-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2018; 4(1): 8-12

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20180401.02

Gender Differences in Academic Achievement among Returnee Students in Kenyan Secondary Schools

Dorine A. Juma1, Peter J. O. Aloka2, Philip Nyaswa3

1Faculty of Education, Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Kisumu Campus, Kenya

2Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, School of Education, Bondo, Kenya

3Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Kisumu Campus, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter J. O. Aloka, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, School of Education, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study investigated gender differences in academic achievement among returnee students in Kenyan secondary schools. The study is informed by two theories, the Tinto’s Student Integration Theory and Transformative Learning Theory. The study was located in the mixed methods paradigm and within it the Concurrent Triangulation design was used. The target population for the study comprised 80 secondary schools in Rachuonyo south sub county (5 Extra county, 9 county and 69 sub county schools), 583 teachers (391 males and 192 females), 80 head teachers, 1 Sub-County Education Officer, 500 returnee students. The sample size of the study comprised 200 returnee students (40%), 20 principals (25%), 1 Sub-County Education Officer (100%), 100 teachers (17%), and 20 secondary schools (25%). The researcher employed questionnaires, interview guide, and interview guides to collect data. The researcher consulted with experts in research to ensure validity of instruments. To ensure reliability, the researcher used internal consistency method and a cronchbar alpha of r = 0.740 was reported. The data was analyzed using quantitative and qualitative techniques. The study findings were that there was statistically significant difference [t (168) = -2.317, p=.022] in academic achievement between gender. The study recommends that School principals should initiate academic mentorship programs for the returnee students in school.

Keywords: Gender Differences, Academic Achievement, Returnee Students, Kenya, Secondary Schools

Cite this paper: Dorine A. Juma, Peter J. O. Aloka, Philip Nyaswa, Gender Differences in Academic Achievement among Returnee Students in Kenyan Secondary Schools, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2018, pp. 8-12. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20180401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The right to education is a fundamental human right. Every individual irrespective of race, gender, nationality, ethnic or social origin, religion or political preference, age or disability, is entitled to equitable and successful completion of education. The right to education is stipulated in a number of human rights documents including the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) Article 28, the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, (Article 11), which Kenya has been committed to. A study carried out by [1] noted that secondary education is seen today as being critical for economic development and poverty reduction in Sub Saharan Africa. It against this background that most ministries of education in some African countries have put in place a number of measures to ensure that, in accordance with their re-entry policies, adolescents are admitted and retained in the educational system in line with national, regional, and international goals under various frameworks. These include, the education for all Goals, the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), and a number of international conventions. The right to education is one of the human rights entrenched in a number of international and regional human rights instruments. It is key because, it gives way to the protection of other rights. Article 26 of the United Nations universal declaration of human rights states that education is a human right. The United Nations convention on the rights of the child (CRC), article 28, as well attests to this right.In response to this, the Kenyan government has taken steps to actively enhance return to school policy among her citizens. For example, in 2003, when NARC government took over power in Kenya, the return to school policy was enacted. This led to many older/mature students reporting back to school after the introduction of Free Primary Education (FPE) and Free Secondary Day Education (FDSE) in all Kenyan public schools. Several cases of older students returning to Kenyan schools have been witnessed for some time now. This could be either due to several reasons. For example, [14] reported a case of a Mr Kimani Ng'ang'aMaruge, 88, who was the oldest man in Kenya to attend primary school. At the time of his enrolment in 2003, the Guinness Book of World Records listed him as being the oldest person in the world to start primary school. [12] also reported that a 90 year old grandmother returned to school to continue with her primary schooling. She had served in Rift Valley region as a midwife for the previous 65 years. When asked, she reported that, she wanted to know how to read and write, an opportunity she never had when she was a child. Many other female students have also reported back to school after delivery of their babies following the Kenyan government directives. In Rachuonyo south sub-county, there are several students who have gone back to school due to the return to school policy.School heads were also directed to readmit girls who became pregnant once they deliver. The Ministry of Education has warned of stern disciplinary action against head teachers who defy the directive. The then, Education assistant minister Ayiecho Olweny said hundreds of pregnant school girls in different parts of the country end up getting wasted after being denied admission. He said the ministry wanted all girls who dropped out over pregnancy allowed back without conditions to complete their education. Prof Olweny, however, asked the girls to maintain discipline [2]. The enactment of return to school policy has changed the composition of students entering schools. Education has indeed changed since the introduction of FPE (Rankin, Sandefur, and Teal, 2007). In particular, the age profile of students has been affected by the introduction of FPE with older students entering or returning to school. For example, the proportion of students who are at least one year older than the regular age in grade 8 has increased from 28% to 48% between 2002 and 2004 and there is at least anecdotal evidence from teachers that this leads to disciplinary problems. This is certainly confirmed in Kenya where re-entry rates of 7.7% at primary level, 23.4% at secondary and 25.1% at tertiary level have been reported. Cases of students returning to secondary schools in Rachuonyo South sub-county have been reported for some time now.The study was informed by two theories, the Tinto’s Student Integration Theory and Transformative Learning Theory. The Tinto’s theory of academic and social integration has provided a framework for researchers studying student success and persistence. A multitude of studies using Tinto’s theory have documented those students who are integrated into the academic and social life of institution exhibit positive outcomes [6]. Transformative learning theory seeks to explain the cognitive, affective and operative dimensions of adult learning. Often portrayed as a rational, cognitive conception, more recent interpretations now incorporate the affective, emotional and extra rational dimensions of personal change. These interpretations include a constructivist-developmental conception [3]. [9] show the existence of gender difference in variables under consideration, with girls showing internal locus of control, using attitude, motivation, time management, anxiety, and self-testing strategies more extensively, and getting better marks in Literature. With boys using concentration, information processing and selecting main ideas strategies more, and getting better marks in mathematics. Results suggest that differences exist in the cognitive-motivational functioning of boys and girls in the academic environment, with the girls have a more adaptive approach to learning tasks. The above reviewed study was done among regular students only not among returnee students as is the case of the present study.[10] revealed that females performed better than males in every subject. [5] determined whether there are significant gender differences in academic performance among undergraduate students in a large public university in Turkey. The paper finds that a smaller number of female students manage to enter the university and when they do so, they enter with lower scores. However, once they are admitted to the university, they excel in their studies and outperform their male counterparts. [13], results indicated that there was no significant differences exist between gender and Academic performance in Colleges of Education in Borno State, in favour of female students therefore, the null hypothesis was accepted. [2] study revealed the following findings; gender was strongly associated with mathematics achievement (r= 0.9880, p< 0.05). As a result, boys’ schools performed better than girls schools. Boys had a stronger affinity and interest towards mathematics. The study was only quantitative in nature and it had no qualitative findings. Therefore, the present study filled in gaps in literature by adopting both quantitative and qualitative methods.[1] reported no statistically mean difference between male and female students was found in regional examination both in average result and subject wise analysis. The proportion of male and female students both in the top and lower achieving groups was not statistically different. [8] found no significant difference in the academic performance in terms of gender in multiple choice questions (p=0.811) and short essay questions (p=0.515). There was no significant difference between the academic performance of male and female students. Literature examining the return to school by students who have been out of school and academic difficulty that such students experience in school has been ongoing for several decades. Studies comparing returning and regular students academically as well as on outcomes of success have been carried out in the world, Africa and Kenya. While some studies of social and academic integration exist in world studies, they are much fewer in number in the Kenyan context and none in particular in the Rachuonyo South sub-county schools.

2. Research Methodology

- The study was located in the mixed methods paradigm and within it the Concurrent Triangulation design was used. In this design, both the quantitative and qualitative data are collected and analyzed at the same time, happening in one phase of the research study and the researcher therefore gives equal priority and weights to both components [4]. The target population for the study comprised 583 teachers (391 males and 192 females), 80 head teachers, 1 Sub-County Education Officer, and 500 returnee students. The sample size of the study comprises 170 returnee students (34%), 20 principals (25%), 1 Sub-County Education Officer (100%), 100 teachers (17.2%), and 20 secondary schools (25%). The sample size was considered appropriate since Gay (2006) recommended that for a study, the sample size should range between 10-20%. The students and teachers were selected using the simple random sampling technique. The researcher employed questionnaires, interview guide, and interview guide to collect data. Questionnaires were used to collect data from students while interview guide were used to collect data from the guidance and counselling teachers. Interview guide on the other hand were used to collect information from the school principals and the District Education Officer. Validity of the research instruments was ensured by expert judgment by the university supervisors. In this study, internal consistency reliability of the instruments was obtained by computing Cronbach’s alpha (α) using SPSS. Quantitative data was analyzed using independent samples t-test while qualitative data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

3. Findings & Discussion

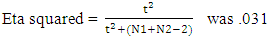

- The second objective of the study was to establish the gender differences in the academic achievement among returnee secondary school students. This objective was investigated by the use of an independent samples t-test. An independent-samples t-test was suitable method of statistical analysis because it is used when there is need to compare the mean score, on some continuous variable, for two different groups of subjects. An independent-sample t-test theory in the form of

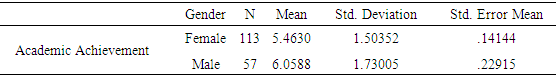

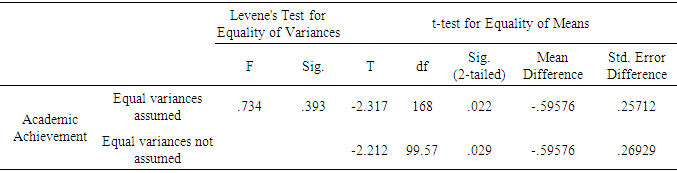

. In the present study, 113(66.5%) females and 57 (33.5%) males participated. When the means in academic achievement of each gender were computed as shown in the descriptive analysis shown in Table 1, it was clear that the form

. In the present study, 113(66.5%) females and 57 (33.5%) males participated. When the means in academic achievement of each gender were computed as shown in the descriptive analysis shown in Table 1, it was clear that the form  was achieved given that;

was achieved given that;  and

and  .

.

|

|

Hence, from the Eta squared = .031, it is concluded that the proportion of variance of the student returnee academic achievement that was explained by the gender was plausible. About three percent (3.1%) of the variance noted in academic achievement among the returnee students was affected by the gender of the student, with the male student favored to perform better than the female counterpart. This finding disagrees with [8] who reiterated that there was no significant difference in the academic performance in terms of gender in multiple choice questions (p=0.811) and short essay questions (p=0.515). There was no significant difference between the academic performance of male and female students.Qualitative data was also obtained on gender differences in academic performance of returnee students, the participants also reported mixed findings. However, most participants were of the opinion that boys did better than girls in academic work in school. Most respondents believed that boys were much more prepared when they returned to school, were much more focused and had self-direction as compared to girls. Other participants also reported that girls performed poorly because they had several challenges to overcome at school, emotional issues of attachment to the baby which made them not to concentrate in class. For example, some participants reported that:“Boys do better than girls when they return to school. Girls even here really struggle to do well in academics. The girls who return to school are faced with several challenges and hence they have difficulty in academic work here at school. Boys are fine and they come back when they are very serious with their academic work” (principal, 13)“in academic achievement, the boys who return back to school do much better than girls. Girls suffer from low self-esteem, stigma, are labeled especially if others know the kids they have at home. Some students even ridicule girls that they are mothers to so and so…” (principal 14)“The returnee students who are boys cope faster in academic work and they do much better than girls. Girls you know have to struggle emotionally with the absence of the baby at home. At times, girls ask for permission to go home to meet their children even if lessons are underway. They can’t concentrate as much as boys do and that’s why they don’t perform well in academics” (principal 10)“Boys perform better than girls simply because the boys have got lesser burdens to bear as opposed to the girls who now have an additional responsibility of taking care of their babies at home too” (teacher, 6)“Boys are comparatively better than girls, since most girls dropped out because of pregnancy and therefore with their return, they are still mothers at home when not in school. While most boys come back a little bit focused because of hard life experienced in accessing money” (teacher, 3)“The boys who have re-entered school work harder than the girls and are high achievers thus they perform better. However, most returnee girls are below average in terms of academic achievement while boys are mostly average” (teacher, 2)From the interview experts above, there were gender differences in academic performance. This finding agrees with [9] who examined gender differences existing in various cognitive motivational variables and in performance attained in school subjects of Literature and Mathematics. The study reported that existence of gender difference in variables under consideration, with girls showing internal locus of control, using attitude, motivation, time management, anxiety, and self-testing strategies more extensively, and getting better marks in Literature. With boys using concentration, information processing and selecting main ideas strategies more, and getting better marks in mathematics. Results suggest that differences exist in the cognitive-motivational functioning of boys and girls in the academic environment, with the girls have a more adaptive approach to learning tasks. However the finding disagrees with [10] who reported that females performed better than males in every subject. The reasons for the differences noted in this study are largely because of sociological factors. Similarly, [13] also disagrees that there was no significant differences exist between gender and Academic performance in Colleges of Education in Borno State, in favour of female students.On the other hand, some participants reported that there were no gender differences in the academic performance of the returnee students. The participants reported that both boys and girls who were returnee students performed to the same level on returning to school. Some interview excerpts are:“There are no significant gender differences in performance of both boys and girls. In our school, we have girls who are mature and came back after giving birth. Such girls are very organized in whatever they do, act like mothers to other girls and are much disciplined. Boys too are very keen on passing exams and as such their performances are just at the same level” (teacher, 7)“In most cases, both boys and girls just perform at the same level if they are returnees. This is because they face same challenges that affect their academic performance. Girls struggle with self-esteem which is now lower but boys are affected too in their own ways” (principal, 12)From the excerpts above, some respondents were of the opinion that both gender perform at the same level. This was because both genders had their own unique challenges and none was above the other. This finding disagrees with [2] who reported that gender was strongly associated with mathematics achievement. As a result, boys’ schools performed better than girls schools. Boys had a stronger affinity and interest towards mathematics.

Hence, from the Eta squared = .031, it is concluded that the proportion of variance of the student returnee academic achievement that was explained by the gender was plausible. About three percent (3.1%) of the variance noted in academic achievement among the returnee students was affected by the gender of the student, with the male student favored to perform better than the female counterpart. This finding disagrees with [8] who reiterated that there was no significant difference in the academic performance in terms of gender in multiple choice questions (p=0.811) and short essay questions (p=0.515). There was no significant difference between the academic performance of male and female students.Qualitative data was also obtained on gender differences in academic performance of returnee students, the participants also reported mixed findings. However, most participants were of the opinion that boys did better than girls in academic work in school. Most respondents believed that boys were much more prepared when they returned to school, were much more focused and had self-direction as compared to girls. Other participants also reported that girls performed poorly because they had several challenges to overcome at school, emotional issues of attachment to the baby which made them not to concentrate in class. For example, some participants reported that:“Boys do better than girls when they return to school. Girls even here really struggle to do well in academics. The girls who return to school are faced with several challenges and hence they have difficulty in academic work here at school. Boys are fine and they come back when they are very serious with their academic work” (principal, 13)“in academic achievement, the boys who return back to school do much better than girls. Girls suffer from low self-esteem, stigma, are labeled especially if others know the kids they have at home. Some students even ridicule girls that they are mothers to so and so…” (principal 14)“The returnee students who are boys cope faster in academic work and they do much better than girls. Girls you know have to struggle emotionally with the absence of the baby at home. At times, girls ask for permission to go home to meet their children even if lessons are underway. They can’t concentrate as much as boys do and that’s why they don’t perform well in academics” (principal 10)“Boys perform better than girls simply because the boys have got lesser burdens to bear as opposed to the girls who now have an additional responsibility of taking care of their babies at home too” (teacher, 6)“Boys are comparatively better than girls, since most girls dropped out because of pregnancy and therefore with their return, they are still mothers at home when not in school. While most boys come back a little bit focused because of hard life experienced in accessing money” (teacher, 3)“The boys who have re-entered school work harder than the girls and are high achievers thus they perform better. However, most returnee girls are below average in terms of academic achievement while boys are mostly average” (teacher, 2)From the interview experts above, there were gender differences in academic performance. This finding agrees with [9] who examined gender differences existing in various cognitive motivational variables and in performance attained in school subjects of Literature and Mathematics. The study reported that existence of gender difference in variables under consideration, with girls showing internal locus of control, using attitude, motivation, time management, anxiety, and self-testing strategies more extensively, and getting better marks in Literature. With boys using concentration, information processing and selecting main ideas strategies more, and getting better marks in mathematics. Results suggest that differences exist in the cognitive-motivational functioning of boys and girls in the academic environment, with the girls have a more adaptive approach to learning tasks. However the finding disagrees with [10] who reported that females performed better than males in every subject. The reasons for the differences noted in this study are largely because of sociological factors. Similarly, [13] also disagrees that there was no significant differences exist between gender and Academic performance in Colleges of Education in Borno State, in favour of female students.On the other hand, some participants reported that there were no gender differences in the academic performance of the returnee students. The participants reported that both boys and girls who were returnee students performed to the same level on returning to school. Some interview excerpts are:“There are no significant gender differences in performance of both boys and girls. In our school, we have girls who are mature and came back after giving birth. Such girls are very organized in whatever they do, act like mothers to other girls and are much disciplined. Boys too are very keen on passing exams and as such their performances are just at the same level” (teacher, 7)“In most cases, both boys and girls just perform at the same level if they are returnees. This is because they face same challenges that affect their academic performance. Girls struggle with self-esteem which is now lower but boys are affected too in their own ways” (principal, 12)From the excerpts above, some respondents were of the opinion that both gender perform at the same level. This was because both genders had their own unique challenges and none was above the other. This finding disagrees with [2] who reported that gender was strongly associated with mathematics achievement. As a result, boys’ schools performed better than girls schools. Boys had a stronger affinity and interest towards mathematics. 4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- It was also concluded that there is significant difference in academic achievement among the returnee students, with the male returnee students having better academic achievement scores than their female counterparts. School principals should initiate academic mentorship programs for the returnee students in school. This is because the qualitative data from interviews indicated that the returnee students had many challenges in and out of school. The themes included stigmatization, inadequate financial support, over-confidence, low self-esteem, social withdrawal and indulgence in sexual relationships with other students. The parents should be sensitized on the plight of returnee students in school. This is because the findings reported that the strategies of assisting returnee students include assignment of responsibility in school, provision of group counseling, provision of scaffolding to returnee students and sensitization to parents and the community.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML