-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2018; 4(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20180401.01

The Comparative Effect of Tea-Party Strategy on Extroverted and Introverted EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Achievement

Farzaneh Javidan, Mehrdad Rezaee

Department of Foreign Languages, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Mehrdad Rezaee, Department of Foreign Languages, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The present study was conducted to examine the effect of tea-party strategy on introverted and extroverted EFL learners' vocabulary achievement. In order to accomplish the objective of the study an Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) test was administered to 90 female learners, this test categorized them into two subgroups (47 extroverted and 43 introverted); Then a Preliminary English Test (PET) was administrated to these 90 participants and 60 participants (30 introverted, 30 extroverted) were selected for the study. A piloted vocabulary researcher-made test was also administered as the pretest and posttest. To test the null hypothesis, two paired sample t-test and one independent t-test were conducted and the null hypothesis was rejected. This study revealed the significant advantage of using tea-party technique to improve the level of language proficiency of both extroverted and introverted learners. Furthermore, the results showed that the extroverted group outperformed the introverted group in learning vocabulary.

Keywords: Tea-party strategy, Extroversion, Introversion, Vocabulary knowledge

Cite this paper: Farzaneh Javidan, Mehrdad Rezaee, The Comparative Effect of Tea-Party Strategy on Extroverted and Introverted EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Achievement, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20180401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- No one can underestimate the important role of vocabulary in learning a language. “If you spend most of your time studying grammar, your English will not improve very much. you will see most improvement if you learn more words and more expressions. You can say very little with grammar, but you can say almost anything with words!” (Thornbury, 2002). The strong relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension has been determined and shown in both L1 (e.g., Anderson & Freebody, 1981; Beck et al., 1987; Nagy & Anderson, 1984) and L2 (August & Shanahan, 2006; Carlo et al., 2004; Carlo, August & Snow, 2005; Wagner et al., 2007). Given this relationship, EFL teachers need to adopt appropriate strategies to help learners learn as much vocabulary as possible from the reading materials in a text. One technique which can be employed in this regard is collaborative learning. Collaborative learning involves an educational method which is concerned with learners' collective attempts at different levels to achieve a common goal (Bruner, 1985). As Johnson and Johnson (1994) maintain, the findings of studies show that learners in collaborative teams can achieve their goals at more advanced levels of thought, performing better in term of information retention compared to individuals who work individually. In fact, engaging in shared learning, students are provided with an opportunity to enter discussion with their peers, assuming responsibility for their own learning. According to Tino & Pusser (2006) when students are working in groups, they will be a part of a community whereby everyone will lend support to one another. This will provide the academic and social support in learning that students need. Seng (2006) found that collaborative learning would increase the chances of academic success. It is also found that when there are fun and interesting communicative activity in the classroom, the students enjoyed working in groups (Seng, 2006).As a pre-reading strategy, the “tea-party activity” involving Reading, Writing and Rising Up by Linda Christensen (2000) who characterized it as an activity which instigates the lackluster readers to read. Christensen suggests that teachers and learners use an appealing passage from the novel or writing a small narrative from the perspective of one of the characters. She makes it clear that her purpose is to make reading intriguing, posing questions for the purpose of making learners familiar with the characters prior to engaging in reading. “Through using the first person for the characters, learners can get into the character’s head more easily” (Christensen, 2000). In the same vein, Jim Burke (2007) asserts that learners need to react to texts in writing. According to Burke (2007), learners enhance their reading skill through focusing on specific sections of the text. This would improve their interpretive or analytical capability. While engaging in the tea party, learners are requested to have a closer look at the relationships between the characters while they may not have any real interactions during the story in the book. According to Beers (2003) tea party strategy has 9 main steps: 1) Creating cards 2) Having students to socialize 3) Returning to small groups 4) Recording predictions 5) Sharing “we think” statements 6) Reading the selection 7) Reflection & discussion 8) Modifications for content area selections 9) Extensions. Learners are allowed to consider portions of the text prior to reading it through the use of this strategy. It also encourages the learners to actively participate in the tasks, listening attentively with ability to get up and move around the classroom. Moreover, this strategy provides the learners with an opportunity to predict what would happen in the text. This is possible through making inferences, working out the causal relationships, comparing and contrasting, practicing sequencing constructively, and drawing on background knowledge (Anderson, 1999). Despite the fact that research has used and examined collaborative learning models in L2 classrooms, little research has been carried out on the impact of the use of the tea-party strategy on vocabulary learning. L2 learning professionals and instructors have turned a blind eye to many potentialities of collaborative learning, in particular, its contributions to vocabulary learning. As already mentioned, the present study seeks to find the possible impact of tea-party strategy on extrovert-introvert students’ vocabulary achievement. In line with the objectives of the present study, the following research question was formulated: Q: Is there a significant difference between the impact of tea-party strategy on introverted and extroverted EFL learners’ vocabulary achievement?

2. Method

- Regarding the nature of the research, the design of this study is quasi-experimental since it made use of two extroverted and introverted groups. More specifically, the design of the current study was pretest-posttest comparison design. This research consisted of an independent variable which was tea-party strategy, while the dependent variable was vocabulary achievement. Moderator variables were extroversion and introversion. Only gender and proficiency level were the control variables of this study.

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.1. Participants

- The participants of the present study were 90 Iranian female intermediate EFL learners studying at Girls Shokuh language school. The age range of the participants was from 14 to 30 years old. Their first language was Persian and none of them had ever experienced living in English speaking countries.

2.1.2. Procedure

- Before the starting of the treatment all students were given Eysenck Personality test (EPI), this test categorized them into two subgroups (47 extroverts and 43 introverted). After the administration of EPI a Preliminary English Test (PET) was administered to these 90 learners, then 60 participants whose scores in PET test fell one standard deviation above and below the mean were chosen. So among these 90 learners two Groups of Extroverted and Introverted which achieved the PET test, each including 30 learners, were selected as two experimental groups. The tea-party instruction lasted for 12 sessions. Preliminary English Test was also piloted among 30 intermediate EFL learners with almost the same language proficiency level and characteristics of the target group who took the tests later; this group took the EPI and vocabulary researcher-made test as well. In the pilot group there were 16 extroverted and 14 introverted. In order to rate the speaking and writing sections of the PET, two expert English instructor cooperated with the researcher. The inter-rater reliability of the two raters established as well. For the empirical investigation of the research question, the following null hypothesis was formulated:H0: There is no significant difference between the impact of tea party strategy on introverted and extroverted EFL learners’ vocabulary achievement.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

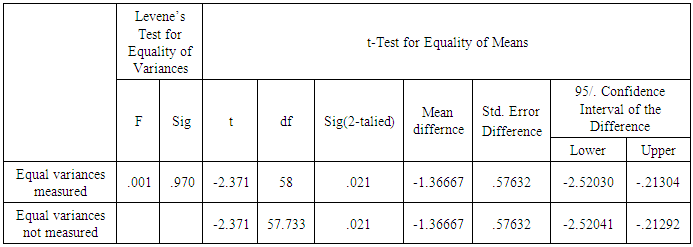

- In order to answer the aforementioned research question and investigate the null hypothesis of the present study, a number of statistical analyses were conducted. The data analysis of this study is comprised of two series of calculations: Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The descriptive statistics (including item discriminations and standard deviations) of PET and vocabulary tests were measured to homogenize items and also to estimate the internal consistency through using Cronbach Alpha. Inferential statistics are used to test the null hypothesis of the study. A paired sample t-test was used to search whether tea-party had any significant effect on extroverted and also introverted EFL learners’ vocabulary achievement, furthermore the independent t-test was utilized to investigate whether tea-party had any significant differential impact on extroverted vs. introverted learners’ vocabulary performance. In addition the inter-rater reliability of two raters’ scores on PET writing and speaking sections was calculated through spearman correlation.

3. Results and Discussions

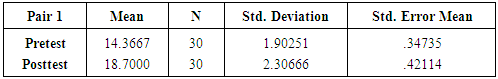

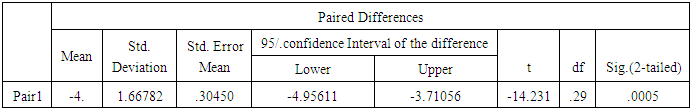

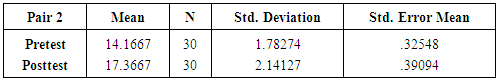

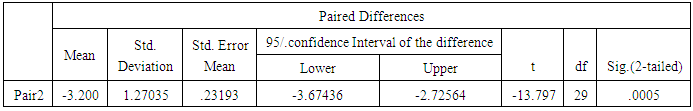

- As it was said before, in order to homogenize the participants PET was piloted to a Sample Group of 30 learners with almost the same characteristics of the main group. After calculating item facility, item discrimination and reliability of the test, the analysis indicated that there were no items that were removed. The reliability of the Sample PET turned out to be 0.832 which was an acceptable index. After ensuring the PET’s reliability, the test was administered to 90 students, the reliability of the PET in this actual administration was also calculated, index of 0.89 reassured the researcher for the reliability of this test. So 30 extroverted learners from 47 extroverted and 30 introverted learners from 43 introverted students who took the PET whose scores fell one standard deviation above and below the mean were selected as the main participants of this study. The descriptive statistics of the groups’ PET scores prior starting the treatment was calculated and it shows that the tests’ mean scores for Extroverted and Introverted groups turned out to be 41.53 and 44.23. As the ratio of skewness/Std Error of skewness for both groups was within the range of -1.96 and +1.96, the researcher was sure about the normality of the distribution of scores. Therefore, the researcher conducted an independent samples t-test to see whether a significant difference existed between the two experimental groups language proficiency prior to the treatment. After conducting the t-test, the results (t =0.104, p = 0.917 > 0.05) indicated that there were no significant difference between the proficiency levels of the two groups at the outset. Hence, the researcher could rest assured that any probable differences at the posttest level would be attributed to the effect of the instruction.In order to demonstrate any possible significant difference in the performance of the introverted group and extroverted group and to verify the null hypothesis of the study, the researcher conducted a paired sample t-test between the pretest and posttest of the extroverts and between the pretest and posttest of introverts separately and then conducted an independent t-test between posttests of the extroverts and introverts. Prior to that, the normality of the distribution of scores within each group had been checked.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The outcome of the posttest and pretest analysis clarified that using tea-party strategy has significant effect on extroverted and introverted EFL learners’ vocabulary achievement both in comparison to their previous stages and also in comparison to each other (Extroverted group outperformed the introverted group). That is to say that the use of tea-party strategy during instruction significantly increased learners’ vocabulary knowledge. Although this study was limited in duration and scope, the results clearly support earlier research on cooperative learning and the effect of tea-party in the domain of vocabulary achievement which found that tea-party techniques have a positive impact on vocabulary knowledge and usage of learners and also establishes enjoyable class time period and group work. As the present study focused on the effect of tea-party strategy on vocabulary achievement of extroverted and introverted EFL learners; the subsequent suggestion is to investigate the role of tea-party strategy in learning language functions and grammar, it is also recommended to investigate the role of tea-party strategy on students’ other skills such as speaking and listening.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML