-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2018; 4(3): 49-58

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20180403.01

The Impact of Teaching Pragmatic Functions to High School Learners

Tooran Arghashi1, Bahman Gorjian2

1Department of English, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

2Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of pragmatic functions instruction on Iranian high school EFL learners' writing proficiency. For the purpose of this study, 60 female Iranian learners studying at the first grade of high school in Dezfool were selected through simple random sampling procedure. The results of the proficiency test revealed that the groups were homogeneous. Then they were divided into experimental and control groups. The control group was taught based on usual and traditional methods of writing instruction and the experimental group received treatment based on pragmatic function instruction in writing one-paragraph essays. The achievement of writing on pragmatic functions was assessed based on a pre and post-test method. Pre-test included 30 items, focusing on pragmatic functions proposed by Halliday (1985). The pre-test was performed before the treatment period to make the researcher sure that the groups are homogeneous on pragmatic function knowledge in writing essays. During the treatment, the students wrote samples on the specified pragmatic functions in each weekly task. Having done the treatment, the researcher administered the post-test on pragmatic functions consisting of 30 multiple-choice items related to pragmatic functions acquired during the treatment. Then, the results revealed that there was a significant difference between the mean scores of the participants in the control and experimental groups (p<0.05). Thus, the students who received explicit pragmatics instruction focusing on language pragmatic functions in writing essay performed better on the post-test than those who did not. This empirical study has provided insights into learners' pragmatics knowledge in writing effective essays.

Keywords: Pragmatic functions, High school EFL learners, Writing proficiency

Cite this paper: Tooran Arghashi, Bahman Gorjian, The Impact of Teaching Pragmatic Functions to High School Learners, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2018, pp. 49-58. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20180403.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pragmatic functions writing in conversations with the completion test format in a second language does not enjoy a big amount of support. Second language writers need to reach a specific level of fluency by the time they are writing pragmatic functions (Chenoweth & Hayes, 2001). Otherwise, they will find it a very effortful process that may require conscious attention to retrieve words and spelling; leaving little working memory free to attend to higher-level concerns such as generating detailed content and organizing the discourse (Chenoweth & Hayes, 2001).According to Brock and Nagasaka (2005), there are a number of language competencies that English language learners must develop, in tandem, in order to communicate successfully in English. Any successful communicative event, at least one that extends beyond expressions of simple, immediate need, will require that L2 speakers have developed some mastery of syntax, morphology, phonology and lexis of the English language. Yet, as many English teachers recognize, pragmatic functions that are grammatically and phonologically correct sometimes fail because the learners' pragmatic competence-his or her ability to express or interpret communicative functions in particular communicative contexts-is undeveloped or faulty. Pragmatic incompetence in the L2, resulting in the use of inappropriate expressions or inaccurate interpretations resulting in unsuccessful communicative events. This may make some misunderstandings for native speakers that the L2 speaker is either impolite or ignorant. Learners should do many writings dealing with many particular elements of the writing skill that time spent writing fulfills efficient practice for improving them. Learners should transfer a message while writing. Most writing should be done with the aim of communicating a message to the reader and the writer should have a reader in mind when writing. Writing instruction should be based on a careful needs analysis which considers what the learners need to be able to do with writings. Learners should bring experience and knowledge to their writing. Writing is most likely to be successful and meaningful for the learners if they are well prepared for what they are going to write (Nation, 2008). Teaching pragmatic functions in the language classroom is important for two reasons: (1) it has been demonstrated that there is a need for it to communicate properly; and (2) quite simply, it has proven to be effective in negotiation of meaning. Bardovi-Harlig (2001) asserts that, without instruction, differences in pragmatics show up in the English of learners regardless of their first language background or language proficiency. As the research into pragmatic functions across cultures has demonstrated, pragmatic transfer between languages can, on occasion, make non-native speakers appear rude or insincere. Tateyama, Kasper, Mui, Tay, and Thananart (1997) demonstrate that pragmatic routines are teachable even to beginning foreign language learners. Teaching target norms, which learners are then forced to use, does not seem to be an appropriate way to teach pragmatics, as learners' pragmatic choices are connected with their cultural identities. In her list of the goals that instruction in pragmatics should aim for, Kasper (1997) points out that second language learners do not merely model native speakers who create both a new inter-language and an accompanying identity in the learning process. Kasper further comments that successful communication is a matter of optimal rather than total convergence for each learner, it is important to give them the opportunity in the classroom to reflect on their own linguistic choices, compare those choices with pragmatic features of the target language and then to try out the various other options available to them.One approach that may help learners create their own inter-language is awareness raising. Rose (1994) introduces active video-viewing activities and suggests that this approach, which promotes pragmatic consciousness-raising (PCR), has the distinct advantage of providing learners with a foundation in some of the central aspects of the role of pragmatics, and that it can be used by teachers of both native speakers and non-native speakers. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of instruction on the acquisition of pragmatic competence in the situation of EFL written production among young learners at high school level, to analyze the effect of CR on pragmatic functions in their production and to attain some insights into teaching communicative strategies in EFL writing.In order to be successful in communication, it is essential for second language learners to know not just grammar and text organization but also pragmatic aspects of writing skill (Bachman, 2009). "Pragmatic competence" can be specifically defined by Kasper (1997) as knowledge of applying language communicatively and appropriately in relation to the context. Previous studies in inter-language pragmatics have shown that differences and similarities exist in how to carry out communicative actions between writing skill learners and native speakers of target languages. In many EFL classes, even where teachers have devoted much time to teach using pragmatic functions in writing essays. The results have been disappointing, especially where English is not the main medium of communication. Therefore, finding a new method to solve this problem and help teachers with writing instruction on pragmatic functions seems to be crucial. This study tries to fill this gap, thus the present study investigated the effect of pragmatics functions instruction and CR on learning pragmatic functions and their impact on developing writing proficiency among EFL learners.

2. Literature Review

- The term of "pragmatics" is defined in different ways and from different perspectives. Morris (1938) initially defined pragmatics as "the field related to the relations of signs to the interpreters, whereas semantics deals with the relations of signs to the objects". He applied the term pragmatics in a broad sense to refer to "the study of the relation of signs to interpreters", whereas he defined syntax as "the formal relation of signs to one another" and semantics as "the relation of signs to the objects to which the signs are applicable" (Morris, 1938, p. 6). According to Morris's (1938) definition, pragmatics covers not only linguistic pragmatics but also comprehending intentional meaning (Yule, 1996). Therefore, Morris's definition is based on a semiotic view of pragmatics compared with various definitions of linguistic pragmatics (Schauer, 2009). In relation to the second group, the language learners were assessed about the comprehension of meanings of linguistic utterances that are culture-specific. Pragmatics focuses on the way of using the context by speakers and writers to convey intended meaning of phrases. In other words, "it concentrates on those aspects of meaning that cannot be predicted by linguistic knowledge alone and take into account knowledge about the physical and social world" (Peccei, 2000: 2). In addition, it is not sufficient for language learners to notice just too pragmatic features (Kasper & Rose, 2002), since many aspects of L2, pragmatics either is not learned or learned very slowly (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). Therefore, it is necessary for learners to focus on L2 cultural features (Kasper & Rose, 2002).Another definition of pragmatics was proposed by Levinson (1983) who claims, "Pragmatics is the study of those relations between language and context that are grammaticalized, or encoded in the structure of a language" (p. 9). This definition confines pragmatics to the study of linguistic structures, that is, the study concerned simply with the relationship between language and context. He believed that contexts are culturally and linguistically dealt with interpretation and production of expressions relevant to language understanding (Levinson, 1983). In another argument, Thomas (1995) defines pragmatics as "meaning in interaction" (p.22). Consequently, context (both physical and conceptual) is an essential element in human interaction. In other words, in a similar definition, Kasper and Rose (2001) state that pragmatics is "the study of communicative action in its sociocultural context" (p. 2). Another definition of pragmatics proposed by Crystal (1985) that people's choice of sounds, grammatical construction, and vocabulary in social interactions is influenced by pragmatics (Crystal, 1985). Therefore, pragmatics consists of both context-dependent aspects of language structures and principles of language usage and comprehending, that deals nothing or little with linguistic structure (Levinson, 1983). That is, the study of pragmatics focuses on the relationship between language use and the real-world context in which it is used.

2.1. Pragmatic Competence

- Pragmatic competence is a significant component of communicative competence (Zheng & Huang, 2010). The notion of pragmatic competence was initially introduced by Chomsky (1980) as "the knowledge of conditions and manner of appropriate use (of the language), in conformity with various purpose" (p. 224). Therefore, this definition was considered opposite to grammatical competence defined by Chomsky as "the knowledge of form and meaning". Hymes (1972) stated that communicative competence should be involved in language capacity. According to Hymes (1972), communicative competence consists of both grammatical competence and sociolinguistic competence. There is a considerable difference between social aspects of learners' first language (L1) and second language (L2) that makes understanding written and oral expressions difficult for non-native reader/hearer. Thus, pragmatic competence in a certain language is best comprehended through enhancing L2 input related to culture and authentic materials (Farashaiyan & Tan, 2012). According to Canale and Swain's (1980) model, pragmatic competence is a significant element of communicative competence that includes three components: grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence and strategic competence. Grammatical competence relates to the learners' abilities to generate grammatically correct sentences. Sociolinguistic competence that covers pragmatic competence refers to the learners' capability to accurately vary their language within different contexts. Strategic competence refers to the learners' capacity to correctly "get one's message across". Then, they defined pragmatic competence as "illocutionary competence, or the knowledge of the pragmatic conventions for performing acceptable language functions, and sociolinguistic competence, or knowledge of the sociolinguistic conventions for performing language functions appropriately in a given context" (p. 90). Later, Bachman (2009) also proposed the language competence model that includes two basic categories with four components: organizational competence (grammatical competence and textual competence) and pragmatic competence (illocutionary competence and sociolinguistic competence). Organizational competence refers to knowledge of linguistic units and the rules of employing them together in a grammatical form (grammatical competence) and discourse (textual competence). Pragmatic competence includes illocutionary competence (knowledge of speech acts and speech functions), and sociolinguistic competence (the ability to serve language appropriately in sociocultural contexts).

2.2. Features of Pragmatics

- Pragmatics focuses on people that use language (Mey, 2001). It also focuses on the way humans employ the language in interactions (Cook, 2000). Belz (2002) believes that language users should use language learned correctly in different contexts and thus they need outside of traditional methods. Context is a vital element that prevents ambiguity in both the spoken and written language. According to Mey (2001), context is "a dynamic, not a static concept: it is to be understood as the continually changing surroundings, in the widest sense, that enable the participants in the communicative process to interact, and in which the linguistic expressions of their interaction become intelligible" (p. 39). In fact, comprehending the language in communication depends on the ability to interpret meaning in context (Levinson, Ryder, Ellis & Hammond, 2003).According to Parks (2000, p. 14), meaning is defined as "search for a sense of connection, pattern, order, and significance...it is a way to understand our experience that makes sense of both the expected and unexpected..." it assists us to make sense of our world. Pragmatics can be defined as the study of specific types of meaning, like "speaker meaning", "contextual meaning" (Yule, 1996, p.3), "meaning in use", and "meaning in context" (Thomas, 1995, p.1). In other words, meaning deal with the way that the humans comprehend their life on an ongoing basis. Nash and Murray (2010) believe that meaning is concerned with those narrative frameworks, interpretations, faith or belief systems, philosophical rationales that every one of us brings to different worlds that we worship, live, learn, work and love.Social interactions are regarded as specific fashions of externalities, that the behavior of reference group affects an individual's decisions (Scheinkman, 2008). In human interactions, language is considered as a vehicle that can show people's feelings, attitudes, personality, intentions, desires, and thoughts (Wierzbicka, 2010). In addition, language is regarded social in nature (Wedin, 2010). In the field of pragmatics, social interactions reveal either spoken communication including at least two people or all types of written and mixed forms of communication (Kasper & Rose, 2002). As a result, it is necessary for English language teachers and learners to be perfectly conscious of various forms of social interactions that can aid them to become socially proficient in communication and to understand how to use this information efficiently (Wierzbicka, 2010).

2.3. Pragmatics and Grammar

- Some researchers such as Bardovi-Harlig (2001) conducted studies that showed that language learners with high levels of grammatical competence do not essentially enjoy high levels of pragmatic competence. As a result, the performance on grammatical competence may not predict performance on pragmatic competence. In fact, the learners that are proficient grammatically may suffer from pragmatic failure and difficulties (Eslami-Rasekh, Eslami–Rasekh & Fatahi, 2004). Thus, grammatical competence is independent of pragmatic competence that is consistent with the claim of some researchers such as Bardovi-Harlig (2001) that believed that a low level of interlanguage grammar does not essentially hinder pragmatic competence from improving.In educational contexts, learners' development of pragmatics has been examined from different theoretical aspects and effective conditions on pragmatic learning have been focused. In addition, the results obtained of findings reveal that explicit teaching is better than implicit teaching (Takahashi, 2010). Learners' improvements of pragmatics and factors that potentially affect pragmatic have been emphasized in educational occasions. In fact, Schmidt (1993) that believed that simple exposure to the target language is not enough for improving pragmatic knowledge provides the rationale for the necessity of instruction in pragmatics. He states that pragmatic functions and related contextual aspects are often neglected even after continued exposure. A classroom approach that teaches children to use conversational knowledge of language functions serves their ability to extract meaning from text and prepares students with a practical way of knowledge transfer. However, in the field of pedagogical intervention in pragmatics, Alcón and Martínez-Flor (2008) claim that although the literature of interlanguage pragmatics signify the positive effect of teaching for L2 pragmatic development, the results are temporary until concluding more researches about the instructional influences of certain target forms in FL classrooms. In order to communicate effectively in the second or foreign language, learners should be able to comprehend the utterances and produce utterances that are regarded contextually appropriate by their target addressee (Kasper & Rose, 2002; Schauer, 2009).According to Cenoz (2007), in order to make the intercultural speaker competent at the pragmatic level, pragmatic awareness must be developed. He believes that although acquiring pragmatic competence is a demanding task, the intercultural speaker has to become an enough speaker to prevent any misunderstanding and failure while interacting with native and non-native speakers of the target language. Therefore, it is significant to make learners conscious of the pragmatic conventions so that they become expert users of the language (Cenoz, 2007, pp. 123-140). The linguistic area of pragmatics in the context of L2 acquisition has been shown in some studies (e.g. Takahashi, 2001, pp. 171-199) for investigating learners' pragmatic competence in their interlanguage. Furthermore, Grossi (2009) investigated on how instructional compliments and compliment responses could be like the adult English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom.In addition, Silva (2003) studied whether rather explicit teaching can be applied to improve L2 pragmatic development, and the most efficient procedures to present the pragmatic knowledge to L2 learners. In fact, the opportunity to improve the L2 pragmatics comes from two basic ways: exposure to input and production of output through L2 classroom use, or from a planned instructional intervention in terms of the acquisition of pragmatics (Kasper & Rose, 2002). Moreover, studies have indicated that many aspects of pragmatic competence cannot acquire without attention to pragmatics teaching (Kasper, 2000). In addition, Schmidt (1993) believed that simple exposure to the L2 is not enough; since learners through only simple exposure do not notice pragmatic functions and relevant contextual aspects; even the learning of L1 pragmatics is facilitated through using some kinds of strategies to teach children communicative competence that is considered more than simple exposure to L2. Therefore, pragmatics instruction could compensate for the limited opportunities for improving competence in a foreign language context. In fact, one of purposes of classroom teaching is to raise learners' pragmatic consciousness (Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford, 1997). The current study aimed to answer the following questions: Does instruction of pragmatic functions through CR develop high school learners' knowledge of language functions?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

- The participants of this study were sixty female junior students of two high schools in Dezfool. They were studying at the first grade of high school and their ages ranged from 14 to 16 years old. They were selected through simple random sampling procedure among the whole students of the high school. In order to see whether they were homogenous, a simulated proficiency test of English extracted from English book1 of high school developed by Birjandi, Soheili, Nowroozi and Mahmoodi (2009) was administered. There was not a significant difference between the participants' level of English proficiency. Then they were divided into experimental and control groups based on systematic random sampling method through which learners were given odd and even numbers from 1 to 60. Students' odd numbers were classified in experimental group and the students' even numbers were put in control group.

3.2. Instrumentation

- Initially, the subjects took the simulated proficiency test extracted from the first grade English book of high school developed by Birjandi, Soheili, Nowroozi and Mahmoodi (2009) to ensure the homogeneity of the groups at the very beginning of the course. The test included forty-four different items consisted of Grammar, Vocabulary, Conversation, Fluency, and Relevance. The mean of the simulated proficiency test was 16.793 and Standard deviation (SD) was 9.437. The reliability of the instrument was estimated through Cronbach Alpha formula and the obtained reliability index was estimated as (α=0.729) which seemed to be an acceptable reliability value (Hatch & Farhady, 1982).The second instrument was a pre-test that was contained thirty multiple-choice items from the two textbooks of Top Notch Fundamentals 1 (A & B) including 14 units on the whole, and each unit comprising three conversations related to the particular topic of that unit written by Joan Saslow and Allen Ascher (2007), and published in the United States of America by Pearson Longman Incorporation, was administered to measure the learners' actual knowledge at the beginning of the treatment. The reliability of the pre-test was measured through KR-21 as (r=.856). Finally, a modified version of pre-test was used as a post-test. It included thirty multiple-choice items administered to determine the effectiveness of experimental and control groups' pragmatic functions instruction of writing. Moreover, in both pre- and post-tests, each item was assigned one point and so the overall score was 30. The reliability of the post-test was calculated through KR-21 as (r=.924).The intra-rater reliability was run to examine the reliability of scoring the writings. The intra-rater reliability of control group's scores on the writings was estimated through KR-21 as (r=.920). The intra-rater reliability of experimental group's scores was estimated through KR-21 as (r=.892). The fourth instrument was a checklist including seven pragmatic functions consisted of Instrumental, Regulatory, Interactional, Personal, Heuristic, Informative, Attention being based on Functional Grammar Book (Halliday, 1985).

3.3. Procedure

- A simulated proficiency test of written English extracted from first grade English book 1 of junior high school (2009) developed by Birjandi, Soheili, Nowroozi and Mahmoodi was being employed to determine the homogeneity level of the participants. The students were selected through simple random sampling procedure. Then they were divided into two groups of experimental and control. The two groups had the same size. A pre-test was being run to ascertain both groups' knowledge on pragmatic functions in writing skill at the initial stages of the study. Then, the explicit instructions were being occurred during one academic semester including eight sessions. The Top Notch 1 (A & B) developed by Saslow and Ascher (2007), as authentic native materials were being effectively used for teaching pragmatic functions in writing process in each session. Thus, the experimental sequence of the study was carried out over a period of around one month. As noted earlier, 60 homogeneous learners were randomly assigned to two groups: an experimental group (EG) and a control group (CG). Around one week prior to the first treatment session, all the participants took the pre-test which was a thirty multiple-choice items test designed to measure the learners' knowledge of pragmatic functions in writing prior to any type of treatment. Then, every group spent eight different treatment sessions. There was an interval of around three or four days between the treatment sessions, and the post-test (another test as an adapted version of the pre-test items) followed the last teaching session around a week later. Each group was taught the same materials with different methods of teaching. The participants of experimental group received an 8-session treatment. Seven pragmatic functions were administered to the students to measure their proficiency on pragmatic functions in writing essays. The experimental group treatment was as the way that this group first listened to a short conversation involving one kind of pragmatic function in focus. Then, they received a scripted version of the conversation, and participated in a series of direct CR (i.e., listening to teacher's explanations about pragmatic functions in writing and also cultural and contextual differences in different situations involved and the meta-pragmatic information on appropriateness of pragmatic functions in writing) and productive (i.e., role play) activities. In other words, the students in the experimental group received instruction and raised their consciousness on the earlier mentioned pragmatic functions in writing and their differences in use and contextual identification and also meta-pragmatic information in terms of their suitable use as well as they had to solve the exercises on the themes in the conversations related to taught session involved in the book as homework for their next session. Those in the control group listened to the conversations and were prepared with the scripts in simply text-type very similarly to the experimental group. The control did not receive any instruction and CR regarding pragmatic functions in writing as the main difference between the experimental and the control group.

3.4. Data Analysis

- To analyze the data quantitatively, descriptive statistics and Independent Samples t-test for comparing the performance of the two groups at the pre-test and post-test were being used. In addition, the students' writings were being scored analytically based on the checklist provided by Halliday's (1985) pragmatic functions. Since this study was designed to focus on the learning of pragmatic functions by EFL learners in writing process, a pre-test and a post-test was run. To analyze the data, the mean scores of different writing components on each case (seven types of pragmatic functions in total) for both groups were being analyzed. It should be noted that since the items in the pre- and post-test were all of multiple-choice items, the KR-21 method was applied to guarantee their reliability. Reliability indexes showed that the tests were acceptable for the purpose of the study. Participants' responses to pre- and post-test items (their use of pragmatic functions in writing) were scored as a single point if they gave appropriate pragmatic answer to each item considering the kind of theme and rules. Responses that were not pragmatically appropriate were given zero. All the correct responses added up to a total sum. One rater scored the tests. Intra-rater reliability coefficients were calculated to meet the reliable scoring on the manuscripts. Then an Independent Sample t-test was run to calculate any prominent difference between the means gained by experimental and control groups on earlier mentioned seven pragmatic functions as well in pre- and post-tests at the level of significant (p<0.05).

4. Results

- This study was an attempt to see to what extent does pragmatic functions instruction through CR affects the students' writing proficiency at the pre-intermediate level. It also aimed at investigating whether pragmatic functions instruction (i.e., noticing, highlighting, and consciousness-raising) have any significant effect on learning pragmatic functions at the pre-intermediate level. This chapter presents the results of the data analysis of the two groups of the study. In addition, it describes the findings of the whole stage of the experiment. For the purpose of this study, descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized to analyze the data. In doing so, first of all the data collected from two groups in pre- and post-test, were analyzed through data gathering after the treatment to find out whether teaching pragmatic functions had any impact on the participants' writing proficiency and their knowledge of pragmatic functions. It should be noted that the data were analyzed through SPSS 17 version. The results are shown in the following sections of the study.

4.1. Results of Descriptive Statistics on the Pre-test

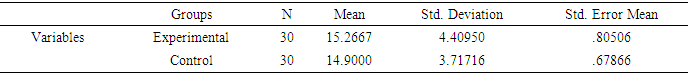

- Descriptive statistics including means, and then standard deviations of the pre-test of the control and experimental groups were computed. They are presented in Table 1.

|

4.2. Results of Independent Samples t-test for the Pre-test

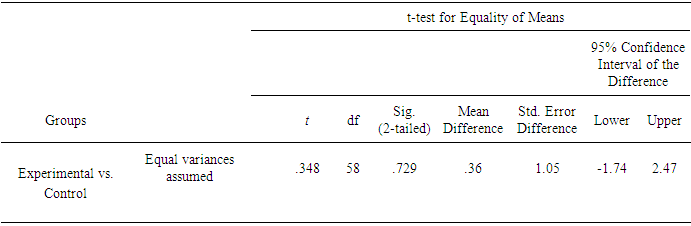

- As there were a dependent and an independent variable, an Independent Samples t-test was run to estimate the scores that are shown in Table 2.

|

4.3. Results of Descriptive Statistics on the Post-test

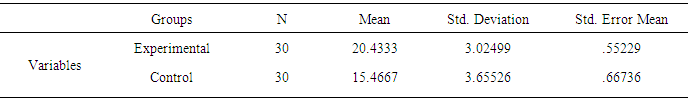

- Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics regarding the post-test scores as it is presented in Table 3.

|

4.4. Results of Independent Samples t-test on the Post-test

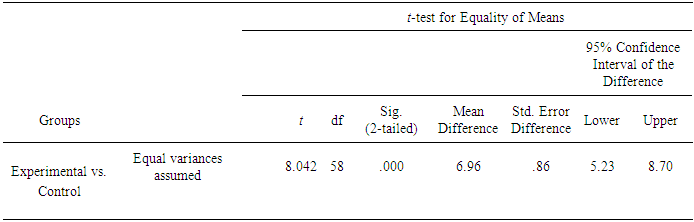

- An Independent Samples t-test was run to reveal the significant difference between the control and experimental groups. The results are shown in the Table 4.

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- The results of the present study along with the research questions will be discussed follows: Do instructing pragmatic functions through CR develop high school learners' knowledge of language functions? The present study indicated the positive effect of pragmatic functions instruction in writing on the experimental students' post-test compared to the control group. The results of Independent Samples t-test analysis revealed that there was a significant difference between the control and experimental groups in terms of pragmatic functions instruction in writing through CR (p< 0.05). By the comparison of mean scores of the post-test participants, the instructional method of pragmatic functions in writing skill appeared much more beneficial to the experimental group rather than to the control one.The scores of the post-test on pragmatic functions in writing indicated that the pragmatic functions in writing through CR have been positively gained by the experimental group. The post-test scores of the experimental group indicated that this group had better comprehension and identification rate of pragmatic functions in writing process on different contexts and situations focused on meaning compared to the control group. Participants who received instructional method of pragmatic functions in the conversations through CR on pragmatic functions in writing process were successful in comprehending the contexts and texts. The participants were asked to pay attention to the highlighted language functions in different contexts and focus on meaning. This is consistent with Craik and Lockhart (1972) who found that the quality of a memory trace depends on the level or depth of perceptual and mental processing where meaning plays a very important role (p. 671-684). In fact, the learners who received consciousness and instruction did significantly better on the post-tests. Therefore, it shows that instruction through CR was effective in leading learners to produce pragmatically appropriate utterances through using them in writing process. This is in accordance with the findings of many previous studies (e.g., Takahashi, 2001) in which the advantages of explicit instruction for L2 pragmatic development was investigated. More specifically, results with regard to the first research question in this study lend further support to those studies on the positive effects of instruction that employed explanation and discussion of rules as their approach to provide learners with pragmatic information (Trosborg, 2003). The present study, in line with previous studies, concludes that learners' ability to write more native like conversations and their comprehension of various kinds of pragmatic functions in different contexts will improve with instruction through CR, although whether or not that knowledge is retained over time is questionable. The pragmatic functions learnt by CR included listening to a short conversation that was included a type of pragmatic function in focus. Then, they received a scripted version of the conversation, and participated in a series of pragmatic instructional and awareness-raising activities consisted of description, explanation, teacher-fronted discussion, small group discussions, role plays, pragmatically focused homework of writing, etc.The pragmatic instruction in writing process through CR for the experimental group began by listening to the conversations and then a teacher-fronted discussion of various meanings a single dialogue might convey in various contexts and situations (e.g. the phrase "Excuse me") that is an interactional function, may be used in order to start and form a dialogue. At the same time, it can also be regarded as an attention-getting function as it is used for trying to ask a question. After teacher, fronted discussion students were divided into different groups and asked to come up with instances of the target pragmatic functions in L1 and L2 and to discuss the similarities and differences in the realization aspects of the pragmatic functions in L1 and L2.The participants were asked to do role-play of the intended pragmatic functions in writing skill for the whole class. Also, the students were provided with dialogues in English in different texts and asked to extract taught pragmatic functions. However, in the control group classroom, no pragmatic instruction in writing process was given and the students were taught in accordance with the usual instructional programs of the high school. The dialogues were read aloud to them with no extra pragmatic explanation. After the completion of the period of around four weeks, the post-test was performed to the participants. The results of this study demonstrate that the experimental group performed better than the control group. Consequently, it can be stated that there is a significant positive effect on the incorporation of the target language pragmatic functions into classroom instruction and the level of pragmatic functions comprehension and production in writing process and the students enjoyed the pragmatic functions that were integrated into the classroom instruction of writing and that the instruction through CR involved greater depth of processing, resulting in knowledge that was firmly embedded. In fact, the evidence indicates that learners with advanced L2 proficiency might lack a successful pragmatic performance in their writings. The results of this study is consistent with Morgan (1989) who proposed that even the learners who have complete understanding of text don't enjoy any metalinguistic understanding of the way of exploring a message and analyze its function. According to Morgan (1989), "Certain pragmatic features are exploited by children's writers for different purposes. Awareness of these elements can deepen comprehension, extend the reader's communicative repertoire, and heighten aesthetic responses" (p. 228). The results of this study can be considered in accordance with Schmidt (1990) who states that learners' noticing of the target features is a need for further second language improvement. He claims that noticing is as a necessary prerequisite to a learner's ability to convert input to intake. Instruction can cause noticing and create consciousness on the part of learners (Brown, 2007). The results of the study run against the idea that various views of L2 pragmatics, both pragma-linguistic and socio-pragmatic, expand effectively without teaching. The reality is that adult learners acquire a great extent of L2 pragmatic improvement free. The cause is that some pragmatic knowledge is universal, some transferable from the learners' L1. But here a caution can be necessary that learners do not always employ what they know, and educational interventions can make them conscious of what they already know and encourage them to apply their universal or transferable L1 pragmatics knowledge in L2 context (Kasper & Rose, 2001). Kasper and Rose (2001) rely on the important role that existing pragmatics knowledge plays in L2 learning and state that language teaching purposefully focuses on this knowledge.By participating in collaborative learning activities and role-playing, the students take advantage of a variety of opportunities to attend gaps in their knowledge and obtain related pragmatic and metapragmatic information in writing process. In fact, the instruction of pragmatic functions through CR in writing may facilitate learners' interaction and collaboration with their classmates in the small group activities and with the guidance of the teacher. This study is consistent with the previous studies on the facilitative influences of teaching on second and foreign language learning in general (e.g. Aksoyalp, 2009; Alcón-Soler, 2005; Doughty, 2003; Kasper, 2001; Kasper & Rose, 2002), and the profits of instruction on writing improvement of students' pragmatic competence in language functions developed by Halliday (1978), in particular.

5.2. Conclusions

- The results indicated that there was a significant difference between the correct responses' percentages of the participants in the control group taught according to the current and traditional approach of writing with no pragmatic instruction and CR in writing skill and the accurate answers percentages of the experimental group taught based on instruction (i.e., noticing, highlighting, and consciousness-raising) on pragmatic functions in writing. The conclusions revealed that on the whole range of Halliday's (1978) pragmatic functions except for imaginative function, the experimental group performed better than the control group. That is, pragmatic functions instruction through CR might significantly affect high school EFL learners' writing proficiency. Therefore, it could be claimed that pragmatic functions instruction should be included in the writing syllabus at the high school since pragmatic competence could be improved in order to increase the students' communicative competence.The conclusions also showed that pragmatic functions instruction in writing skill (i.e., noticing, highlighting, and consciousness-raising) had significant influence on students' learning pragmatic functions in writing process. Furthermore, exposure to conversations in different contexts and by the use of authentic materials is useful activities for high school EFL learners. In fact, incorporating the knowledge of pragmatic functions into the classroom instruction of writing enhances the students' level of pragmatic comprehension and production. As Pierce (1995) believed that language, classrooms provide a desired arena for probing the relationship between learners' subjectivity and L2 use. Classrooms afford L2 learners the opportunity to concentrate on their communicative encounters and to explore with various pragmatic options. For foreign language learners, the classroom can be the only accessible context that they can experiment what using the L2 feels like, and how more or less comfortable they are with various fields of L2 pragmatics. The safe environment of the L2 classroom will thus prepare and support learners to communicate efficiently in L2. But more important than this is to encourage students to explore and focus on their experiences, observations, and interpretations of L2 communicative practices and their own stances towards them, L2 teaching will extend its role from that of language instruction to that of language education. Therefore, activities that increase students' knowledge and use of pragmatic functions in writing skill are necessary. In addition, compared to grammar, vocabulary, semantics, etc. have a subordinate role in enhancing writing proficiency. Therefore, knowledge of pragmatic functions should be included in the criteria of evaluating compositions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML