-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2017; 3(3): 64-70

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20170303.02

Using Textual and Demonstration Modalities in Teaching Prepositions to English Language Learners

Bahman Gorjian1, Maryam Kordpoor Kermanshahi2

1Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

2Department of TEFL, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This research was carried out to find out whether using demonstration is effective on Iranian EFL learners’ preposition of movement and position. Sixty female students who studied English in a language institute in Masjed-e- Soleiman in two intact classes. They were divided in two experimental groups, each included 30 participants. A teacher-made pre-test of preposition of position and directions was designed to measure the learners' knowledge at the beginning of the course. The first experimental group received textual modality of preposition phrases instruction while the second group received demonstration activities of prepositional phrases. Textual group was exposed to same min texts and paragraphs including the use of preposition of place, positions and movements and demonstration group received some activities on the use of demonstration, mimes, and showing on the use of preposition in real context. After 12 treatment sessions, the modified pre-test was rearranged in the form of a post- test and it was given both groups. Data were analyzed through Paired and Independent Sample t-test. Results showed that the demonstration group outperformed the textual group. Implications suggest that the EFL learners may learn the prepositions of movement and directions effectively if they receive demonstration and real context.

Keywords: Textual, Demonstration, Preposition of movement

Cite this paper: Bahman Gorjian, Maryam Kordpoor Kermanshahi, Using Textual and Demonstration Modalities in Teaching Prepositions to English Language Learners, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2017, pp. 64-70. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20170303.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A preposition is a word that begins a prepositional phrase and shows the relationship between the noun and another word in the sentence. A preposition must have an object and often indicates a noun’s location. Prepositions can also be used as other parts of speech such as adverbs. To decide how a word is used, say the preposition followed by whom or what. If a noun or a pronoun answers the question, the word is a preposition. Preposition of movements are prepositions that express movement toward something are to, onto, and into (Stuckey, 2012). This study aims to examine the role of the textual and demonstration in learning and retention of preposition and also to investigate the students’ perceptions of their improvement in preposition after the experiment. One of the concerns of the teachers, especially in teaching preposition of movement is how to convey the meanings of them and learners always have problem with understanding the meanings of the prepositions because they have different application. This study amy help both teachers and learners. For teachers, using textual and demonstration develop a new tool for teaching prepositions and facilitate conveying the meaning of the prepositions. For learners, they can facilitate comprehension of the prepositions' meaning (Chodorow, Gamon & Tetreault, 2010).Prepositions are notoriously difficult for English Language Learners to master due to the sheer number of them in the English language and their polysemous nature. Numerous analyses of the linguistic output of English Language Learners have revealed that prepositional errors of substitution, omission, and addition account for the majority of syntactic errors. Since prepositions present such an immense challenge for language learners, it is vital that teachers develop effective instructional methods. In order to determine what pedagogical methods are most effective, it is important to first understand what makes learning prepositions so difficult; this challenge can be attributed to several factors. First, prepositions are generally polysemous. Polysemy is “a semantic characteristic of words that have multiple meanings” (Koffi, 2010, p. 299). Essentially, the majority of prepositions in English have a variety of meanings depending on context. Thus, “learners often become frustrated when trying to determine prepositional meanings and when trying to use them appropriately” (Koffi, 2010, p. 299). Second, as Lam (2009) points out, prepositions can be difficult to recognize, particularly in oral speech, because they typically contain very few syllables. Many English prepositions are monosyllabic, such as on, for, or to. As a result, language learners may not be able to recognize prepositions in rapid, naturally occurring speech. Moreover, the use of prepositions in context varies greatly from one language to another, often causing negative syntactic transfer. The same prepositions can carry vastly different meanings in various languages. For instance, a native speaker of Spanish would have difficulties translating the preposition por into English, since it can be “expressed in English by the prepositions for, through, by, and during” (Lam, 2009, p. 2). Therefore, learners cannot depend on prepositional knowledge from their first language. If learners do make “assumptions of semantic equivalence between the first and second languages”, it often results in prepositional errors (Lam, 2009, p. 3). “Lastly, the sheer number of prepositions in the English language also contributes to their difficulty. English has 60 to 70 prepositions; a higher number than most other languages” (Koffi, 2010, p. 297). “As a result, it is nearly impossible for language learners to systemize English prepositions” (Catalan, 1996, p. 171).

1.1. Approaches to Teach Prepositions

- The traditional method of teaching prepositions is through explicit grammar instruction. Students focus on learning prepositions individually within context, with no further expansion (Lam, 2009). This approach assumes that there is no predictability in the use of prepositions, and that they must simply be learned context by context (Lam, 2009). Lam’s (2009) study revealed that students who were taught using this traditional method had little confidence in their ability to properly use prepositions, and had minimal retention rates. As Lam (2009) elaborates, “trying to remember a list of individual, unrelated uses is hardly conducive to increasing learners’ understanding of how the prepositions are actually used and why the same preposition can express a wide range of meanings” (p. 3). Thus, it is apparent that language instructors must explore more explanatory methods of teaching prepositions.Collocation is one of traditional method in teaching prepositions. Instead of teaching prepositions individually, students can be taught using “chunks,” or words that often occur together. Throughout various studies, the terms “chunk,” “formulaic sequence,” “word co-occurrence (WCO),” and “collocation” are used interchangeably. In the case of prepositions, many of these “chunks” are phrasal verbs. For example, instead of teaching on as a single entity, students can be taught the phrasal verbs to rely on, to wait on, to walk on, to work on, or to pick on. In addition to phrasal verbs, prepositional phrases can also be taught as formulaic sequences, such as on time, on schedule, on…screen, or on…leg (Mueller, 2011).Both Lindstromberg (1996) and Lam (2009) argue that teaching prepositions in an explanatory, semantically-based manner allows for deeper learning, increased learner confidence, and longer rates of retention. This approach claims that prepositions have multiple meanings, but one meaning is thought to be the most dominant, or prototypical. In the case of prepositions, the spatial, physical meaning is considered to be the prototype. For example, the preposition on has multiple meanings, but the prototypical definition is “contact of an object with a line of surface” (Lindstromberg, 2001). The prototype theory contends that the polysemous nature of prepositions can be explained through analysis of the prototypical meaning; all non-prototypical meanings are thought to be related to the prototype, often through metaphorical extension. Looking again at the preposition on, Lindstromberg (1996) explains that non-prototypical meanings like come on can be understood by extending the prototypical meaning. This means that teachers must first teach the prototypical meaning, often through the use of Total Physical Response (TPR), and only then begin to branch out to more abstract meanings. To extend the semantic mapping even further, comparison and contrast to other prepositions can be useful. Lindstromberg (1996), for example, explained the concept of come on by contrasting it with come back. Not only do semantic-based approaches unify various meanings of each preposition, but they also provide connections between prepositions that are otherwise considered only individually.

1.2. Statement of the Problem

- In the current teaching methods little work has been done on preposition. Teachers often find prepositions hard to teach. Sometimes when they want to explain a preposition they use one or two other prepositions to give the definition. So they have to give the definitions of the other prepositions used. The mentioned situation is not only confusing for teachers but also for the students, who find themselves in a “pool” of prepositions with still vague meanings. Many English course books have just a general overview of prepositions and do not provide specific rules on their usage. So most of the time important aspects of the acquisition of prepositions are not mentioned at all, such as when a certain preposition has more than one meaning depending on the context it is used in. The aim of the present study is to identify the needs of English teachers and the difficulties they face while they teach or explain English prepositions. It stresses the importance of using textual and demonstration in learning and retention of preposition of movement. Because prepositions are ploysmouse and they have more than one meaning they are always problematic for students.

2. Literature Review

2.1. English Language Prepositions

- For several reasons prepositions are difficult for the English Language Learner (ELL). First, as mentioned earlier, because each language has its own set of rules, there are clash points when learning a second language (James, 2007; Jie, 2008). Prepositions are at the heart of one of these clash points. These positional words usually come before the noun in English, but in some languages they come after, making them postpositions. In addition, Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) point out that the work of prepositions is often completed through the use of inflections in other languages. Therefore, grammatically, prepositions do not behave in the same way for each language. Second, there is a mismatch problem between English and other languages. Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvick (1985) note that “In the most general terms, a preposition expresses a relation between two entities, one being that represented by the prepositional complement, the other by another part of the sentence” (p.657). Prepositions may express various relationships between words or phrases in sentences. The relationships include those of time, space and various degrees of mental and emotional attitudes.According to (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999) usually when one is learning a second language, he or she will try to define an English word by its native equivalent. Therefore, Spanish will define chair as silla and table as mesa. This method works very well for content words, but is insufficient for function words. As a Spanish learner, I once tried to find a single translation for at. However, after translating only a few sentences, it was clear that at could not be translated so simply. For example, the sentence “I’ll meet you at the bus stop” would be translated “Encontraremosal paradero de autobus” with a standing for at. Yet the sentence “She is at the house” would not be translated using the word a, but the word en: “Ella estáenla casa.” Furthermore, these examples are comparing two closely related languages. The disconnection between languages would be magnified if English were compared to a Slavik or even Asian language. In addition, these are only location words.Temporal words, those involving time, have a similar problem. “He’ll be there at 4:00” would be translated “Élestaráallía las 4:00” using the word aagain. Yet “They’ll see each other at Christmas” would be translated using en: “Los veránen Navidad.” It must be understood that while atmay be the same word, it has two different meanings in this situation: one meaning in space, and one in time. These two thoughts would be expressed four different ways in Spanish, two for space and two for time. So a Hispanic learning English must learn how to funnel his or her thoughts from four different meanings into two different meanings.Third, not only is there a mismatch problem between languages, but there is a perceived inconsistency in English itself (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999; Evans & Tyler, 2005). Certain prepositions can be applied in one form, but not another. For example, class can meet on Tuesday at 7:40, but it cannot meet at Tuesday on 7:40. Additionally, one could leave out the preposition on from this phrase, but could not omit at (class will meet Tuesday at 7:40). Similarly, I can meet you in but not on the house, while I can meet you on the corner, but not in it. Notice with these spatial examples, if you do tell someone you will meet him or her on the house; he or she will expect to find you on the roof. If you tell someone to meet you in the corner, he or she might assume you are in time-out in the corner of a room. The language learner will not understand why the temporal prepositions can only be used with certain words. Nor will the ELL understand why changing the spatial preposition will change the meaning of the whole phrase. In addition, a student might question why changing the temporal preposition will make the sentence grammatically incorrect, but changing the spatial preposition changes the meaning. In truth, the native English speaker does not know the answer to these questions either. The native simply hears the incorrect sentence and thinks it sounds wrong. Finally, the most frustrating challenge to prepositions is how they are taught, or rather, how they are not taught. Textbooks such a Grammar Sense by Susan Bland, North Star: Reading and Writing by Laurie Barton and Carolyn Sardinas, How English Works by Ann Raimes, (1990) Grammar Dimensions 2 by Heidi Riggenbach and Virginia Samuda, Grammar Dimensions 3 by Stephen Thewlis, and Interactions by Werner and Nelson (2007) do not mention prepositions in any way, and therefore do not facilitate the teaching of them. Other textbooks such as Grammar Links by Linda Butler, Grammar in Context by Elbauman Pemán, and Grammar Troublespotsby Raimes (1990) only teach prepositions at certain levels and teach spatial and temporal uses separately from each other. In Basic Grammar in Use by Murphy and Mosaic by Werner and Nelson (2007), prepositions are used in conjunction with other grammatical units or are displayed, but they are not actually explained in any detail. When prepositions are taught in the text, they are usually allotted a page or less. With no textbook to rely on, the teacher often encourages the student simply to memorize the prepositions (Evans & Tyler, 2005). However, it has already been demonstrated that prepositions cannot be simply translated. Also, their seemingly haphazard nature prevents any easy memory tool. Thus the student is left to memorizing hundreds of different phrases, all of them containing prepositions.

2.2. Prepositions of Direction and Position

- Preposition that indicates physical relationship is preposition of direction. It usually deals with movement, to show the direction where the movement would go. They are: (1) From-to, from refers to the place where the movement starts and to or toward refers to the place where the movement stops, for instance, My father walks from home to his office. (2) Into-out of, into expresses the direction to the inside, for instance, The blind man bumped into me. Meanwhile, out of expresses to the outside, for instance, The teacher is walking out of the classroom. (3) Up-down, up expresses the motion or direction from a lower position to a higher one, while down in contrast with up in term of vertical direction. For example: He climbed up/down the stairs. (4) Around: it expresses movement in a circle direction, for instance, The ship sailed around the island. (5) Across, through, past: these prepositions express the motion from outside to another in term of a horizontal surface. For example: You can drive through that town in an hour. He walked past the house. He lives across the street (Miftahudin, 2011). Based on the explanation given above, it can be seen that there are many types of preposition with different function. They indicate certain things; one preposition sometimes cannot be used to replace the other preposition. In conclusion, though preposition is regarded as a simple structure, but in fact, it is much more complex if it is applied into sentence in context (Barrett & Chen, 2011). One preposition can be functioned differently (Frank, 1972).Prepositions have several types based on its functions. However, in general, preposition has a function of connecting a noun or pronoun to another word, usually a noun, a verb or an adjective.Examples:The girl with red hair is beautiful.They arrived in the morning.She is fond of roses.After a word of motion a preposition of position or direction; may be used without a noun object. Such a prepositional form is usually classified as an adverb. For example, in the sentence: He fell down the stairs. “Down” is functioned as a preposition when it governs a noun or pronoun. Meanwhile in the sentence: He fell down. “Down” in this sentence is functioned as an adverb when it merely modifies a verb and does not show relationship between words. In the spoken language, these two prepositional forms are stressed differently. For example:He fell down the stairs (i.e.g Down as preposition is unstressed).He fell down (i.e.g Down as an adverb is stressed). (Miftahudin, 2011).This section has reviewed the theatrical and empirical studies on the preposition of directions and movements. There are lots of methods in language teaching in general and teaching prepositions in particular. Using demonstration can motivate the EFL learners to learn and learn more eagerly since they may like innovation in learning in contrast with traditional old methods of learning. In the next section methodology, participants, instruments and procedures are going to be discussed. The research question asks: Does using textual or demonstration modalities have any significant effect on the learning of the prepositions of movement among Iranian EFL pre-intermediate learners?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

- The participants of this study were 60 female students who were selected in two intact classes. They were within the age ranging from 14 to 16 and they are studying English at Kimia language Institute in Masjed-e-Soleiman. They were divided in two experimental groups. The first experimental group (n= 30) and second experimental group (n=30) as the textual and demonstration groups who participated in the treatment sessions. Textual group was exposed to proposition of movement through the textual and the other group was exposed to the demonstration in teaching. The use of the preposition in either the textual class or the demonstration class was taught by the researcher.Before commencing the experiment, the textual and experimental groups were aware about the study so as to minimize any misunderstanding pertained to the study throughout the research. In order to increase the validity and avoid any cultural and social differences all of the participants were chosen from the same institute.

3.2. Instrumentations and Materials

- The instrumentations in this study included a teacher made pre-test of prepositions of movement and position. This pre-test was designed from the units of the book entitled as “Connect 1”. It included 50 multiple-items and its reliability index was assured through a pilot study and estimated through KR-21formula as (r=.691). English prepositions of movement was selected from students’ textbook, this pre-test was used at the beginning of the study. The allotted time to respond was 40 minutes. This pre-test was carried out by the students a week before the treatment sessions.The post-test which was designed based on the modified pre-test (Multiple choice-formats). It included English prepositions of movement and it was given to the experimental groups at the end of the semester. It included English preposition of positions and movement items which the students were asked to answer. This test consisted of 50 items, hence it was scored out of 50. The post-test was as the same as the format of the pre-test but it was displayed in a different order items to avoid reminding the items. The reliability of the posttest was calculated through a pilot study which was estimated through KR-21 formula as (r=.801). Validity is arguably the most important criteria for the quality of a test. The term validity refers to whether or not the test measures what it claims to measure. On a test with high validity the items were closely linked to the test's intended focus. There are several ways to estimate the validity of a test, in this study the researcher used some of the experienced teacher’s point of view in order to gain the face and content validity of the test.

3.3. Procedure

- Sixty students who studied English in a language Institute in Masjed-e- Soleiman were selected in two intact classes. They were divided in two experimental groups, each included 30 participants. A teacher-made pre-test of preposition of position and directions was designed to measure the learners' knowledge at the beginning of the course. The first experimental group received textual modality of preposition phrases instruction while the second group received demonstration activities of prepositional phrases. Textual group was exposed to same min texts and paragraphs including the use of preposition of place, positions and movements through repetition, using in text and different sentences and demonstration group received some activities on the use of demonstration, mimes, and showing through demonstration, action, gestures and pictures on the use of preposition in real context. For example in order to teach toward teacher do it by walking toward whiteboard. After 12 treatment sessions, the modified pre-test was rearranged in the form of a post- test and it was given both groups and compared the obtained results of two groups’ post-test.

3.4. Data Analysis

- Data were collected through a pre- and posttest in order to answer the research questions. The results of both tests were analyzed through using the SPSS program, version17. First, the data of the pre-test for each group were analyzed in order to find the mean and standard deviation of the scores of each group. The same procedure was used for the posttest. Independent Samples t-test were employed to see if there were significant differences between the two experimental groups. The hypotheses were tested at a .05 level of significance.

4. Results

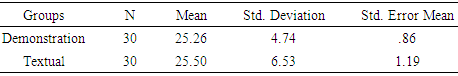

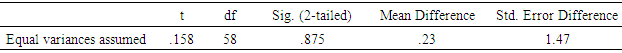

- The scores were obtained from the pre-test of English preposition for both groups of the textual and the demonstration were compared and analyzed statistically. The means and standard deviations for the pre-test scores are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

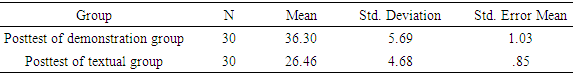

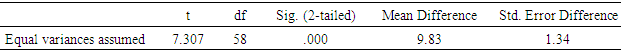

- In this study, the researcher compares the two strategies of teaching of prepositions of position and movement. The two research questions addressed in this study intended to investigate the role demonstration and textual modalities in learning prepositions of directions and movement. First we discuss the first research question. RQ1. Does using textual or demonstration modalities have any significant effect on the learning of the prepositions of movement among Iranian EFL pre-intermediate learners?The researcher has shown that the instruction through the demonstration modality had an advantage over the textual modality, since the students in the demonstration group out performed those participants in the textual group. These findings showed that the demonstration group seemed to have higher score which were highly significant. After analyzing the data through descriptive statistics and applying an Independent Samples t-test on the demonstration and textual groups’ performance, the results revealed that the demonstration group outperformed the textual group in learning preposition of movement. Therefore, it can be said that the training program based on the demonstration activities could have positive effects on the demonstration groups’ performance the preposition of movement and position. Few studies have emphasized the role of demonstration modality in learning preposition in second language learning. The results of the study are in line with the following studies:Deese, Ramsey, Walczyk and Eddy (2000) support the results at present study. They noted the effectiveness of the demonstration modality was studied using two classes enrolled in a chemistry class for engineering majors. Both classes were given an end-of-course conceptual assessment and a pre- and post-attitude survey. There was no significant difference in attitude between the individual pre- and post-survey for either group or when the groups were compared. However, the treatment group did show a significantly greater conceptual understanding at the end of the course than did the control group. This seems to indicate that the demonstration assessment can be successful at improving student retention.Miftahudin (2011) also supports the finding of the present study who conducted a study which attempts to examine the use of songs in enhancing students’ mastery of prepositions. It is in contrast with the use of conventional method for teaching prepositions. The study found the effectiveness of using songs in in teaching preposition because after treatment experimental group outperformed the control group.In a more recent study, the effectiveness of demonstrations was revisited in the Saudi Arabian school system (Harty & Al-Faled, 1983). This study support the findings of present research. Two classes were used to compare the lecture/demonstration to the lecture/laboratory styles of instruction. The achievement test was administered before the study and immediately after the study. Results indicated that demonstrations are beneficial when a laboratory experience is not an option, such as when sufficient funds are not available. The results are also agrees with Lam (2009) who worked on the role of demonstration in teaching grammar.According to Evans and Tyler (2005), when prepositions are taught in the text, they are usually allotted a page or less. With no demonstration to rely on, the teacher often encourages the student simply to memorize the prepositions. However, it has already been confirmed that prepositions cannot be simply translated. Also, their seemingly haphazard nature prevents any easy memory tool. Thus the student is left to memorizing hundreds of different phrases, all of them containing prepositions. The results of this also confirmed the idea from Lam (2009) who noted that the traditional method of teaching prepositions is done through explicit grammar instruction. Students focus on learning prepositions individually within context, with no further expansion (Lam, 2009,). This approach assumes that there is no predictability in the use of prepositions, and that they must simply be learned context by context (Lam, 2009). Lam’s (2009) study revealed that students who were taught using this traditional method had little confidence in their ability to properly use prepositions, and had minimal retention rates.The results showed that there was a significant difference between the two means at the level of 0.05. Therefore, it can be concluded that participants of the demonstration group improved to a greater extent due to the treatment they received. Therefore, results showed that demonstration activities effectively improved participants’ learning English preposition of movement and position.

5.2. Conclusions

- The present study was designed to determine the effect of demonstration and textual activities on the learning of the preposition of movement among pre-intermediate students. The results of this investigation are in line with Bruce, Ross, Flynn and McPherson (2010) who showed that using demonstration activities in teaching preposition of movement and position can improve students' knowledge of preposition. This study has shown that the application of demonstration activities in EFL context can improve pre-intermediate learners’ knowledge of preposition. When mastering a language, demonstrations are very important in gaining language knowledge. Demonstrations may help to make the language useful in the classroom, more realistic and alive; it helps maintain the student’s attention and makes the class more interesting. The results of this study are supported by & Chen (2011) who note that the demonstration activity can be used at any stage of a lesson. These activities are easy ways of bringing the outside world into the classroom since Prepositions are ‘little words’ but they carry a lot of meanings. It is important to choose the right preposition or you may say the wrong thing. If teacher want to teach young learners how to use prepositions, the demonstration aids will help the EFL learners aware of the intricacies of, which they usually take for granted. This awareness will certainly make to use demonstration more instructively. Awareness of using demonstration will also encourage teachers to develop their professionalism which is in line with Mahmoodzadeh, (2012). Thus, they are expected to use kind of in the classroom, to motivate learners. All these professional qualities can be fostered by the positive use on demonstration. Understanding the fact that using demonstration can help to polysmouse nature of preposition because, it show the different application of preposition in different situation directly. People in charge of training future EFL teachers can also benefit from this study and its findings. Teacher trainers are also invited to make their trainees aware of the importance of using demonstration in the EFL classroom. Not only that, but trainees should be encouraged to conduct research in this field to prepare themselves for their future carrier.There are some suggestions for those interested in learning teaching prepositions. The use of demonstration activities could contribute significantly to the improvement of the students’ English preposition mastery, and then it is suggested to be applied by the teacher in English classes. Eager researchers can investigate the role of gender in learning preposition. Another suggestion for further researchers is to investigate the effect of using demonstration on preposition learning of participants with different English proficiency levels. The role of demonstration in the other skills of language learning like, speaking, listening and teaching different elements of grammar can be investigated.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML