-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2017; 3(2): 33-40

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20170302.01

The Effect of Pedagogical Films on the Development of Listening Skill among Iranian EFL Female and Male Learners

Mona Dehghan1, Bahman Gorjian2

1Department of TEFL, Bousher Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bousher, Iran

2Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of TEFL, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The present study aimed at exploring the possible effect of pedagogical films on the improvement of listening skills of Iranian EFL female and male learners. The study specifically investigated whether pedagogical films could be regarded as an improvement means in language education. In this regard, fifty EFL learners from Pouyandegan Language Institute in Abadan were selected. Learners were randomly divided into experimental (N=25) and control (N=25) groups. The experimental group watched pedagogical films while control ones listened to audio CDs of those films. Interchange Objective Placement Test was administrated as pre- and post-test to check the possible listening improvement between and among the groups. After collecting data, independent and paired sample t-tests were run to analyze data. The findings of the study revealed that experimental learners significantly outperformed as compared with control groups in their listening achievements. However, there were no significant differences between female and male learners’ listening skills. The findings of the study suggest that using the pedagogical films can promote EFL learners’ language ability of listening skills.

Keywords: Listening skills, Pedagogical films, Listening improvement, Gender, Language learning

Cite this paper: Mona Dehghan, Bahman Gorjian, The Effect of Pedagogical Films on the Development of Listening Skill among Iranian EFL Female and Male Learners, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2017, pp. 33-40. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20170302.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Listening is a complex cognitive process which entails the ability to correctly receive and interpret intended meaning hidden in the communication process. Listening is the centerpiece of learners’ interactions without which learners could not understand the message. According to Vandergrift (2005), listening skills is highly challenging as it greatly depends on learners’ knowledge of linguistic, socio-cultural and contextual features in order to understand and interpret the meaning conveyed. With regard to the role of listening in important standardized examination e.g. TOEFL, IELTS, Renandya (2012) pointed out that listening ability importantly functions in language proficiency and attainment in comparison with speaking, reading and writing skills. According to Canning-Wilson (2000), use of illustrations, visuals, pictures, mental images, figures, cartoons, charts, graphs, colors, and some other things help learners to clarify the messages and enhance understanding. Visual imaging systems have widespread among people and is an inseparable part of people’s lives (Progosh, 1996). Nowadays, exposing students to English culture is the best way to study English. Using original movies is one of the best approaches because language in movies is rich and dialogues are authentic (Canning-Wilson, 2000). In a video, messages can convey by gesture, eye contact, and facial expression. It creates a situation that can lead to predicting information, enhancing clarity, and understanding stress patterns. Also, teachers can ask both display and referential questions via videos (Canning-Wilson, 2000). Based on the finding, it is easy to understand that the scenes if they are accompanied by actions or body language can be an effective tool in enhancing the comprehension of learners (Baltova, 1994).Visual cues using in videos are informative and enhance comprehension in general, but do not necessarily stimulate the understanding of a text (Baltova, 1994). It is also suggested that teachers had better introduce some background knowledge information before listening. In this way, explaining the names of countries, places or people are effective (Lingzhu & Yuanyuan, 2010). Tatsuki (1998) discovered that when learners hear something incorrectly or see unexpected behaviors or see a scene with full of information, they panic and comprehension breakdown is occurred. Comprehension of the learning process leads to success in learning language (Goh, 2000). Tatsuki discovered learners stop films and repeat certain passages because they don’t understand them or they felt lost some parts of the films. He maintains "Slip of the ear" seems is one of the sources of breakdown. "Slip of the ear is when you mishear what is said for a number of reasons (inattention, preoccupation with another topic, sound distortion) and the mishearing leads to either misunderstanding or incomprehension". He suggested "Provide contextualized help", "Pre-teach foreign words", "technical language", "idioms and colloquialisms", "Sensitize learners to varieties of spoken English", and "Encourage observation of the situation and other contextual cues that may assist comprehension" to deal with comprehension hot spots. Additionally, different techniques such as description or note taking can be used during listening tasks in order that learners can discover the meaning and understand listening tasks. Lingzhu and Yuanyuan (2010) discovered that some films lack necessary pauses and repetitions which interfered with listening comprehension and learning, hence students may use note taking to understand them.Regarding the impeccable role of media in language learning, however, very little research has discovered the effects of pedagogical films on listening. The present study aims to investigate the role of pedagogical films in developing learners’ listening skills.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- In many EFL classes, even where teachers have devoted much time to teaching listening, the results have been disappointing. Nowadays using traditional approaches such as using textbooks seem boring. Therefore, finding a new way to alleviate this problem and help teachers with listening instruction seems to be crucial. Usage of pedagogical films in teaching listening has been suggested as a teaching method. The present study will show the effects of pedagogical films on listening.

1.2. Significance of the Study

- Nowadays, using pedagogical films, as audio-visual aids, has taken into consideration in teaching EFL/ESL. This research seeks to do a comparative study to see the effects of pedagogical films on listening. This goal can be achieved through the usage of pedagogical films in classrooms. Study in this area is essential for both teachers and students because it will indicate the values of films in EFL classrooms. The results of this study will give teachers good insights about using pedagogical films in classrooms. The results will be further significant for language learners to use the strategy.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Listening

- Listening skills play a significant role in language education. Since 1970s, Feyten (1991) asserted, listening skills has been regarded as a contributing factor in promoting learning and developing learners’ language acquisition. Besides education, it goes without saying that listening plays an important role in communication as it is the first language skill children acquire. It might not be surprise to point out that language learning depends on listening skills inasmuch as through listening, learners will receive the aural input which helps them in language acquisition. Feyten (1991) highlighted that during communication, 45% of time is spent on listening, 30% on speaking, 16% on reading, and 9% on writing. It can be inferred that second and foreign language acquisition to a great extent rest on listening comprehension. Feyten (1991) further argued that, out of allotted time for listening, however, the effective listening is almost 25%. Listening is the means which provides learners with the opportunity to gain a large portion of their education, their information, their understanding of the world, their ideals, sense of values, and their appreciation. Galvin and Terrell (2001) specifically defined listening as “an active process that includes receiving, interpreting, evaluating and responding to a message. It takes effort and concentration” (p. 110). According to this definition, listening skills is a challenging skill which mainly concentrates on receiving meaning. Rost (2002, cited in Vandergrift, 2005, pp. 1-2) stated that listening skills is “a process of receiving what the speaker actually says (receptive orientation); negotiating meaning with the speaker and responding (collaborative orientation); and, creating meaning through involvement, interpretation and empathy (transformative orientation)”.Accordingly, listening skills is a high frequent skill with complex processes which is overshadowed by physiological process, pays attention to selected stimuli, assigns meaning to the input and stores and repossesses information. It is also essential in developing fluency or mastery, L2 learning, and other three language skills (Rost, 2007; Vandergrift, 2005). During listening process, listeners attempt to take information and retrieve them for more interaction. Smith (1995) pointed out that listening has four elements including attentive, appreciative, analytic and marginal. Attentive component is the one that students require to construct skills in all other fields (Smith, 1995). As such, listening process happens in mind to the purpose of grasping the intended meaning. During this process, however, learners barely have a second opportunity to listen to the same text. Listening is affected by the nature of the acoustic input, stress, intonation, and memory capacity. Mainly, the element which creates the most difficulty is too many new and unfamiliar words. When students listen to input, they should identify words by hearing them and are required to understand them very swiftly. There is no second opportunity for listening; speakers keep on speaking and listeners must follow the interlocutors. There is no time to think. Moreover, worry, fear, semantics, language differences, and noise are among other blocks to listen successfully. In this respect, Underwood (1989) stated, “although the problems are many and various, they are not all experienced by all students, nor are they experienced to the same degree by students from different backgrounds” (p. 16). It should be highlighted that listening is not only a cognitive process but also includes linguistic and non-linguistic knowledge. In the listening process, learners receive input; explain them in terms of linguistic and nonlinguistic knowledge. With respect to linguistic, listeners pay attention to components of language as vocabulary, phonology, syntax, semantics, and discourse of the input. Similarly, learners concentrate on non-linguistic knowledge including the topic, the context and how that knowledge applies to the incoming sounds (Feyten, 1991). To make it simple, learners are exposed to aural input, use prior knowledge, and pay attention to the context to construct mental representations of meaning (Liu, 2009). It should be expressed that listening skills “takes place within the mind of the listener, and the context of interpretation is the cognitive environment of the listener” (Buck, 2001, p. 29). Accordingly, language learners, particularly EFL ones, experience difficulties in developing listening skills inasmuch as they are provided with a limited amount of exposure to English in their daily lives, specifically when learning academic English (Buck, 2001).In another attempt, Anderson (1995) tried to provide a more comprehensive model. As it is mentioned above, listening is a complex process, connecting acoustic input, vocabulary knowledge, linguistic knowledge, and background knowledge. Exploring listening at a deeper level, it incorporates processes as decoding input and stemming meaning from aural input. In this respect, Anderson presented a three-phase language comprehension model, perception, parsing, and utilization. Phases in Anderson’s level have communality with each other and necessitate three levels of processing. Phases include perceptual processing (segmenting phonemes), parsing (segmenting words), and utilization (using long-term information sources to explain the meaning).

2.2. Multimedia and Education

- Students at all proficiency levels can benefit from the use of films, since the speech rates can be found at different speed which matches learners’ level (Talavan, 2007). According to Ardriyati (2010), if films show interesting and authentic scenarios in which relevant English is applied they can be valuable instructional means. Chung (1999) argued that most language instructors should know that exposure to authentic materials through video helps language learning. Salaberry (2001) asserted that films in general and video programs in particular provide an inexpensive as well as a versatile, pedagogical tool. Ellis (1993) pointed out that authentic texts can increase the intrinsic interest of the students as a result of different kinds of practices. The students’ participation in L2 use assists them become integratively motivated and as a result decreases affective filters (Mishan, 2005). As it is mentioned above, films can be valuable classroom means if they provide interesting, and authentic scenarios in which English is applied. However, instructors should consider some points in playing films to take learners’ attention. Learners enjoy films that are pleasing and short, have attractive characters, show useful information, and deal with relevant social topics. Teachers are required to choose movies that utilize suitable and level- appropriate language (Ardriyati, 2010). Besides, King (2002) argued that age and culture of both genders are important elements in choosing films.Assessing the effect of narrow listening, Dupuy (1999) stated that uncontrolled casual conversations are too difficult for beginning and intermediate foreign language students to comprehend. Dupuy asserts that “the repeated listening of several brief tape-recorded interviews of proficient speakers discussing a topic both familiar and interesting to the acquirers offers them a valuable and rewarding alternative” (p. 351). Set up to evaluate, he ran a study working on EFL beginning and intermediate college students' reactions to narrow listening and its effect on their language development. Findings revealed that narrow listening was useful in promoting listening comprehension, fluency, and vocabulary, and in increasing learners’ confidence with French.

2.3. Research Questions

- Following the objectives of the study, following research questions were stated:RQ1. Do pedagogical films affect Iranian EFL learners’ development of listening skill?RQ2. Do pedagogical films affect the listening skill of female and male learners?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

- The population of the study was 70 learners who were studying English at Pooyandegan Institute in Abadan. They were selected based on non-random convenient sampling method since they were the learners the researcher had access to. Then they took Nelson English language proficiency test, intermediate level that was designed by Fowler and Coe (1976) to check their homogeneity. Fifty learners whose scores were one standard deviation (SD) above and one SD below the mean were selected as the research sample of the study. They were non-randomly divided in two groups of experimental and control, each included 25 participants.

3.2. Instrumentation

- The main purpose of this study was to explore the possible effect of pedagogical films on the listening development of Iranian EFL learners. In this respect, two instruments were applied in this study. A thorough explanation of the instrument was presented below.1. Nelson English Language Proficiency TestBefore the study, learners were tested for homogeneity of proficiency level in English language. In this respect, Nelson English language test: Intermediate level (Fowler & Coe, 1976) was applied and administrated among learners. The test contained 50 items: 14 cloze and thirty-six structure items. The learners were supposed to answer them in 60 minutes. The analysis of results indicated that all learners enjoyed same level of proficiency. Accordingly, learners were non-randomly divided to two groups of experimental and control.2. Interchange Objective Placement Test: Intermediate LevelTo delve learners’ listening performances, Interchange Objective Placement Test: Intermediate Level (Lesley, Hansen & Zukowski-Faust, 2005) was applied. The test contained 70 multiple-choice items which chiefly evaluates students’ receptive skills (listening, reading, and grammar). The test consists of three sections: Listening (20 items), Reading comprehension (20 items), and Language Use (30 items). 20 items of listening were applied in this study. The listening items assess learners’ ability to learn the main idea, context, and supporting information in a conversation, as well as the interlocutors' intention. According to Lesley et al. (2005, p. 5), "the different components of the test may be administered to individuals or to groups, and in any order". For the purpose of this study, the test once was administrated as pre-test before implementing the treatment and once more after the intervention to check he possible effect of pedagogical films on learners’ listening skill. Learners were asked to listen to the audio tracks and selected the option that they thought it was the correct one. The Cronbach alpha of the listening test was calculated as 0.85.

3.3. Materials

- As the materials of the teaching, the researcher focused on the available pedagogical films applied in context of Iran. The selection was based on some important criteria:• Vocabulary frequency and unfamiliarity• Existence of the variety in film’s subjects• Participant’s social and religious norms and values• Participants' proficiency levels• The relatedness of the film to the students’ daily life in order to communicate well with them Accordingly, films from Top Notch 3 A and B were designed at the intermediate level were chosen for the experimental group and the audio CDs were used for the control group. These Top Notch films were pedagogical and suitable for employing in classes to discover their effect on learners’ listening skills. Based on class schedule, the teacher selected 8 episodes of topnotch film. Every episode was about 3 to 5 minutes. Time of discussing on films or dealing with audio CDs lasted 45 minutes in each session. In every session, the instructor used one episode for each class.

3.4. Procedure

- This study is a quasi-experimental study which explores the possible effect of applying pedagogical films on learners’ listening attainments. In this respect, 50 EFL learners participated in this study. After checking the language homogeneity of learners, they were divided into experimental (N=25) and control (N=25) groups. Before the intervention, learners took a pre-test to further analyze their performances after the intervention. The intervention phase started. The experimental group watched pedagogical films while control ones listened to audio CDs of those films.The treatment lasted ten sessions, 45 minutes a session, once a week. During the treatment, in each session, the instructor devoted the time to watching the movie, practicing new words, and talking about that part of the movie. Each movie was presented to the learners for 15 minutes in every session. Then, the instructor worked on that part of the movie. Learners were also suggested to used note taking, question and answer, discussion, and description to better understand movies. In this regard, learners took notes while they watched the film for reviewing it. After watching the film some questions were asked to find out learners’ understanding of it and then they described it. Moreover, the learners discussed the movie and gave their opinion about the plot of the film. On the other hand, learners in control group followed the same activities which were done in experimental group. The only difference between both groups related to using audio CDs of the pedagogical films instead of pedagogical films in control group. For example, learners in control group toke notes while they listened to the Top Notch A and B audio CDs. After implementing the intervention and working on films and CDs, learners participated in a post-test of listening skill. The results of pre- and post-test, as a result collected for further analysis.

3.5. Data Analysis

- The present study intends to investigate the effects of using pedagogical films on the development of listening skills of Iranian learners. Moreover, the study will probe whether gender can be an effect variable in differing learners’ performances. After collecting data, a series of analysis were conducted to evaluate the possible effects:• An independent sample t-test to check the homogeneity of learners before the intervention• A paired sample t-test to check the possible effect of pedagogical films on learners’ listening skills• An independent sample t-test to check the possible differences between experimental and control groups• An independent sample t-test to check the possible differences between female and male learners with respect to their listening attainments

4. Results

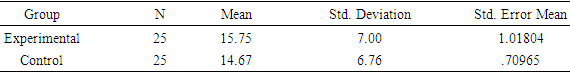

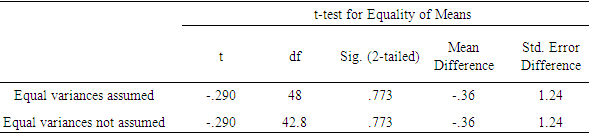

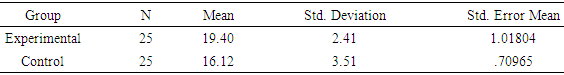

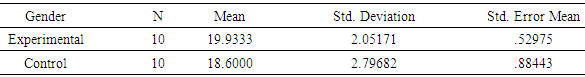

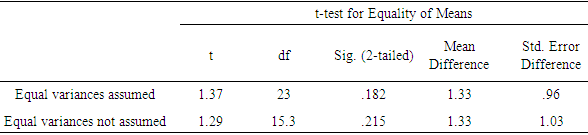

- The present study intended to investigate the effects of using pedagogical films on the development of listening skills of Iranian learners. In other words, the researcher attempted to have a deep look at how pedagogical films can improve learners’ comprehension. In this respect, after homogenizing learners, they were randomly divided to two groups: experimental ad control groups. Learners in experimental group watched movies and worked on episodes of films. However, learners in control group listened to the audio CDs and worked on them. Pre- and post-tests were administrated before and after the intervention. The data were collected for further analysis. Descriptive statistics is presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

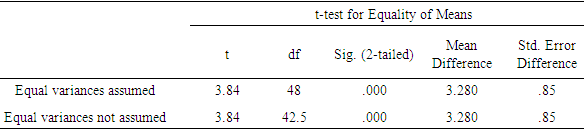

- This study is a quasi-experimental study which explored the possible effect of applying pedagogical films on learners’ listening attainments. The gender was another variable of the study. Pre and post-tests were administrated among learners to know how media affect their listening participation. The data were collected and analyzed. The statistical findings were reported above. In the following, a discussion on the findings of study with reference to previous studies was presented. The first research question of the study delved: Whether pedagogical films affect Iranian EFL learners’ development of listening skillTo this end, learners were undertaken a treatment and pre- and post-test were administrated. According to the findings, there are statistical significant differences before and after the intervention in experimental learners’ listening attainments. It denotes that, pedagogical tools are significant instructional means which effectively promote learners’ listening skills. Findings of the study further proved that there is a meaningful difference between listening skills of experimental and control groups after the intervention. The results highlight the importance of multimedia in language acquisition, promotion of learning skills and strengthen of cognitive abilities. The literature has also reported the same significant effect of multimedia on learners’ language functioning. In their study, Bahrani and Soltani (2011) explored the effect of films on improving speaking ability of the learners. Findings of the study highlighted a significant improvement in favour of experimental learners. The study has also revealed that learners’ vocabulary knowledge and communication skills have noteworthy developed. In another study, Mekheimer (2011) investigated the effect of exposure to supplementary video material on learners’ language development. Findings of the study demonstrated the important role of exposure to supplementary video material on whole language development. According to the study, authentic video is a valuable technique in language instruction. It can be implied from these findings that correct use of pedagogical films in classrooms assist learners to promote their learning and listening skills. The coordination of sounds and images can enhance the acquisition of learners. King (2002) asserted that the great value of films lies in its combination of sounds, images and sometimes text. Katchen (2003) further argued that DVD films can be employed as the major course material at university level to enhance the listening and speaking abilities of learners. His findings revealed that learners benefited from using DVD films. Generally speaking, creating a meaningful environment by the help of pedagogical films promotes the listening skills of learners and overcome limitations of a successful listening. The application of visuals, films, cartoons as instructional tools assist students to clarify the messages and augment understanding (Canning-Wilson, 2000). Moreover, this helps to strengthen the imaging systems which are an indispensable part of learners’ lives. The second research question of the study explored:Whether pedagogical films affect the listening skill of female and male learnersIn this respect, female and male learners’ listening scores were separated and analyzed for possible differences. The results of independent sample t-tests revealed that there are no statistical differences between female and male learners’ listening attainments. Findings denote that gender is not a contributing factor respecting the effect of pedagogical films. The two groups similarly made advantages from the movies worked during the class time. With respect to the literature, no other study unfortunately explored the effect of films regarding the impact of gender. All in all, Tuncay (2014) argued that films and moves particularly benefit both female and male’s language acquisition. He listed the chief effects of movies as the promotion of • critical thinking about the TL culture• understanding authentic language in various contexts• performative and receptive skills (speaking, listening)• fluency• writing as an integrated skill• use of TL for different functions and purposes• vocabulary and authentic expressions• appreciation of life in the TL country and the filming arts• the difference between the artificial use of TL in a non-native environment• interaction with peers in ELT class• the benefits of movies in acquiring the authentic aspect of the TL• the varieties of English demonstrated in the movies• language skills with fun and joy• translation skill from TL• grammar and structure (Tuncay, 2014, p. 59)According to these findings, it can be concluded that pedagogical films increase students’ curiosity and it can motivate them to follow the films. In this regard, Offner (1997) argued that learners become motivated by the help of watching film and this as a result leads to their language promotion. Accordingly, learners would actively participate in class discussion with low anxiety and apprehension (Bahrani & Soltani, 2002).

5.2. Conclusions

- Listening is an important skill in learning English as ESL/EFL. Language learners and teachers look for effective ways to increase this skill. Huge studies have done in this area and most of them have paid attention to provide a suitable condition for learners to enjoy learning (Goh, 2000; Vandergrift, 2005). On the other hand, multimedia breakthroughs have demonstrated and proved significant impact on learners’ learning processes. In this regard, the present study aimed at exploring the possible effect of the use of pedagogical films on listening skills of Iranian EFL learners. Learners in experimental watched the pedagogical films and worked on them, while control learners listened to CDs of the same films. Learners were also taken a pre- and post-test to further be checked the possible differences before and after the intervention. Data were collected and analyzed by the help of SPSS. Findings of the study revealed that experimental learners statistically took advantages in their listening improvement. The significant of differences between pre- and post-tests of experimental learners and post-test of experimental and control groups (p=0.00≤0.01) indicated that films are effective instructional means which enhance the learning process and promote the cognitive learning of language learners. The second objective of the study explored the possible differences between female and male learners in using pedagogical films. The results of independent sample t-test showed that there is no statistical significant difference between learners with regard to their gender. It denotes that movies motivate both female and male students, students may not feel bored with the environment, and there are friendly and positive atmospheres are in the classroom. This will end to greater concentration to learning, and upsurge learning much more than where students receive instruction through traditional approaches.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML