-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science

2016; 2(2): 33-39

doi:10.5923/j.jamss.20160202.01

Effectiveness of Exclusion in the Management of Student Behavior Problems in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya

Pamela Awuor Onyango1, Peter J. O. Aloka2, Pamela Raburu3

1Phd Student, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2HOD, Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

3Dean, School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter J. O. Aloka, HOD, Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

There have been attempts to address behavior problems among secondary stuudents in Kenya. However, very little success has been realized. The present study investigated the effectiveness exclusion in the management of student behavior problems in public secondary schools in Kenya. Assertive Discipline Model and Thorndike’s Behavior Modification theory informed the study. The concurrent triangulation design guided the study. The study population comprised 380 teachers from a total number of 40 schools that had 40 Heads of Guidance and Counseling (HOD), 40 Deputy Principals (DP) and 300 classroom teachers. The study employed stratified random sampling technique in the selection of teachers, Deputy Principals and Heads of Guidance and Counseling. A sample size of 28 Deputy Principals, 28 Heads of Guidance and Counseling and 196 teachers were involved in the study. Questionnaires, interview schedules and document analysis guides were used for data collection. Split half method was used to ascertain reliability and a reliability coefficient of 0.871 was reported. Face validity of the instruments was ensured by seeking expert judgment by university lecturers. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlational analysis while the qualitative data was analyzed using thematic framework. The study findings revealed that exclusion was effective in managing student behavior problems. The findings of this research may benefit the Ministry of Education of Kenya by providing current information on the effectiveness of exclusion, which may be used in managing student behavior problems.

Keywords: Effectiveness, Exclusion, Student, Behavior problems

Cite this paper: Pamela Awuor Onyango, Peter J. O. Aloka, Pamela Raburu, Effectiveness of Exclusion in the Management of Student Behavior Problems in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya, International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2016, pp. 33-39. doi: 10.5923/j.jamss.20160202.01.

1. Introduction

- Misconduct of students faced by schools has become more complicated and some researchers argue that student behavior problems need to be solved through corporal punishment while others do not think so (Mugabe and Maphosa, 2013). However, The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) stresses on the right of the child to protection of his or her human dignity and physical integrity; corporal punishment in institutions and families is considered as an act which goes against CRC (UNICEF, 2001). Similarly, the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) does not support the use of corporal punishment in schools, and instead recognizes the alternatives to corporal punishment which include prevention and intervention programs and strategies for changing student behavior (NASP, 2006). In Pakistan, corporal punishment has been in existence for 143 years, though in recent years there have been attempts to ban it (Iqbal, 2003).Similarly, the South African constitution opposes inhuman and cruel treatment (Cicognani, 2004). In South Africa, the government has taken several measures to implement the prohibition of corporal punishment in schools; a manual for teachers on alternatives to corporal punishment has been published and distributed widely. The prohibition of the use of corporal punishment on learners has become widely known in the school system (Soneson, 2005). Egypt has also banned corporal punishment even though its use can still be traced in schools and homes (Wasef, 2011). In Uganda, stakeholders have mixed feelings concerning the use of corporal punishment, and others argue that it should be used on the learners, while others feel it shouldn’t because it is not a corrective measure, but a coercive one. In protecting children from physical punishment, some stakeholders believe that laws should be implemented in order to avoid child abuse, while others do not support these laws (Damien, 2012).The current study was guided by Assertive Discipline Model by Lee and Marlene Canter (Canter and Canter, 2001) and Behavior Modification theory which was advanced by Thorndike (Corsine, 1987). Assertive Discipline theory has a five step discipline plan as consequences for breaking the rules, which is applicable to the present study. The student is first warned and then a ten minute time out is applied. Thirdly, 15 minute time out; fourth, the parents of the students are summoned. Lastly, the student is sent to the principal’s office (Canter and Canter, 2001). Thorndike’s Behavior Modification Theory (Rosenhan & Selignman, 1995) highlights human behavior in relation to the law of effect. According to the theory, learning is determined by events that take place after a given behavior, and learning is gradual but not insightful. Exclusion is such punishment as expulsion, suspension and in school suspension that involves the removal of students from the classroom (Welch and Payne, 2012). Mohrbutter (2011) in the USA indicated that suspension was used in the management of student behaviours. Bejarano (2014) in USA indicated that exclusionary methods removed children from significant opportunities of education that were bound to be of benefit to their future life. Additional findings established that exclusionary discipline was not fair and reasonable and disadvantaged some students. Zaccaro (2014) in America indicated that the use of seclusion and restraint had changed over time, resulting into injuries. Some respondents felt certain that these techniques were beneficial to individuals and are essential in solving crises. However, others argued that their physical and psychological harm was much more than any potential benefits they may have been having. It was also established that the absence of training and regulation standards of the procedures had likely led to inconsistent procedures in their application. Roache, Joel, Lewis & Ramon (2011) in Australia indicated that teachers who tended to use more inclusive management strategies like reward had students who were more responsible for their peers’ behaviours and their own behaviour. Another study by Ng (2015) in Toronto, Canada indicated that teacher reinforcement increased appropriate student behavior and decreased problem behavior. In addition, Agesa (2015) in Kenya indicated that manual punishment was effective for minor offences while suspension and exclusion were used for major indiscipline. The findings also indicated that suspension and exclusion were effective where there was massive destruction of property. Another different study by Kavula (2014) established that the use of alternative disciplinary methods by principals had no effect on students’ discipline. Kindiki (2015) in Kenya reported that students preferred the use of expulsion and suspension in managing students’ behaviour problem since they wanted behaviour problems to be kept out of school. In a separate study, Nakpodia (2012) in Nigeria reported that teachers found the classroom control difficult due to the absence of corporal punishment. The students engaged in misconduct most of the time because they knew the law did not allow the teachers to punish them through corporal punishment. Similarly, Sorrel (2013) in the USA indicated that teachers reported a decrease in time spent in managing student behaviour problems and decreased student misbehaviour. Students too became more engaged in academic work. In addition, teachers reported that there was significantly less disruptive behaviour in their classrooms. Another study by Khewu (2012) in South Africa established that time-out may only be effective if the cause of the problem was established before recommending a disciplinary measure. In Kenya, corporal punishment was banned in schools through Legal Notice No.56 of Kenya Gazette Supplement No.25:199 of 30th March, 2001 and the use of corporal punishment outlawed as a result of the Children Act, 2001 (Government of Kenya, 2001) which declared corporal punishment unconstitutional. The Ministry of Education as a result issued a directive to teachers to use methods other than corporal punishment that would control the widespread cases of indiscipline in the institutions of learning (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2005). Kiprop (2012) established that secondary schools in Kenya had developed unique ways of managing student behavior problems and the most common ones were manual punishment, guidance and counseling, exclusion and positive reinforcement (Agesa, 2015; Ndembu, 2013). Since the ban, school discipline has worsened and student behavior has become difficult to manage (Kindiki, 2015). Similarly, Kavula (2014) contends that the ban of corporal punishment in Kenya has not solved student discipline. Alawo (2011) too established that teachers face several challenges in the use of alternative corrective measures, a need for the present study hence, a knowledge gap which the study intended to fill on the effectiveness of exclusion in managing students’ behavior problems in secondary schools in Kenya.

2. Methodology

- The current study employed concurrent triangulation model in which both quantitative and qualitative data was collected. Target population for the current study consisted of 300 teachers, 40 deputy principals and 40 heads of guidance and counseling in public secondary schools in Bondo Subcounty of Kenya. Stratified random sampling technique was used to identify the schools and their proportions. Krejcie and Morgan (1970) sample size determination table was used to determine a sample size of 28 deputy principals, 28 heads of guidance and counseling and 196 teachers. Questionnaires were used to collect data from teachers, which enabled the researcher to obtain large amounts of information from a large sample of people (McLeod, 2014). The Effectiveness of Exclusion questionnaire and Management of Behaviour Problem Questionnaires adopted a 5 point likert scale: Strongly Agree, Agree, Undecided, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. Deputy Principals and Heads of Guidance and Counseling were involved in in-depth interview. The interview schedules allowed the researcher to obtain in-depth information that would not have been provided by the questionnaires (Oso & Onen, 2011). Document analysis guides were also used in gathering qualitative data. To ensure validity, the researcher developed the instruments with the help of expert judgment of two supervisors in the department of Psychology and Educational Foundations of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology. Piloting of the research instruments was done in 9 % of the total population that was not involved in the study. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlational analysis. Qualitative data from interviews was analyzed using Thematic Analysis, which followed the principles of thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (2006).

3. Findings and Discussion

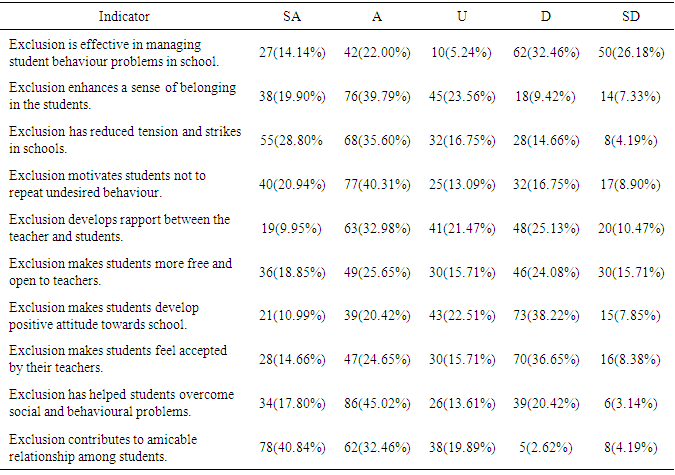

- A likert scale type of five options; strongly agree (SA), agree (A), undecided (U), disagree (D) and strongly disagree (SD) was used to investigate respondents opinion about the effectiveness of exclusion in managing student behaviour problems as ndicated on Table 1.

|

|

4. Conclusions

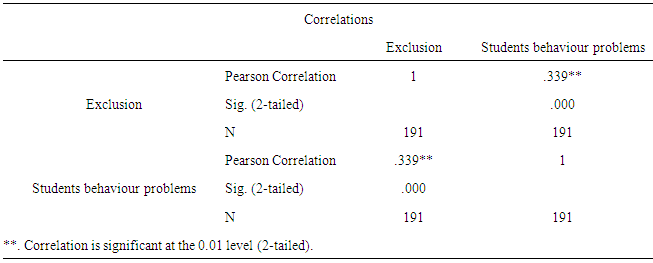

- The quantitative findings revealed that there was a positive relationship between exclusion and management of student behavior problems. Additional study findings too established that exclusion was effective in managing student behavior problems since it was more appropriate for major offences and had reduced tension and strikes in schools. Further findings established that exclusion enhanced a sense of belonging in the students and developed rapport between the teacher and students. However, other respondents argued that exclusion stigmatized the learners, consumed time, increased resistance among learners and led to school dropout. Based on the study findings, teachers should be provided with capacity building concerning the most appropriate way of applying exclusion as an alternative corrective measure in the management of student behavior problems.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML