-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2017; 3(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20170301.01

Medical Cannabis: In Medicine Perspective for Human

Selvarajah Krishnan1, Sheikh Muhamad Hizam2, Fikhri Norefendie2, Danail Shariran Hashim2, Nazrin Mazlan2

1International University of Malaya-Wales, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2Business School, University Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Selvarajah Krishnan, International University of Malaya-Wales, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Support for legalizing cannabis use and not simply for medical purposes has been rising steadily since the early 1990’s. Despite legal restriction, cannabis is often used to relieve chronic neurasthenic pain, and it carries psychotropic and physical adverse effect with a propensity for addiction. There are several medical benefits from the cannabis but this research focus to find out more about the cannabis as a medical purpose for human. In ensuring the stability of information generated questionnaires and investigation was conducted at the survey. Based on the result, we can conclude that cannabis have their some distinctive advantages in the treatment of human disease.

Keywords: Medical cannabis, Human health, Medical benefit

Cite this paper: Selvarajah Krishnan, Sheikh Muhamad Hizam, Fikhri Norefendie, Danail Shariran Hashim, Nazrin Mazlan, Medical Cannabis: In Medicine Perspective for Human, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20170301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Perhaps the greatest injustice produced by the current legislation with regard to cannabis is that relating to its potential medical usage. The usage of cannabis is largely governed under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and according to this it has no medical value. However, current scientific research and the testimonies of thousands of people from the past and present fully contradict this claim. Cannabis has been used as a medicine worldwide for at least 5000 years. It was part of the British Formula until 1971 when the Misuse of Drugs Act was passed, resulting in it being banned. The heyday of cannabis medicine was around the end of the nineteenth century, where it was used for a number of symptoms in a number of forms. The federal government classifies marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance, and for good reason. Marijuana in its smoked form is known to damage the brain, heart, lungs and immune system and impairs learning, memory, perception and judgment. Putting the word “medical” in front of marijuana doesn’t change the fact that it’s a harmful drug that causes a long list of health, criminal and societal problems. Legalizing its use for medicinal purposes, while perhaps well-inattention, will only worsen these problems and have terrible implications for our state.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Medical Cannabis

- The Compassionate Use Act of 1996 regulates medical marijuana in California. Medical Marijuana refers to the use of cannabis or marijuana, including constituents of cannabis, THC and other cannabinoids, as a physician-recommended form of medicine or herbal therapy. The Act ensures that under a physician’s recommendation, seriously ill Californians have the right to obtain and use marijuana for the treatment of cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, migraine, or any other illness for which marijuana provides relief. Any qualified patient or patients’ caregivers may possess or cultivate marijuana for personal medical use upon the written or oral recommendation or approval of a physician. If not for medical purposes, cultivation or processing of marijuana is punishable by up to sixteen months in state prison. Medical cannabis can refer to the use of cannabis and its cannabinoids to treat disease or improve symptoms; however, there is no single agreed upon definition. The use of cannabis as a medicine has not been rigorously scientifically tested, often due to production restrictions and other governmental regulations. There is limited evidence suggesting cannabis can be used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, and to treat chronic pain and muscle spasms. Its use for other medical applications, however, is insufficient for conclusions about safety or efficacy. Short-term use increases the risk of both minor and major adverse effects. Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, vomiting, and hallucinations. Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear. Concerns include memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, schizophrenia in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.

2.2. Human Health

- Fifty years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This definition should serve as a reminder that redefining the view of environmental health and the natural environment requires many shifts in thinking, as well as a willingness to pursue a diversity of approaches. Advances in the field of environmental health have taught us much about human health hazards; for example, air pollution can cause respiratory disease, heavy metals can cause neurotoxicity, global climate change is likely to fuel the spread of infectious diseases. Domestically, the response has been to clean up the environment, a laudable goal, said Rafe Pomerance of Sky Trust. Environmental health issues traditionally have been addressed at the international level within the context of such issues as ozone depletion, climate change, and biodiversity. Countries have tried to address these issues through the multilateral process, such as multilateral agreements and commissions, bilateral assistance and cooperation, private sector investment, trade, the work of nongovernmental organizations, education, and training.

2.3. Medical Benefit

- A New Look at the Scientific Evidence (Oxford University Press, 2005) said that the drug's popularity as a medicine spread throughout Asia, the Middle East and then to Africa and India, where Hindu sects used it for pain and stress relief. Medical marijuana is available in several different forms. It can be smoked, vaporized, ingested in a pill form or an edible version can be added to foods such as brownies, cookies and chocolate bars. It is exceptionally difficult to do high-quality studies on its medicinal effects in the U.S., said Donald Abrams, an integrative medicine specialist for cancer patients at the University of California, San Francisco. Marijuana may have therapeutic effects is rooted in solid science, marijuana contains 60 active ingredients known as cannabinoids. The body naturally makes its own form of cannabinoids to modulate pain. The primary psychoactive cannabinoid in marijuana is THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol. THC targets the CB1 receptor, a cannabinoid receptor found primarily in the brain, but also in the nervous system, liver, kidney and lungs. The CB1 receptor is activated to quiet the response to pain or noxious chemicals. In a placebo-controlled, 2007 study in the journal Neurology, Abrams and his colleagues found that marijuana is effective at reducing neuropathic pain, or pain caused by damaged nerves, in HIV patients. Opiates, such as morphine, aren't effective at treating that sort of pain. Abram said. Researchers at the American Academy of Neurology have also found that medical marijuana in the form of pills or oral sprays seemed to reduce stiffness and muscle spasms in MS. The medications also eased certain symptoms of MS, such as pain related to spasms, and painful burning and numbness, as well as overactive bladder, according to the study published in the journal Neurology. A well-known effect of marijuana use is the “munchies,” so it has been used to stimulate appetite among HIV/AIDS patients and others who have a suppressed appetite due to a medical condition or treatment. Medical marijuana is also frequently used to treat nausea induced by chemotherapy, though scientific studies of the smoked form of the plant are limited.

3. Research Methodology

- For this research, we used secondary data to get information. Data was collected from a no probability, convenience sample composed of all clients in one California County identified as authorized medical marijuana users who were admitted to substance abuse treatment during the study time period. The comparison group consisted of all other county treatment clients with similar admission dates and primary drug use reported. While this could be considered a quasi-experimental comparison group design with no controlled randomization and a limited sample size, the study is best described as an exploratory pilot investigation due to the final sample size. All publicly funded substance abuse treatment agencies in California must report admission and discharge data to the State Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs via the California Outcomes Measurement System (CalOMS). While CalOMS has some limitations, noticeably in relation to specificity of treatment outcomes, it is the best available database for cohort comparisons across a range of domains. Access to county level CalOMS data was provided by the participating county as were specific data points for those clients certified as medical marijuana users (no personally identifiable data were presented to the researcher).This easy guide is intended to help patients and caregivers understand the different method of administration of medical marijuana, so that they can make educated decision about the products they purchase and try. Medical cannabis is a very effective medicine used by patients across the globe to treat and alleviate symptoms of many serious medical conditions that do not respond to traditional interventions. Studies have proven that cannabis has therapeutic properties that cannot be replicated by any other currently prescribed medications, and it induces far fewer and much less severe side effects than many commonly prescribed pharmaceuticals and over the counter drugs.

4. Finding

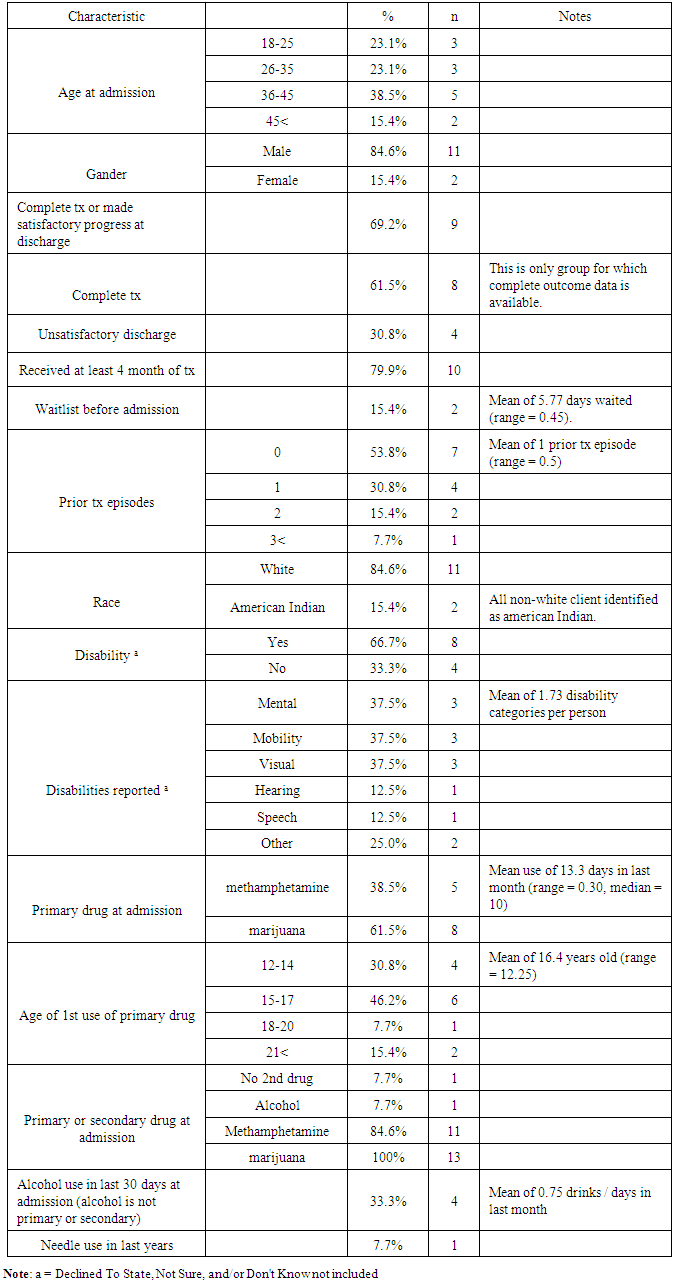

- Table below show presents major characteristics of the group of clients authorized to use marijuana during the course of substance abuse treatment (MM). As noted, the only group for which complete outcome data is available is the group that successfully completed treatment (n = 8). Though clinicians vary in their recommendations for the optimal length of treatment, it is generally accepted that the longer clients are engaged in treatment, the better their outcomes [23]. A very high percentage of the MM group who received at least four months of treatment completed or were discharged successful (80% [n = 8]), with a mean length for those completing treatment of five months, 8.4 days.

|

5. Conclusions

- The American College of Physicians position paper on "Supporting Research into the Therapeutic Role of Marijuana" references marijuana's analgesic qualities [8] while other sources address marijuana's potential in the context of mental illnesses, anorexia, nausea, and muscle spasticity [7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. How the findings described here relate to other studies on marijuana's potential as a therapeutic aid remains inconclusive. It is clear, however, that cannabis use did not compromise substance abuse treatment amongst the medical marijuana using group. In fact, medical marijuana users seemed to fare equal to or better than non-medical marijuana users in every important outcome category. Movement from more harmful to less harmful drugs is an improvement worthy of consideration by treatment providers and policymakers. The economic cost of alcohol use in California has been estimated at $38 billion [30]. Add to this the harm to individuals, families, communities, and society from methamphetamine, heroin, and cocaine, and a justification can be made for medical marijuana in addictions treatment as a harm reduction practice. As long as marijuana use is not associated with poorer outcomes, then replacing other drug use with marijuana may lead to social and economic savings. There are differences in public and professional perceptions about marijuana use. Thirty-two percent of Americans believe that addiction to marijuana is a danger to society. However, the Institute of Medicine is quite clear in saying, "Marijuana has not been proven to be the cause or even the most serious predictor of serious drug abuse" ([7], p. 10). Marijuana dependence may very well be problematic, but the Institute of Medicine also concluded "compared with alcohol, tobacco, and several prescription medications, marijuana's abuse potential appears relatively small and certainly within manageable limits for patients under the care of a physician" (p. 58). Further research on marijuana's effects on treatment outcomes can help address the disparity in disciplinary perceptions and decision-making.Hardly pro-marijuana lobbies, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Office of National Drug Control Strategy, and the State of California's Little Hoover Commission on California State Government Organization and Economy all make recommendations about substance abuse treatment services that are consistent with studying the potential for medical marijuana use in addictions care. For at least a decade the National Institute on Drug Abuse has maintained that drug addiction is a brain disease. California's Compassionate Use Act of 1996 (Section 11362.5 of California's Health and Safety Code) is equally clear that people "have the right to obtain and use marijuana for medical purposes where that medical use is deemed appropriate and has been recommended by a physician who has determined that the person's health would benefit from the use of marijuana in the treatment of cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, migraine, or any other illness for which marijuana provides relief" (emphasis added). Expanding the evidence-base for effective addiction treatments through a variety of treatment protocols continues to be worthy of attention from research and clinical communities. While it may sound contrarian to suggest that the federal government's National Drug Control Strategy might support research into the potential therapeutic effect of marijuana on problematic use of other drugs, the document emphasizes "the need for customized strategies that include behavioural therapies, medication, and consideration of other mental and physical illnesses". Considering marijuana in a medicinal context, the research described here offers a novel customized strategy. The National Drug Control Strategy goes on to note.This research project is notably limited. Primarily, MM group members were identified by persons working in the treatment setting, not through official documentation. Unfortunately, California does not require treatment providers to indicate the medical marijuana status of a client when CalOMS data is reported. MM group identities were confirmed on multiple occasions and by more than one program staff member (though the identities were not shared with the researcher). Aside from the small sample size, data gaps presented the other main limitation. CalOMS data for the control group is presented in aggregate, while the data for the MM group is much richer. This allows for more accurate representation of treatment outcomes for the MM group, but hinders the rigor of comparisons. So, for example, CalOMS reports client characteristics and treatment outcomes for all treatment episodes (service counts), while the MM group is only for the most recent treatment episode (unduplicated individuals). This means that CalOMS includes data on clients who moved in and out of treatment on multiple occasions. Also, CalOMS reports data on categories of discharge besides treatment completion, while the MM group only reports discharge information for treatment completers. Since the MM group n s were subtracted from the CalOMS reports for the entire county, this potentially included duplicated clients. There were 53 cases of "completed treatment" in the Non-MM group. The data comparing admission indicators to discharge indicators for this group included 67 cases. This suggests that discharge data were reported for 14 people who did not successfully complete treatment.Another limitation in the study relates to its quasi-experimental nature. The quantity of marijuana used by members of the MM group is unknown, as are other important factors including frequency of use, potency of product, level of contamination, and method of ingestion. So, for example, while the bulk of marijuana consumed in the United States is produced in Mexico it is more likely that the marijuana used in this study was secured from a regional source owing to the setting's geography. The American College of Physicians notes, "Examining the effects of smoked marijuana can be difficult because the absorption and efficacy of THC on symptom relief is dependent on subject familiarity with smoking and inhaling. Experienced smokers are more competent at self-titrating to get the desired results. Thus, smoking behaviour is not easily quantified or replicated" ([8], p. 35). Cannabidiol (CBD) content is as important for ascertaining the effect of marijuanauseas tetrahyrdocannabinol (THC). The lack of illness specific data limits the study's ability to draw powerful conclusions about marijuana's potential in addictions treatment. We know, for example, that CBD has some anti-psychotic and anti-anxiety properties. Yet the percentage of clients who used medical marijuana for psychiatric difficulties rather than, for example, chronic pain is unknown. The data does indicate that 50% (n = 3) of MM group treatment completers had a mental health diagnosis compared to 22% (n = 13) of the Non-MM group.

Suggestions for Further Research

- Expanded data collection is necessary while the "natural experiment" of authorized marijuana use continues in California. A very simple policy change, adding an additional question (i.e., Are you an authorized medical marijuana user? Yes/No) to the State of California's Outcomes Measurement System (CalOMS), would make rigorous data analysis possible by significantly increasing sample size. Clearly there are other questions related to marijuana use that would aid in any research project as well, such as frequency of use, potency of product, method of ingestion, and medical condition for which marijuana has been recommended. Though treatment clients currently participate in a lengthy interview at admission that generates data points for client characteristics, demographics, and patterns of behaviour, introduction of too many additional questions would likely prevent requisite legislative action. Sample size could be increased by involving additional counties at a higher level of engagement than that described here. Medical marijuana users themselves could also be recruited to participate in the research (for examples of medical marijuana user surveys see [19, 28, 29]. Most importantly, the study described here demonstrates a beginning methodology for determining medical marijuana's effects on substance abuse treatment outcomes. Research can be done even within legal and ethical constraints posed by cannabis research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML