Khatereh Mousavi, Bahman Gorjian

Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The aim of this study was to find the effective type of timed error correction, including immediate and delayed error correction on the learners’ oral production fluency of Iranian EFL. Thus, in order to investigate this study, 30 homogenous intermediate EFL female learners were selected non-randomly in two intact classes with the age ranging from 13 to 30 from Tak English language institute in Dezful, Iran. The participants were assigned into two groups of 15. They were two experimental groups of immediate and the delayed corrective feedback (CF). They took an oral production pre-test to assess their knowledge of oral fluency at the beginning of the course through topic discussion. In the immediate corrective feedback (ICF) group, errors were corrected immediately and for the second group the errors were corrected with delay, (i.e. 10 minutes). The second group was called as delayed corrective feedback (DCF). During 12 sessions, the students were asked to discuss one of the topics they had covered during the term, while their voices were recorded. Measures of fluency were developed to examine the results based on an oral production checklist. Finally, an oral post-test was given to the participants. Two raters rated the scores and data were analyzed to measure the effect of instruction on the pre and post-test of the two groups. Data analysis indicated that ICF did not affect oral fluency of learners while DCF was significantly effective. Implications of the study suggest that teachers can use DCF to develop learners’ fluency of oral production.

Keywords:

Corrective Feedback, Immediate CF, Delayed CF, Fluency, Oral Production

Cite this paper: Khatereh Mousavi, Bahman Gorjian, Using Error Correction in Teaching Oral Production to Iranian EFL Learners, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2018, pp. 21-29. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20180402.01.

1. Introduction

Speaking skill is one of the most important skills. Mastery over this skill has always been problematic especially among Iranian EFL learners. Restricted by the face-saving culture in Iran, many learners are not brave enough to talk English in classroom. Most of them are scared to talk as they feel they are going to be ridiculed in case of making any mistakes. When they are being corrected repeatedly after making any mistakes, they prefer not talk as they feel they are simply not able to talk correctly at all. Bearing in mind that “speech is silver, silence is gold”, many students choose to keep silent so as to avoid losing face in public (Wang, 2014). Also according to Wang (2014), Affected by such self-restriction, it becomes harder and harder for them to open their mouth as time goes by. Since risk taking is viewed as an essence for “successful learning of a second language” (Brown, 2007, p. 160), Iranian EFL learners should be motivated to speak bravely in order to promote their speaking competence gradually. They should be supported enough before speaking, so that they can lessen their anxiety and perform better in speaking.Choosing an appropriate type of CF has always been given a great deal of attention as poor correction might ruins the learners' motivation, confidence, and consequently the flow of communication, simply put, it can shut the learner up before uttering a sentence. Moreover, teacher should be expert enough to know whether the timing and situation of their correction is the best. Although a great number of studies have been conducted on the impact of efficacy of different types of CF, few researchers have worked on the effect of the timing of the same. According to Dabbaghi (2006), selecting delayed correction type is more preferable and effective than immediate one because when the purpose of speaking is on fluency, errors should be corrected with some delay.

1.1. Objectives and Significance of the Study

Since the act of providing CF can improve students' fluency and accuracy in oral production and committing errors by learners is a frequent activity in language classes, teachers should be aware that which type of error correction can be more beneficial for students. Moreover, in order to avoid the negative effects of poor correction, teachers should select the most appropriate type of correction. Therefore, the results of this study which is to investigate the effects of immediate and delayed error correction on learners' oral production could be valuable for both learners and teachers. The findings of this study might be in line with the theories of Interaction Hypothesis since the main purposes of the current study are to examine the effectiveness of interactional feedback in L2 acquisition, to investigate the effectiveness of different types of CF during interaction, and to find out the most effective type and the best time of interactional feedback in order to avoid interrupting the flow of interaction.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Error Correction

According to Corder (1967), learners commit errors because of lack of knowledge and competence. Burt (1975) claimed, errors in overall sentence organization which hinder communication are “global errors” and errors that affect single elements (constituents) in a sentence without causing hindrance to communication are “local errors” (pp. 56-57). However, learning and speaking a second language, errors are bound to happen as the information is new and students are green to the knowledge they receive. As a part of teaching, these errors need to be corrected be it by teacher himself/herself or by peers. In the present study, error refers to any grammatical or pronunciation mistakes while speaking is happening.Corrective feedback is seen as information given to students when they make an error (Loewen, 2012; Sheen, 2007). Moreover, Ellis (2006) defined the notion of corrective feedback (CF) as “responses to learner utterances containing an error” (p. 28). Correcting students' errors has always been a matter of interest as it needs the right method and the best time to be done. Paying a great deal of attention to the type of CF and the timing is a must for any teacher as it can affect the speaking greatly, be it accuracy or fluency. Choosing the wrong way of correcting and the wrong time brings up nothing but disappointment. Keeping a closed eye on this matter could deprive the students from developing their second language. In the present study, this term refers to correcting learners whenever they make a mistake that happens immediately or with some delay. Furthermore, according to O’Malley and Valdez (1996), oral production is “The way two people share knowledge about what they know taking in account the context of the conversation” (p. 47). People communicate through gestures, facial expressions, body language and more importantly speaking. In this study, the term oral production refers to the ability to speak and producing speech that fits the context. Thus the "capacity to produce speech at normal rate and without interruption” or as “the production of language in real time without undue pausing or hesitation” (Ellis & Barkhuizen, 2005, p. 139).Fluency is an important part of oral production as it affects the communication big time. Being too slow or having many long pauses or many, repetitions not only affect the speaker but also the person who is being talked to. It can make a conversation quite boring, annoying and discouraging. In the present study, this term refers to the ability to speak without too many interruptions, pauses or repetitions.To investigate the role of error correction on Iranian EFL learners, this study aims to answer the following research question: Does immediate error correction have any effect on the fluency of learners' oral production?

2.2. The Role of Corrective Feedback in Learning a Second Language

Since there has been a great emphasis on the notion of CLT (Communicative Language Teaching) as a tool for learning language through interaction in the target language (Nunan, 1991), speaking skill have gained more importance by teachers, learners and researchers during recent decades. Therefore, in order to be able to communicate in the target language and to be proficient in oral production activities, all different factors of this skill should be looked into. One of the main angles of speaking skill is learners’ incorrect utterances and how they should be treated. The learners’ individual differences especially their level of anxiety needs to be considered too. Whereas some scholars (e.g. Gass & Selinker, 2008) believed that errors should be inhibited and eliminated, Corder (1967) mentioned the crucial role of errors in language learning contexts. According to Corder’s attitudes, errors can help teachers to be aware of students’ language learning process and let them to know how much learners have already learnt. In addition, it helps students to discover the rules and structures of the target language. Finally, by considering the notion of errors as an essential part of language learning, researchers notice the way languages are acquired. For the above reasons, researchers and teachers must consider the concept of CF as an essential part of language learning process.According to Long (1996), there are so many factors that may affect L2 learning. One of those factors is the role of interaction which serves as a facilitator device for learning a second language. Long (1996) argued that negotiation for meaning facilitates language acquisition since it can connect input, internal student knowledge and capacities, particularly their selective attention, and output in productive activities. Ellis (2006) defined the notion of CF as reactions to students’ erroneous utterances. In addition, Chaudron (1988) defined it as a complex phenomenon which includes several functions.In addition, Larsen-Freeman and Long (1991) pointed out the powerful role of interactionism theories in explaining language learning processes because they can invoke both innate and environmental aspects. Furthermore, Long (1996) mentioned the crucial role of interaction hypothesis in the SLA process for negotiated interaction. He also claimed that this negotiated interaction might elicit negative feedback and then, induce noticing of some forms.This section reviews the different types and strategies of CF and their roles on L2 learning (especially distinguishing implicit versus explicit types of CF). In addition, it concentrates on recast CF that its main purpose is to avoid interrupting the flow of communication. Furthermore, the principal goal of this section is to define two specific CF types (immediate and delayed), and concentrate on the notion of fluency (which is the main purposes of this study). Finally, this section looks at a number of relevant studies thematically in order to examine the effects of CF and learners' attitudes toward the effects of CF on second language improvement.

2.3. How and When to Correct Errors?

Although, for teachers there are so many ways to treat an error, the way they select for correcting errors may affect the learners’ attitudes towards the target language. According to Akay and Akbarov (2011), there are a few important points that should be concerned in the field of error correction:1. Considering the goals of the lesson, and the learners’ levelsIn learning the objectives of a lesson, CF would be more beneficial to learners when the focus of the error correction is on a particular goal. For instance, if the aim of a lesson is being able to use the irregular forms of past tense verbs in speech, then, for reinforcing that aim teachers should provide a speaking activity, and finally, correct mistakes that are related to the use of those particular verbs. In this controlled setting, learners might remember their specific mistakes and errors from one lesson to the next.2. Encouraging self-correctionTeachers by encouraging learners to correct their own errors, helps them feel that they have sufficient freedom in the classroom and they can control their process of learning by their own hands. In this way, when students are making errors, teachers should indicate that an error has occurred, and must wait for the learner to find out that error and correct it (the learner may do that with the help of her/his classmates). For instance, if an intermediate learner says, “He go to the store”, teacher should stop the learner by repeating what he has said. “He go?” “He go?” The aim is to inform the learner from his/her error and lead the student to re-think about what he/she has said and then correct his/her own error.3. Being aware of when and how to correctTeachers should pay attention to some basic mistakes, and bring them up later. They can write some sentences on the board, which includes some of the same mistakes, and ask learners to find and correct them.4. Do not waste time correcting mistakesIn the field of second language learning, mistakes happen normally in classrooms and are inevitable. Teachers should not waste all the time just for correcting and repeating the correct form, instead they should provide a situation in which learners could learn from their own mistakes.

3. Method

As it was stated above, the current research will be aimed mainly at investigating the effect of immediate and delayed error correction on Iranian EFL learners' oral production fluency. Therefore, in this section some issues such as a brief profile of the participants, who took part in this research, instruments and materials, and data collection and analysis, are explained.

3.1. Participants

The population from which the participants were selected for this study included 50 Iranian EFL learners studying English at Tak Language Institution in Dezful. The participants' ages ranged between 13 and 30 and they were all female students. For the sake of homogeneity a placement test (Oxford Quick Placement Test) was conducted. 50 learners whose scores were included in the intermediate band score (i.e., 30 to 45). 34 students were at the intermediate level. Then, out of those 34 intermediate learners, 30 were selected as the main participants of the study. Then, two experimental groups of 15 were formed non-randomly through convenience sampling method. For the first experimental group errors were corrected immediately and for the second experimental group with a ten minute delay. At the time of the research, the participants studied English in that institute each week three sessions. In their current term, they were supposed to review all grammatical structures (that they had already studied in Four Corner books) to help them to improve their oral proficiency during a term which contains 12 sessions. The participants attended the classes twice a week that were held in the afternoon.

3.2. Instrumentation

In order to accomplish the objectives of the present study, the following instruments were used: the Oxford Quick Placement Test (OQPT) for the pre-intermediate and intermediate learners. The researcher employed a researcher-made pre-test and immediate and delayed post-test was designed based on the textbook and check list (Hughes, 2003) for assessing communicative abilities.

3.2.1. Oxford Quick Placement Test

Oxford Quick Placement Test was administrated in the very beginning in order to determine the proficiency level and selecting select intermediate learners as participants. It included 60 multiple-choice items. Results of the tests were measured according to the acceptable and reliable key answers and conversion chart of the OQPT. The students, whose scores were between 27 and 47, were selected as the intermediate level learners.

3.2.2. Pre-test

A pre-test is a researcher-made test including the test items which were designed based on the conversations of the text books (Four Corners) and the classroom materials. The pre-test was given in the first week during 2 sessions. Since, the main purpose of this study was on oral production, all pre-tests, post-tests, and delayed-post-tests were conducted in the form of structured interviews for each participant. Each interview for each participant was rated by two raters. Their voices were recorded and rated by two raters and the average score was the final score of each participant. The inter-rater reliability was calculated through Pearson Correlation Analysis as (r =.748). The scores were given based on the scales of the checklist (Hughes, 2003).

3.2.3. Post-test (immediate and delayed)

The questions in the interview in immediate and delayed post-test (Appendix C) were similar to the pre-test in content. The scores were given based on the scales of the checklist (Hughes, 2003). Two English experts in Education Organization confirmed validities of the pre-test and post-test. Two raters rated both immediate and delayed interviews and the inter-rater reliability was calculated through Pearson Correlation Analysis (r =.822) and (r=.701).

3.2.4. Checklist

The checklist (Hughes, 2003), assessed communicative abilities that consist of six scales such as fluency, comprehension, communication, vocabulary, structure, and accent. Every scale involved five items (5-1). The checklist was allotted 30 scores. The scores were given based on the researcher-made- test in pre-test and post-tests.

3.3. Materials

Regarding materials, Four Corners 3 and 4, fourth edition intermediate level (Richards & Bohlke, 2012) was used. It consisted of 3 units which took 12 sessions around two months to be taught. The materials used in this study included different topics.

3.4. Procedure and Data Collection

The first session of the study was devoted to the placement test administration (OQPT). For determining the proficiency level of participants, results of the tests were measured according to the acceptable and reliable key answers and conversion chart of the OQPT.Phase 1: The Pre-testIn order to obtain the beginning statistics of the study and examine the learners’ oral proficiency, all participants took part in an oral interview before the treatments. The interview contained four parts. In the first part, instructor showed some pictures and wrote some specific vocabs and verbs related to the topics on the board. In the next part, teacher asked some simple warm-up questions. In part three, learners were allowed to think about the topic (for 1 minute) and be prepared for the discussion. In the last part, each learner was asked to speak about the topic for almost 3 or 4 minutes. The processes of each interview lasted about 10 minutes. The results of the interviews acted as learners’ pre-test of the study. It is worth mentioning that all the procedures of pre-tests were recorded and transcribed later for further examination.Phase 2: The treatment sessionsAfter taking the pre-test, the instructors provided two differing treatments for learners in both groups, i.e. immediate error correction and delayed error correction. The treatments were given during a term which contained 12 sessions in Tak institute, which lasted for about two months. The treatments took about 40 or 50 minutes during each session. During treatment sessions, the teacher selected a particular topic with particular grammatical structure for each session. As a warm-up, the teacher firstly provided participants with some relevant and useful pictures. Then, she wrote some specific relevant vocabularies as well as verbs with their definition. In the next part, participants were asked to discuss the topic in groups or in pairs. After the discussion, the instructor taught the grammatical structures and rules related to the topic. In addition, she mentioned and defined relevant vocabs, verbs, phrases, planned sentences, and idioms. Finally, each participant had to talk about the topic with the use of those particular grammatical structures and words. During these processes, in immediate error correction group (group 1), teacher treated errors immediately when there was a mismatch or non-target like utterance. On the other side, in delayed error correction group (group 2), teacher avoided to interrupt the learners’ speech; in fact, errors were treated with a ten minute delay. Although, the focus of teacher was on providing two types of CF (IEC and DEC), and not considering any other CF types and strategies as the main purpose of research; it was noticed that for the first group (immediate), errors were treated immediately mostly in the form of Explicit CF and on the other side, for the second group (delayed) errors were treated with some delay mostly through using Implicit CF especially Recasts.Phase 3: The immediate post-testAfter the instruction sessions, all learners took part in another oral interview (immediate post-test of the research). To investigate the learners’ knowledge, participants were asked to discuss and speak about the topics that have been covered during the term through the same procedures that were used in the pre-test. Their voices were recorded for further analysis.Phase 4: The delayed post-testAfter an interval of two weeks, again all learners took part in another oral interview (delayed post-test of the study). Then, the findings were recorded and transcribed for further analysis. The procedures and processes used in this phase were similar to one in pre-test and immediate post-test. Delayed post-test was conducted to control the probable effect of time on instruction and learning. A checklist (Appendix B) was used for correcting the tests of oral production.

3.5. Data Analysis

The obtained results were plugged into the SPSS. One-way ANOVA, Independent Samples t-test and Post-hoc Scheffe Test, were used to determine the differences between the two groups’ pre and post-tests.

4. Results

4.1. Introduction

This section aims to provide a detailed account of the results for comparing the effect of immediate and delayed error correction on Iranian EFL learners' oral proficiency fluency. In order to do so, as the first step the obtained results from the pre-tests of two groups were analyzed.

4.2. Results

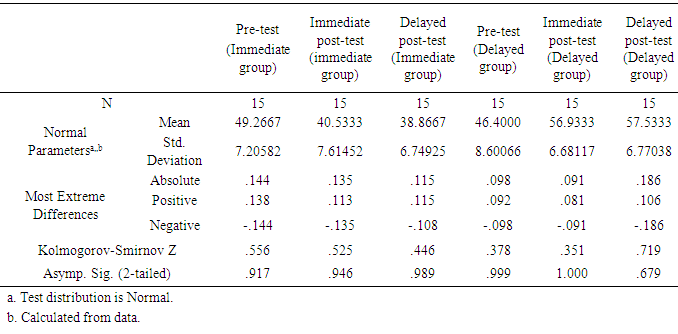

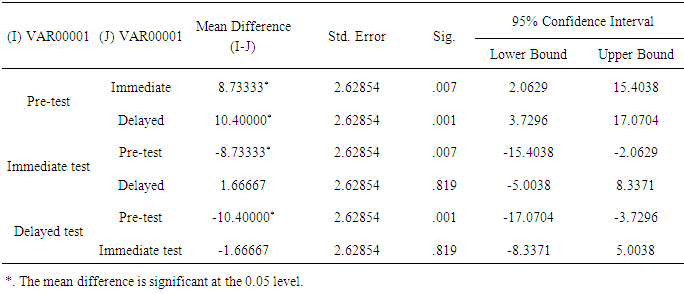

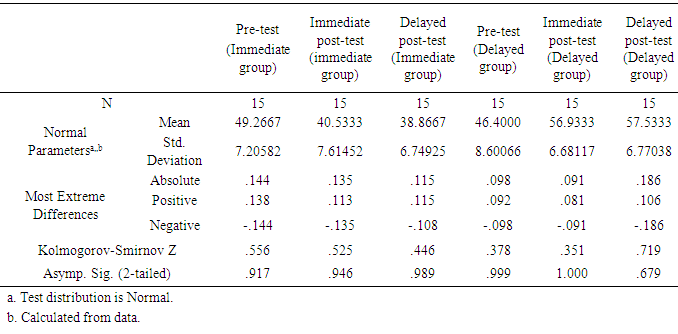

The collected data after the treatment also went through analysis to figure out if error correction had any effect on fluency, be it immediate or delayed. It should be noted that the data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 17. The results of K-S test is presented in Table 1.Table 1. One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

|

| |

|

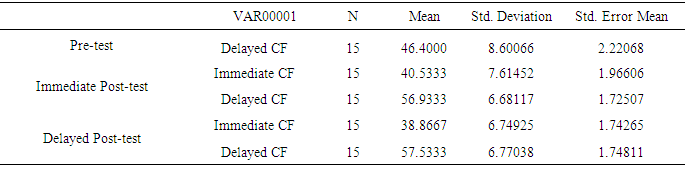

Table 1 represents the normality of data. This is needed to calculate parametric statistics such as One-way ANOVA, Independent and Paired Samples t-test. Descriptive statistics of the pre-test in both immediate and delayed group are presented in Table 2. The results proved the homogeneity of both groups in the pre-test stage.Table 2. Descriptive Statistics (Each group's Pre vs. post-tests)

|

| |

|

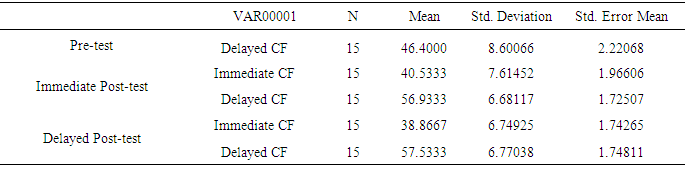

Based on Table 2, the mean and standard deviation of pre-test for immediate CF are 49.2667 and 7.20582 respectively. In case of delayed CF, the mean is 46.4000, while standard deviation is at 8.60066. As it is shown, the means and standard deviations of the two groups are approximately similar on the pre-test. However, the results of immediate and delayed post-tests for each group showed a different picture. As for immediate CF, the mean and standard deviation of immediate post-test are 40.5333 and 7.61452 respectively. While the similar items for delayed CF is 56.9333 and 6.68117. As it is noticed, the scores of two groups on immediate post-test are not similar. And last but not the least, according to the obtained results of delayed post-test, the mean and standard deviation for immediate CF are 38.8667 and 6.74925. While the aforementioned items for delayed CF stand at 57.5333 and 6.77038 respectively, which shows mean and standard deviation are not similar on the delayed post-test. The data were put into Independent Samples t-test analysis to find out the possible differences between the immediate and delayed CF groups on the pre-test, immediate and also delayed post-tests. The results are shown in Table 3. Table 3. Independent Samples t-test (Each group's Pre vs. post-tests)

|

| |

|

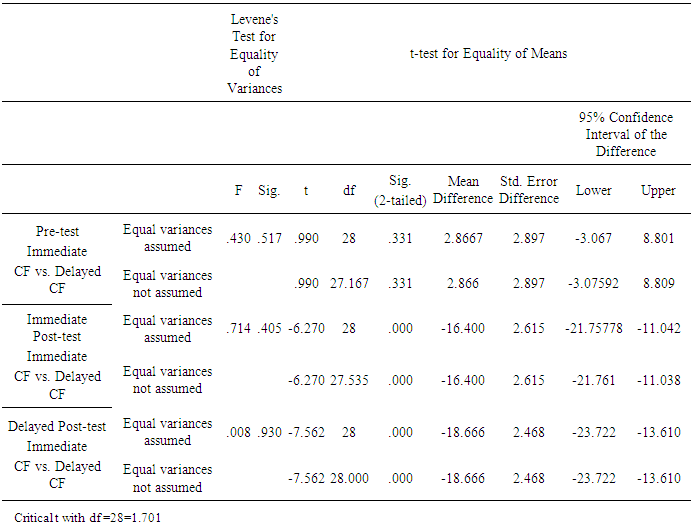

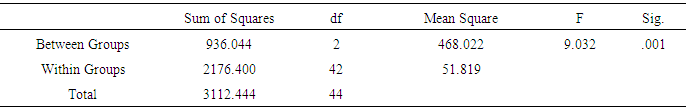

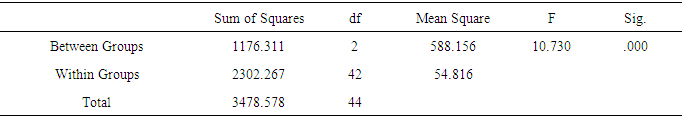

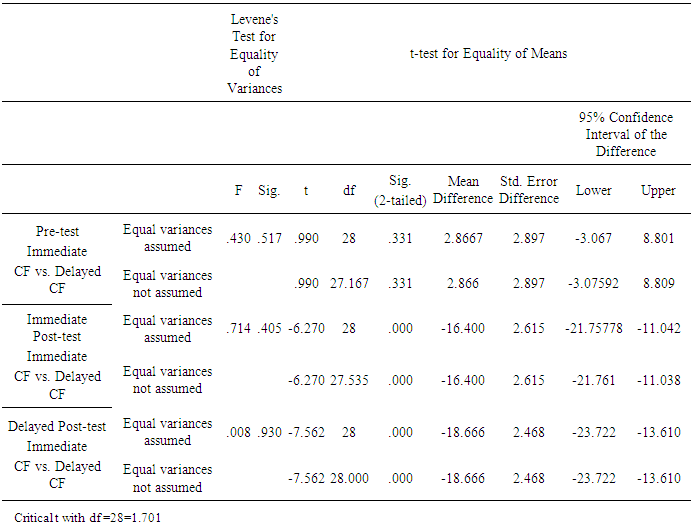

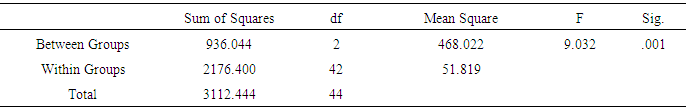

Table 3 shows the results of the Independent Samples t-test for the pre-test, immediate and delayed post-tests of the two groups. In case of pre-test, since the observed t (.990) is less than the critical t (1.701) with df = 28, the difference between the groups is not significant (p<0.05). It can be concluded that both the immediate and delayed CF groups performed similarly on the pre-test, simply put, the number of words used by learners per minute, before treatment were significantly equal. As for immediate post-test, results indicate that the observed t (6.270) is greater than t critical (1.701) with df = 28. Thus, the difference between the two groups is significant (p<0.05). Thus, it can be inferred that two groups performed differently on the immediate post-test. In case of delayed post-test results, since the observed t (7.562) is greater than t critical (1.701) with df = 28, the difference between two groups is significant (p<0.05).Table 4 shows that the observed F value (9.032) is greater than critical F (3.220) with df 2/42, it can also be noticed that the significance value is 0.001 (i.e., p = .001), which is below 0.05. Therefore, there is a statistically significant difference between the three tests in the immediate group’s CF of oral fluency. Table 4. One-way ANOVA (Immediate CF Group, Pre, Immediate, and Delayed Post-test)

|

| |

|

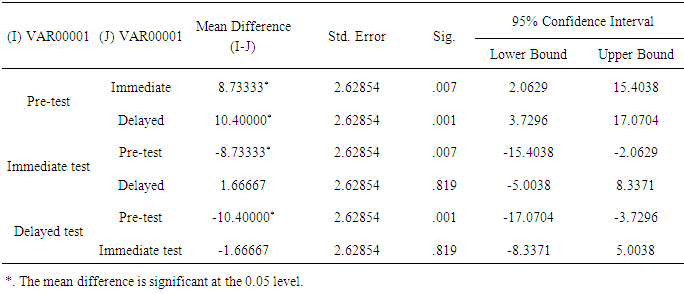

Table 5 shows that for the immediate CF group’s pre-test, immediate and delayed post-test are significantly different as p = .007 which is smaller than 0.05. For the pre-test versus delayed post-test comparison, the significance level is .001. Since this value is smaller than the .05 level required for statistical significance, the results are significantly different. Applying the same procedure to the immediate post-test versus delayed post-test comparison, the results do not indicate any statistical significant difference (sig = .819 which is greater than .05). After comparing the three sets of tests, the final data would show that the results of pre-test are significantly different from immediate and delayed post-tests, but immediate and delayed post-tests are not significantly different from each other.Table 5. Post-hoc Scheffe Test of Immediate CF Group, Pre, Immediate, and Delayed Post-test

|

| |

|

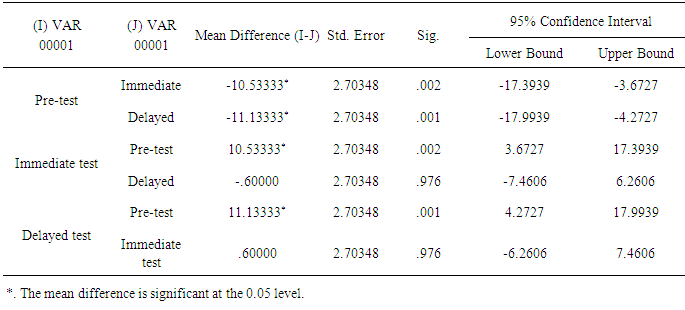

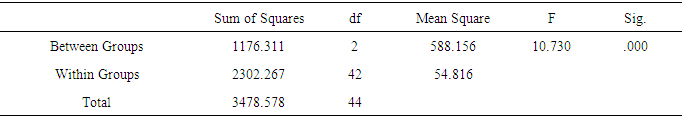

Table 6 shows that the observed F value (10.730) is greater than critical F (3.220) with df 2/42, it can also be noticed that the significance value is 0.001 (i.e., p = 0.001), which is below 0.05. Therefore, there is a statistically significant difference between the three tests in the group’s CF of oral fluency.Table 6. One-way ANOVA (Delayed CF Group, Pre, Immediate, and Delayed Post-test)

|

| |

|

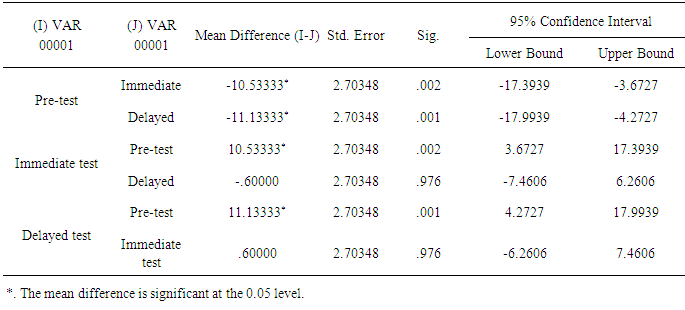

Table 7, compares the results of pre-test and also immediate and delayed post-tests for the delayed CF group. Regarding the pre-test and immediate post-test, the sig stands at .002 which is smaller than 0.05. So, it could be concluded that there is a significant difference. In case of immediate and delayed post-test, p = .001 that is again smaller than 0.05 which is the sign of statistical difference. For the post-test versus delayed post-test comparison, the significance level is .976. Since this value is greater than the 0.05 level required for statistical significance, the difference is not significantly different. After comparing the three sets of tests, the final data would show that the pre-test is significantly different from the immediate and delayed post-tests, but the immediate and delayed post-tests are not significantly different from each other.Table 7. Post-hoc Scheffe Test of Delayed CF Group, Pre, Immediate, and Delayed Post-test

|

| |

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Introduction

This study was aimed to investigate the effect of immediate and delayed error correction on fluency of Iranian EFL learners. This section draws conclusions based on the obtained results of the study. Furthermore, implications, limitations, and recommendations for further studies are presented.

5.2. Discussion

For the purpose of this study which is examining the effect of two types of CF (Immediate and Delayed Error Correction) on fluency of learners’ oral production, three research questions were formed to investigate whether these types of CF had any effect on the improvement of learners’ fluency. Therefore, the findings of this study are in line with a number of studies (e.g., Allwright, 1975; Ferreira, 2006). Furthermore, a number of scholars (e.g. Abid Dawood, 2013; Dabbaghi, 2006) have investigated the effectiveness of CF on oral production in L2 acquisition. This section intends to discuss the obtained results and presents answers to the questions raised in this study. Here the research questions are presented and answered separately as follows:The research question aimed at examining the effectiveness of Immediate Error Correction. In order to answer this question, the results obtained from the pre-test and also immediate and delayed post-tests of immediate CF group were compared and analyzed. Based on the results, while the mean for pre-test was at 49.2667, for immediate and delayed post-test, the obtained mean scores were 40.5333 and 38.8667 respectively, which shows the performances in pre-test and post-tests were quite different. As it could be observed, the decrease of mean between pre-test and post-test was drastic, and this reduction continued in post-test too. Now, the key question is if these differences reach to statistical significance. The results of Independent Sample t-test showed that statistically there was a significant difference between pre-test and the immediate and delayed post-tests (p<0.05) in terms of fluency in oral production. Therefore, it would be right to say that the immediate error correction has negative effect on fluency. Therefore, it could be inferred that the results were not similar on the post-test that is, based on these findings enough support was provided for rejecting the first null hypothesis. These results go with the flow of some studies that were conducted by researchers (e.g., Abid Dawood, 2013; Gharaghanipour, Zareian & Behjat, 2015). They argued that the Delayed type of CF was more preferable and effective in the improvement of learners’ oral production, as they believed immediate error correction has the opposite effect.

5.3. Conclusion

Since the main purpose of second language learning is being able to communicate in the target language, there have been many research studies in the literature regarding improvement in communication and oral production. One important part of this field is how to correct and treat non-target-like utterances. Therefore, considering some aspects that affect the notion of CF such as when and how to correct, and what types of CF is more preferable and effective, is of crucial concern. Although, many studies have been done on the efficacy of different types and strategies of CF especially in written production, few scholars have worked on the effect of time (for example, whether errors should be treated immediately or with some delay) on learners’ oral production and specifically their improvement in fluency. This study was an attempt to determine whether immediate and delayed error correction had a positive effect on improvement of fluency in Iranian EFL learners’ oral production.The results revealed that both immediate and delayed error correction affect the fluency of learners, although, in case of former, the effect was negative, while for the latter, the results were quite positive. Therefore, it could be concluded that while on one hand, correcting learners immediately could be demotivating and it could end up killing their self-confidence, a little delay could do wonders.

5.4. Implications of the Study

This section deals with the implications that the present study may bring out for material designers, language teachers, and language learners. Language studies in the domain of language learning and the use of appropriate corrective CF and the timing of doing so are well advised to take the implications presented in this study. This study could be a striking inception of extensive investigations to be launched into discovering the advantages of when and how to correct the errors over merely traditional instructions.

5.4.1. Implications of the Study for Teachers and Teacher Training

The major reason of learning a foreign language is being able to communicate in that language. So, errors are bound to happen in the process of learning. There are many ways of correcting learners but being able to choose the right one and also the timing of doing so by teacher play a big role. In case, teacher is not skilled enough to know how and when, it could silence the learner forever. This study implies some support for considering IEC and DEC as effective types of CF in the field of second language learning. It also indicates some support for the use of Delayed Error Correction in improving oral proficiency fluency more than the immediate type. In addition, in order to select the most effective type of CF, depending on the specific purpose of the acquisition of a language-learning classroom, teachers should consider different factors for each specific situation. They should be familiarized with the various types, techniques, and strategies of CF. Furthermore; they should be trained to use each of them in an appropriate context, for instance, whether the purpose of acquisition is on improving accuracy or fluency. In this regard, results of this study for fluency improvement in oral production, suggest teachers to provide Delayed type of error correction to learners’ erroneous utterances.

5.4.2. Suggestions for Further Research

Since the main purpose of this study was examining two types of CF (IEC and DEC), it is suggested to conduct similar studies examining the efficacy of other types of CF on accuracy of learners. This study examined the language proficiency of just female participants, thus, it could be replicated with both male and female learners. Considering the fact that this study was limited to only Intermediate learners, similar studies should be conducted with participants at lower or higher levels of language proficiency. Since this study focused on only one aspect of oral production (fluency), similar studies are needed to investigate the other aspects of oral production (such as accuracy and complexity) as well. The present study was limited to investigate only one of the skills of L2 learning (oral production). Therefore, it could be replicated with examining the other aspects and skills of language learning (such as reading, listening, and writing). It is suggested that similar studies should be conducted on examining the efficacy of other types of CF on fluency of learners.

References

| [1] | Abid Dawood, H. S. (2013). The Impact of Immediate Grammatical Error Correction in Senior English Majors’ Accuracy at Hebron University. Unpublished master’s thesis, Hebron University. |

| [2] | Akay, C., & Akbarov, A. (2011). Corrective feedback on the oral production and itsinfluence in the intercultural classes. In: 1st International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. FLTAL, 11, 5-7. |

| [3] | Allwright, R. L. (1975). Problems in the study of the language teacher’s treatment of error. InM. K. Burt & H. D. Dulay (Eds.), New directions in second language learning, teaching, and bilingual education (pp. 96-109). Washington, D.C.: TESOL. |

| [4] | Brown, D. B. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching. (6thed.). NY: Pearson (p. 277). |

| [5] | Burt, M.K, (1975). Error analysis in the adult EFL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 9(1), 53-63. |

| [6] | Chaudron, C. (1988). Second language classroom: Research on teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. van Lier, L. The classroom and the language learner. London: Longman. |

| [7] | Corder, S. P. (1967). The significance of learners' errors. International Review of Applied Linguistics 5, 161-9. |

| [8] | Dabbaghi, A. (2006). A comparison of the effects of implicit/explicit and immediate/delayed corrective feedback on learners' performance in tailor-made tests. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, the University of Auckland. |

| [9] | Ellis, R. (2006). Researching the effects of form-focused instruction on L2 acquisition. AILA Review, 19, 18-41. |

| [10] | Ellis, R., & Barkhuizen, G. (2005). Analyzing learner language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [11] | Ferreira, A. (2006). An experimental study of effective feedback strategies for intelligent tutorial systems for foreign language. In J. S. Sichman, H. Coelho, and S. O. Rezende (Eds.), IBERAMIA-SBIA, volume 4140 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 27–36). Springer, 2006. |

| [12] | Gass, S. M. & Selinker, L. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory course (3rd edition). New York: Routledge. |

| [13] | Gharaghanipour, A. A., Zareian, A., & Behjat, F. (2015). The effect of immediate and delayed pronunciation error correction on EFL Learners' speaking anxiety. ELT Voices- International Journal for Teachers of English, 5 (4), 18-28. |

| [14] | Hughes, A. (2003). Testing for language teachers (2nd Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University press. Larsen-Freeman, D. & Long, M. H. (1991). An introduction to second language acquisition research. New York: Longman. |

| [15] | Loewen, S. (2012). The role of feedback. In A. Mackey & S. Gass (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 24-40). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. |

| [16] | Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). San Diego: Academic Press. |

| [17] | Nunan, D. (1991). Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. TESOL Quarterly, 25 (2), 279-295. |

| [18] | O’Malley, J. & Valdez, P. (1996). Authentic assessment for English language learners. USA: Longman. |

| [19] | Richards, J. C., & Bohlke, D. (2012). Four Corners Student's book. Cambridge University Press. |

| [20] | Sheen, Y. (2007). The effects of corrective feedback, language aptitude, and learner attitudes on the acquisition of English articles. In A. Mackey (Eds.), Conversational interaction in second language acquisition: A collection of empirical studies (pp.301-322). Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [21] | Wang, Z. Q. (2014). Developing accuracy and fluency in spoken English of Chinese EFL learners. English Language Teaching, 7 (2), 110-118. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML