-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

p-ISSN: 2471-7401 e-ISSN: 2471-741X

2017; 3(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20170301.01

EFL Teachers’ Creativity and Their Cognition about Teaching Profession

Jahanbakhsh Nikoopour, Saeedeh Torabi

Islamic Azad University, Tehran North Branch, Iran

Correspondence to: Jahanbakhsh Nikoopour, Islamic Azad University, Tehran North Branch, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Creative teachers can provide opportunities for their students to develop to their greatest potential. The instructional decision and creativity that teachers use in their classes may be influenced by different cognitive and contextual factors. One of those cognitive factors which is hypothesized to be correlated with teacher’s creativity is their cognition or what they know, believe and think about teaching profession. The purpose of the study was to investigate the correlation between teachers’ creativity and their cognition about teaching profession among 135 male and female Iranian English language teachers who were teaching English in different Iranian state schools and private language institutes in two cities of Karaj and Tehran. Their age ranged from 20-48 years. They ranged from 2 to 28 years in terms of their teaching experience. All of the participants had university education in different English-language related fields. The participants were required to fill out two questionnaires of EFL Teachers’ Cognition and Creativity Questionnaire. Having collected the data, the researcher employed the Pearson-product moment correlation and detected a moderate but significant correlation between the EFL teachers’ creativity and their cognition about their teaching profession. Also, the results of an ANOVA showed that the EFL teachers’ years of teaching, age, gender and university degree made no significant difference in their creativity and cognition about their teaching profession.

Keywords: Teachers, Creativity, Cognition, Teaching Profession

Cite this paper: Jahanbakhsh Nikoopour, Saeedeh Torabi, EFL Teachers’ Creativity and Their Cognition about Teaching Profession, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20170301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Teacher CognitionFrom the 1960s onwards, there have been several studies which have reported the results about research on teacher cognition. According to Richards (2011), teacher cognition is now considered as an important component of current conceptualizations of second language teacher education including the mental lives of teachers, how these are formed, what they consist of, and how teachers’ beliefs, thoughts, and thinking processes shape their understanding of teaching and their classroom practices. Some researchers (Freeman, 1993; Richards, Ho & Giblin, 1996; Dunkin, 1995; 1996; Sendan & Roberts, 1998; and Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000) have indicated that teacher education has influenced teacher cognition about teaching profession.The importance of the study of teacher cognition goes back to over 30 years (Borg, 2006) where behavioristic view of language teaching with its primary emphasis on “effective teaching behaviors” (Borg, 2009, p.1) was the dominant teaching practice. This means that language teaching and learning theorists as well as practitioners were looking for teaching styles and strategies that were universally accepted as dominant and effective observable teaching practices. Borg (2009) calls this teaching practice a process-product model of research whose main goal was to “identify these effective behaviors in the belief that they could then be applied universally by teachers” (p. 11). Therefore, this implies that this line of research and practice did not pay attention to what each teacher in a particular teaching context knows, thinks and believes about teaching profession. Borg (2003) argues that with developments in cognitive psychology, research on teacher cognition and teachers’ mental lives was sped up and came to be established as a known and frequently studied area of teaching and learning in the 1980s. According to cognitive psychologists, there are complex relationships between what people do and what they know and believe. This line of research into teachers’ attitudes, identities and emotions provided us with rich knowledge about what teachers really know, think, believe and do when they teach in teaching contexts. In the 1990s, these teaching practices were critically criticized by cognitive psychologists who believed that teachers’ teaching practices are too complex to think of as effective observable teaching practices. This meant that teachers were considered as robots who had to do and implement or more particularly to teach in their classrooms what others define they should do. This reflects the idea that these teachers were not thinking about how they were teaching and they just continued teaching in the way designed and defined by others to teach (Borg, 2009). Cognitive psychologists argue that there are some other mental complex issues and various aspects of the psychological dimension of teaching that are likely to influence teachers’ everyday teaching practice. Additionally, Borg (2009) points out that the emphasis on the complex mental abilities of the teachers to teach has brought about the importance of the teacher’s mental and psychological dimension of teachers’ teaching practices or teachers’ cognition. Borg (2009) defines teacher cognition as “what teachers think, know and believe. Its primary concern, therefore, lies with the unobservable dimension of teaching-teachers’ mental lives” (p. 1). Elsewhere, Borg (2011) argues that teacher cognition is a broader term including “constructs such as attitudes, identities and emotions, in recognition of the fact that these are all aspects of the unobservable dimension of teaching” (p. 11).According to Kennedy (1991), these studies into not only what teachers do but also how they think have been reflected in different research projects. Moreover, Borg (2009) quotes some of these studies in the 1990s (Ball & McDiarmid, 1990; Calderhead, 1996; Carter & Doyle, 1996; Carter, 1990; Grossman, 1995; Richardson, 1996) and more recently (Munby, Russell & Martin, 2001; Verloop Van Driel, & Meijer, 2001). However, there are some figures in the field of teacher cognition who have been very influential and published a lot and have, in turn, made us aware of the significance of this totally previously neglected area of teaching facts. To give some examples, the work of Freeman and Richards (1996) is one of those early work into the filed which has brought to emphasize the importance of this area by investigating the mental and psychological dimensions of teachers’ work. Another work is the book written by Woods (1996), a book length study of teacher cognition. More recently, Borg (2009) has edited a book on teachers’ attitudes, identities and emotions, which is a rich collection of most contemporary works carried out in this filed. According to Phipps and Borg (2007), with the introduction of the concept of teacher cognition and what teachers know, think and believe, teaching profession was no longer thought and considered to be defined solely in terms of behaviors. Rather, they argue, teaching profession was viewed to be consisting of a set of thoughtful behaviors which teachers know and think about before they want to teach or while they teach. Drawing on Phipps and Borg (2007), Borg (2009) provides us with the nature of teacher cognition and its relationship to what teachers do.It is also important to note that some areas of language teaching and learning have received more importance compared to other areas. For example, Borg (2006) reviews studies that grammar teaching is the most researched area regarding teacher cognition. Therefore, this line of teacher cognition into teaching grammar has enriched out knowledge and understanding of the way teachers teach grammar and the way teachers think and react and reflect behind their practices. Also, the work of Andrews (2007) has investigated the kinds of knowledge teachers employ in teaching grammar and has brought to our attention the importance of what the teachers really know, think and believe about how and what they should teach. Andrews (2007) found that teachers’ own knowledge about grammar plays a significant role in the instructional decisions they make when teaching it, while Borg (2001), working with a teacher in Malta, showed that it was not only teachers’ actual knowledge of grammar that influenced their teaching, but also how confident they felt about this knowledge.Teaching ProfessionSome researchers (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Lave & Wenger, 1991; McLellan, 1996) showed that many teacher educators stress the point that situated cognition could improve career competence. Teaching profession demands teachers to possess detailed knowledge of subject content, age-specific pedagogy, and such skills as patience, leadership, and creativity. Additionally, Farrell and Oliveira (1995) sees teaching as an act which is logical and strategic. It implies interactions between the teacher and the students while they operate on some kind of verifiable facts and beliefs. Teaching and interaction within it motivate students to participate and express their own opinions. All in all, teaching is considered as a process which makes learning easier. More particularly, teaching is the specialized application of knowledge, skills and attributes which are designed to present unique service in order to meet the educational needs of the individual as well as society. The responsibility of the teaching profession is to choose learning activities by means of the aims of education. However, teaching profession is defined as “the teacher as an artist and teaching as an art” (Eisner, 1985). Wells (1982) further defines teaching profession as a series of such activities explaining, deducing, questioning, motivating, taking attendance, and keeping record of works, students’ progress and students’ background information which are done by teachers.Teacher CreativityAccording to Freeman (2002), teachers are now seen as active participants in language learning and teaching and successful teachers are considered to have significant impacts on learner’s learning performance. However, teacher’s success is not limited to the presence or otherwise to the absence of only one factor. Rather, various elements have been found to have influence on teacher’s success such as teachers’ personality and behaviors (Bhardwaj, 2009; Medley & Mitzel, 1955), teachers’ ability and skill (Porter & Brophy, 1988) and also environment and working conditions (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Korthagen, 2004). Among teachers’ ability and skills which are likely to have significant impacts on the way the teacher does his job in the classroom is his or her creativity. Torrance (1966, p. 6) defined creativity as "a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions, making guesses, or formulating hypotheses about the deficiencies: testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results."Dornyei (2005) believes that creativity is a concept that is absolutely familiar to both common people and professionals. He argues that creativity is associated with originality, discovery, divergent thinking, and flexible problem solving. According to Almeida, Prieto, Ferrando, Oliveira and Ferrandiz (2008), creativity is defined as “the skills and attitudes needed for generating ideas and products that are (a) relatively novel (b) high in quality; and (c) appropriate to the task at hand” (p. 54). According to Vygotsky’s (1978) cultural-historical theory of creativity, it is easy to understand that creativity is in nature collaborative and social. What this means is that creativity is socially co-constructed and, consequently, does not take place inside people’s head. Rather, as also argued by Csiksentmihalyi (1996), creativity does take place as a result of constant interaction of a person’s thought and the socio-cultural context. This means that creativity can rise in contexts in which a good connection is made between the person’s thoughts (or in broader terms one’s cognition) and the surrounding contextual factors. Such social contexts as schools and, in particular, the classroom within which students, teachers, peers and school officials as well as parents can interact prove as an advantageous context for developing teachers’ as well as students’ creativity (Cropley, 2009; Runco, 2004).This social approach to creativity is in sharp contrast with a cognitive perspective which views creativity as a personality trait (Whitelock, Faulkner, & Miell, 2008).Despite the fact that there is no agreement over the definition of creativity (Albert and Kormos, 2004) and different researchers in the field propose different conceptions of creativity, the issue appears to reflect certain personality or style factors. This implies that we should not neglect the effect and significance of personality traits on creativity such as an open mindedness, novelty, ambiguity tolerance. Moreover, we have to put into consideration the importance of such cognitive functions as ideational fluency and thinking flexibility when we consider the concept of creativity. Alencar and Fleith (2003) define creativity as “one of the main dimensions included in the majority definitions of creativity is the generation of a new product, idea, original invention, re-elaboration, improved products or ideas ” (p: 13). The search for such a link between teacher cognition and creativity is the rationale of the present study.

2. Purpose of the Study

- A lot of has been said about the important roles that teachers’ creativity and their cognition about teaching profession can play in teaching effectively and despite decades of research and theory on teachers’ creativity and their cognition about teaching, there is no or little (if any) research to investigate the relationship between these two teacher variables in Iranian EFL contexts. This gap provides enough impetus for the present research to explore the relationship of teachers’ creativity and their cognition about teaching profession. To this end, 135 male and female Iranian English language teachers in different Iranian state schools and private language institutes in two cities of Karaj and Tehran were asked to fill out EFL Teachers’ Cognition Questionnaire (Borg, 2003; 2006) and English Language Teaching Creativity Quotient (ELTCQ) Questionnaire developed by Albert P`Rayan. The results of the current study would, hopefully, enrich our understanding about the possible go-togetherness of teachers’ creativity and their cognition about teaching and provide pedagogical insights for future research to carry out such study in other similar EFL contexts.

3. Method

- Participants: The sample of the study included 135 male and female Iranian EFL teachers teaching English in different schools and private institutes in Karaj and Tehran. All participants were native speakers of Persian within the age range of 20 to 48. They were different in terms of their teaching experience. 26 participants were male (19%) and 109 were female (81%). All had university education in different branches of English i.e., English Teaching, English Translation and English Literature. Some were BA holders and others had MA degree in English. Instruments: two instruments were used in the study: 1. EFL Teachers’ Cognition Questionnaire about the language teacher education systems and teaching professions developed by Simon Borg (2003; 2006). It consists of 33 items constructed to assess the nature of language teacher cognition. It is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neutral”, “agree”, to “strongly agree”, and contained factual information such as age, gender, field of study, university degree, teaching experience, etc. Based on the added scores, those who scored higher than the “mean plus one” standard deviation possessed higher level of teacher cognition, those who scored lower than “mean minus one” standard deviation possessed lower level of teacher cognition, and those who scored within ‘mean plus and minus one’ standard deviation possessed moderate level of teacher cognition. 2. English Language Teaching Creativity Quotient (ELTCQ) Questionnaire developed by Albert P`Rayan which consists of 30 items in a 3-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree”, “agree to a certain extent” “disagree”. To obtain the level of the participants’ creativity, all the scores were added up for all 30 questions. A score of 120 – 150 suggests that the participant possesses a high potential level for creativity. Scores which were within 100 - 120 shows that the participant possesses above-average potential of creativity. A score of 75 – 100 shows average potential. Finally, a score that is below 75 suggests that the participant has a lower level of creativity.Procedure: Initial agreement was reached between the researcher and the dean of the institutes as well as the principals of the schools about the purpose of the study and data collection. The participants were given an orientation about the purpose of the study and their approval was obtained before the questionnaires were distributed among them. They were also made sure that their personal information and their responses to the questionnaire items would be kept quite confidential. Having explained the purpose of the study to the participants, the researcher distributed the two questionnaires to 150 EFL teachers. From among the received questionnaires, only 135 questionnaires were considered reasonable for analysis as the rest were not adequately answered. Then the correlation between the variables was computed.

4. Results

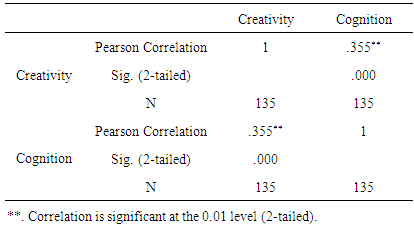

- The first step was to find the relationship between the EFL teachers’ creativity and their cognition about their teaching profession. To do so, the researcher attempted to use correlational analysis. Based on the Pearson correlation employed, the researcher detected a moderate but significant correlation between the EFL teachers’ creativity and their cognition about their teaching profession. As it is shown in Table 1, the correlation coefficient is 0.355, which is shown to be significant.

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The main variable under the study was teacher cognition; that is, what EFL teachers think, know, and believe and the relationships of these mental constructs to what teachers do in the language teaching classroom. Teacher cognition is a very complex construct which has been investigated in the general mainstream in three main themes: cognition and prior language learning experience; cognition and teacher education; and cognition and classroom practice. Understanding teacher cognition provides valuable insight into the mental lives of EFL teachers. It is ambiguous why there is no clear unity in the studies done so far on teacher cognition, and also, whether doing research in teacher cognition explores many important factors in language teaching which may influence teacher cognition or be influenced by it.The other variable under the study was teacher creativity. Creativity, which is considered as a vital twenty-first century skill, is seen as a very important variable in English language teaching. It is believed that creative teachers have positive impact on their learners and contribute to better learning. If EFL teachers can assess their own creativity, they will be motivated to take steps to enhance creativity in their career and become effective teachers.The primary aim of the present study was to find the relationship between teacher cognition and teacher creativity. The correlation between these two variables, though was statistically significant, was quite moderate. That is, the higher the cognition of EFL teachers, the more creative they are, and in turn, the more motivated they become, and the more achievement they get. The researcher utilized an ANOVA to compare the mean scores of the two groups; namely, female and male EFL teachers’ creativity scores. The results showed that the difference was not statistically significant. Also, the results of ANOVA showed that the difference between female and male EFL teachers’ cognition about their teaching profession was not statistically significant.

6. Discussion

- Putting it all together, it could be concluded that in teacher cognition and creativity, EFL teachers showed some positive correlation. However, their gender, age, teaching experience, and education level did not make a difference in their cognition and creativity.The study of language teacher cognition is beyond doubt a well-established domain of inquiry. Language teacher cognition research has understandably been heavily influenced by conceptualizations of teaching developed in other academic fields (e.g., Shulman’s notion of pedagogical content knowledge). This raises a key ontological issue regarding the extent to which language teachers, because of their subject matter, are similar or different to teachers of other subjects. The findings of this study highlighted that there is evidence to suggest that although professional preparation does shape trainees’ cognitions, programs which ignore trainee teachers’ prior beliefs and are innovative or creative in their own may be less effective at influencing these (Kettle & Sellars, 1996; Weinstein, 1990); and research has also shown that teacher cognition and creative practices are mutually informing, with contextual factors playing an important role in determining the extent to which teachers are able to implement instruction congruent with their cognitions (Beach, 1994; Tabachnick & Zeichner, 1986).The findings of the present study are in agreement with those of the previous ones (Richards, 2011; Yue & Yunzhang, 2011; Nishimuro & Borg; 2013; Damavandi & Roshdi, 2013). It should be mentioned that teacher cognition is now considered as an important component of current conceptualizations of second language teacher education including the mental lives of teachers (Richards, 2011); teacher cognition has a very important role in their classroom practice (Yue & Shi Yunzhang, 2011); and there is a relationship between EFL teachers’ practices and their underlying cognitions in teaching grammar (Nishimuro & Borg, 2013). It is also concluded that EFL teachers' beliefs about teaching grammar are affected by their prior language learning experiences, their teacher education courses, and their teaching experiences (Damavandi & Roshdi, 2013). The findings of the present study highlight the importance of the previous studies done on teacher cognition. Several studies such as Freeman, 1993; Richards, Ho & Giblin, 1996; Dunkin, 1995; 1996; Sendan and Roberts, 1998; Cabaroglu and Roberts, 2000) have indicated that teacher education has impacted on teacher cognition about teaching profession. In fact, EFL teachers’ language proficiency, pedagogical content knowledge, professional development, and their contextual knowledge are all important in shaping their cognition about teaching profession.It seems that the underlying principles of creativity is the end product of both cognitive and social issues which affect one another. This has found support in the literature when researchers in this filed come to conclusion that creativity in individuals is the combination of a set of cognitive, environmental, emotional, and motivational issues which interact in complex ways. Such cognitive factors as divergent thinking (Guilford, 1950, 1959), styles of thinking (Sternberg, 1997) and openness to experience (George & Zhou, 2001) have been introduced by psychologists to the field to account for the undeniable role and importance of these individual cognitive factors in developing creativity skills in people.The interrelationship of teacher cognition and creativity has been emphasized as the primary concern of the study, and based on the data analysis, it was proved that these two variables correlated positively. Due to the controversies among scholars on the creativity, which is considered as a social psychological variable by some, and a cognitive construct by some others, several studies have been done. Baer (1997, 1998), Hennessey (2000), and Zhou (1998) have done research on the influence of environmental factors involved in creativity from a social psychological perspective. Moreover, other lines of research have looked at creativity with relation to other factors which are likely to impact on creativity. For example, some studies (Forster, Friedman, & Liberman, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Markman, Lindberg, Kray, & Galinsky, 2007; Maddux & Galinsky, 2009) have brought to attention the importance of contextual factors and indicated that contextual factors influence creativity, creative thinking and problem solving. Accordingly, other studies (Feist, 1999; Simonton, 2000, 2003) have investigated the possible relationships between individuals’ personality traits and their creativity. The results of the present study confirm the complexity and multifaceted nature of teacher cognition and teacher creativity, which was tackled in previous studies. It was found that creative teachers are continuously asking questions, imaginative, and quick in answering to questions, highly active and possessing intellectual ability as what was found by Chan and Chan (1999). Teacher creativity affects the process of language teaching in many different ways: creative thinking and teacher effectiveness in higher education (Davidovitch & Milgram, 2006; Forrester & Hui, 2007), the effectiveness of using blogs in blended creative teaching (Lou, Tsai, Tseng & Shih, 2012), the correlation between teachers’ creativity and their success in classroom (Pishghadam, 2012). EFL teachers may have a key role to play in providing opportunities in classroom contexts for students to develop creativity. The naïve EFL teachers may understand creativity as breaking the rule, and doing the opposite; however, creativity is to be taught to EFL trainee teachers. As far as the importance of teaching creativity and training creative teachers are concerned, some studies agree with the concerns of the present study. Kampylis, Berki, and Saariluoma, (2009) set out to examine the importance and influence of creativity among in-service and pre-service Greek teachers in primary schools. Newton and Beverton (2012) aimed at examining pre-service teachers’ conceptions of creativity within the curriculum for English.

7. Pedagogical Implications

- The present study will have some pedagogical implications. An implication of such study is for the professional preparation and continuing development of language teachers. Teacher educators need to be and there is much evidence that they are considering the meaning of such bodies of research for the principles underlying the design of their programs; at a more detailed level, reflection is also required on how actual data such as case studies of teachers’ practices and cognitions from research might be made available to trainees and teachers as the basis of teacher education activities. Another implication of research in teacher cognition is that understandings of teacher cognition and practice developed in subjects such as mathematics and science can be carefully applied in the study of language teaching. This is an issue which needs to be investigated more carefully and explicitly in continuing work in the field. As Freeman (2002) claims, ‘when applied to language as subject matter, pedagogical content knowledge becomes a messy and unworkable concept’ (p.6). Andrew (2001) has also proposed ways in which general concepts such as subject matter knowledge might be related to those more specific to language teaching, such as teachers’ language awareness. Therefore, further exploration of such issues is required.One important implication of the present study is the role of context. Greater understandings of the contextual variables such as institutional, social, instructional, and physical factors which shape what language teachers do are central to deeper insights into relationships between cognition and practice. The study of cognition and practice without an awareness of the contexts in which these happen will inevitably provide partial or inaccurate characterizations of teachers and teaching. As there was a positive correlation between teacher cognition and creativity, it can have some implications for teacher educator programs. When teachers’ cognition about their subject matter (language proficiency for EFL teachers), pedagogical content knowledge, and contextual knowledge develop, they can, in fact enhance their professional development. Accordingly, they can show more creativity in their teaching activities in their classes. Therefore, the more their professional development, the more creative they will be in their career.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML