-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2017; 3(2): 40-48

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20170302.02

Influence of Gender on Job Satisfaction of Secondary School Teachers in Kenya

Esther K. Mocheche, Joseph Bosire, Pamela Raburu

School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Pamela Raburu, School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

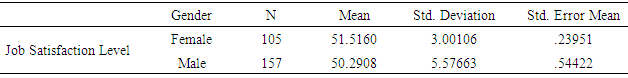

This study investigated the influence of gender on job satisfaction of secondary school teachers in Kisii Central Sub-County, Kenya. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Herzberg’s two factor theories formed the basis for the present study. The study’s target population consisted of all the 903 secondary school teachers, and a sample of 306 was selected by stratified sample from all the categories of secondary schools (National, Extra County, County and Sub-County) followed by stratification according to gender. Twelve secondary school principals participated in the qualitative study who were purposively selected. The study adopted an ExPostFacto research design where a mixed method research approach was adopted. Data collection tools were a modified from Sorensen self-esteem scale, job descriptive index questionnaire and interview schedule. Validity of the questionnaires was ensured by expertise judgment from university lecturers while for internal consistency and reliability, coefficient of 0.764 was obtained. Quantitative data was analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics while qualitative data was analyzed using Thematic analysis. Descriptive statistics of job satisfaction among gender, indicated that the female teachers had slightly higher score of 51.52, with a standard deviation of 3.0 and standard error of .240 in job satisfaction, compared to the male teachers who had a mean score of 50.29, with a standard deviation of 5.58 and standard error of .544 in the level of job satisfaction. The findings recommend that the Teachers’ Service Commission should consider recruiting more female teachers given that the female teachers enjoyed a relatively higher job satisfaction compared to the males. The Teachers’ Service Commission should in addition, consider giving opportunities to female teachers for leadership positions.

Keywords: Gender, Job satisfaction, Secondary school teachers

Cite this paper: Esther K. Mocheche, Joseph Bosire, Pamela Raburu, Influence of Gender on Job Satisfaction of Secondary School Teachers in Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2017, pp. 40-48. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20170302.02.

1. Introduction

- Job satisfaction is a major concern in the world, and Kinman & Wray (2014) describe teaching as an emotional activity whereby teachers experience emotional exhaustion, burnout and depersonalization. The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2009) highlights that half of the world's countries need to expand their teaching forces in order to be able to enroll all primary school-age children by 2015. Countries not only in Sub-Saharan Africa have by far the greatest need for additional teachers. Countries like Ireland, Spain, Sweden and the USA are pointed out as facing teaching gaps. In Sweden, prognoses indicate that the number of certified teachers in the compulsory school will be too low to cover the demand during the next 20 years. In 2020, the Swedish educational system will, according to national statistics, lack roughly 22,000 teachers, approximately 20% of the teaching workforce (Swedish National Agency for Higher Education, 2012).Parasuraman, Uli and Abdullah, (2009) study in Malaysia highlights that very few organizations have made job satisfaction a top priority, because of failure to understand the significant opportunity that lies in front of them where organizations that create work environments that attract, motivate and retain hardworking individuals will be better positioned to succeed in a competitive environment that demands satisfied and motivated teachers. In addition, Parasuraman et al., (2009) point out that a large part of one’s life is spent in the work place and it can be said that working life should be pleasant for someone and unhappiness with work life influences both work life and other sections of the human life, and that the male respondents had a relatively higher level of job satisfaction compared to female respondents. However, the differences in job satisfaction between males and females job satisfaction are not clear in Kisii Central Sub County.Job satisfaction is as important in the teaching profession as it is in any other profession where a professionally satisfied school teacher has a friendly attitude, greater enthusiasm and a higher value pattern and such school teachers contribute immensely towards the educational advancement of the students, whereas a dissatisfied school teacher is generally found to be irritable, depressed, hostile and neurotic in his attitude and such dissatisfied school teachers often makes the life of his/her students miserable, thereby causing a great harm to the institution as well as to the society (Sankar & Vasudha, 2015). In another study in Nigeria, Akomolafe & Ogunmakin (2014) emphasized that the consequences of job dissatisfaction are absenteeism from schools, turnover, aggressive behavior towards colleagues and learners, early exit from the teaching profession and psychological withdrawal from work.In a study in Kenya, Maara Sub-County, Muguongo, Muguna & Muriithi (2015) observed that compensation plays an important role in determining employees’ job satisfaction, and the perception of being paid what one is worth predicts job satisfaction. However, it was not clear from the study on the influence gender on teachers’ job satisfaction to cause the many stand offs. Similarly, Njiru (2014) study in Kenya found out that effective teaching to realize educational objectives demanded motivated and satisfied teachers yet majority of teachers in Kenya have portrayed lack of motivation in their places of work. However, it is not known whether gender has an influence on job satisfaction. Wachira & Gathungu (2013) studied job satisfaction factors that influence the performance of secondary school principals in their administrative functions in Mombasa District, Kenya. Part of the results indicated that principals had a low level of job satisfaction (10%). Other studies (George, Louw & Badenhorst, 2008; Strydom, Nortje, Beukes & Van der, 2012) indicated that teachers had an average job satisfaction which did not differ on grounds of gender. Although several studies (Parasuraman et al., 2009; Wachira & Gathungu, 2013; Njiru, 2014; Kabugaidezea, Mahlatshana & Ngirande, 2013 and Kinman & Wray, 2014) have been carried out in the education sector, none has been done to investigate the influence gender on job satisfaction of secondary school teachers in Kisii Central Sub-county, Kenya. The present study was informed by two theories; Maslow’s and two factor theory by Herzberg. Maslow (1954) attempted to synthesize a large body of research related to human motivation, and prior to Maslow (1954), researchers focused separately on such factors as Biology; achievement or power to explain what energizers directs and sustains human behavior. Maslow (1954) posited a hierarchy of human needs based on two groupings; deficiency needs and growth needs. Within the deficiency needs each lower need must be met before moving to the next higher level. Once each of these needs has been satisfied, if at some future time a deficiency is detected, the individual will act to remove the deficiency. Herzberg, Mausner & Snyderman (1959) published a two-factor theory of work motivation. Herzberg’s two-factor theory (also known as the motivator – hygiene theory) attempts to explain, satisfaction and motivation in the workplace. This theory states that satisfaction and dissatisfaction are driven by different factors- motivation and hygiene factors respectively. The basic tenets of Herzberg’s (1959) two factor theory are that job satisfaction and dissatisfaction are separate issues; satisfaction only comes from factors intrinsic to work itself. Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory has been linked to that of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory as it suggests that Maslow’s higher-order needs are similar to Herzberg’s satisfier factors, and Maslow’s lower-order needs are similar to Herzberg’s hygiene factors. According to Herzberg, et al., (1959), motivation factors are internal factors that are associated with higher-order needs, and include the opportunity to achieve in the job, recognition of accomplishment, challenging work and growth options, responsibility in the job, and the work itself – if the work is interesting. The presence of intrinsic factors or motivators lead to job satisfaction, but their absence will not lead to job dissatisfaction.Several studies (Fitzmaurice, 2012; Kabugaidezea & Mahlatshana, 2013; Popoola & Oluwole, 2007; Okoko, 2012 and Njiru, 2014) studied the effects of gender on job satisfaction and most studies’ results have shown that females were more satisfied. In a study in Spain, Briones, Tabernero & Arenas (2010) examined the effects of several demographic and psycho-social factors involved in teachers’ job satisfaction in Madrid and Almeria. The sample consisted of 68 secondary school teachers in cultural diversity settings to cater for different communities in Kenya. “Their average age was 43.56 years old (SD=10.93); 60.3% were women and 38.2% were men” (Briones, et al., 2010 P. 119). Path analyses showed that the teachers’ job satisfaction was significantly and positively related to personal achievement and perceived support from colleagues, and significantly and negatively related to emotional exhaustion. The teachers’ self-efficacy was an indirect predictor of job satisfaction, and a direct predictor of personal achievement and perceived support from colleagues.In a study by Fitzmaurice (2012) job satisfaction in Ireland was explored with a sample 115 participants. The data was analyzed using independent sample, t-test. Results indicated that females were more satisfied with their jobs than males. Analysis of variances was conducted in order to compare job satisfaction and the predictor variables against gender. There was a significant difference in the scores for males and females. “The mean score for job satisfaction in relation to males was 142.1667 (SD = 22.28379) and for females was 147.2985 (SD = 26.81531), indicating that female participants experienced greater job satisfaction” (Fitzmaurice, 2012 P. 34). An independent sample t-test further recommended another study on factors other than age, gender and marital status. In another study, Parasuraman et al., (2009) investigated the empirical evidence on the differences in the job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Sabah, Malaysia where a sample size of 200 was included in the study. T-tests and F-tests (ANOVA) were used. The teachers’ job satisfaction was determined by two separate measures namely overall and facet specific overall job satisfaction. The work dimension factors were clustered into six and comprised of pay, working conditions, co-workers, promotion, work itself and supervision. Analysis of variances was conducted in order to compare job satisfaction and the predictor variables against gender. There was a significant difference in the scores for males and females. “The mean score for job satisfaction in relation to males was 142.1667 (SD = 22.28379) and for females was 147.2985 (SD = 26.81531), indicating that female participants experience greater job satisfaction” (Parasuraman et al., 2009 P. 14). An independent sample t-test further supported this hypothesis. This study revealed that secondary school teachers in Tawau, Sabah were generally satisfied with their job; there was a significant relationship between job satisfaction and gender, whereby the female teachers were generally more satisfied than male teachers. Ngimbudzi (2009) studied job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Tanzania. With a sample that comprised 162 teachers (N=162) using a non-probability sampling procedure, the convenience sampling was adopted in selecting the study sample. The research question sought to investigate or explore whether there were any significant differences in teachers’ job satisfaction in relation to demographic factors or teacher characteristics (gender, age, and marital status, teaching experience, school type, school location, promotional position and educational qualifications). T-test was used to determine whether male teachers and female teachers differed significantly in their job satisfaction. Using the t-test for independent samples, it was found that there were significant differences between male and female teachers with regard to job satisfaction in two job dimensions: Job Characteristics and Meaningfulness of the Job. “In the satisfaction with job characteristics was statistically significant (t=2.887, df=156, p<0.05). More male teachers (mean=17.3) than females (mean=14.9) were satisfied with job characteristics. Whereas, satisfaction with meaningfulness of the job was statistically significant (t=2.325, df =156, p<0.05). More male teachers (mean=7.3) than female teachers (mean=6.55) were satisfied with meaningfulness of the job” (Ngimbudzi, 2009 P. 71).In another study, Njiru (2014) investigated job satisfaction and motivation among teachers in Kenya. The study design was a descriptive survey and questionnaires and interview schedules were used to collect data. Data was analyzed using t-tests and analysis of variance at 0.05 level of significance and the results indicated that females were more satisfied with jobs in which they could interact with others in a supportive and co-operative way, even though the jobs were only minimally demanding and challenging. “Out of 30 teachers who participated in the study, 17(56.7%) were male while 13(43.3%) were female” (Njiru, 2014 P. 140). Female teachers had significantly higher levels of job satisfaction than their male counterparts.

2. Research Methodology

- This study adopted the Ex Post Facto research design which Lammers & Badia (2005) define as a research design in which the independent variable or variables have already occurred and in which the researcher starts with the observation of the dependent variable or variables in retrospect for their possible relations to and effects on the dependent variable or variables. This design was chosen because sometimes one wants to study things they cannot control, things they cannot ethically or physically control (Lemmers & Badia, 2005). In this study, gender already exists and cannot be changed. In addition, the study adopted a mixed method approach in which both qualitative and quantitative data were collected. Combining both quantitative and qualitative data enabled the researcher to best understand and explain a research problem (Creswell, 2014). This procedure seemed to capture the complexity of teachers' perceptions of their workplace conditions. A combination of quantitative and qualitative research therefore was a better option. Interviews assisted in achieving a more behaviorally related assessment of the participants' lives at work and a better indication of the exact factors that contributed to their levels job dissatisfaction (George et al., 2008). Target population for this study comprised all the public secondary school teachers in Kisii Central Sub-County. Kisii Central Sub-County has a total of 60 registered secondary schools (County Education Office, 2015) with a total of 903 secondary school teachers (Teachers’ Service Commission Kisii, 2015). A sample of 306 were selected, and 37 were sampled from a total of 110 in National Schools, 43 from 128 in the Extra County schools, 76 from 228 in County Schools and 150 from 437 in Sub County Schools. The study further stratified the sampled 306 according to gender, to ensure that both female and male teachers were represented (Creswell, 2014). Twelve secondary school teachers were also purposively selected participated in the qualitative study (Guest, Arwen & Laura, 2013).The present study used questionnaires (Job Satisfaction Questionnaire for Secondary School Teachers) and interview schedule to collect the required data. Questionnaires contained questions that the respondents were required to tick statements that best described them on a 5-Point Likert Scale where (1) ND-Not Dissatisfied (2) FD-Fairly Dissatisfied (3) MD-Moderately Dissatisfied (4) D-Dissatisfied (5) HD-Highly Dissatisfied. For the interview schedule, the same questions were asked to each interviewee in the same order in aspects that were in line with the study’s objective. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze quantitative data. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the levels of job satisfaction for male and female teachers. Qualitative data from the interviews was analyzed using Thematic Analysis (Creswell 2014). Verbatim quotations from interviews were transcribed, coded and themes and sub-themes emerged (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

3. Findings and Discussion

- In the present study, 157(59.9%) males and 105(40.1%) females participated. These results were further subjected to hypothesis testing using an independent sample t-test. The statistical model used was:

Where

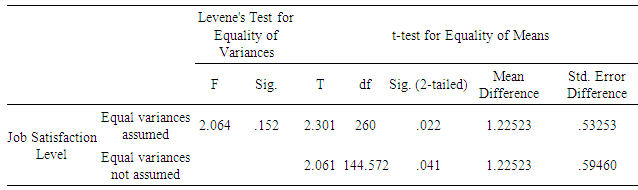

Where  represent sample means of female and male respectively.To address this objective of the study, the hypothesis “There is no gender difference in job satisfaction among secondary school teachers” was tested. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the levels of job satisfaction for male and female teachers, as indicated in Tables 1 and 2.

represent sample means of female and male respectively.To address this objective of the study, the hypothesis “There is no gender difference in job satisfaction among secondary school teachers” was tested. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the levels of job satisfaction for male and female teachers, as indicated in Tables 1 and 2.

|

|

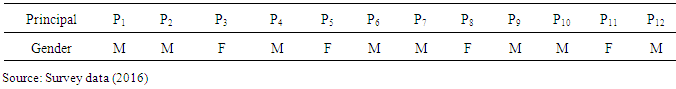

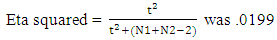

Hence, from the Eta squared = .02., it can be deduced that the proportion of variance of the level of teacher job satisfaction that was explained by the gender was plausible. Two percent (2.0%) of the variance noted in the level of job satisfaction was affected by gender of the teacher, with the female teacher favored to be happier as a secondary school teacher than the males. Based on the quantitative studies’ findings, this study agrees with a study in Ireland by Fitzmaurice (2012) whose findings revealed that females had significantly higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their male counterparts. In addition, in Kenya, a study by Njiru (2014) reported that females had higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their male counterparts. However, the current study contrasts the study in Nigeria by Popoola and Oluwole (2007) whose findings revealed no difference between the males and females in satisfaction. In addition, a study in Malaysia by Parasuraman et al., (2009) whose findings revealed that the males had a relatively higher levels of job satisfaction compared to the females. Twelve secondary school principals were interviewed and their gender is shown in Table 3.

Hence, from the Eta squared = .02., it can be deduced that the proportion of variance of the level of teacher job satisfaction that was explained by the gender was plausible. Two percent (2.0%) of the variance noted in the level of job satisfaction was affected by gender of the teacher, with the female teacher favored to be happier as a secondary school teacher than the males. Based on the quantitative studies’ findings, this study agrees with a study in Ireland by Fitzmaurice (2012) whose findings revealed that females had significantly higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their male counterparts. In addition, in Kenya, a study by Njiru (2014) reported that females had higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their male counterparts. However, the current study contrasts the study in Nigeria by Popoola and Oluwole (2007) whose findings revealed no difference between the males and females in satisfaction. In addition, a study in Malaysia by Parasuraman et al., (2009) whose findings revealed that the males had a relatively higher levels of job satisfaction compared to the females. Twelve secondary school principals were interviewed and their gender is shown in Table 3.

|

4. Conclusions

- A significant difference in levels of job satisfaction was found between male teachers and female teachers, with female participants reporting greater job satisfaction. Qualitative findings show that both male and female Principals were dissatisfied as a result of their gender where female Principals remarked that other people see them as a woman. Male teachers take an upper hand and in Board of Management meetings, female teachers feel frustrating especially when the men have somebody they want to impose in office. Similarly, most male Principals indicated that issues to do with handling females both teachers, parents and the community was a challenge where one could be easily framed and fixed and where widows wanted to pay fees in “kind”. The hypothesis stated:“There is no gender difference in job satisfaction among secondary school teachers” It was rejected, which meant accepting the alternative hypothesis;“There is gender difference in job satisfaction among secondary school teachers”

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML