-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2019; 5(1): 7-14

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20190501.02

Relationship between Goal-Setting and Mathematics Achievement among Students in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya

Charles Onchiri Ong’uti1, Peter J. O. Aloka2, Joseph Otula Nyakinda3

1PhD Student in Educational Psychology, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2Department of Psychology and Educational Foundation, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

3School of Mathematics & Actuarial Sciences, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter J. O. Aloka, Department of Psychology and Educational Foundation, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study was to investigate selected goal-setting as a predictor of mathematics performance among students in public secondary schools in Kisii Central Sub-County, Kenya. The study was guided by the Social Development Theory (1978) by Levi Vygotsky and the Theory of Education Productivity by Walberg (1981). The study employed the Solomon Four pretest-posttest two group design with posttest only control design. The study population included 1665 form 3 students and 41 form 3 mathematics teachers from public secondary schools in Kisii Central Sub County, Kenya. Purposive, stratified and simple random sampling technique was used to select the participants. The sample size comprised of 360 form 3 students and 11 form 3 mathematics teachers. Questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data while qualitative data were collected using interview schedules. The normality of goal-setting was established using the Shapiro-Wilk test and was established at Lilliefors significance Correlation of value .961. Trustworthiness of qualitative data was ensured using Shenton (2004) criteria for trustworthiness. The study used descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze quantitative data while qualitative data were analyzed with the help of the thematic framework. The findings revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between goal-setting and mathematics achievement. The study further established that students who set goals performed better in mathematics than their counterparts who did not set goals. The study recommended that universities, which train secondary school teachers, should include aspects of goal-setting as a self-regulated learning technique in their training programmes.

Keywords: Goal-setting, Mathematics performance, Students, Public, Secondary schools, Kenya

Cite this paper: Charles Onchiri Ong’uti, Peter J. O. Aloka, Joseph Otula Nyakinda, Relationship between Goal-Setting and Mathematics Achievement among Students in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2019, pp. 7-14. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20190501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

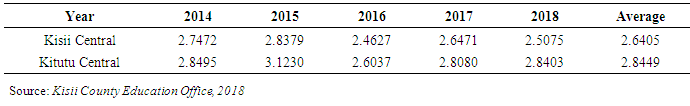

- Education has been used as a tool for preparing children to acquire work skills that can place themselves in competitive job positions in their countries as well as in the increasingly competitive global markets (Uchechi, 2013; Olugunju, 2015). This performance based environment places children under pressure from their parents and teachers to outperform each other in national examinations (Anderman and Wolters, 2006; Mutua, 2014). A changing and economically competitive world has necessitated reform in mathematics education which has been given a lot of prominence in school systems in many nations across the globe as it is regarded as a “thinking” subject by which students are able to make observations, reflect and reason logically about learning challenges (Iji, 2008). However, performance outcomes indicate that many students encounter learning difficulties in their academic lives prompting educational psychologists and guidance counselors to turn their attention in trying to understand key processes through which learners may Self-Regulate (SR) their academic tasks and experience improved performance outcomes (Furner and Gonzalez-DeHass, 2011). Global studies have shown that academic achievement can be influenced positively by self-regulating certain personal factors of learners such as goal setting and attribution among others (Delucchi, 2007; Zimmerman, 2008). Self-regulation enables learners to independently plan and manage their thoughts, emotions and behaviours within a learning environment to successfully direct their learning outcomes (Zimmerman, 2008; Jarvela and Jarvenoja, 2011; Zumbrum, Tadlock and Roberts, 2012).Numerous studies in the developed west have shown that goal-setting is a positive predictor of mathematics achievement. For example, Mok, Wong, Su, Tognolini, and Stanley (2014) conducted a study to identify how personal best goals and self-regulation predicted mathematics achievement among primary 3 to 5 students in Hong Kong. The results of the study indicated that students’ personal best goals predicted mathematics performance at all levels. Rowe, Mazzotti, Ingram and Lee (2017) investigated the effects of goal-setting instruction on academic engagement for middle school students at risk of academic failure in the United States and concluded that when goal-setting was employed in mathematics, the learners became actively engaged and attained improved outcomes. In Saud Arabia, Alotaibi, Tohmaz and Jabak (2017) established a statistically significant relationship between self-regulation and achievement in mathematics. Similar findings were arrived at by Martin and Elliot (2016) in a study among elementary and secondary school students in mathematics in Australia, and Smithson (2012) in a study among elementary school children in Georgia, USA arrived at similar results. In New Zealand, the inclusion of a self-regulation component in the school curriculum led to improved performance among secondary school students (Ministry of Education, 2007).In Malaysia, examination outcomes have shown that students in secondary schools continue to perform poorly in mathematics in spite of the many strategies that have been put in place to improve its performance (Ismail, 2008), and yet Loong (2012) demonstrated that self-regulated learning techniques were used to improve performance in mathematics among international university students in Malaysia. Although Ignacio and Reyes (2017) found that there was no significant difference in the mathematics achievement goals based on learning styles among students in the Philippines, there was an overwhelming observation that the majority of studies concluded that goal-setting was significantly positively correlated with mathematics achievement. For instance, Riyaz (2013) did a study to determine if higher secondary students’ beliefs about their mathematical ability, goals, and learning strategies were related to their mathematics achievement. The study findings indicated that mastery goals and deep learning strategies were significantly related to mathematics achievement.In Nigeria, Iyabo, Chibuzoh and Louisa (2014) carried out a study which established that goal-setting skills improved academic performance in English among students in secondary schools, while Aloysius and Onyadike (2012) established a significant correlation between goal-setting and mathematics achievement among students in secondary schools. Musa, Dauda and Umar (2016) found out that goal-setting significantly improved performance in mathematics boarding secondary school students.In Kenya, Mutua (2014) investigated students’ academic motivation and self-regulated learning as predictors of academic achievement. The results revealed that intrinsic motivation towards accomplishment and organizing strategy had the highest positive predictive value on academic achievement. Students’ self-regulated learning was found to have the highest positive predictive value on academic achievement as compared to academic motivation.The literature review in the present study covered investigations on the relationship between goal-setting and mathematics achievement from the Western world, Asia, Europe, Africa, as well as local Kenyan research findings. The review which also examined the relationship between goal-setting and mathematics achievement among students in public secondary schools in Kisii Central Sub County, Kenya found few studies on goal-setting variable as a predictor of mathematics achievement. The reviewed literature strongly supported the proposition that goal-setting correlated significantly and positively with mathematics achievement, and that learners who set goals were able to use goal-setting technique to realize better academic outcomes (Gibbs and Poskitt, 2010). None-the-less, the reviewed literature identified some gaps which formed the basis for the present study.Walberg (1981) posits that self-regulated learning techniques improve mathematics achievement among learners. Studies from developed countries (Bernard, 2013; Froiland and Davison, 2016; Long, 2012; Mutua, 2014) demonstrated that self-regulated learning techniques improve mathematics performance. However, Bakare (2015) observes that comparatively fewer studies have been undertaken to investigate what Self-Regulated Learning techniques can do to improve performance outcomes, yet this ability and willingness to implement, monitor, and evaluate various self-regulation learning techniques has increasingly been found to improve mathematics achievement among students across different levels of learning globally.Most of the studies which have been carried out have tended to investigate the student variables such as socio-cultural background, gender, attitudes, self-efficacy and motivation level, and their influence on academic achievement among secondary school students (Filmer, 2005; Lee, Zuze and Ross, 2005; Harri and Petteri, 2012; Filmer, Mutua, 2014). Teacher education researchers have extensively researched on curriculum and instruction while the constructs of self-regulated learning techniques have been left for educational psychologists who have observed a close relationship between self-regulation and its predictive properties on academic achievement (Wang, Wang and Li, 2007; Zimmerman, 2008). In Kenya, performance among students at the KCSE mathematics examinations has been poor for many years (Barmao, Changeiywo, and Githua, 2015). In Baringo County, Kenya the average mean score over a period of 10 years (1999-2008) was 16.013 (Mbugua, Komen, Muthaa and Nkonke, 2012).In Kisii County, results for KCSE mathematics analysis obtained from the Kisii County Director of Education for the years 2014 to 2018 showed that students in public secondary schools performed poorly. Table 1 presents the mean scores for two sub counties.Table 1 shows a declining trend in mathematics performance in Kisii Central Sub County from a mean standard score of 2.7472 in 2014 to a mean standard score of 2.5075 in 2018. In Kitutu Central Sub County, there was a decline in the mean standard score from 2.8495 in 2014 to 2.8403 in 2018. The average mean score in the same period for Kisii Central Sub County was 2.6405 and that of Kitutu Central Sub County was 2.8449. These MSS averages were lower than the national mean for 2015 which was at 3.4000.

|

2. Research Methodology

- The present study employed the Solomon Four research design which is a standard pretest-posttest two group designs with a posttest only control design, involving a comparison of four groups instead of two groups used in a quasi-experimental approach. The design was preferred because it allowed the researcher to use self-reporting questionnaires and interviews to capture participants’ views, knowledge, opinions and experiences concerning the study variables (Creswell, 2014; Bryman, 2012). Thus, the researcher was able to apply both quantitative and qualitative approaches of data collection and analysis to examine the relationship between goal-setting and performance in mathematics.The Solomon four design involved selectively administering an intervention programme to four groups (A, B, C, and D) randomly selected into the groups to investigate the effect of goal-setting intervention programme on performance in mathematics. The first two groups (A and B) were designed and interpreted in exactly the same way as in the pretest-posttest quasi-experiment design and, therefore, provide the same checks upon randomization. The second two groups (C and D) did not have a pretest, only a posttest. Further, Group ‘B’ and ‘D’ were control groups and therefore, they did not get the intervention, which was only administered to group ‘A’ and ‘C’. A series of comparison of the pretest and posttest results between and within the groups enabled the researcher to tell whether the pretests influenced the results. Significantly different results showed that pretesting influenced the overall results. Therefore, the pretest would require refinement.Solomon four design was appropriate to use in the present study because it was possible to control for extraneous factors in several ways. First, the respondents were assigned randomly into their groups through the admission process. Second, the respondents and researcher were masked so as to avoid biases cropping into the research. Third, the design utilized respondents who had similar characteristics. Fourth, its two extra control groups reduce the influence of confounding variables and enables the researcher to test whether the pretest itself had an effect on the subjects. Fifth, the researcher was able to examine between-group differences.The study targeted 30 public secondary schools, 1665 form 3 students and 41 form 3 mathematics teachers and obtained a sample size of 4 schools, 360 students, and 11 form 3 mathematics teachers using purposive, stratified, and simple random sampling techniques (WHO, 2009; Creswell, 2014). Goal-setting questionnaire for students was used to collect quantitative data while qualitative data from students was collected using focus group discussions. The study also employed a one-on-one interview schedules to obtain qualitative data from form 3 mathematics teachers. To ensure validity of research instruments in the present study, face, construct and content validities of questionnaires, and interview schedules was determined through discussion with two experts from the School of Education in Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST) who gave their views on the relevance, clarity and the applicability of the questionnaire and interview schedule. Their suggestions were in cooperated in the final instruments which were used to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. Reliability of the goal-setting questionnaire was computed using Cronbach’s alpha and found that all the items had good internal consistency, α = .751; all the items of this subscale were worthy of retention. Oso and Onen (2013) posit that instruments with an internal consistency of alpha greater than .70 is adequate for data collection in a study. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze quantitative data while qualitative data were analyzed thematically.

3. Findings and Discussion

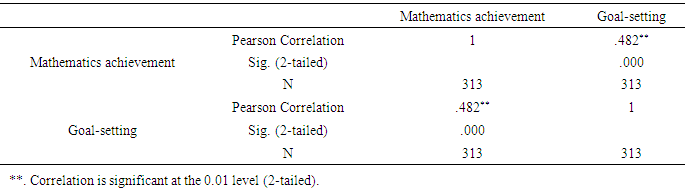

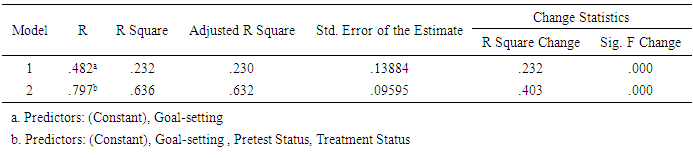

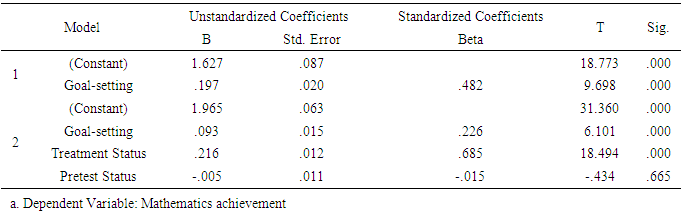

- To establish whether there was any statistical relationship between goal-setting and mathematics achievement the null hypothesis was tested. The hypothesis stated:H0: There is no statistically significant relationship between goal-setting techniques and mathematics achievement among students in public secondary schools in Kisii Central Sub County, Kenya.To establish how goal-setting predicted mathematics achievement among students in public secondary schools, a Pearson Moment Correlation Coefficient was used to investigate the influence. Table 2 presents the correlation analysis results of SPSS output.

|

|

|

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The overall objective of the study was to investigate the influence of intervention through trainings on goal-setting technique as predictor of mathematics achievement among students in public secondary schools. The results showed that groups that received treatment reported statistically significant positive mathematics achievement than their counter parts who did not receive treatment. Hence, the study concluded that the use of goal-setting learning technique was effective in improving performance in mathematics among students in public secondary schools. Following findings that goal-setting is a significant predictor of mathematics performance among students in public secondary schools, the study recommends that the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development infuse a component of goal-setting in the secondary school curriculum. The study further recommended that teacher counselors be trained to identify students with weak goal-setting skills so that they could be assisted to perform better in mathematics. This study contributed significantly to the body of literature on goal-setting as a predictor of mathematics performance. However, since there were few local studies observed during literature review, the study recommends that future investigations could focus on group dynamics as a predictor of academic achievement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML