-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2023; 6(1): 12-26

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20230601.03

Received: Mar. 27, 2023; Accepted: Apr. 10, 2023; Published: Apr. 15, 2023

A Randomized Trial on Investigating the Effectiveness of Pay-It-Forward Teaching as One Type of Voluntary Teaching, Assigned as a Complementary Project in an Upper-Intermediate Class, on Students’ Language Proficiency and Their Attitudes Toward Voluntary Teaching

Negin Rezghi

Department of Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, England, United Kingdom

Correspondence to: Negin Rezghi, Department of Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, England, United Kingdom.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In English teaching area, there has always been a debate on how to equip L2 English learners with adequate language skills to involve in fruitful discourse through English. Service-learning has been under exploration as a way to associate language use in-the-wild and in the classroom. Nevertheless, more investigation was needed to determine how to incorporate service-learning in the curriculum. One form of service-learning is voluntary teaching. The rationale for the present randomized trial is to investigate the effectiveness of a pay-it-forward teaching as one type of voluntary teaching, assigned as a complementary project in an upper-intermediate class, on students’ language proficiency and their attitudes towards voluntary teaching. The total number of 73 participants took part in this study, including 38 people (30 females and 8 males) in the intervention group and 33 (23 females and 12 males) in the control group. Nonetheless, two participants in the control group did not complete their second language test. The outcomes of various assessment tools employed by this study indicated that the pay-it-forward teaching project could have positive impact on participants’ language proficiency, confidence, and self-esteem while communicating in English outside the classroom.

Keywords: Learning In-situ, Voluntary teaching, Pay-it-forward teaching, Online realm, Attitude towards learning, English proficiency

Cite this paper: Negin Rezghi, A Randomized Trial on Investigating the Effectiveness of Pay-It-Forward Teaching as One Type of Voluntary Teaching, Assigned as a Complementary Project in an Upper-Intermediate Class, on Students’ Language Proficiency and Their Attitudes Toward Voluntary Teaching, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2023, pp. 12-26. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20230601.03.

Article Outline

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- "Special thanks to Dr. Hamish Chalmers for proofreading the article. "

1. Introduction

- Service-Learning – Can It Be a Pedagogical Task to Be Included in the Curriculum or Not?Nowadays, most Iranians of various ages are learning English at a fast pace. This is occurring mostly due to English being the international language and the pop culture of the world. In addition, given the abrupt advancement of technology in the current era and the fact that everyone can easily access cutting-edge technological devices, including cell-phones, tablets, and lap-tops, increasing number of students are willing to learn English as a lingua franca to be able to use technological devices more efficiently. Hence, L2 English learners have a variety of avenues to pick to learn and consolidate their command of English. However, a remarkable number of L2 English learners are unable to use their language knowledge in communication (Zarrabi and Brown, 2015). It appears that the classroom tasks do not suffice to provide a real-life simulation to implement their English in practice. Service-learning is a term that was proposed in the late 1900s, when Maryland schools (1988 - 1989) included community service as perquisites for passing academic courses. Yet, a definition of service-learning as transferring content knowledge to someone was not favorable for a number of researchers (e.g. Sigmon, 1979) as they called it a utopian vision and found it impractical. Nonetheless, the argument about whether to incorporate service-learning in pedagogy remained under debate.The research reported in this article is my attempt to begin to address service-learning, from earlier times until the time it was initially incorporated into pedagogy. The aim of the present study is to explore the effects on English language proficiency and learning satisfaction among upper intermediate adult learners of English in Iran. The following chapter describes the structure of my study and the steps I took to pursue my general aim.

2. Literature Review

- IntroductionThe review of literature first focuses on the argument between language use ‘in-the-wild’ and in the classroom. Moreover, service-learning as a recommended way to contextualize language use with the purpose of accelerating and facilitating language learning will be scrutinized. And finally, more recent modifications of service-learning; for example, Task-Based Language Learning, will be studied to make connections between former research and the present study. The Connection Between Classroom-Based Language Learning and Language Use “in-the-wild” The theory of Conversation Analytic Research on Second Language Acquisition (CA-SLA) asserts that language learning intrinsically involves active, occasioned, and embodied participation in social activities (see Gardner and Wagner, 2004; Eskildsen and Wagner, 2013, 2015). Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh (2019) is a recent study conducted on the teachers, in collaboration with the researchers, designing out-of-classroom activities for students. These activities involved participating in service encounters in a local network of businesses as a project. Over the course of the project, students video recorded their conversations and shared their experiences in the classroom afterwards. The benefit of this study was that students did not merely focus on the linguistic aspect of the tasks, but rather on the way that it was used in an interactional context and raised learner autonomy since the main data for the study are derived from students’ self-assessment of their own experiences. It would also benefit the validity of the findings if the researchers incorporated quantitative data by employing some language tests prior to and post-intervention. Moreover, the context was specific to the business realm, and students were even preparing for the interactions before accomplishing the project, which could have caused students’ interactions in-the-wild to be more like pre-prepared interactions rather than on the spot. But the present study, the focal point is to contribute to learning in situ, according to which, learning is a process whereby people make sense to knowledge by putting their knowledge into practice (Waite and Pratt, 2015). Rashid and Asghar (2016) is another study that strived to investigate the relationship between the technology usage of students as a way to enhance self-directed learning (SDL) and their attitudes towards learning and their academic performance. The sample was quite large, comprising of 761 female undergraduate students. Most of the participants were moderately using technology (M = 5.72, SD = 1.58). A Questionnaire consisting of separate sections regarding the media and technology usage scale (MTUAS, Rosen et al., 2013), self-directed learning (SRSSDL, William, 2007), as well as Utrecht’s work engagement scale (UWES-S, Schaufeli et al., 2006) was employed. The results illustrated that technology use was positively correlated with self-direction, students’ engagement, and their sense of achievement (p < 0.01). Therefore, Rashid and Asghar (2016) concluded that certain types of technology use (for example, email or useful contexts in social media) can be helpful for students’ academic achievement. As for the present research project, technology use is of high importance as the classes are all virtual due to the Corona virus pandemic, which coincided with the time scale for the research, and email and learning management system (LMS) are the mediums that are mostly being used by all students, and according to Rashid and Asghar (2016), is a proper approach to keep track of students’ work and make sure they are adequately engaged with the intervention over the semesters. Service-Learning in Online RealmA number of studies acknowledged that service-learning and the online classroom can be mutually beneficial; for example, Waldner et al. (2010) asserted that over the last decade, students are increasingly pursuing their education online. They defined e-service-learning (electronic service-learning) as “the instructional component, the service component, or both are conducted online” (p 3). However, service-eLearning has also been characterized as “an integrative pedagogy that engages learners through technology in civic inquiry, service, reflection and action” (Dailey-Hebert et al. 2008, p 1). The majority of studies that have been conducted in this area investigated one of the characterizations of service-learning, e-service-learning, or service-eLearning. The current study seeks to explore a type of service-learning which is a mix of all three definitions; it is conducted in an online instructional context, and yet through a service component that students could accomplish either online or in-person depending on which approach they find more convenient for themselves. Below, other approaches to explore service-learning in various educational systems will be explored, which made it possible to design and employ different classroom tasks with relevance to community services.The Appearance of Service-Learning through Task-Based Language Learning (TBLT) and Community Service-Learning (CSL) in EducationAccording to Harmer (2001), Task-Based Language Learning (TBLT) was popularized by Prabhu (1987) while working in Bangalore, India. Prabhu (1987) placed emphasis on assigning tasks that have clearly-defined non-linguistic outcomes. Nevertheless, there would still be a debate on whether such tasks can help to develop students’ language proficiency. With regards to attitudes towards service-learning, some recent studies affirmed that sense of achievement and motivation are highly correlated (e.g. Han and Lu, 2018).Han and Lu (2018) focused on the influence of achievement motivation and goal setting on learners' strategy use in language learning. The researchers built on Lee et al.’s (1989) goal setting theory, that is, a goal is seen as the engine to fire the action and also functions as a direction that learners can act upon and achieve success. The sample consisted of 230 third-year university students, 83 males and 110 females, and were all from non-English majors.Three questionnaires were used, including Achievement Motivation Scale (AMS) of Gjesme and Nygaard (1994), a self-made goal-setting scale, and Oxford’s (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). Also, a Chinese version of AMS was employed to refer specifically to an English learning context. The results illustrated that achievement motivation was highly correlated with communication strategies, including social, affective, cognitive, and metacognitive strategies. Drawing upon these findings, the present study also provides an intervention which will require students to apply a number of the aforementioned learning strategies. Yet, the current research seeks to explore the effects of the intervention on students’ attitudes towards voluntary works to become active members of society, not merely their motivation for self-development.

3. Methodology

- IntroductionIn this chapter, I state the aims and objectives of the study, articulate the research questions addressed, and outline the methodology used to explore them. Finally, I outline ethical considerations about the operation of the research.AimThe overall aim of this study is to investigate the impact of pay-it-forward teaching as one type of voluntary teaching on students’:• English proficiency• self-satisfaction as a result of learning success • motivation for English learning, and future plans for contributing to community-building works, e.g. through voluntary teaching Research Questions This project adopted a parallel group randomized trial design to address the following questions: RQ1: Does pay-it-forward teaching as a form of voluntary teaching affect students’ English proficiency?RQ2: Does helping another person with language learning affect students’ attitudes towards voluntary projects, like cooperating with global NGOs’ skill-based projects from home? RQ3: What are students’ more in-depth self-perceptions of the impact of pay-it-forward teaching on their language proficiency and attitudes towards voluntary works through English?HypothesesThe Null Hypothesis (HO) Providing the intervention to participants makes no difference in their English language proficiency and attitudes towards voluntary teaching.Alternative Hypotheses: Hypothesis 1(H1) & Hypothesis 2 (H2):H1: The intervention is associated with changes in participants’ English language proficiency.H2: The intervention has mediating effects on students’ attitudes towards voluntary teaching. Research DesignResearch methods are specific procedures for collecting and analyzing data. For this study, I have incorporated data in the form of words and numbers, i.e., both quantitative and qualitative data, to address the research questions. Accordingly, overall language tests on all units of Touchstone 4 book were provided for students on the platform of https://lms.safirmazandaran.com/. Also, I have made use of questionnaires pre- and post-intervention to assess of students’ attitudes towards voluntary teaching, and focus groups to delve into students’ progress in the pay-it-forward teaching project as one type of voluntary teaching. Students were asked to complete the pre-intervention questionnaire and the first language test at the beginning of the semester. Towards the end of the semester, students had to accomplish the post-intervention questionnaire and the second language test on the same platform.To address RQ1 and RQ2, this project adopted a parallel group randomized trial design, with a 1:1 allocation ratio at the level of the individual participant. A randomized control trial (RCT) is a form of scientific experiment to assess whether a cause and effect relationship exists between an intervention and an outcome (Sibbald and Roland, 1998) and is used to evaluate the relative effects of alternative social and educational interventions (Mosteller and Boruch, 2002). Also, Hutchison and Styles (2010) declared that according to the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), a randomized trial “should be considered as the first choice to establish whether an intervention works” (p 7). Furthermore, the Cabinet Office Behavioral Insights Team asserted this method to be the best way to investigate whether a policy is working or not (Haynes et al., 2012). In the context of my study, an RCT can achieve sufficient control over the confounding factors (e.g. age and gender) to deliver a useful comparison of the intervention under investigation. Random allocation to comparison groups ensures that any differences in average characteristics between the groups at baseline are chance differences and not systematic differences. That is, comparison groups are unbiased approximations of each other. As for the present study, the participants are different with respect to age and gender factors. Plus, the number of female and male participants varies to a great extent (details on participants will be provided in the next section). Furthermore, individual differences may result in some participants accomplishing the intervention diligently while others carrying it out less attentively. These differences can influence the study outcomes. But random allocation results in groups with similar characteristics and enables statistical control over these influences, and as acknowledged by Torgerson and Torgerson (2008) “is the best approach to dealing with and controlling for selection bias, regression to the mean and temporal changes” (p 22). Furthermore, to address RQ3, I used a focus group design. Focus groups can contribute to the already known knowledge around a specific area and can be used as a stand-alone method or as part of a mixed methods study, that is, a study including both qualitative and quantitative methods (Doody et al., 2013a; Then, 2000). In the context of my study, it is beneficial as it allows direct, intensive contact with individuals to provide more in-depth data, which enriches the quantitative data of the study (Dilorio et al., 1994; Kingry et al., 1990; Then, 2000). Furthermore, focus groups welcome diversity of opinions (Byers and Wilcox, 1988) and exchange of perceptions that may challenge individual’s former opinions and encourage them to come to new understandings (Hillerbrandt, 1979; Krueger, 1994).

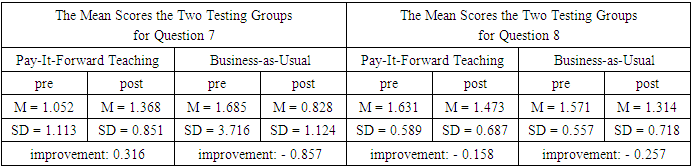

| Figure 3.1. CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram |

4. Results

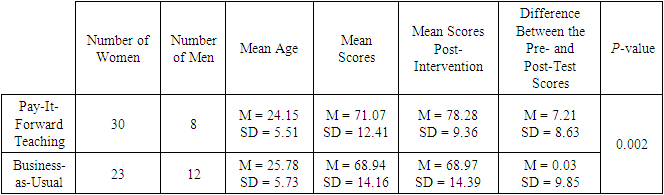

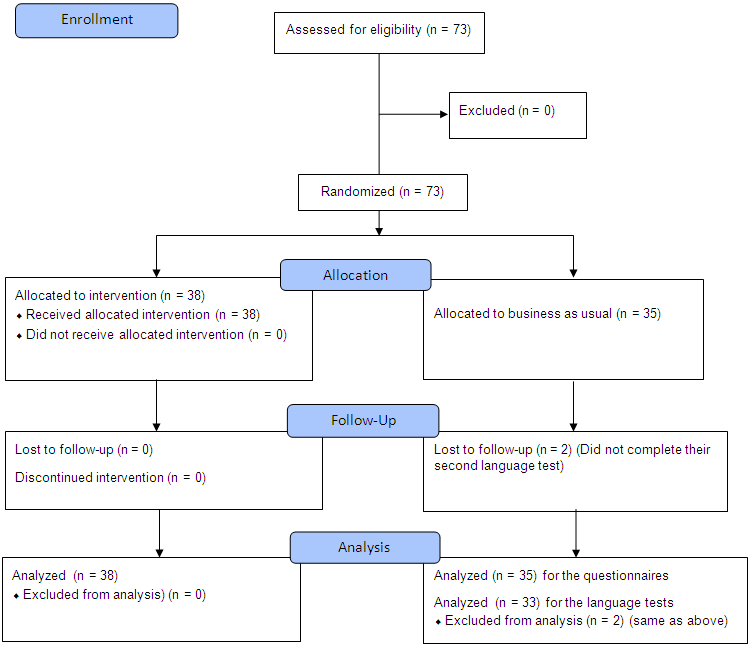

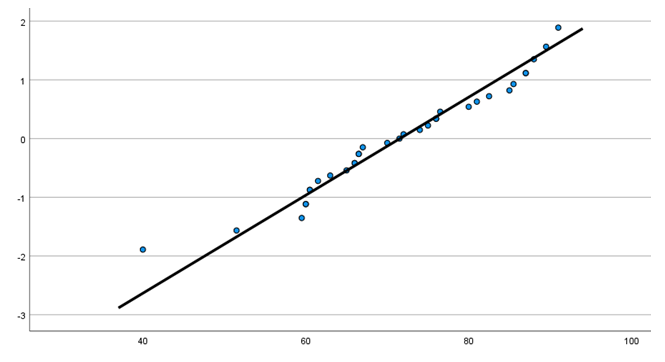

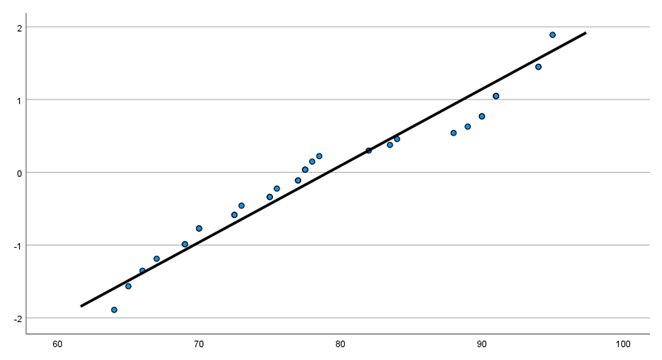

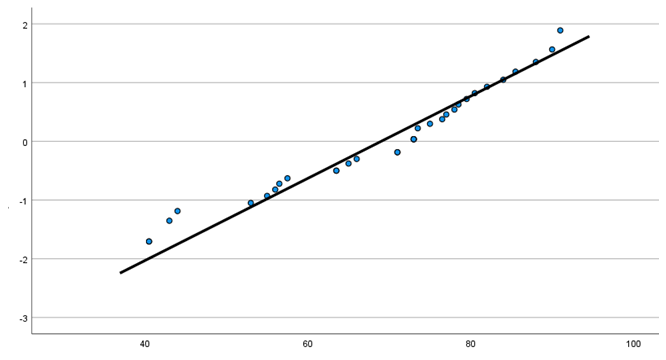

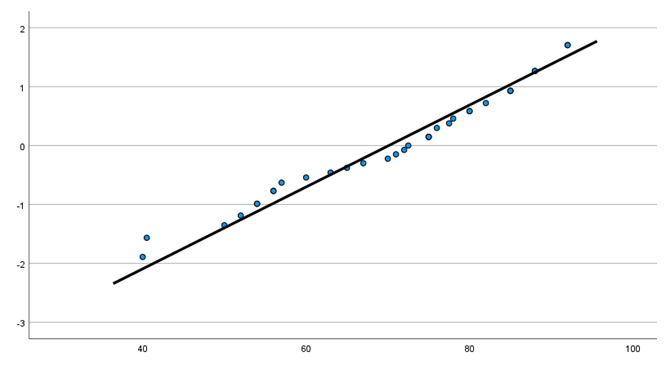

- IntroductionIn this chapter, I will present the results of the English language tests, pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, focus groups, and follow-up email correspondences.Descriptive StatisticsThe total number of participants was 73. They were aged between 18 and 36. There were 53 women and 20 men. Table 4.1 presents the breakdown of these characteristics by intervention group and the mean scores on the pre-intervention English test. Given the RCT design of the study, participants were tested for normal distribution in terms of their test scores, using IBM SPSS. Two participants in the business-as-usual group were lost to follow up and did not complete the post-test. These participants’ data were excluded from the analyses. For this reason, normal distribution of the pre- and post-intervention test scores were measured for 71 participants. Figures 4.1 – 4.4 indicate that the data from test scores were normally distributed as the points on the normal Q-Q plots fell approximately on the straight diagonal lines for both groups prior- and post-intervention.

| Figure 4.1. Normal Distribution of the Pay-It-Forward Teaching Group’s Prior-Intervention Language Test Scores |

| Figure 4.2. Normal Distribution of the Pay-It-Forward Teaching Group’s Post-Intervention Language Test Scores |

| Figure 4.3. Normal Distribution of the Business-as-Usual Group’s Prior-Intervention Language Test Scores |

| Figure 4.4. Normal Distribution of the Business-as-Usual Group’s Post-Intervention Language Test Scores |

|

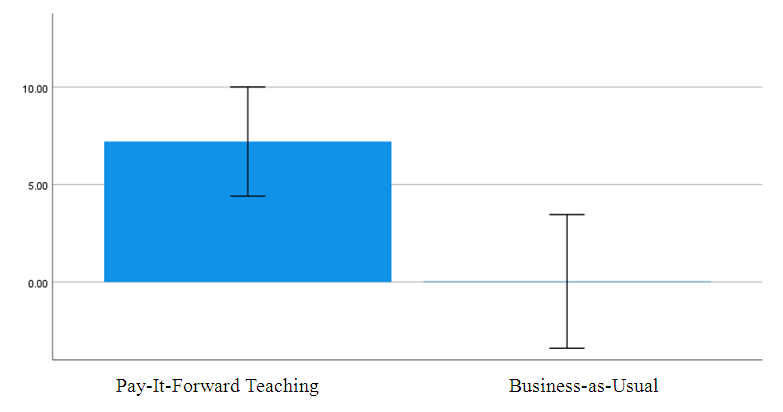

| Figure 4.5. The Comparison of the Difference in the Scores of the Pre- and Post-Intervention Language Tests Between the Two Groups |

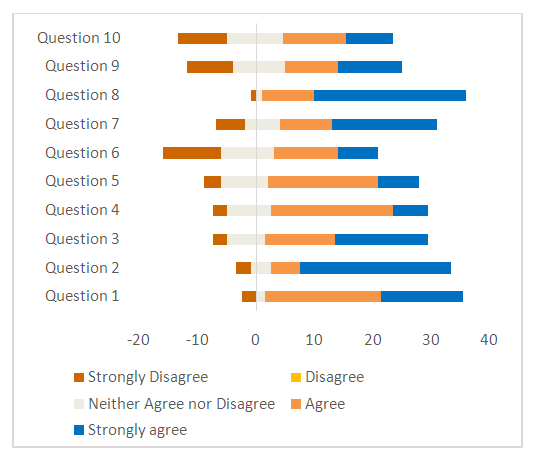

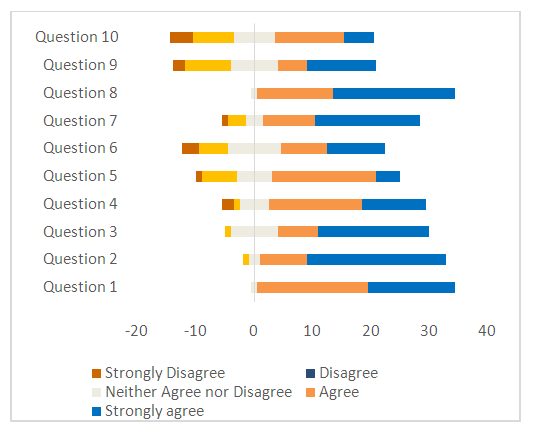

| Figure 4.6. Pay-It-Forward Teaching Group's Attitudes Towards Voluntary Teaching: Before the Intervention |

| Figure 4.7. Pay-It-Forward Teaching Group's Attitudes Towards Voluntary Teaching: After the Intervention |

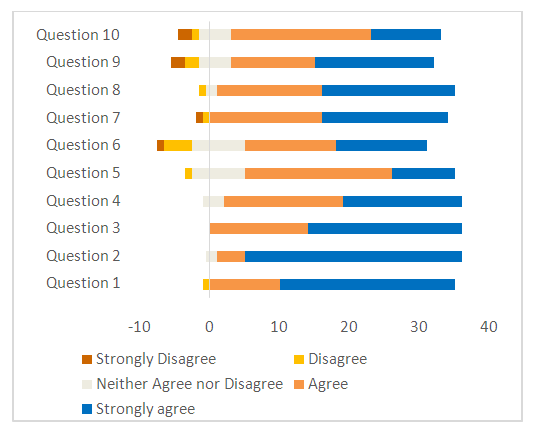

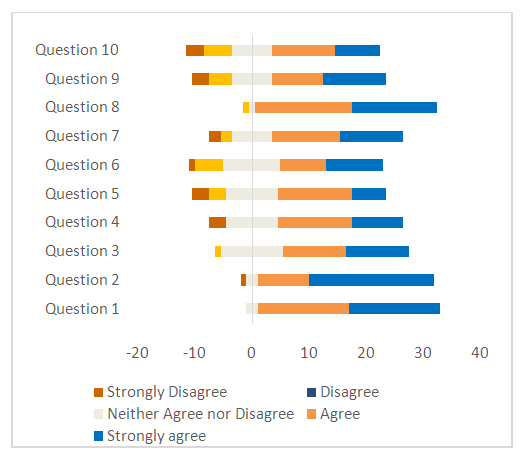

| Figure 4.8. Business-as-Usual Group's Attitudes Towards Voluntary Teaching: Before the Intervention |

| Figure 4.9. Business-as-Usual Group's Attitudes Towards Voluntary Teaching: After the Intervention |

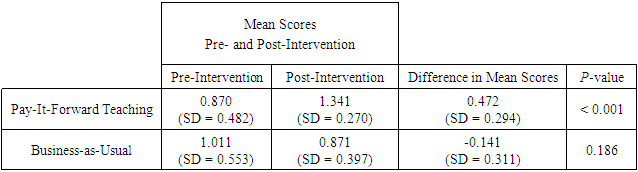

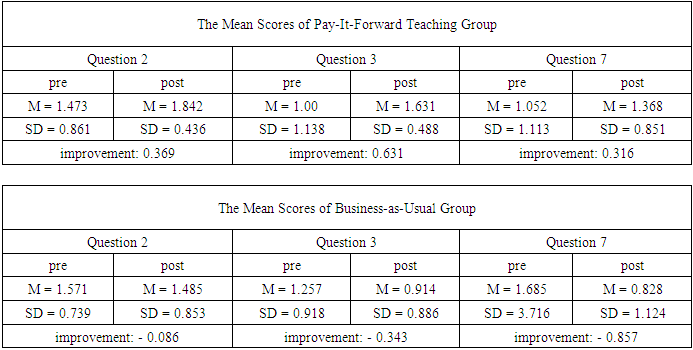

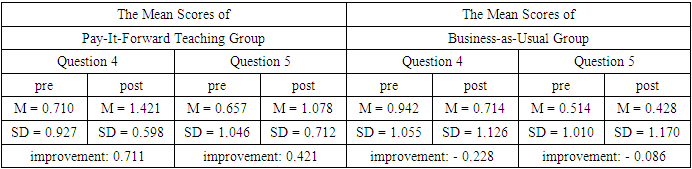

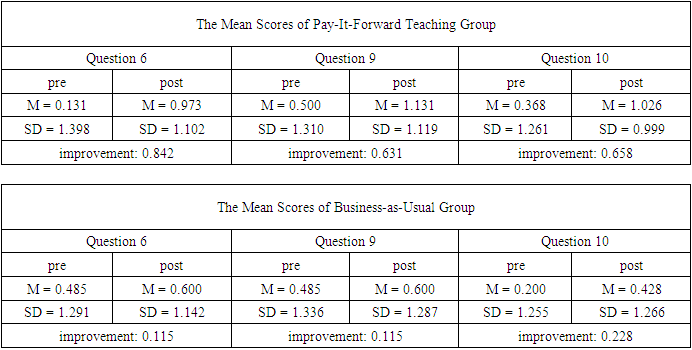

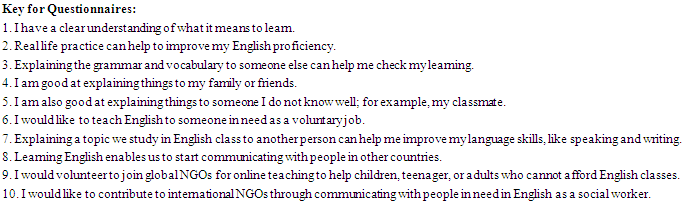

Figures 4.6 and 4.7 represent the responses of the pay-it-forward teaching group to the pre- and post-intervention attitudes questionnaire. Figures 4.8 and 4.9 illustrate the responses of the business-as-usual group. In the next sections, descriptive and comparative reports of the Figures will be provided.On the whole, the difference in mean score between the beginning and end of the semester for the pay-it-forward teaching group was statistically significantly different (p < 0.001). See table 4.2. The difference in mean score for the business-as-usual group was not statistically significantly different (p = 0.186). Hence, the pay-it-forward teaching intervention was responsible for the change in attitudes and we can conclude that engaging in pay-it-forward teaching as one kind of voluntary teaching improves attitudes towards voluntary teaching whereas not entering in voluntary teaching by a pay-it-forward teaching project has no detectable effect on attitudes. Below, more details of changes in attitudes in different questions will be discussed.

Figures 4.6 and 4.7 represent the responses of the pay-it-forward teaching group to the pre- and post-intervention attitudes questionnaire. Figures 4.8 and 4.9 illustrate the responses of the business-as-usual group. In the next sections, descriptive and comparative reports of the Figures will be provided.On the whole, the difference in mean score between the beginning and end of the semester for the pay-it-forward teaching group was statistically significantly different (p < 0.001). See table 4.2. The difference in mean score for the business-as-usual group was not statistically significantly different (p = 0.186). Hence, the pay-it-forward teaching intervention was responsible for the change in attitudes and we can conclude that engaging in pay-it-forward teaching as one kind of voluntary teaching improves attitudes towards voluntary teaching whereas not entering in voluntary teaching by a pay-it-forward teaching project has no detectable effect on attitudes. Below, more details of changes in attitudes in different questions will be discussed.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- IntroductionIn this chapter, I will review the context and aims of my investigation. Also, I will summarize the findings detailed above and relate them to the study’s research questions. The results will be assessed to determine whether they concur or differ from what the literature conveys about the topic of my dissertation. I will then elucidate what the current study’s findings add to our understanding of service-learning. And accordingly, will recommend the implications for future practice of language schools and academies, the wider science education community and possible areas for further research.Context and Aim: RevisitedThe catalyst for this investigation was my observation of classroom environments in which producing the target language was the only focal point. Indeed, students were apparently successful in meeting the objectives of each classroom sessions’ target language. But there was a common complaint among students, that is, how to use the language in conducting a real communicative context. Moreover, according to my own observations, students feel perplexed on what structures or words to employ when they are not instructed by the teacher, or the tasks do not address what target language is demanded to be used in a certain activity. Furthermore, former studies have found out that many EFL learners use English outside the classroom mainly for listening and reading but not for speaking because they are afraid of making mistakes and using the language incorrectly while speaking (e.g. Hyland, 2004; Barker, 2004). Hence, tasks were needed to help students gain better results (Waite, 2011) as well as involving students in real-life activities outside the classroom to expand the students’ learning environment (Guo, 2011). Hence, drawing upon the notion of language use in-the-wild proposed by Hutchins (1995), and considering the debate that still exited on how to associate classroom-based learning with social interactions outside the classroom (Blum-Kulka and Snow, 2004; Adams, 2019), the present study strived to employ pay-it-forward teaching as an approach to link between inside and outside classroom language use by having students use their English knowledge in a real-world practice. Students were provided with teaching materials but did not receive any training on how to teach the lessons.

6. Findings

- ProficiencyIn response to the first research question regarding the impact of pay-it-forward teaching project on students’ language proficiency, participants in the pay-it-forward teaching group proved to have made statistically significantly greater progress in their English proficiency compared with the business-as-usual group. Also, the intervention proved to have enhanced learners’ autonomy as it provoked students to not merely focus on the linguistic aspect of pay-it-forward teaching, but rather on the way that it was used in an interactional context (also see Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh, 2019). Unlike previous similar studies, this study incorporated both subjective and objective analyses to assess students’ progress during the study. Indeed, the language tests brought about quantitative data for numerical assessment, and students’ self-assessment as well as my own observations as a teacher added qualitative data to the study, which contributes to Sigmon’s (1979) plea for statistical for outcomes research related to service-learning. Also, students were not asked to prepare for their interactions outside classroom. Thus, the intervention did not just simulate in class lessons, but called for participants to use their English knowledge in real-life situations, that is, learning in situ (Waite and Pratt, 2015). This gave rise to authentic interactions between L2 English speakers (Speck and Hoppe, 2004; Song and Hill, 2007; Broadbent and Poon, 2015; Rashid and Asghar, 2016). A number of the participants in the pay-it-forward teaching group reported to have imitated the teacher while teaching vocabulary or grammatical structures. However, they were freely deciding how to present the lessons to someone else. Thus, the intervention did not merely simulate real-life practices, but it actually put students in a real-life situation to transfer their knowledge to another L2 English speaker. The intervention had an objective, that is, to stimulate participants to make their counterpart understood, but it was not directly mentioned by the researcher. Rather, participants themselves reached this goal as they subconsciously intended to be high-achievers while performing in front of another L2 English speaker. Thus, the current study was an initiative to create an authentic link between inside and outside classroom language use with no explicit instruction provided for participants on how to accomplish the project prior-intervention.AttitudesTo address the second and third research questions about students’ attitudes towards voluntary teaching and more in-depth self-perceptions of students on their progress during the intervention, the findings of pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, as well as focus groups and follow-up email correspondence suggested that all students believed that using English for the communicative practices involved with service-learning will improve their language proficiency. Also, a great deal of students, in the intervention and the control group, were in favor of either teaching to someone as a voluntary job or communicating with international L2 English speakers as a social worker. Little difference in attitudes towards these voluntary jobs was witnessed in the control group, whereas some intervention group members altered their opinion from negative to positive or very positive attitudes after doing the project, i.e., pay-it-forward teaching. Therefore, the act of engaging in pay-it-forward teaching appears to have an affirmative impact on students’ attitudes towards voluntary teaching as a service-learning task, as students began feeling empathy towards other human beings (Sleurs, 2008). Also, participants in the pay-it-forward teaching group started planning for their teaching sessions to imitate teacher’s techniques while teaching in classroom. In this way, they strived to take the best advantage of their language skills so that they could run successful teaching sessions. In other words, participants enhanced their systems-thinking competence, referred to as a central component to achieve sustainability in literacy (Croften, 2000; De Haan, 2006; Sterling and Thomas, 2006; Sipos et al., 2008; Sleurs, 2008). Additionally, participants became more confident about their knowledge, worried less while communicating with someone in English, and improved their own language skills as a result of being bound to review the lessons before their teaching sessions. The research findings are also in alignment with Conversation Analytic Research on Second Language Acquisition (CA-SLA) approach, embracing both verbal and non-verbal conduct, in real-life practices to reinforce social interaction (see Gardner and Wagner, 2004; Eskildsen and Wagner, 2013, 2015).Implications for Future PracticeThis study involved participants of 18 - 35 year-olds. Despite being occupied with many other responsibilities, most participants in the intervention group were absolutely engaged with the project and sent their reports regularly. According to Dornyei’s (2005) research on Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), motivation is defined as a fluctuating attribute; it may evolve over the course of learning. Furthermore, Ellis (1997) mentioned that motivation is not merely related to success in SLA, defined as aptitude. Rather, it involves factors that affect the degree of efforts the learner would make in L2 acquisition. Indeed, motivation in higher levels, leads to learners’ conscious involvement in different learning strategies, including “selective attention” or “questioning for clarification,” which potentially lasts in learners’ eventual success (Ellis, 1997: 77). The pay-it-forward teaching project also required conscious involvement of participants and considering the success of the intervention group in their language tests as well as Ellis (1997) and Dornyei (2005)’s assertions, we can conclude that pay-it-forward teaching could enhance students’ motivation towards learning. The time-consuming issue with Community Service Learning (CSL), which remained under debate as to how service-learning can be consolidated in the curriculum, was also responded to by the current study. The present study calls for collaboration of Community Service Learning (CSL) and Task-Based Learning (TBL) through integration of some of their features. In other words, it sought to design and employ a task to foster processes of negotiation and modification of the target language (Richards and Rodgers, 2001), as well as enabling participants to critically reflect on their work outside the classroom (Whitaker and Berner, 2004; Barry, 2015).In addition, according to Dewey’s (1971) theory, engaging in service-learning can help to foster problem-solving ability in students to be engrossed in societal issues and find practical solutions as full-functioning members of society (see Speck and Hoppe, 2004). When service-learning is performed in the form of pay-it-forward teaching –whether it be online or in-person– this study suggests that it can produce twofold advantages; first, service-learning as a way of transferring knowledge would accelerate and facilitate students’ learning. Second, pay-it-forward teaching encourages students to use technology like email or useful contexts in social media, which has formerly proved to be helpful for students’ academic achievement (Rashid and Asghar, 2016) and was also witnessed by the current study’s focus groups’ findings. Additionally, conforming to socio-cultural theory, the present research aims to make learners to construct knowledge in collaborative activities through dialectic interaction. Task-type is also important to provide learners with varied opportunities to produce modified output (Pica et al., 1989; Swain and Lapkin, 1998; Swain 2000).With respect to the effect of pay-it-forward teaching on language proficiency, the results of test scores indicated significant differences between the two experimental groups. Thus, the null hypothesis is rejected and the experimental hypothesis retained. It appears that teaching English to someone else can improve students’ own language proficiency. Consequently, the pedagogical implications of this study are to recommend that teachers in similar situations to the one in which this study was conducted consider making pay-it-forward teaching part of their curriculum.According to students’ reports in email correspondence and in the focus groups, during the teaching sessions, they interacted with their partners quite productively as they started negotiating the lessons and shared their knowledge of the language skills. Relatedly, the participants in the pay-it-forward teaching group reported that they could also solve their own misunderstandings of classroom lessons when they attempted to explain the lessons to someone else. Moreover, in countries like Iran where English is considered as a business language, L2 English learners have little chance of applying their English knowledge in business communication. Relatedly, many students complain that they are not learning English properly or are not sure about their language proficiency. The pay-it-forward teaching project intermingled target tasks and pedagogical tasks, defined by Nunan (2004), which can help to do something outside the classroom and in the real world, but with linguistic outcomes and by usage of the target language learned in the classroom. With respect to the goal setting theory, that is, a goal is seen as the engine to fire the action (Lee et al., 1989), having authentic tasks on their own does not appear to suffice. Rather, they have to include specified objectives and be perfectly structured to bring about the desired outcomes. A pay-it-forward teaching project, as defined and elaborated by this study, can boost students’ morale by encouraging them to perform as spirited and assiduous members of society. Students are required to put their theoretical knowledge into practice so that they can assure that they are adequately competent to help to enhance the world’s increasing knowledge.

7. Conclusions

- This study strived to investigate the impact of pay-it-forward teaching on students’ language proficiency based on objective analysis of quantitative data from language tests, as well as students’ attitudes towards voluntary teaching through the subjective assessments of students and me (as the teacher and the researcher). The study benefited from various research instruments, consisting of pre- and post-tests for language proficiency, prior- and post-intervention questionnaires, focus groups, and email-correspondence. The results of the proficiency test indicated that students in the intervention group improved to a statistically significantly greater extent than the control group. Furthermore, the intervention group began thinking highly of pay-it-forward teaching after accomplishing it. But the control group’s impressions did not change remarkably.Nonetheless, with regards to Dornyei’s (2005) definition of motivation as a fluctuating attribute, perhaps the results of the present research could vary if it was conducted on a different age group. Hence, it would be beneficial if future studies to conduct the same intervention on younger (teenagers) or older learners (middle-aged learners) at upper-intermediate level to investigate whether individual differences between younger and older learners could also be an effective factor on the success of the pay-it-forward teaching project.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML