-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2018; 4(2): 32-38

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20180402.02

Parental Responsiveness as a Predictor of Behavioural Adjustment among Primary School Pupils in Kisii Central Sub-County, Kenya

Evans Apoko Monda, Peter Jairo Aloka, Benard Mwebi

Psychology & Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, Kenya

Correspondence to: Evans Apoko Monda, Psychology & Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

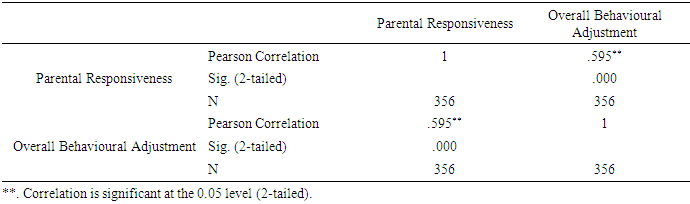

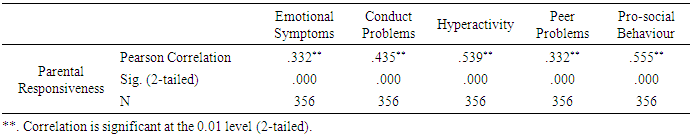

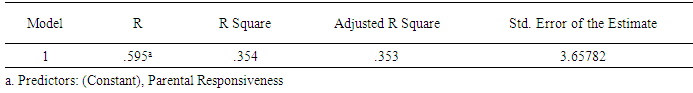

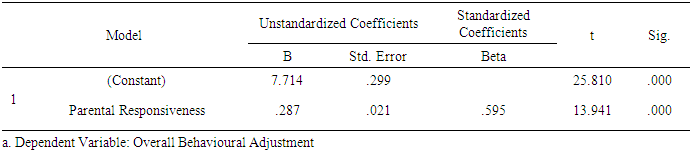

The present study sought to investigate the relationship between parental responsiveness and behavioural adjustment among pupils in primary schools in Kisii central Sub-County, Kenya. The study was guided by the Object relations theory and supported attachment theory. The study adopted mixed method approach in which the embedded research design was used. To obtain the sample for the study, the study used cluster sampling, stratified sampling and simple random sampling techniques. The unit of analysis included 218 primary schools. The target population comprised of 14876 pupils, 10582 parents, 229 deputy head teachers and 218 guidance and counselling teachers. The sample size for the study consisted of 374 pupils, 30 parents, 30 deputy head teachers and 30 guidance and counselling teachers. The study also employed questionnaires and interview schedules to gather data. The study adopted the triangulation approach to measure the validity of the instruments. Split half method was also used to establish the reliability of instruments whereby the correlation coefficient value of .808 was established. In analysing qualitative data, the study used thematic analysis while descriptive and inferential statistical techniques were used to analyse quantitative data. The study established that there was statistically significant positive (r=.595, n=356, p<.05) relationship between parental responsiveness and pupils’ overall behavioural adjustment and all the five aspects of behavioural adjustment (conduct problems, peer relationship problems, emotional symptom, hyperactivity and pro-social behaviours). The study further established that parental responsiveness alone accounted for 35.4% of the variation in the overall behavioural adjustment among the pupils of class 7 and 8, as signified by coefficient R2 of .354. On the same note, if the parental responsiveness increases by one unit then level of overall behaviour adjustment would improve by .287 units; this is a considerable effect from one independent variable. The results further indicated that most of the children’s problematic behaviour outcomes were as a result of parents frequently ignoring children’s needs. The study also established a link between perceived parental emotional support, trustworthiness, understanding, physical support and sensitivity to children’s needs and children’s positive behavioural reputations, competencies and self-perceptions.

Keywords: Parental responsiveness, Behavioural adjustment, Primary school pupils, Kenya

Cite this paper: Evans Apoko Monda, Peter Jairo Aloka, Benard Mwebi, Parental Responsiveness as a Predictor of Behavioural Adjustment among Primary School Pupils in Kisii Central Sub-County, Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2018, pp. 32-38. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20180402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Students’ indulgence in behaviour problems has been a threat to the serenity and peacefulness enjoyed by members of the families, schools and community in the last two decades (Augustine, 2012). Beside the gradual moral degeneration which befalls the society where pre-adolescent and adolescents involve in behaviour problems, there arises security and economic cost to a nation fraught with juvenile deviant behaviours due to students’ lack of necessary behaviour adjustment strategies (Simoes, Matos & Batista-Foguet, 2008). Hence, students’ maladjustment has become one of the global social issues which many developed and developing countries are currently trying to manage and bring under control amidst the glaring evidence that, if the right nurturance is not given to young children, pre-adolescents and adolescents, they graduate as adult without social and emotional competencies (Hess & Drowns, 2010).However, studies have also shown that every human being is born a creature dependent upon parental nurturance (Chien, Harbin, Goldhagen, Lippman & Walker, 2012). It is also believed that during one's life there is a battle between the need to be nurtured and the desire to be independent (Guzman, Caal, Ramos & Hickman, 2014). Due to these two conflicting forces, many young boys and girls are faced with the task of redefining themselves in terms of psychological adjustment and developing appropriate psychosocial behaviours. Over the last two decade however, a series of studies have constantly found that parents have a crucial role of preparing their children for adulthood through nurturing and moulding appropriate behaviours (Gavazzi, 2006). This suggests that the family rearing environments and practices compose a fundamental ecology where the young children’s behaviours are usually nurtured, manifested, acquired, encouraged and moulded (Dishion and Patterson, 2006). In spite of this new sphere of influence, others studies have also observed that parenting rearing practices accounts in many instances for great variance and inconsistence in externalizing and internalizing behaviours among school going children (Crosswhite & Kerpelman, 2009). Therefore, having a clear understanding and knowledge on the importance of maintaining appropriate parenting practices is inevitable in the current society where we are witnessing moral degeneration.Globally, experts from various disciplines have expressed a great concern in relation to the implications of behaviours exhibited by adolescent, pre-adolescent and young children in their homes and learning institutions (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Statistics on students’ indulgence in behaviour problems have a worrying trend globally.In order to address social and emotional malfunctioning among children and adolescents, in 2006, the USA government established a welfare system to curb behaviour problems among school going children (Hill, 2007). In addition, in 2014 the government offered School Climate Transformation Grant for those schools that were seeking to implement problem behaviour intervention programmes and increase access to mental health services for school going children (USDE, 2014). Despite these efforts, the Centre for Behavioural Health Statistics and Quality (2015) established that in 2014, 27.0 million people aged 12 and above had used a variety of illegal drugs in the past 30 days, which corresponds to 10.2% of the Americans; slightly more than 2.3 million teenagers aged 12 to 17 were users of illegal drugs, which represent 9.4 percent of young people and an approximate of 655,000 youths aged 12 to 17 were nonmedical abusers of psychotherapeutic drugs which corresponds to 2.6% of teenagers. This behavioural maladjustment trends in USA is an indication that the government’s effort to curb behaviour problems has not brought impressive results.In the present era where every day we step ahead to technological advancement, breaking up of families and rapidly changing socio cultural paradigm, cases of behaviour problems among children are also similarly steep and disrupting. In India, review of studies done in the area of child development reveal that the prevalence of behaviour problems in children is alarmingly high (Jyoti, Mitra & Prabhu, 2008). However, this study found that the vulnerability of the children tended to increase when effective parenting was not available. This study was deliberately planned to assess the prevalence of behavioural problems among school going children and associated factors and predictors that were effective in behaviour management. However, the study did not address the effects of various elements of parental nurturing practices on students’ behavioural adjustment which the present study sought to address.In Ghana, for many years there has been an upward surge of young children’s involvement in behaviour problems (Bosiakoh & Andoh, 2010). According to the Department of Social Welfare annual performance report, two hundred and seventy six juvenile criminal behaviour cases were handled in 2007. Further, the Ghana prison service yearly report in 2010 also observed that there was an average daily lock-up of one hundred and fifteen children offenders who should be learning in primary or secondary schools. The effort by the parents and teachers to curb the problem of child delinquency has not brought impressive results owing to the fact that the number of juvenile delinquent cases are increasing every day. This is supported by evidence showing that students frequently involved themselves in theft cases like stealing from other students, breaking into school offices and other staff common rooms (Samuel, Rejoice & Gabriel, 2015). However this study did not establish the factors surrounding behaviour problem.In Zimbabwe, Student involvement in various behaviour problems has been a source of worry to stakeholders in education (Regis & Tichaona, 2015). Although effective parental physical and psychological control is needed for children’s acquisition of appropriate behaviour patterns, and most schools and homes have set standards of moral conducts and rules to control their children, the phenomenon of disruptive behaviour persists in Zimbabwe (Madziyire, 2012). This is because the cases of students’ indulgence in behaviour problems in Zimbabwean schools ranges from minor cases like going to school late, absenteeism, harassment, bullying and stealing to major cases like rape, violent fights, assassination and drug abuse (Ncube, 2013).In Kenya, adolescents frequently indulge in various behaviour problems which are manifested in the form of rioting, sexual violence, fighting and bullying (Changalwa, Ndurumo, Barasa & Poipoi, 2012). In the slums of Nairobi, drug abuse and misuse is a common behaviour problem among primary and secondary school students where 65% of young boys and girls use cigarettes, 52 % marijuana, 14% glue and 11% petrol (APHRC, 2002). With a lot of concern, over 26% of school going children who live in slums of major towns in Kenya frequently indulge in behaviour problems like violent fights, bullying, theft, truancy, watching pornographic materials and coming home late (Wairimu, 2013).Despite the government’s effort to curb behaviour problems through designing preventive programmes in school like the introduction of guidance and counselling in primary and secondary schools, reports on indiscipline cases are worrying. For instance between 2000 and 2001, two hundred and eighty schools reported cases of student unrest in Kenya (Republic of Kenya, 2001). In Kisumu Municipality, Ouma, Simatwa and Serem (2013) found that between 2006 and 2010 public primary schools experienced 9870 cases of pupil indiscipline. The behaviour problems experienced in primary schools included; noise making which was rated 3.7%, failure to complete class and other duties assignment to 3.8%, absenteeism 4.0%, unpunctuality 4.0%, stealing 3.5%, and sneaking out of school 3.5%. In Kisii and Nyamira County, Kostelny, Wessells and Ondoro (2014) established that 26.9% of the children drop out of school yearly, 11.5% of school girls experience early pregnancy annually, 9.1% of school boys and girls use alcohol and other illegal drugs and 3.5% of the girls frequently involved themselves in prostitution.In order to address behaviour problems among adolescents and preadolescent in Kenya and other parts of the world, the past two decades have witnessed a resurgence of concern in recognizing the factors that leave school boys and girls at a high and elevated possibility for manifesting dysfunctional behaviours such as internalizing problems (withdrawal symptoms, nervousness, anxiety, worry, despair, hopelessness and despair) and externalizing problem behaviours (irritation, hyperactivity, anger, annoyance, hostility, hostility, delinquency). Based on the ecological-system model (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), the developmental frameworks that is perceived to encourage and destabilize children’s growth and development consist of a multifaceted systems of family, school and community. Given that the family system is perceived as the main and principal context in which human development occurs, no one would doubt the crucial role parenting plays in the system (Newland and Crnic, 2011). Despite this established link, the mechanisms through which parents actually nurture their children’s behaviour remain unclear. Building on the existing evidence documenting the relationships between parenting and child development, the proposed research sought to examine into the relationship between parental responsiveness and primary school pupils’ behavioural adjustment in Kisii Central Sub-County, Kenya.

2. Research Methodology

- The study employed a mixed method approach (Creswell, 2014). This involved the collection, analysis and integration of both quantitative and qualitative research methods within a single research study in order to answer research questions (Creswell & Plano, 2011). Within the mixed method approach, the embedded research design was employed. The target population comprised of 14876 classes 7 and 8 primary school pupils, 10582 parents, 229 deputy head teachers and 218 guidance and counselling teachers. To obtain the sample for the study, the study used cluster sampling, stratified sampling and simple random sampling techniques. The sample size for the study consisted of 374 pupils, 30 parents, 30 deputy head teachers and 30 guidance and counselling teachers. The study employed questionnaires and interview schedules to gather information to address the research objectives. The Paulson’s Responsiveness Scale (PRS; 1994) was modified to measure parental responsiveness while the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (4-16 year old version) was modified to measure behavioural adjustment among primary school pupils. The study also employed the One-on-One interviews and focus group interviews.To ensure validity of research instruments in the present study, face, construct and content validities of the questionnaires, interview schedules and document analysis was determined by presenting and discussing the various items in research instruments with two experts in the school of Education of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST) who were actually the PhD thesis supervisors. The supervisors gave their views on the relevance, clarity and applicability of the questionnaire scales, interview schedule guides and document analysis guide. Their suggestions, together with the findings from the pilot study were used to modify the items in the research instruments. This ensured that the test items were clear, relevant and well organized. The study further adopted the triangulation approach so as to ensure the validity of the research instruments. The study gathered both quantitative and qualitative data. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used in analysing quantitative data while thematic analysis was used to analyse qualitative data.

3. Findings and Discussion

- To examine whether there was any statistical relationship between parental responsiveness and learners’ behavioural adjustment, the null hypothesis was tested. The hypothesis state:H0: There is no statistical significant relationship between parental responsiveness and learners’ behavioural adjustment.To achieve this, a Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient was calculated and table 1 shows the correlation analysis results in SPSS output.

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Drawing from the present study’s findings, it can be concluded that families represent the primary setting in which most children’s lives are shaped and determined. Central to the process of the socialisation of children are the parental nurturing practises which is characterised with responsiveness. Within these family contexts, children gradually internalise social standards and expectations which facilitate self regulation skills and responsibility. To a larger extent, the absence parental responsiveness was found to foster behavioural maladjustment among students in learning institution and home. Further, it can be concluded that parental responsiveness is a significant predictor of behavioural adjustment among primary school pupils. However with a lot of concern, the findings of the present study indicate that a good number of parents were not responsible hence they did not provide their children with a healthy social and emotional environment that would facilitate well adjusted behaviours among their children. However, children growing up in a positive home environment characterised with parental responsiveness were less likely to indulge in risk taking behaviour. In this regard, parental responsiveness was found as one of the necessary emotional component for parent-child interaction. Therefore, children need parental emotional support, trustworthiness, understanding and physical support as they navigate various developmental challenges and tasks. On the same note, it can be concluded that children who are raised in families where parents are unresponsive, their children were more prone to suffer from social and emotional incompetence. In light of the findings that parental responsiveness predicted pupils behavioural adjustment in the current study, the study recommends that The board of management of primary school, teacher and government should organize seminars that will equip parents with skills of provide emotional support to their children by responding compassionately when their children are distressed and take time to understanding their children’s emotions, feelings, beliefs and desires.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML