-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2017; 3(4): 88-96

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20170304.02

Teaching Grammar to EFL Learners through Focusing on Form and Meaning

Faeze Bandar1, Bahman Gorjian2

1Department of TEFL, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

2Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The current study investigated the impacts of focus on form and focus on meaning on the learning of Wh-questions among senior high schools in Abadan, Iran. The participants were 60 male students who were selected among 100 learners non-randomly. They were studying English at a senior high school. They were aged between 15 and 17. In order to have homogeneous groups, the learners were given a grammatical test to determine their proficiency level. The teacher- made Wh-questions test based on the book one of high school was given to them as the pre-test. Then, they were assigned into two equal groups of experimental and control groups. The experimental group received instruction on focus on form and meaning but the control group was taught in the traditional way of teaching grammar including the use of examples and sentence exercises. Both groups received eight sessions of treatment, each 45 minutes with the same materials; and then they took a post-test at the end of the course. Data were analyzed through Independent and Paired samples grammar of Wh-questions post-test. The results showed that the experimental group outperformed the control one (p<0.05). Implications of the study for English teachers suggest that they should focus on form and meaning simultaneously to provide their learners with effective instruction. This study is expected to have theoretical and practical importance to get an insight in to the effect of focus on form and meaning simultaneously on student’ ability to understand English as used by native speakers.

Keywords: Focus on form (structure), Focus on meaning, Wh-questions

Cite this paper: Faeze Bandar, Bahman Gorjian, Teaching Grammar to EFL Learners through Focusing on Form and Meaning, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2017, pp. 88-96. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20170304.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Focus on form (FonF) is an approach to language education in which learners are made aware of the grammatical form of language features that they are already able to use communicatively. Focus on form is an instructional way which draws learners’ attention to linguistic forms within communicative contexts. It requires a prerequisite engagement in meaning before achieving successful learning of linguistic forms. In addition, it often consists of an occasional shift of attention to linguistic code features by the teacher and/or one or more students triggered by perceived problems with comprehension or production. Therefore, focus on form has some psycholinguistic plausibility in that it encourages learners to pay conscious attention to certain forms in the input, which they are likely to ignore. Such attention is necessary for acquisition to take place and can be thought of as a useful device which facilities the process of inter language development, (Long & Robinson, 1998). The meaning-focused approach grew out of the dissatisfaction with form-focused approaches such as grammar translation and cognitive code methods. It has been argued that there was a mismatch between what was learned in the classroom and the communicative skills needed outside the classroom. The problem of Iranian EFL learners is that most of them have difficulties in learning grammar particularly Wh-questions (Rahimpour & Maghsoudpour, 2011). Hence, the present study will be conducted to find the effect of focus-on-form and focus on meaning on learning Wh-questions among Iranian senior high school students. Focus on form has been one of the hotly debated issues in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) over the past two decades. Mastering the grammar of a second/foreign language and being able to correctly implement this knowledge is a demanding and challenging task to accomplish, which is the reason for many English as a second language (ESL) students to find it difficult to express themselves accurately in speech or writing (Farahani & Sarkhosh, 2012). Furthermore, the mastery over linguistic elements as an element of pragmatic competence in language learning, and the complex nature of SL pragmatic development presents learners of English as a second language and their classroom instructors with significant challenges. Taking these challenges into account, (including instruction) that may contribute to this development is a worthwhile goal. In the context of classroom instruction, several studies (e.g, Ellis, 2008) suggest that explicit instruction promotes development. This instruction can be implanted within Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) as focus on form.Focus-on-form should be integrated into communicative curricula and that as each student has a point of readiness for focus-on-form and every form may be ideally suited to different degrees and kinds of focus-on-form, teachers should be always aware of student’ inter-language and develop alternative instructional strategies. That is, teachers should be careful about students’ linguistic development and timing of giving them task. Farrokhi, Rahimpour and Papi (2011) suggest the importance of the combinations of explicit and implicit focus on form and also possibility of crossover from focus-on-form to focus-on-forms. Consequently, selection of forms and timing to focus on them will be important in accordance with learners’ linguistic development of L2.Focus on form is a broad concept that was a drastic change and it is better to say it was a revolution from focus on forms. However, several Iranian teachers and learners may have been deprived of this change and its contributions. Grammar is a crucial part of language teaching and it plays an important role in language. In order to speak accurately, a person needs to know grammar. Teaching grammar by formal instruction can be so easy for teachers, if they feel secure and even the students have feeling of security but it was proved that it is not so much effective (Long, 1991). Most EFL learners in Iran may face difficulties using Wh-questions properly in written or spoken settings. The current study investigated the visible impacts of focus on form and focus on meaning on the learning Wh-questions on intermediate EFL learners at high school in Khorramshahr, Iran. During the eight sessions of the treatment, they experienced learning English Wh questions in particular and grammar in general. In simple terms, the fundamental purpose behind the current document was examining the impact of focus on form and focus on meaning on grammar improvement of Iranian EFL learners in general and Wh-questions in particular. Because the students have difficulty how to make question with Wh-questions this study investigates if the learners know the meaning of Wh-questions and their form they can cope with this problem. As some classes have been observed, not only is the focus of teachers on vocabulary but also they teach grammar traditionally.

2. Review of the Literature

- Since grammar has been described as the regular system of rules that we use to weave sounds into the meaningful units with which we express our thoughts and ideas, creating language, it has come to be the “skeleton” of language. It means that it is not possible to teach a language without taking into consideration its grammatical structures. Grammar is merely a set of rules to preserve the written word. Without these standards there would be no continuity of language and over time communication of ideas would suffer. As people from different parts of the world try to talk in English which is influenced by their own mother tongue, there are errors in grammar and sentence pattern. If one can master grammar, he or she can unlock ideas and thoughts that were written across time and place. Proper grammar is very important. Correct grammar keeps from being misunderstood and lets us effectively express our thoughts and ideas. The way we communicate is extremely important in our profession and society. While modern technology and social media have less formal forms of communication, we are expected to produce perfect grammar in professional settings. According to Ellis (2008), grammar gives language users the control of expression and communication in everyday life. Mastery over the words help speakers communicate their emotions and purpose more effectively.Over the past few decades, the focus of classroom instruction has shifted from an emphasis on language forms to use of language within communicative contexts. This has brought about the question of the place of form-focused instruction (FFI) in classroom activities (Brown, 2000). In chapter two the theoretical and experimental studies related to focus on structure and focus on meaning will be presented. The theoretical background of the resent works will be discussed in the next section.Focus on form (FonF) has evolved from Long’s instructional treatment that “overtly draws students’ attention to linguistic elements as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning or communication” (Long, 1991, pp. 45-46) into such tasks as processing instruction, textual enhancement and linguistic or grammar-problem solving activities. The key tenet of FonF instruction is meaning and use being present when the attention of the learner is drawn to the linguistic device which is necessary for comprehension of meaning. The call for FonF is often triggered by learner problems or difficulties usually resulting in a breakdown in communication. The problematic linguistic features come into instructional focus to help learners get back on track. Apparently, when learners are left to their own resources, they do not try to pay attention to linguistic characteristics of their communicative activities. Thus some form of instructional focus on linguistic features may be required to destabilize learners’ interlanguage (Ellis, 2009). The positive role of FonF in second language acquisition (SLA) has often been recognized over the past two decades. Norris and Ortega (2000) indicate that such studies have demonstrated evidence that FonF facilitates second language (L2) learners’ acquisition of target morpho-syntactic forms or features. He further maintains that current concern has shifted to what constitutes the most effective pedagogical techniques in specific classroom settings, considering the choice of linguistic forms, the explicitness, and the mode of instruction. In short, focus on form instruction is a type of instruction that, on the one hand, holds up the importance of communicative language teaching principles such as authentic communication and student-centeredness, and, on the other hand, maintains the value of the occasional and overt study of problematic L2 grammatical forms, which is more reminiscent of non-communicative teaching (Long, 1991). Furthermore, Long and Robinson (1998) argue that the responsibility of helping learners attend to and understand problematic L2 grammatical forms falls not only on their teachers, but also on their peers. In other words, they claim that formal L2 instruction should give most of its attention to exposing students to oral and written discourse that mirrors real-life, such as doing job interviews, writing letter to friends, and engaging in classroom debates; nonetheless, when it is observed that learners are experiencing difficulties in the comprehension and/or production of certain L2 grammatical forms, teachers and their peers are obligated to assist them notice their erroneous use and/or comprehension of these forms and supply them with the proper explanations and models of them. Moreover, teachers can help their students and learners can help their peers notice the forms that they currently lack, yet should know in order to further their overall L2 grammatical development.

2.1. Corrective Feedback and Focus on Form

- Feedback that a teacher or learner provides in response to a learner utterance containing an error. The feedback can be implicit as in the case of recasts or explicit as in the case of direct correction or meta-lingual explanation (Ellis, 2005). Corrective feedback is a necessary part of learning a language, especially in a F on F model. Students are not able to learn from their mistakes if those mistakes are not pointed out to them or if they are not given the tools to correct them. According to the Interaction Hypothesis (Long, 1991), corrective feedback plays a beneficial role in facilitating the acquisition of certain forms ,which may be otherwise difficult to learn or master through exposure to comprehensible input alone (Long & Robinson, 1998). Corrective feedback, moreover, can be used to draw learners' attention to mismatches between the learners’ production and the target like realization of these forms. According to Ellis (2009), direct corrective feedback refers to when the instructor indicates where a mistake has been made and immediately provides the correct answer for students. On the other hand, indirect corrective feedback occurs when the instructor indicates that there has been a mistake but does not give the student the correct answer. This form of feedback is helpful in long-term acquisition of grammar and concepts, and it also creates a problem-solving environment in the classroom. Thus corrective feedback may be defined as a teacher's reactive more that invites a learner to attend to the grammatical accuracy of the utterance which is produced by the learner. The most comprehensible taxonomy of corrective feedback has been provided by Lyster and Ranta (1997). Lyster and Ranta developed an observational scheme which describes different types of feedback teachers give on errors and also examines student uptake- how they immediately respond to the feedback. This resulted in the identification of six feedback types defined below:1. Explicit correction: refers to the explicit provision of the correct form.S: The dog run fastly.T: "Fastly" doesn’t exist. "Fast" does not take – ly. You should say ‘fast’.2. Recasts: involve the teacher’s reformulation of all or part of a student’s utterances, minus the error. Recasts are generally implicit in that they are not introduced by ‘You mean’, ‘Use this word’ or ‘You should say’.S1: why you don’t like Mark?T: why don’t you like Marc?S2: I don’t know, I don’t like him.Note that in this example the teacher does not seem to expect uptake from S1. It seems she is merely reformulating the question S1 has asked S2.3. Clarification requests: The teacher indicates to students that their utterance has been misunderstood by the teacher and a repetition or reformulation is needed.4. Meta-linguistic feedback: contains comments, information, or questions related to the correctness of the student’s utterance, without explicitly providing the correct form, (for example, can you find your error?’)5. Elicitation: refers to techniques that teachers use to directly elicit the correct form from the students.6. Repetition: refers to the teacher’s repetition of the student’s erroneous utterance.Among these categories, recasts will be considered in this study. A considerable amount of recast research, both in and out of classrooms, has concerned recasts: implicit reformulation of learners' non-target like utterances (Ellis & Sheen, 2006).S: There was fox.T: There was a fox. S: The boy has many flowers in the basket.T: Yes, the boy has many flowers in the basket.

2.2. Reactive vs. Proactive Focus on Form

- Being inadequate to provide language learners with enough evidence for language learning, positive evidence should be presented to learners along with negative evidence. One option to present negative evidence is reactive focus on form, which involves the treatment of the learners’ erroneous utterances upon their occurrence and is therefore a priori. This appears to be what Long (1991) had in mind in conceptualizing focus on form. Reactive focus on form could be either conversational or didactic. According to Ellis (2002), the former occurs when there is a breakdown in the flow of conversation resulting in the teacher addressing an error through negotiating of meaning. On the other hand, sometimes the problem may not be serious and hence does not impede communication; however, the teacher chooses to fix the error, as when a learner leaves out a definite article. The focus-on-form episode that grows out of this type of error treatment constitutes a kind of pedagogic ‘time-out’ from meaning-focused communication and for this reason can be considered didactic (Ellis, 2003). Another distinction that has been made is between reactive and preemptive focus on form (Long & Robinson, 1998). While Long claims that focus on form is purely reactive, Ellis (2001) claims that it comes in two forms; preemptive focus on form and reactive focus on form. Reactive focus on form has also been known as error correction, corrective feedback, or negative evidence/feedback (Long, 1991), and occurs when, in the context of meaning-focused activities, learners’ attention is drawn to errors in their production. Long and Robinson (1998) state that reactive focus on form involves a responsive teaching intervention that involves occasional shifts in reaction to saliently errors using devices to increase perceptual salience. On the other hand, the proactive research involves making an informed prediction or carrying out some observations to determine the learning problem in focus. Long and Robinson believe that by taking this stance, there is no need to restrict focus on form to classroom learners’ errors which are pervasive , systematic, and remediable for learners at that particular stage of development, which is a burdensome selection process. However, Doughty and Varela (1998) comment that this reactive stance is not practical when the learners are of different L1s, of different abilities, or of such high ability that errors go unnoticed by the teacher or other learners, since the message is successfully delivered. They further add that reactive stance may be most appropriate with same-L1-background learners, and with experienced- enough teachers to have some idea of what to expect, taking into account that an on-line capacity for teachers to intervene and deal with all errors places too much demand on the teachers. Regarding the difficulties in proactive focus on form, first, three concepts related to task are introduced by Loschky and Bley-Vroman (1993). The first is the task of naturalness in which a grammatical structure may appear naturally during a task which could be still carried out perfectly even without that structure. The next is the task of utility in which the task could be carried out with that particular structure more easily. The last one is the task of essentialness which refers to the time when the task could not be carried out at all without that particular structure.Focus on form should not be confused with 'form-focused instruction'. The latter is an umbrella term widely used to refer to any pedagogical technique, proactive or reactive, implicit or explicit, used to draw students' attention to language form. It includes focus on form procedures, but also all the activities used for focus on forms, such as exercises written specifically to teach a grammatical structure and used proactively, i.e., at moments the teacher, not the learner, has decided will be appropriate for learning the new item. Focus on form refers only to those form-focused activities that arise during, and embedded in, meaning-based lessons; they are not scheduled in advance, as is the case with focus on forms, but occur incidentally as a function of the interaction of learners with the subject matter or tasks that constitute the learners' and their teacher's predominant focus. The underlying psychology and implicit theories of SLA are quite different, in other words. A focus on form entails a focus on formal elements of language, whereas focus on forms is limited to such a focus, and focus on meaning excludes it. Most important, it should be kept in mind that the fundamental assumption of focus-on-form instruction is that meaning and use must already be evident to the learner at the time that attention is drawn to the linguistic apparatus needed to get the meaning across. The purpose of this chapter was to review and to explore how the present study was aligned with current views in the field. This part of this chapter was to investigate the effects of teaching Wh-questions in English through focus on form. Therefore, some essential fundamental aspects, which provided information on characteristics and theoretical aspects of some terms related to this study, needed to be highlighted in this section.

2.3. Research Questions

- This study aims to investigate the answer to the following research questions:RQ1: Does focus on meaning technique affect teaching Wh-questions to Iranian senior high school EFL learners?RQ2: Are there any differences between focus on form and traditional ways in teaching Wh-questions to Iranian senior high school EFL learners?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

- In order to conduct the study, the researcher selected 60 students, with the age ranging from 15 to 16, out of 100 students from among four classes at the same level of senior high school students in Abadan, Iran. Their mother tongue was Arabic, Persian or bilingual of both. They were all in the first grade of high school. Non-random sampling method was used for the selection of these participants. Then they took part in Wh-question pre-test which was used as a homogeneity test and sixty students whose scores were one standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the mean were chosen as the participants of the present study. They were randomly (i.e., systematic random sampling method) divided into two groups, one experimental and one control. Each group included 30 participants. The experimental group received focus on form and meaning simultaneously while the control group received the focus on form and grammatical formulas.

3.2. Instruments

- In order to accomplish the objective of the present study, the following instruments were employed:1. Pre-test: A pre-test which contained the actual test items was administered i.e., based on the classroom materials to the participants before treatment in order to determine how well the participants knew the contents before the treatment. This test was also used as the homogeneity test to determine the participants' level of Wh-question proficiency. The participants were asked to answer 25 multiple-choice Wh-questions selected from the course passages in 25 minutes. The reliability value of the test was piloted on eight students at the same level before to meet the reliability index. Its reliability was calculated through KR-21 formula. The reliability of the pre-test was (r= 0.728).2. Post-test: Following the treatment, eight weeks later after the end of the course, the instructor showed up in the class to administer the post-test. All characteristics of the post-test were the same as those of the pre-test in terms of time and the number of items. The only difference of this test to the pre-test was that the order of questions and alternatives were changed to wipe out the probable recall of pre-test answers. Both the pre-test and the post-test were performed as part of the classroom evaluation activities under the supervision of the instructor. The reliability value of the test was piloted on eight students at the same level before to meet the reliability index. Its reliability was also calculated through KR-21 formula as (r=0.903).

3.3. Materials

- After dividing the participants into two equal groups of 30 in the control and experimental groups, the treatment began. Grammar points based on high school books (book 2) were taught to the learners throughout the term including grammar points. They were taught to the learners by resorting to focus on form and focus on meaning strategies. They consisted of many texts which were taught during eight sessions in one semester. The main content of these texts was learning grammar points specially Wh questions. Similar to the pre-test, the final post- test included 25 questions and it was conducted at the end of the treatment. The time of exam was 30 minutes.

3.4. Procedure

- At first, researcher-made grammar test was used focusing on Wh-questions as a pre-test and also determining the participants' homogeneity level. In the next step, learners were divided into two different equal groups as the experimental and control groups receiving different instructions: the experimental group experienced Focus on Form and meaning Instruction and the control group paved their way in the normal traditional method. The first group was experimental group, and the second group was control group.In focus on form group being involved in grammatical tasks, the teacher introduced the topic by asking Wh-questions about the text in order to awaken their background knowledge. Then, students were asked to read a text. When reading was completed, the teacher went over the students and addressed any questions or comments from the learners. After completing the text, they received form-focused task. In this task, teachers read a short text containing new words which they need to understand the main idea twice and at a normal speed to students. The students listened very carefully and wrote down as much information as they could as they listened. When the reading was finished, the students were divided into small groups of three and were asked to use their notes in order to reconstruct the text as closely as possible to the original version. Upon the completion of the texts, learners received communicative, pair/group discussion task. At last, they were asked to compare and analyze the different versions they produced. In the second group, there was no focus on meaning trend the teacher taught Wh questions just by explanation, say, in the Grammar Translation Method. Within the focus on form and meaning group, the teacher discussed the topic of the text in order to activate learners’ knowledge. Then, students were given lists of grammatical points along with explanations, and they were asked to memorize the new words. At last, the teacher-made grammar test was administered as the post-test of the learners’ achievement in new words. Altogether, the current study investigated the visible impacts of focus on form and meaning on the learning of Wh-questions on intermediate EFL learners in a high school in Abadan. The participants were 60 male native speakers of Persian and Arabic level of L2 proficiency ranging in age from 15 to 16. In order to have homogeneous groups, the learners were given a grammatical pretest including 25 grammar questions and were assigned into two equal groups based on the results of that exam. In order to state the reliability of this test, the split-half method was utilized and the tests were piloted on a group of eight third year high school students who were not the members of the sample. They were selected from among four classes and divided into two groups of 30, namely experimental and control groups. The focus on form and focus on meaning treatment were taught to experimental group whereas the control group was taught in the normal traditional way without resorting to the intended treatment. Put another way, experimental group was treated by focus on form strategy. During the eight sessions of the treatment, they experienced learning Wh-questions in particular and grammar in general. In simple terms, the fundamental purpose behind the current document was examining the impact of focus on form and meaning on grammar improvement of Iranian EFL learners in general and Wh-questions in particular.

3.5. Data Analysis

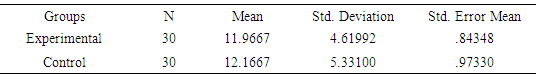

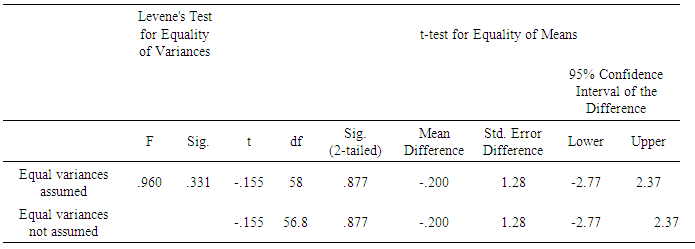

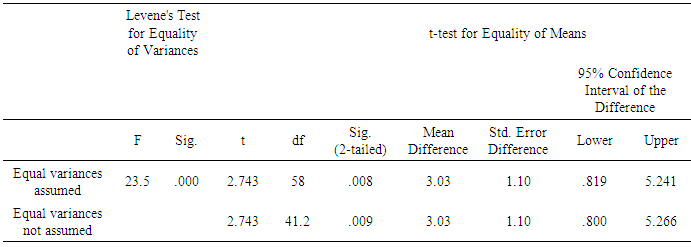

- In order to determine whether focus on form and focus on meaning have any effect on better learning this study is conducted and the collected data were analyzed using different statistical procedures. Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviations were estimated to describe and summarize the data. The statistical analysis of Paired and Independent Samples t-test on the two groups’ pre-test scores indicated that the difference among the means of two groups was not significant. Then a post-test was run examine the potential effect of each group.

4. Results

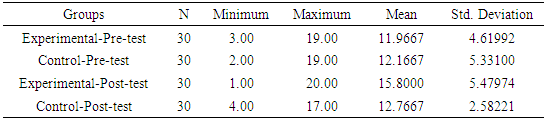

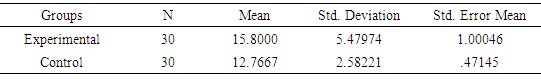

- The results of descriptive statistics are the pre and post-tests are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- This study aimed to investigate the answer to the following research questions. Results showed that the pre and post-tests are different in the results.RQ 1: Does focus on meaning technique affect teaching Wh-questions to Iranian senior high school EFL learners?With regard to the above questions, it should be pointed out that based on the data obtained it is logically claimed that the first research question is positively verified. It comes true that there is difference between interactive focus on meaning and traditional focus on meaning in teaching Wh-questions in Iranian senior high school EFL learners. It means that focus on meaning has positively affected learning Wh-questions by Iranian EFL learners at the first grade at the senior high school. Put another way, focus on meaning can be regarded as a good technique in teaching Wh-questions. We can say that just knowing the rules and memorizing them is insufficient. Here findings revealed that the experimental group (focus on form and meaning) registered a significant improvement. We concluded that both form-based and meaning-based instruction is required. Accuracy, fluency and overall communicative skills are probably best developed through instruction that is primarily meaning-based but in which guidance is provided through timely form-focused activities and correction in context.Ellis (2005) agrees with the results of the study that discovery activities can assist learners to use explicit knowledge to facilitate the acquisition of implicit knowledge. This means there are some theoretical positions that support the view of discovery learning in focus on form. One of them is deep processing, in which learners are involved, the other one is self-investment since learners need to be motivated both instrumentally and integrative and this can be achieved through approaches which excite the curiosity of learners in relation to a language feature. The results of his study are supported by Nassaji and Fotos (2004) who believe that the positive effect of focus on form and meaning trait instruction on students’ post-test was significant compared to the control group. The post-test scores indicated that the focus on form and meaning strategy has been positively gained by the experimental group. The post-test scores of the experimental group indicated that the group had better improvement compared to the control one. Descriptive statistics also showed that the mean scores of the experimental group were greater than that of control group. Therefore, focus on form and focus on meaning instruction had positive effects on enhancing in grammar. The basic question in this study was whether or not focus on form and focus on meaning instruction enhances EFL grammar. The results are straightforward and make a strong argument in favor of considering focus on form and focus on meaning with Iranian EFL learners. The t-test statistics was used to analyze the data collected. There was a significant difference between the performance of experimental students and their counterparts who were not significant. Moreover, focuses on form trend regarding receptive grammar require further investigations. Although a positive correlation with grammar was observed in the current study. Future findings might contribute to a better understanding of the fact that some students benefit more from intervention programs and, therefore, show better treatment outcomes than others. With regard to the limited number of participants and the study setting place for the present study, more research is needed to prove the validity and justifiability of this research. Teachers of English teachers may do the activities: (1) Consider students’ individual differences by using focus on form and focus on meaning trends in order to illustrate the intended grammar, (2) Exchange experiences among teachers by attending each other classes especially in grammar to show benefits of using the above trends in teaching grammar, (3) Select effective methods and techniques which encourage students to use grammar correctly, and (4) Move from the ordinary teaching methods to using such trends in authentic situations. The second research questions deals with the difference between the new approach of focus on the form and forms and the traditional one which just focuses on the form. The discussion is presents in the section.RQ 2: Is there any difference between focus on form and traditional ways in teaching Wh-questions among Iranian senior high school EFL learners?It should be pointed that since focus of form was also a positive factor in learning Wh- questions by Iranian senior high school EFL learners this question was positively answered too. Hence, there was a positive relationship between focus on form and learning Wh- questions by Iranian senior high school EFL learners. Totally speaking, both focus on form and focus of meaning were effective in teaching Wh-questions.The results of this research indicated that learners in focus on forms group achieved significantly higher scores than those in the focus on. These findings showed that using focus on forms tasks were effective in language learning. Moreover, the results of current study confirm Long and Robinson’s (1998) argument that both focus on form and forms instructions are valuable, and should complement rather than exclude each other. Focus on Form instruction, in their view, maintains a balance between the two by calling on teachers and learners to attend to form when necessary, yet within a communicative classroom environment. This means that learning grammar in English through both focus on form and forms enhances a better understanding of the grammatical points. After comparing the two mean scores through t-test calculations, the null hypothesis was justifiably rejected. The results showed that the experimental group demonstrated a more-superior understanding than the counterpart group. The use of focus on form and focus on forms (i.e., structure) strategies to teach Wh-questions also enhanced their attention to grammar. The two groups scored differently on the post-test and difference was statistically significant. The researcher’s interpretation was that focus on form and focus on meaning trend has been proved to be effective and has desirable impact on promoting grammar. The two groups were not significantly different at the beginning of the study. They behaved differently on the post- test; therefore, it seems the focus on form and focus on meaning instruction served the intended purpose than just memorizing the grammar patters or formulas. Therefore, in line with the above mentioned statements and the present study, it could be strongly argued that focus on form activities strategy instruction can significantly influence EFL language learners’ developing grammar. The results of this study are in line with Ellis (2009) who notes that focus on form refers to a method of teaching language typically used for second language acquisition that is meant to be a balance between more extreme approaches. One of the most common methods for teaching language can be referred to as focus on forms, in which an educator teaches parts of speech and words devoid of context. The other extreme from this is an environment in which there is only context and learners focus on meaning rather than on the rules of language. Focus on form is meant to be a middle path that allows language learners to read and learn at their own pace, stopping to shift focus onto rules as appropriate. The focus-on-meaning (FonM) approach to L2 instruct ion corresponds with the no interface view, by providing exposure to rich input and meaningful use of the L2 in context, which is intended to lead to incidental acquisition of the L2. This may be supported by Norris and Ortega (2001) who follow the instructional approach to teach grammar through focus on forms which can be widely found in contemporary English Language classrooms, in techniques such as Krashen and Terrell's (1983) Natural Approach, some content-based ESL instruction and immersion programmers. It supports the results of this study because they found out that focus on form and forms activities led to better learning of Wh-questions.

5.2. Conclusions

- The results of this study showed that focus on forms technique programs are effective in teaching grammar than traditional methods for Iranian EFL learners. The results also showed that the participants in the experimental group has provided with meaningful drills and exercises rather than memorizing formulas. This shows that learning Wh-questions can be enhanced through focusing on meaning since the learners can see the grammatical patterns in a meaningful context rather than in isolated formulas. If research on focus on form and focus on instruction and in the field of second language acquisition, does not takes into consideration the realities of classrooms, then it will bear little relevance to large number of teachers and learners. It seems most likely to meet its instructional objectives in settings in which the following elements are present: principles of CLT are accepted in activities and assessments; classes are sufficiently small enough for teachers to be able to work individually with students and learners individually with their peers; and teachers-and students, are proficient enough in English in order to conduct classes in English and not code-switch when communicative difficulties are encountered.Grammar is the sound, structure, and meaning system of language. All languages have grammar, and each language has its own grammar. People who speak the same language are able to communicate because they intuitively know the grammar system of that language that is the rules of making meaning. Students who are native speakers of English already know English grammar. They recognize the sounds of English words, the meanings of those words, and the different ways of putting words together to make meaningful sentences. Grammar is very important within the English language, since it is, in effect, the glue that holds the language together. With the use of incorrect grammar sentences can become meaningless and their message is unclear. This means that you are not able to communicate effectively and the person who is reading your work may well be quite confused as to your meaning. In effect, grammar is the way in which sentences are structured and the language is formatted, so whilst it may be considered a bit boring to study correct grammar, it really is worth the time and effort. This study provided a reason to claim that focus on form and meaning mode is more effective than traditional mode to master grammar; however, it is strongly recommended to use focus on form in a supplementary manner in order to promote grammar points better and more efficiently. Testing different levels of proficiency may lead to different results. In future, a follow-up analysis of different kinds of focus on form and focus on meaning and a comparative study of them is needed to obtain a better view of their effect on grammar achievement. Future research may also take into account different language groups other than English to see if learners from other language groups may behave similarly. Furthermore, it would also be beneficial to study samples outside of Iran to determine if the same outcome applies not only for non-native English speaking learners but also to children speaking British, Australian and American English or languages other than English.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML