-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2017; 3(5): 110-116

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20170305.02

The Effect of Teacher Direct and Indirect Feedback on Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners’ Written Performance

Fatemeh Nematzadeh1, 2, Hossein Siahpoosh2

1Department of English Language, Ardabil Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ardabil, Iran

2Department of English Language, Ardabil Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ardabil, Iran

Correspondence to: Hossein Siahpoosh, Department of English Language, Ardabil Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ardabil, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated the effectiveness of different types of teacher's feedback (direct and indirect feedback) on students' writing performance in an EFL context. The initial sample of this study included 73 female Iranian EFL learners who sat for the test voluntarily and they were given a homogeneity test; among them, 45 intermediate learners according to their obtained scores were selected. They were studying English at Nasr Institute in Ardabil, Iran. Their age ranged from 15 to 26. The participants were randomly divided into three groups, namely a direct feedback group, an indirect feedback group, and a no feedback group (each group 15 students). The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed the fact that both types of teacher's feedback enhanced the learners' performance in writing and there was not a statistically significant difference between direct and indirect groups.

Keywords: Direct feedback, Indirect feedback, Writing performance

Cite this paper: Fatemeh Nematzadeh, Hossein Siahpoosh, The Effect of Teacher Direct and Indirect Feedback on Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners’ Written Performance, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2017, pp. 110-116. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20170305.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Like many famous and influential attitudes of teaching, Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) is a standard method used by most teachers to provide guidance in revising students' writing. In many other important and influential approaches to writing, in fact, for most writing teachers, WCF is the most preferred and common form of feedback (Ferris, 1997) and its effectiveness has been investigated over the last twenty years, but it is still not possible to make tough conclusions about which options are the most beneficial to ESL learners.Most of the studies found that feedback is useful and effective in improving student writings. However, there have been feedback contentions on the effectiveness of feedback on student writings (e.g., Fazio 2001; Kepner, 1991; Truscott, 1996, 1999, 2007; Truscott & Hsu, 2008) and repugnant findings in different areas of feedback such as feedback focus and strategy (e.g., Ashwell, 2000; Bitchener, 2008, 2009; Bitchener & Knock, 2009; Chandler, 2003; Ferris, 1999; Ferris & Roberts, 2001; Robb, Ross, & Shortreed, 1986).Furthermore, recent studies (e.g., Bitchener, 2008; Ellis, Murakami, & Takashima, 2008; Sheen, 2007) included a control group, addressed only one error category, and required a new piece of writing as a post-test. However, this study enrich the work by regarding a blend of indirect and direct written corrective feedback, besides investigating the effects of direct and indirect written corrective feedback on Iranian EFL learners’ writing accuracy.The importance of L2 learners’ writing development is not deniable. Since one more important technique of communication is writing, it has come to be seen as a critical language skill to be developed in second language learning. Generally, writing in the second language is the most complex component of language learning which L2 instructors wish to help L2 learners to improve writing proficiency of learners by selecting appropriate methods and procedures.Since speaking is an online task, there is no access to adequate time for removing or composing in it; in contrast, writing provides an invaluable opportunity for L2 learners to apply the new vocabulary and grammatical structures which they have just been exposed to; as a result, this process may promote as well as reflect L2 development. As a matter of fact, speaking using writing activities and exercises helps learners change input into intake. In writing, L2 learners have access to some hidden planning time during which they might attain the opportunity to use those structures and vocabulary items which can be automatized and stabilized as a result of practice in the course of time. Planning time is assumed to promote learners’ attention sources to concentrate on specific aspects of grammatical structures which assist the learners to enhance their accuracy and employ their recently learned knowledge. Providing feedback on writings of students seems to draw their attention toward any possible differences between their writing and norm patterns of writing which are recognized as the target language.But the fact is that, there is a danger of confusion that engages learners during feedback; that is, some learners cannot discover whether their production involves incorrect content or is not native like.

2. Literature Review

- The issue of providing Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) has been a continuous controversy in second language acquisition (SLA). WCF refers to the information that second language (L2) teachers provide in response to learners’ incorrect L2 written output. In the last two decades, the (in) effectiveness of providing WCF for learners’ errors has increased a great deal of controversy among L2 researchers and practitioners (e.g., Bitchener & Knoch, 2009c; Bitchner & Knoch, 2010; Williams, 2012). L2 researchers and practitioners have investigated the effect of written corrective feedback on increasing L2 learners’ writing ability from different aspects. More particularly, they have tested different aspects of WCF, in particular direct and indirect WCF (e.g., Cho & Schunn, 2007), L2 learners and teachers’ understandings about WCF (e.g., Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010), and the person who provides WCF, namely the teacher (e.g., Ferris, 1995; Miao, Badger, & Zhen, 2006; Peterson & Portier, in press).Truscott (2007) claims that the best estimate is that correction has a small negative effect on students’ ability to write accurately. He persists that WCF is harmful feedback because it may impede L2 learners to engage themselves with more complex structures due to the stress of getting wrong; as a result, it influences the complexity of written output.Truscott (1996) insists that WCF neglects the instructional order of learning L2 grammar which learners are supposed to follow. He demonstrates that L2 learners might have no access to declarative (explicit) knowledge or adequate competence to take benefit of the WCF.In contrast, there is a clear evidence (e.g., Bitchener & Knoch, 2008; Brutan, 2009; Ferris, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2002) indicating that WCF grammatical accuracy in new pieces of written and they have counterargued the objections raised by Truscott (1996) with respect to the ineffectiveness and even negative effect of providing WCF on L2 learners’ written output.Ferris (1999) believes that grammar correction is a norm and effective factor. Ferris (1999), in a response to Truscott (1996), claims that this opinion against grammar correction and ineffectiveness of WCF on increasing L2 learners’ writing competence is "premature and overly strong" (p.1). To note that Ferris (1999) supports Truscott (1999) claim about existing body of L2 research studies, examining the effect of WCF on L2 writing have ended mixed results and the rang of studies which have been administered were too restricted.Direct and Indirect WCFA feedback strategy usually used by teachers is direct feedback. Direct feedback is a strategy of providing feedback to students to help them correct their errors by providing the correct linguistic form (Ferris, 2006) or linguistic structure of the target language. Direct feedback is usually given by teachers, upon noticing a grammatical mistake, by providing the correct answer or the expected response above or near the linguistic or grammatical error (Bitchener et al., 2005). Direct feedback has the advantage that it provides explicit information about the correct form (Ellis, 2008). Lee (2008) adds that direct feedback may be appropriate for beginner students, or in a situation when errors are ‘untreatable’ that are not susceptible to self-correction such as sentence structure and word choice, and when teachers want to direct student attention to error patterns that require student correction.There are several studies employing the use of direct feedback on student errors have been conducted to determine its effect on student writing accuracy with variable results. Robb et al. (1986) conducted a study involving 134 Japanese EFL students using direct feedback and three types of indirect feedback strategies. Results of their study showed no significant differences across different types of feedback but the results suggested that direct feedback was less time-consuming on directing students’ attention to surface errors.On the other hand, Chandler (2003) reported the results of her study involving 31 ESL students on the effects of direct and indirect feedback strategies on students’ revisions. She found that direct feedback was best for producing accurate revisions and was preferred by the students as it was the fastest and easiest way for them to make revisions. The most recent study on the effects of direct corrective feedback involving 52 ESL students in New Zealand was conducted by Bitchener and Knoch (2010) where they compared three different types of direct feedback (direct corrective feedback, written, and oral metalinguistic explanation; direct corrective feedback and written metalinguistic explanation; direct corrective feedback only) with a control group. They found that each treatment group outperformed the control group and there was no significant difference in effectiveness among the variations of direct feedback in the treatment groups.Indirect feedback is a strategy of providing feedback usually used by teachers to help students correct their errors by indicating an error without providing the correct form (Ferris & Roberts, 2001). Indirect feedback takes place when teachers only provide indications which in some way make students aware that an error exists but they do not provide the students with the correction. In doing so, teachers can provide general clues regarding the location and nature or type of an error by providing an underline, a circle, a code, a mark, or a highlight on the error, and ask the students to correct the error themselves (Lee, 2008; O’Sullivan & Chambers, 2006). Through indirect feedback, students are cognitively challenged to reflect upon the clues given by the teacher, who acts as a ‘reflective agent’ (Pollard, 1990) providing meaningful and appropriate guidance to students’ cognitive structuring skills arising from students’ prior experience. Students can then relate these clues to the context where an error exists, determine the area of the error, and correct the error based on their informed knowledge. It enhances students’ engagement and attention to forms and allow them to problem-solve which many researchers agree to be beneficial for long term learning improvement (Ferris, 2003; Lalande, 1982).Research on second language acquisition indicates that indirect feedback is viewed as more superior to direct feedback (Chandler, 2003; Ferris & Roberts, 2001) because it engages students in the correction activity and helps them reflect to upon it (Ferris & Roberts, 2001) which may help students foster their long-term acquisition of the target language (O’Sullivan & Chambers, 2006) and make them engaged in “guided learning and problem-solving” (Lalande, 1982) in correcting their errors. additionally, many experts agree that indirect feedback has the most potential for helping students in developing their second language proficiency and metalinguistic knowledge (Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005) and has more benefits than direct feedback on students’ long-term development (Ferris, 2003), especially for more advanced students (O’Sullivan & Chambers, 2006). When asked about their preference for corrective feedback, students also accepted that they realize that they may learn more from indirect feedback (Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005; Ferris & Roberts, 2001).Lalande’s (1982) study, which involved 60 German foreign language learners, compared two different treatments of error correction: direct correction in a traditional manner by providing correct forms to be incorporated by students into their written text, and indirect correction in the form of “guided learning strategies” by providing students with systematic marking using an error correction code. Students were asked to interpret these codes, correct their mistakes, and rewrite the entire essay upon corrective feedback. Results of his study showed that students receiving indirect corrective feedback made significantly greater gains as compared to students who received direct corrective feedback from the teacher. Chandler’s (2003) study involving 31 ESL university undergraduate students shows that indirect feedback with underlining on students’ errors is a preferred alternative to direct correction in a multiple-draft setting as indirect feedback engages the students in the correction process and engages them more cognitively during the process. It is important to note that, in her study where students were required to make corrections, both direct feedback and indirect feedback with underlining of errors resulted in significant increase in accuracy and fluency in subsequent writing over the semester. An additional finding of Chandler’s study is that if students did not revise their writing based on teacher feedback about their errors, getting their errors marked was comparable to receiving no feedback as their correctness did not increase. likely, the study conducted by Ferris (2006), involving 92 ESL students in the United States receiving several types of direct feedback and indirect feedback, shows that there was a strong relationship between teacher’s indirect feedback and successful student revisions on the subsequent drafts of their essays.Ferris (2006) underscored that direct WCF is more likely to improve untreatable errors while indirect WCF might be helpful for treatable errors.In sum, limited number of L2 research studies which have been conducted to date to examine direct and indirect WCF, have not reported cogent evidence which technique i.e., direct WCF or indirect WCF is more effective in improving L2 learners’ writing accuracy.Focused and Unfocused WCFIn unfocused WCF, otherwise known as comprehensive WCF teacher notices and provides feedback to all or most of the errors in L2 learners’ written output. Ellis et al. (2008) considered unfocused WCF as board WCF because it corrects multiple errors. The distinction between focused WCF and unfocused WCF might be generalized to other kinds of WCF. In particular direct WCF and indirect WCF. All in all there has been limited research on the effectiveness of WCF for developing learners’ accuracy in using targeted (focused/selective) and non-targeted (unfocused/ comprehensive) L2 forms and structures. Ellis et al. (2008) suggest that L2 learners prefer to receive correction for specific error types, because this approach is more likely to develop a deeper understanding of the nature of error and correction needed. The proponents of unfocused WCF argued that comprehensive WCF is a beneficial tool at teachers’ disposal because it is more authentic that focused WCF and also it is claimed that unfocused WCF helps learners improve a text revision and writing a new text (Van Beuningen et al., 2012). On the other side, Sheen, Wright, and Moldawa (2009) claim that comprehensive WCF serve as an unsystematic approach for correction written errors committed by learners.Despite of all side, a bulk of WCF studies which have compared the effect of focused and unfocused WCF on L2 learners’ correction of grammatical errors, provided support for the positive effect of focused WCF on improving grammatical features. In a Similar way, the study which has been conducted by Farrokhi and Sattarpour (2012) showed that focused WCF has more effective influence on L2 learners’ writing.Although a significant amount of research has been done on how teachers should provide written feedback in both L1 (Straub, 1997) and L2 (Ferris, 2004; Truscott, 1996, 2004) writing, less research has examined the amount and type of revisions teachers actually recommend students to make (Ferris & Hedgcock, 1998; Goldstein, 2001). Those studies that have done so have demonstrated that often teacher feedback is not text specific, can be incorrect, or may not address the issues that it intends to (Ferris, 2006; Reid, 1993). Moreover, other research suggests that there may be a mismatch between the feedback that students want or expect and the feedback that is actually given (Ping, Pin, Wee, & Hwee Nah, 2003).The Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) literature (e.g., Ashwell, 2000; Chandler, 2003; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005; Polio et al., 1998) indicates that teachers and L2 writing researchers have favored the use of indirect feedback (i.e., where errors are indicated and students are asked to self-correct) and placed the emphasis on the revision process. Relatively few studies have investigated direct feedback (i.e., where learners are given the corrections) by comparing an experimental group and a control group that did not receive any feedback. Moreover until recently, few studies had examined the effect of focused written feedback (i.e., CF directed at a single linguistic feature). Most recent written corrective feedback studies have utilized the methodology employed in SLA research. They have demonstrated that focused CF is facilitative of learning and thus have provided evidence to refute the critics of written corrective feedback (Bitchener, 2008; Sheen, 2007). More specifically, the findings of Sheen’s (2007) study suggest that written CF works when it is intensive and concentrated on a specific linguistic problem. Her study, in effect, constituted a challenge to the traditional, unfocused approach to correcting written errors in students’ writing.Sheen (2007) claimed that L2 writing research investigating written corrective feedback has suffered from a number of methodological limitations (e.g., the lack of a control group as in Lalande, 1982; Robb et al., 1986). For this reason, research findings to date have failed to provide clear evidence that written CF helps learners improve linguistic accuracy over time. Thus, in her study, she examined the effects of direct, focused written CF using a methodology adopted from SLA, which attempted to avoid the kinds of methodological problems evident in many written CF studies.

3. Research Questions

- 1. Does teacher indirect feedback have any effect on Iranian intermediate EFL learners' writing performance?2. Does teacher direct feedback have any effect on Iranian intermediate EFL learners' writing performance?3. Is there a significant difference among the effects of the three types of teacher feedback (indirect feedback, direct feedback, and no feedback) on Iranian intermediate EFL learners' writing performance?

4. Methodology

- Participants To accomplish the objectives of the present study, 73 female Iranian EFL learners who sat for the test voluntarily, were given a homogeneity test; from among them, 45 intermediate learners according to their obtained scores were selected. They were studying English at Nasr Institute in Ardabil, Iran. Their age ranged from 15 to 26. The participants were randomly divided into three groups, namely a direct feedback group, an indirect feedback group, and a no feedback group (each group 15 students). The homogeneity of participating groups in terms of L2 proficiency was assured through Preliminary English Test (PET).ProceduresFirst the Preliminary English Test (PET) was administered to 73 intermediate students to homogenize them regarding their general English proficiency. Out of 73 students, 45 students were selected. Then, the selected participants were randomly assigned to three groups, two experimental groups with 15 students in each group and a control group with 15 students too.Second, the pre-test of writing was administered to make sure that the participants’ writing ability at the beginning of the study in all three groups was the same. The students were asked to write a three paragraph essay of 100-150 words in 30 minutes.Then, the treatment period began and was continued for 10 sessions. The learners attended the class two days a week. Each session lasted for 90 minutes in all groups. Three different treatments were included in this study; (a) direct corrective feedback (DF), (b) indirect corrective feedback (IF), (c) no feedback (NF). In the first session of treatment the investigator explained the articles, prepositions, and tense of verbs for all groups. Then the students were given one TOEFL writing topic for each session.Students in the direct and indirect treatment groups received comprehensive direct or indirect corrective feedback respectively on the paragraph they created. In direct feedback group, the researcher indicated and located the errors by drawing lines under the incorrect parts and by writing short comments, then their papers were given back to them after correction. Then the students were asked to revise their writings and submit them to the researcher the next session. For the indirect corrective feedback, she just marked their mistakes and underlined the incorrect forms but didn't correct them for the students. In the control group, the learners received almost no specific training on the corrective feedback techniques; however, they enjoyed the same materials and other traditional writing strategies which were employed to help them develop their writing ability.After 10 sessions of treatment, the post-test of writing was administered to check the learners’ writing development. Both control and experimental groups were asked to take a writing test. Then the data were gathered and analyzed through SPSS version 21.

5. Results

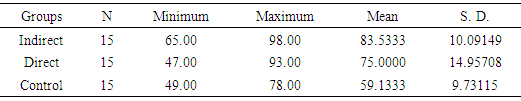

- The descriptive statistics of posttest writing for all groups are presented in Table 1.

|

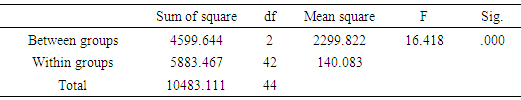

|

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- The current study was conducted to investigate whether there was a differential effect on accuracy for three different types of written corrective feedback (WCF) options on writing of L2 learners in EFL context. The current study was conducted to investigate whether there was a differential effect on accuracy for three different types of written corrective feedback (WCF) options on writing of L2 learners in EFL context. As mentioned earlier, both pre-tests and post tests were scored by independent raters based on the Essay Scoring Rubric. Each essay was read by two raters, correlation test was performed between the scores given by two raters to the same writing to check the inter-rater reliability, and the results obtained from Pearson Correlation indicated there was a positive significant relationship between the scores given by the two raters. The differences between the pretest and posttest writing performance results of two experimental groups (indirect feedback and direct feedback) suggested that both types of teacher’s feedback had enhanced learners’ performance in writing. According to Ferris (2003), WCF is a pedagogy that is often used when helping learners improve their written accuracy. The results of the study are in line with Eslami (2014). Eslami investigated the Effect of Direct and Indirect corrective feedback techniques on EFL Students' writing and found that the indirect feedback group outperformed the direct feedback group on both immediate post-test and delayed post- test. Moreover, the results of the study are in agreement with Sadeghi, Khonbi and Gheitranzadeh (2013). They have explored the effect of gender and type of WCF on Iranian pre -intermediate EFL learners’ writing. Sadeghi et al. found that students who received direct WCF performed significantly better than those who received indirect WCF and those in control groups and gender had a significant impact on the learners' writing ability with females performing better than males. Besides, the results of the study are on a par with Baliaghizadeh and Dashti (2010). In investigation of the effect of direct and indirect corrective feedback on students' spelling errors, revealed that indirect feedback is a more effective tool than direct feedback in rectifying students' spelling errors.In sum it is notable that different types of WCF, namely direct, and indirect feedback have their significant role in increasing the accuracy of learners output. However, corrective feedback is therefore essential for both the Instructional Designers and learners. Corrective feedback must be provided frequently to be helpful. In addition, feedback should not only concentrate on the corrective aspect, but should be justified.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML