%) met the criteria Axis II personality disorders. Those who have attempted suicide who did not have psychiatric disorders exhibited less neuroticism. Mohamed et al (2014) aimed to assess some demographic profile and personality traits in relation to suicidal ideation in depressive disorders In Egypt. there was a statistically significant relation between suicidal ideation and Psychoticism and Neuroticism personality domains. Peters et al (2018) examined whether neuroticism is associated with suicide deaths after adjusting for known risks in UK. The findings reported that neuroticism increased the risk of suicide in both men (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.22) and women (HR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.27). In subsamples that were assessed for mood disorders, neuroticism remained a significant predictor for women (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03–1.51) but not for men. Walker et al (2017) studied the relationship between Neuroticism and suicidal behavior among a sample of 223 low-income, primary care patients. There was a significant indirect effect of neuroticism on suicidal behavior through hopelessness, and this indirect effect was moderated by social problem solving ability. Patients with greater neuroticism also manifest greater levels of hopelessness and, in turn, more suicidal behavior, and these relations are strengthened at lower levels of social problem solving. Most of the studies on suicidal behaviors in Kenya had focused on causes, family histories, conflicts, psychopathology, and sexual risky behaviours and parenting styles whereas, the current study explored the relationship between personality subtypes and indulgence in suicidal behaviour among secondary school students in Kitutu Central Sub-County, Kenya.The hypothesis was stated as follows: Neuroticism as a predictor of suicidal behavior among secondary school students in Kenya.

2. Research Methodology

- The ex-post facto research design was adopted in the present study. Target population was 6284 secondary school students drawn from Kitutu Central, Kisii County, Kenya. A Sample size was 120 students drawn from boys and girls boarding, and mixed secondary schools in the ratio of 60% (72) and girls 40% (48) this was due to the fact that both girls were involved in suicidal behaviuors. The students were in the age bracket of 14-18 years and were selected using stratified random sampling technique. The study used Aaron Beck Suicidal Inventory and Neurotic Scale from big five Factor for Personality inventory to collect data. A reliability coefficient of 0.743 was reported. For data collection, 8 item 5 point Likert Scale was designed to measure neurotic personality and another 10 item 5 Likert scale for suicidal behavior was designed the responses were positively coded on a scale0f 1to 5 where 1= strongly disagree 2= disagree 3= neutral 4= agree 5=strongly agree. Consequently, to obtain continuous data for regression from the ordinal likert scale data, summated scores on each of the scales was obtained for each respondent. In total, there were 70 complete responses used in the analysis. Permission to conduct a study was obtained from Ministry of Education- Kisii County. The data was analyzed through simple linear regression with the aid of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. The findings were presented using frequencies, tables, standard deviations, mean differences and percentages.

3. Results & Discussions

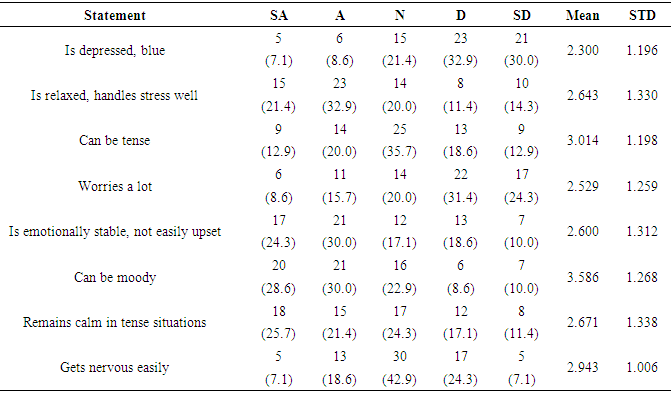

- To assess the Neuroticism, students were asked to given their opinion on the following statements related to neuroticism. The respondents were given 5- point likert scale statements as strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree as indicated in Table 1 below:

|

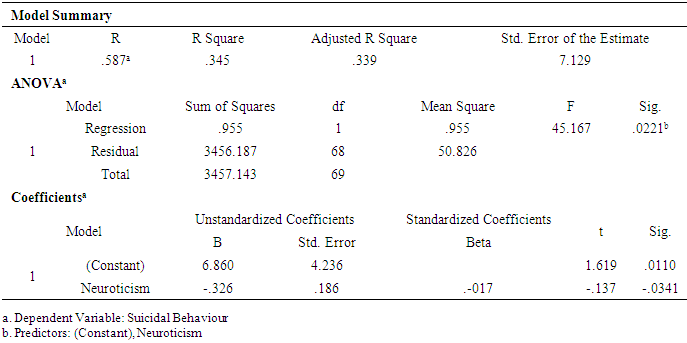

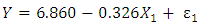

Where Y is suicidal behavior, B0 is the coefficient of the constant term relating suicidal behavior and neuroticism, B1 is coefficient of neurotic personality, X1 is neurotic personality and

Where Y is suicidal behavior, B0 is the coefficient of the constant term relating suicidal behavior and neuroticism, B1 is coefficient of neurotic personality, X1 is neurotic personality and  is error term for the equation.

is error term for the equation.

|

This shows that enhanced neurotic personality within leads to increased chances of committing suicide. This finding agreed with Peters et al (2018) who examined whether neuroticism is associated with suicide deaths after adjusting for known risks in UK. The findings reported that neuroticism increased the risk of suicide in both men (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.22) and women (HR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.27). In subsamples that were assessed for mood disorders, neuroticism remained a significant predictor for women (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03–1.51) but not for men. Walker et al (2017) reported that there was a significant indirect effect of neuroticism on suicidal behavior through hopelessness, and this indirect effect was moderated by social problem solving ability. Patients with greater neuroticism also manifest greater levels of hopelessness and, in turn, more suicidal behavior, and these relations are strengthened at lower levels of social problem solving.

This shows that enhanced neurotic personality within leads to increased chances of committing suicide. This finding agreed with Peters et al (2018) who examined whether neuroticism is associated with suicide deaths after adjusting for known risks in UK. The findings reported that neuroticism increased the risk of suicide in both men (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.22) and women (HR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.27). In subsamples that were assessed for mood disorders, neuroticism remained a significant predictor for women (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03–1.51) but not for men. Walker et al (2017) reported that there was a significant indirect effect of neuroticism on suicidal behavior through hopelessness, and this indirect effect was moderated by social problem solving ability. Patients with greater neuroticism also manifest greater levels of hopelessness and, in turn, more suicidal behavior, and these relations are strengthened at lower levels of social problem solving. 4. Conclusions & Recommendations

- It’s concluded that neuroticism as a predictor to suicidal behavior. Regression analysis was used to test if neuroticism significantly predicted suicidal behavior among students. The results of the regression indicated that neuroticism explained 34.5% of the variance in suicidal behavior. It also found that neuroticism predicted suicidal behavior. It’s recommended that the students’ counselors should regularly perform personality assessment to identify neurotics who are at risk of suicidal attempts.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML