-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2016; 2(3): 61-66

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20160203.02

The Effects of Commodification of Education on Emotional Labour amongst Private University Lecturers in Malaysia

K. Selvarajah T. Krishnan, Jaya Priah Kasinathan

Business & Law, International University of Malaya-Wales, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Correspondence to: K. Selvarajah T. Krishnan, Business & Law, International University of Malaya-Wales, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Emotional labour effects job satisfaction and work performance, hence directly impacting organization performance. Although there are studies on emotional labour, but studies on the relationship between the commodification of education and emotional labour amongst lecturers are not found. Simple random sampling was utilized and self-administered questionnaire distributed by mail to university lecturers in Peninsular Malaysia. The significance of the study will enable institutions of higher of learning to provide university lecturers with the needed support through emotional management and effective intervention which directly impacts job satisfaction and performance. The recognition and support by management will in turn increase students’ retention and satisfaction as well as improve overall university performance and business growth and sustainability.

Keywords: Commodification of Education, Emotional Labour, Malaysian University Lecturers

Cite this paper: K. Selvarajah T. Krishnan, Jaya Priah Kasinathan, The Effects of Commodification of Education on Emotional Labour amongst Private University Lecturers in Malaysia, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 2 No. 3, 2016, pp. 61-66. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20160203.02.

1. Introduction

- Education which is a public good is redefined to a commodity that is customer –oriented when it enters the market-place. “Subjecting a public good like education to commercial logic is generally disastrous,” warns McChesney (2013) and who argues that market-based values are fundamentally incompatible with education. The responsibility to constantly maintain the quality and competitiveness of this commodity is mostly borne by the academic staff. In line with this, commercialization of higher education has intensified the job characteristics and role of lecturers. Apart from teaching, a lecturer employed at a university is seen obligated to satisfying the students, keeping the ratings of the university as well to ensure the products (graduates) are well received in the labour market as productive (Hall, Swart & Duncan, 2013).The Malaysian government passed the Private Higher Education Act 1996 which allowed the expansion of private education in Malaysia (Hon-Chan, 2007). Today, there are 40 private universities around the country and according to the Malaysian Economic transformation programme the private education is a sector set to grow six-folds (Ideris, 2014). The transformation of the higher education industry from elitist to massification of education in Malaysia has proven to be a lucrative industry. According to Education NKEA, education is targeted to raise total Gross National Income contribution by RM 34 billion to reach RM 61 billion by 2020 (Ideris, 2014).The massification and commercialization of education, though contributes significantly to the country’s economy but it poses certain challenges especially to the academics. Many universities today around the world have transformed from being a public good to a private good, thus wholly changing the way it operates. The restructuring of higher education worldwide has seen the shift in thinking of education as a pure welfare or social good to one that is subject to market principles (Arokiasamy, 2011). Due to commodification, universities are increasingly being considered as service institutions and their students perceived as customers (Berry and Cassidy, 2013; Constanti & Gibbs, 2004). As found by Heskett, Sasser and Schlesinger (1997) in their Service-Profit Chain equation, the relationship between a university lecturer and their customers (students) could be a critical factor in the overall performance of the university. As a service organization, universities would have to pay much attention to the manner in which its employees (lecturers) perform at the customer/provider interface, to gain competitive advantage (Constanti and Gibbs, 2004). Therefore, university lecturers’ wellbeing, job satisfaction and job performance could be suggested as predicting factors for student satisfaction, student performance and student retention. Student satisfaction, student and university performance can be further suggested as predictive factors for a university lecturer’s level of job satisfaction and emotional labour level. The customer-driven system warrants that teaching staff perform emotional labour in order to mitigate the negative emotions and to avoid disgruntled customers. The execution of emotional labour is expected at the time of execution of duties, thereby becoming a surplus value to teaching and learning activity experienced by customers (Gaan, 2012).Unlike many other professions, due to commodification of education academicians are subjected to multiple and sometimes conflicting demands from other stakeholders, including students and external agencies such as employers and society at large (Ogbonna & Harris, 2004; Berry & Cassidy, 2013; Hall, Swart & Duncan, 2013) Demands made by customers, management and workload leads to exploitation of academicians and consequently to stress (Gaan, 2012). This study is aimed at seeking the relationship between effects of commodification and its impact to emotional labour amongst lecturers. The consequences of commodification to education would entail the conflicting demands by the stakeholders mainly students and management.

2. Literature Review

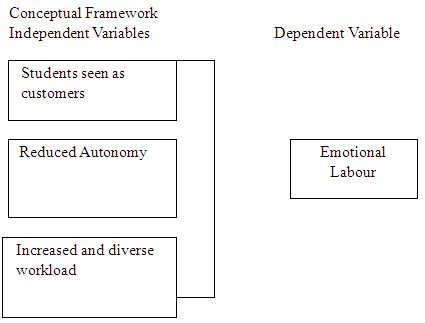

- Commodification of education happens when there is a market infused approach to education that treats knowledge as a commodity whose exchange value is measured crudely comparing the cost of acquiring a degree (tangible certification of “product” acquisition with financial earnings the degree supposedly enables (Schwartzmann, 2013). According to Sandel (2012) the reach of markets, and market-oriented thinking, into aspects of life traditionally governed by nonmarket norms is one of the most significant developments of our time. A significant consequence of commodification of education is the rise of managerialism in universities (Gaan, 2012). Review of scholarly works by (Willmott, 1995; Mok, 1997; Giroux 1999; Simkins 2000; Meyer 2002, O’Brien & Down, 2002; Constanti & Gibbs, 2004; Gaan, 2012; Berry & Cassidy, 2013) have highlighted the changing paradigm of education institution where is a focus on efficiency, quality, effectiveness, predictability and substitution of human technology with non-human technology (Ritzer, 1993). In addition, this new paradigm has also changed the role of the academician to one that is a service provider who treats students as a customer as she/he (the academic) aims to receive excellent ratings, thus continues tenure and research funding (Gaan, 2012). The increasing workload on academics is more associated with the increasing administrative work, accountability, performance management, and documentation along with increasing number of applicants. Commodification of education happens when there is a market infused approach to education that treats knowledge as a commodity whose exchange value is measured crudely comparing the cost of acquiring a degree (tangible certification of “product” acquisition with financial earnings the degree supposedly enables (Schwartzmann, 2013). According to Sandel (2012) the reach of markets, and market-oriented thinking, into aspects of life traditionally governed by nonmarket norms is one of the most significant developments of our time. A significant consequence of commodification of education is the rise of managerialism in universities (Gaan, 2012).Review of scholarly works by (Willmott, 1995; Mok, 1997; Giroux 1999; Simkins 2000; Meyer 2002, O’Brien & Down 2002, Constanti & Gibbs, 2004; Gaan, 2012; Berry & Cassidy, 2013) has highlighted the changing paradigm of education institution where is a focus on efficiency, quality, effectiveness, predictability and substitution of human technology with non-human technology (Ritzer, 1993). In addition, in this new paradigm it has also changed the role of the academician to one that is a service provider who treats students as a customer as she (the academic) aims to receive excellent ratings, thus continues tenure and research funding (Gaan, 2012). The increased workload on academics is more associated with the increasing administrative work, accountability, performance management, and documentation along with increasing number of applicants. According to Varca (2009), this kind of transition of role from academician to service provider generates incongruent demand within the role theory paradigm. As a result of this, there is a manifestation of conflict as the service provider violates the requirement of one role while fulfilling the demands of another. Therefore this conflicting or potential incompatibility between the individual’s authentic /real emotion and that which is desired by organization will cause the presence of emotional labour (Morris & Feldman, 1996).Emotional labour has been found to present in all jobs that are service oriented. Emotional labour has been defined as a state that exists when there is a discrepancy between demeanor that an individual displays and the genuinely felt emotions that would be appropriate to display (Mann, 1999; Berry and Cassidy; 2013). The prevalence of emotional labour is noted by Mann (2008) where it is performed in almost two-thirds of workplace interaction and the maintaining job standards and job target will also depend on how employees perform it. The role of emotion at workplace can be even stronger because various factors, including the interaction with supervisors, peers, and followers, generate affective experiences that have potential to influence subsequent behaviors (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Display of positive emotion by employees is directly related to customers’ positive affect following service encounters, and to their evaluation of service quality. Emotional labour is typified by the way roles and tasks exert overt control over emotional displays (Constanti and Gibbs, 2004). According to Sharma & Black (2001) emotional labour can foster both satisfaction and dissatisfaction for employees.According to studies service employees perform emotional labor using three acting techniques which are Surface Acting, Deep Acting and Genuine Acting (Hochschild, 1983; Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). When employees alter their outward appearance to simulate the required emotions—emotions that are not necessarily privately felt, they are said to be employing Surface Acting. The second acting mechanism is “deep acting.” Deep acting occurs when employees change not only their physical expressions, but also their inner feelings. This can be done through imaging or recalling similar emotional experiences. The lastly is “genuine acting” mechanism which occurs when employees’ felt emotions are congruent with expressed emotion and display rules. A refinement in the study of emotional labour emerged when Brotheridge and Grandey (2002) introduced the distinction between job-focused emotional labour and employee-focused emotional labour. Job-focused emotional labour referred to the perceived level of emotional requirements in an occupation whereas employee-focused emotional labour is a process of managing emotions and expressions. Although the latter process was similar to the emotional labour process of Hochschild’s but the job-focused emotional labour captured something new. The more objective perspective that is represented by the concept job-focused emotional labour was also taken by Zapf et al. (1999) who introduced the term emotion work. Zapf et al.’s research group defined emotion work as the emotional requirements of a job, such as the requirement to express and handle negative emotions, the requirement to be sensitive to clients’ emotions, and the requirement to show sympathy.The teaching profession has been established as one that is profoundly emotional (Kinmann, Wray & Strange, 2011).Although there are many studies on teachers’ emotional labour but studies on emotional labour in amongst lecturers are limited. Lecturers undertake a disparate range of duties (for example teaching, research, administration, management and student counselling) with each requiring varying degrees of emotional display over an extended period (Ogbonna & Harris, 2004). There is an ever increasing job-specific role demands now being placed on university lecturers (Berry & Cassidy, 2014; Ogbonna & Harris, 2004). Reports (Asthana, 2008; UCU, 2008) have also highlighted how university lecturers are struggling to cope with the practicalities of rising student numbers and increased administration duties. In addition, factors such diversification of modes of delivery; restructuring and mergers resulting in high job insecurity; increased demands for efficiency and accountability; increased commercialization; reductions in funding; and the move towards financial self-reliance for institutions have caused a rise in the stress levels amongst UK universities (Berry & Gibbs, 2013; Kinmann, 2008).The studies on emotional labour in higher education in the Malaysian context is limited, hence this study is conducted to fill the gap in literature. Moreover, the previous study had a limitation in sample size and subjected to one university that is government funded. Though there are previous studies done on higher education and emotional labour but none addressing the impact of commodification of education and its impact to emotional labour. Therefore this study has been taken up to fill this gap in literature. Basically this study will test how does the three main consequences of commodification which are students as customers, reduced autonomy of lecturers and the increased and diverse workload impact emotional labour amongst lecturers.

3. Research Methodology

- The study measures the relationship between effects of commodification of education on emotional labour amongst private university lecturers in Malaysia. The quantitative instrument was developed based on previous scholars’ questionnaire. Simple random sampling methods was adopted and self-administered questionnaire was distributed by mail to lecturers in private university as a pilot study. The questionnaire consists of 3 sections, which are section A, B and C. Section A contains questions related to Emotional Labour dimension, Section B consists questions associated to commodification of education whereas section C contains of questions on demographic of the respondents. For each item a corresponding Likert scale anchored at 1 for “Strongly Disagree” and 5 “Strongly Agree” were used.

4. Findings

- The respondents who participated in the study, 41.7% of them were males while the remaining were 58.3% females. There were 50% of respondents of age between 30-39, followed by 40% of age 40 – 49 and 10 % of age 50 -59 55% of respondents had Bachelor Degrees, 24% with Master Degrees and 21% PhD holders. In terms of work experience, there were 41.7 % respondents with 1-5 years’ experience, 30.7 % with 6- 10 years’ experience, 21.6 % of 11-15 years and 6% of 16-20 years.One of the major aims of the study was to establish the existence of emotional labour amongst private university lecturers in Malaysia. The findings revealed that there is a high level of emotional labour prevalent amongst the lecturers. Almost all respondents agreed that they employed surface acting and deep acting during work either in class or during interaction with students. The results of the survey showed that the percentage of surface acting was higher than deep acting. 85 % of the respondent had admitted that they had faked their emotions when dealing with students and that the faking was induced by demands made by management to keep the customers happy. This proves the indication of exploitation of emotions in the workplace. In addition it was highlighted that faking was not a genuine intention by lecturers but due to pressures of complying with demands of management. This is supported by Constanti & Gibbs (2004) and Gaan (2012) that students and management of higher education institutions expect the academicians (lecturers) to perform emotional labour during the execution of their duties, thereby adding value to the teaching learning / teaching activity. As a service provider, the management is thus meeting the promise of delivering a hedonistic experience to the customer, while it is taken for granted that the academician will perform emotional labour in the classroom for the benefit of the students in the first instance, and consequently for the good of the university in the second (even via the potential for emotional deceit) (Constanti & Gibbs, 2004). Similarly majority of the respondents said that they change their actual feelings to please the students. This concurs with Gaan (2012) that they (students) know of the deceit but want to feel that they are different and enjoy the empathy of the teacher. This requires more than role-playing and can make the employees vulnerable and exploited by both the customer and the management.Lecturers’ evaluation by students is another significant feature of commodification of education. As consumers (students) of a service (education) have a right to evaluate or rate the service they receive. Based on the results, there was a strong positive correlation between the need to be friendly by lecturers and having good evaluations. Therefore it establishes the view that lecturers do have the stress of ensuring good evaluation or rating and they would have to behave in such way that would make their students feel good and happy. According to Lawrence & Sharma (2002) the lecturers evaluation form is also seen as a managerial tool intended as a disciplining power over academics, which is based on the market-based logic of student as consumers of educational product. It has potentially unfortunate consequences. Good teachers are the ones who please students. There is a tendency towards “edutainment”, providing students with a pleasant experience and high grades in return for their fees, rather than a challenging and uncomfortable learning experience. (Lawrence & Sharma, 2002)The results of the research also interestingly shows that the higher the position of the respondent such as head of departments, coordinators the lesser emotional labour. This could be due to the fact they have more autonomy compared to the others. Employees with high autonomy can decide when and how to respond to their demands. (Bakker & Demerouti; 2006). Similarly was the correlation between respondents’ academic qualification and emotional labour. It was seen that most of the respondents who had PhDs had experienced lesser emotional labour. We also find that age did not have significant factor that influenced the impact of emotional labour. Hence we can establish that emotional labour can be experienced by both younger and older respondents. Most lecturers also agree and that they suppressed their feelings when dealing with demands from management. This points to the fact that due to reduced autonomy, lecturers hesitate from speaking of how they genuinely felt at certain situations. This concurs with Wharton (1993) that employees who perform in low job autonomy or high job involvement are more at risk of emotional exhaustion than others who do not perform this activity. However the years of work experience of respondents did have a positive relationship to emotional labour. The higher the years of service, the less surface acting and more on deep acting. Lecturers also experienced emotional labour due to increased and diverse workload. This is in relations to dealing with conflicting demands from management and students. Most respondents stated that they used surface acting as a coping strategy. Many lecturers had stated that they had to sacrifice their professionalism in order to satisfy the management and keep the students happy in order to ensure students satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

- The results from the research clearly shows that consequences of commodification in the higher education sector does highly impact emotional labour amongst lecturers. According to the results we find that the lecturers use surface acting and suppression as a mechanism to cope with the emotional dissonance. Whilst we are unable to undo effects of commodification of education, we can mitigate the negative outcomes caused high emotional labour level by various intervention which should be made compulsory to maintain quality of education, employees’ satisfaction and the well-being of the lecturers. High emotional labour can be strongly associated with deterioration in service quality, high job turnover, absenteeism and low morale (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Maslach & Jackson, 1981) as well as decreased job satisfaction, performance, and well-being of employees (McCance et al., 2013). Moreover as stated by Berry & Cassidy (2013) management’s ignorance and apathy on the situation can be commercially threatening to the organization. From this research and other related studies, it becomes clear that lecturers are pressured to employ emotional labour to cope with pressures caused by commodification such as increased demands by students, eroding job autonomy and conflicting demands made by management. Organizations of higher education expect their teaching staff to perform in a manner that keeps the customers happy and maximize profit for the organization, without realizing that emotional labour is being employed. Therefore it becomes imperative for management of private universities to acknowledge the existence of emotional labour amongst lecturers and introduce interventions to alleviate negative emotional labour outcomes.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML