-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

2016; 2(1): 17-28

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20160201.03

Does First Language Attrition of Bilinguals Implicate Orthographic Skills in Native Ghanaian Akan Speakers? A Psycholinguistic Perspective

Stephen Ntim

Faculty of Education, Catholic University of Ghana, Sunyani, Ghana

Correspondence to: Stephen Ntim, Faculty of Education, Catholic University of Ghana, Sunyani, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Using statistical analysis of robust test of equality of means and Games-Howell test of comparison of mean scores, this study investigated the impact of L2 acquisition in L1 environment and how frequent use of L2 is likely to affect orthographic skills of persistent L2 users on L1 even within the same L1 setting. Using different linguistic instruments to measure participants’ linguistic proficiency in L1 orthography, findings show that L1 orthographic attrition within L1 setting is real. This attrition is interrelated in many ways not only with the acquisition of L2, but when L2 usage takes precedence of L1 in terms of frequency of orthographic use. Findings suggest a gain in one language becomes a cost to another, but not in terms of complete breakdown, even though the process appears to proceed slowly in L1 attrition that signs are often obscured. We interpreted the findings to corroborate with psycholinguistic models of the Activation Threshold Hypothesis and the Dynamic Model of Multilingualism.

Keywords: First language, Orthography, Attrition, Second language

Cite this paper: Stephen Ntim, Does First Language Attrition of Bilinguals Implicate Orthographic Skills in Native Ghanaian Akan Speakers? A Psycholinguistic Perspective, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2016, pp. 17-28. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20160201.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Research work in the acquisition of a second language often suggests the processes involved differ from that of native language acquisition (Bley-Vroman, 1990). The frequent assumption is that those factors influencing one’s ability to acquire a second language, such as, motivation, for example, is not likely to play any role in native-language development (Dornyei, 2001). This notwithstanding, other research evidence also indicate that knowledge of second language has influence on one’s ability to manage information in the native language (Marian & Spivey, 2003). Indeed, contemporary research work in both cognitive and psycholinguistics modelsof bilingualism makes the case that there is an interaction between one’s native and one’s second language in such processing as language-specific entities(Costa, Caramazza, & Sebastian-Galles, 2000; Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002; Ntim, 2016). Linguistic researchers continue to become more curious as to whether or not there exist some likely connection between phonological and orthographic representations in second language learners (Simon & Van Herreweghe, 2010). Indeed, copious research evidence suggest a link between the influence of phonology and orthography in second language (Georgiou, Parrila, & Papadopoulos, 2000; Basseti 2005; Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2008). For example, while orthographic skills are deemed to enhance learners performance in second language as far as word identification and phonology in the second language are concerned in some studies (Escudero & Wanrooij, 2010; Escudero, Hayes-Harb, & Mitterer, 2008), others fail to show positive relationship, suggesting rather that orthographic acquisition skills may be an obstruction with the acquiring new second language words (Hayes-Harb, Nicol, & Barker, 2010; Bassetti, 2006).Based on the above inconsistencies of research findings, this author in this study addresses the problem of linguistic attrition in bilingualism with specific reference to orthography skills in native/first language that has long been acknowledged in the literature, nevertheless, has not as yet received scientific studies from other geopolitical areas exposed to historical colonialism. In many countries in Africa, second languages, such as English, French and Portuguese among urban educated elites appear to be gradually taking over first/native languages, such that basic literacy skills as correct orthography and spelling in these native languages continue to become challenging especially for those exposed to many years of formal education and in highly placed areas as banking and finance, administrative positions, law firms, the academia, journalists, etc. in which these second languages continue to be the preferred official and national languages. Specifically, this research study focuses on language attrition in bilingualism, not exactly as understood in the sense of ‘subtractive’ bilingualism by Wallace Lambert, who was the first researcher to raise the problem with respect to both French Canadians and Canadians immigrant children whose acquisition of English in school precipitated the erosion of their native languages (Lambert, 1975, 1977, 1981). Nevertheless, linguistic ‘attrition’ as used in this research is akin to this same concept. While many studies have been conducted on the influence of phonological forms and orthography with respect to how orthography affects first language learners (Cutler, Treiman, & van Ooijen, 2010; Pattamadilok et al 2007; Tyler & Burnham, 2006), not much has been done on how second language acquisition influences orthographic skills in the native language. This is the position of researchers such as Simon and Van Herreweghe (2010). These authors maintain that whereas there is copious research work conducted on phonology and orthographic representations with first language (L1) acquisition, such as, Cutler, Treiman, and van Ooijen, (2010), Pattamadilok, Kolinsky, Ventura, Radeau, and Morais, (2007), not much work has been done to find out how over-use of second language (L2) consistently in L1 environment can influence phonology and orthographic skills f of first/native speakers who very rarely write in their native language (L1). Indeed, the influence of bilingualism to the point of second languages, such as English, French and Portuguese, almost eroding orthographic skills of first/native speakers among the urban educated elite in Africa has not been explored much. For example, research shows that knowing the spellings of words are more likely to enhance the memory of second language phonological forms. It is also on record that second language learners (L2) with Roman alphabets in their native/first language can remember with ease, newly-learned words. Can the reverse be the case? In other words, can second language learners’ (of English) who have been exposed for years in the English language, due to many years of formal education (with the native/first language being on the attrition) be aided or impeded in the orthographic processes in the native language? Few if any scientific studies have been conducted on this topic in many countries in Africa where almost ‘subtractive’ bilingualism undermine effective orthography of native/first languages. It is also established in linguistic literature that knowing a second language can potentially help manage information in native language (Marian & Spivey, 2003) and indeed recent models of bilingualism that are cognitive and psycholinguistic based makes the assertion that two languages interact even during language-specific processing. Nevertheless, the extent to which second language is capable of influencing native language functions has not received the much needed scientific research. This research is meant to fill this gap. Based on the above problem, the following four (4) research questions guided this paper:1) Do highly proficient L2 language (English) users in Ghana likely to manifest signs of L1 (Akan) attrition? 2) Can overlap in orthographic systems in Akan and English help to mediate accurate Akan spelling for Ghanaian bilingual users?3) Can Akan speakers of English use their knowledge of the alphabetic principle to infer phonological forms of new words in Akan and write them accurately? 4) What is the extent of L1 (Akan) attrition/maintenance amongst the group of adult Ghanaian bilinguals investigated?It is on record that not more than four percent (4%) of the languages around the globe have received recognized status in countries in which these languages are spoken. This reflects the reality of the problem in the global linguistic market. This is especially the case, when indigenous languages become and continue to become subsumed under second languages, such that after a considerable number of years in formal education, in civil, economic, educational and political administration, and other official work, which require the usage of second language (as this is the case in Africa), many young people exposed to extensive years of L2 can hardly write accurately their own native language, even though they may be able to speak it appreciably well. This situation may not be as dire as it is in Ghana, since there is a clear language policy at the level of basic education. Nevertheless, the persistent seeming weak linkages between policies and planning is likely to render many language policies in Africa ineffective. Over the years, international organizations as well as agencies continue to recommend the use of languages of minority groups especially in education. However, these initiatives lack legal power to enforce them. Additionally, policies as such, have very little impact if any, especially when it comes to home use of first/native language which is the basis for enhancing the continued transmission of such languages. When home use of second language is preferred to native language, no amount of legal backing can help maintain first/native languages. This appears to be the emerging trend in many literate urban African communities for the last four-five decades. These communities are more likely to speak English, French or Portuguese (the three main official languages in many countries of Africa) even in the homes with their children. Besides, educational institutions have the responsibility not only to maintain, but also to enhance minority languages and their cultures. Consequently, the arguments of those who advocate for English-only, guided by the view that the school has the responsibility to prepare children to function in a dominant society are no longer tenable. The school as a social institution, is also required as part of its fundamental social function, to support not only heritage cultures of the children it serves, but also the fact that school retention and academic success of children is also directly linked to their firm grasp of native language (Ntim, 2016). Based on the above, the findings of this paper will be of significant benefit to all educational stakeholders, especially language teachers, linguists, psycholinguists, educational psychologists, curriculum designers, parents, etc. to understand the extent of the interplay of first language attrition, and how this has impact on native Akan orthographic skills of those exposed to second language usage for many years. The findings of this research study will also serve as a resource in language education policy in Ghana and other parts of Africa and will contribute to the literature on language and bilingualism.

2. Literature Review /Theoretical Framework

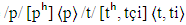

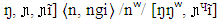

- Link between Phoneme and OrthographyResearch in psycholinguistic study consistently indicates a link between word recognition and orthography. Just as word recognition is influenced by orthography, so also the latter significantly enhances phonemic awareness (Tyler & Burnham, 2006; Perre & Ziegler, 2008; Cheung, Chen, Lai, Wong, & Hills, 2001; Tyler & Burnham, 2006). Notwithstanding, this correlation between the two, not much studies have been conducted specifically, on how orthographic skills in first/native language is likely to be influenced exert as a result of second language acquisition. Indeed, with respect to the influence of word identification in subtractive bilingualism on orthography, few studies if any have been conducted. Specifically in psycholinguistics studies, previous research studies focused on two issues namely, the effects of inconsistencies of spelling-to-sound and sound-to-spelling inconsistencies with respect to word recognition (Ziegler, Petrova, & Ferrand, 2008; Pattamadilok, Morais, Ventura, & Kolinsky, 2007; Ziegler & Ferrand, 1998. The goal of these studies is to get some insight into how accurately graphemes are mapped on to phonemes when literate people are linguistically engaged in reading and writing as well as finding out whether or not there is any feedback between the three components of lexical, phonological and orthographical. For example in the studies conducted by Goswami, Ziegler and Richardson (2005), findings suggest that the beginning of reading has significant effect on the child’s ability to develop phonological system.The question of how reading and writing in second language are likely to have predicting influences on first language writing systems have been recently discussed amply by researchers such as Cook and Basseti (2005), Weber and Cutler (2004) and Escuredo, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer (2008). For example, Weber and Cutler (2004) make the submission that knowledge in first language orthography is likely to have some influence of second language word processing. Evidence for this was demonstrated in the research conducted by Escuredo, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer (2008) that orthographic input during training on new words has some influence on listeners’ word-recognition pattern. Processes of Linguistic Attrition and Acquisition Research findings on language attrition studied from diverse perspectives remain inconclusive and contradictory. In the literature on linguistic attrition, two main groups of population have been studied namely, child bilinguals and adult bilinguals. Conclusions on the latter generally appear to be imprecise ranging from such conclusions as ‘surprisingly little loss’ (de Bot & Clyne, 1989), ‘despite self-perceptions of significant first language decline’ (Schoenmakers-Klein Gunnewiek 1998; de Bo & Clyne 1994; Jaspaert & Kroon 1992; Jaspaert & Kroon 1989; de Bot; Jordens, de Bot et al. 1989) to some report on some aspects Olshtain and Barzilay 1991; Major 1992; Ammerlaan 1996; Waas 1996; Kopke & Nespoulous 2001; Schmid 2001; Pavlenko 2003).In the case of the former, bilinguals for most of the time have to abandon their first/native language for exclusive second language usage when found in a different environment, such as a native Ghanaian Akan speaking child having to forego completely Akan in favour of English when he/she finds herself/himself in the UK, USA, Canada, Australia or New Zealand (cf. Magiste 1979; Leyen 1984; Kaufman 1991; Schmitt 2000). A special case of child adoptees in the literature have been identified to lose completely any trace of their native/first language is also reported in the literature for more than a decade (Pallier, Dehaene et al. 2003; Ventureyra, Pallier et al. 2004). The other population is second language speakers who for frequent use second language have a tendency to lose their first/native language (Hansen 1999). Thus, since the last 1980’s and the beginning of this millennium, findings of research study on language attrition do not generally corroborate. This is because there is still some doubt as to whether or not children or adults who have acquired a certain level of proficiency of native language can indeed be exposed to significant attrition, and if so how, and what might be the plausible psycholinguistic explanation (Kopke & Schmid 2004: 1). In an attempt to find some answers to this question, there are as many opinions in the literature, as there are researchers in the field. For example, Seliger (1991:227) makes the submission that, first language attrition is an ‘ubiquitous phenomenon found wherever there is bilingualism’ while this same author further in Seliger (1996:616 cited by Herdina & Jessner, 2005:95) opines: "In cases other than language pathology, we do not expect an established L1 to deteriorate or diverge from the grammar that has been fully acquired". (Sharwood, 1983:229). This author perceives language attrition as ‘an all-pervasive problem not restricted to a very limited number of sociocultural scenarios’ (ibid). These varied conclusions are consequent upon methodology used in these studies. Current research however now sees language attrition as starting or constituting essentially a processing phenomenon such that the perception of ‘no loss’ is likely to be true only at the knowledge level (Hulsen 2000; Sharwood & van Buren 1991). What these current findings imply is that first/native language attrition is a rare phenomenon especially for adults because they attain maximum competency in their native language. Nevertheless, psycholinguistic evidence is also increasing that language whether first or second is impervious to complete loss. They are likely to fade as a result of non-use, even though they are still kept in the human memory architecture, but with frequency of non-use, first or second languageis susceptible to becoming less and less accessible almost to the point of being loss (deBot & Hulsen 2002: 253). Linguistic attrition then, especially of first/native language, is not as categorical a phenomenon as one of degree. Evidence from the literature suggests that in comparison with child attrition, adult first language attrition is relatively low. This evidence in the literature has some scientific support that corroborate such psycholinguistic view as the ‘immutable proficiency’ perspective as well as the ‘threshold of frequency of use’ proficiency level which constitutes the cut-off level for language to become immune to loss (de Bot 1998: 351). Pan and Berko-Gleason (1986:204 cited also in de Bot and Hulsen 2002: 260) also makes reference to a ‘critical mass of language that, once acquired, makes loss unlikely’. In the case of second language attrition, most research evidence suggests high proficiency rate as well as age as good predictors for linguistic retention (Herdina & Jessner 2002: de Bot & Hulsen 2002:259); This leads us to consider two theoretical models of language attrition and retention: a) the dynamic model of multilingualism and b) the activation threshold hypothesis.Models of Language Attrition and AcquisitionThe Dynamic Model of Multilingualism In broadest outline, the dynamic model of multilingualism makes the assumption that neither language acquisition nor language attrition can be fully understood when discussed in isolation. The two processes of acquisition and attrition need to be seen as integrated part of a dynamic system that keeps revolving. In simple terms, language attrition is a function of language acquisition (Jessner 2003: 242). The fundamental constructs in this psycholinguistic model can be summarized in the following processes: input; memory constraints; resource limitations; competition; activation/inhibition in neural networks; retrievability; controlled vs. automatic processes; and the declarative/procedural knowledge continuum. In this framework first/native language is defined to be as "both a decline of retrievability of declarative linguistic knowledge and deproceduralization of linguistic knowledge in L1, and an increase of competition by L2 knowledge" (de Bot 2002). The fundamental point of this definition is that second language (L2) has a role to precipitate first/native language attrition. This is especially so in neuro-and psycholinguistic terms. Activation Threshold Hypothesis and Subset HypothesisThe Activation Threshold Hypothesis (ATH) as perceived by Paradis (2001:12 and Paradi, 1993:139) can be summed up in the following two psycholinguistic perspectives: a) a model for accounting for receny, frequent effects and priming phenomena as well as language attrition and b) as a framework for accounting for dissociations between comprehension and production in first and second language acquisition, language attrition and amnestic aphasia. This activation threshold hypothesis is an aspect of the Integrated Neurolinguistic Theory of Bilingualism together with the Three-Store and Subset Hypothesis of Paradis (2001). This threshold hypothesis relates basically to two variables, namely, a) the retrieval of items stored in memory and b) the frequency of usage and re-inforcement within the context of activation/inhibition framework. This is how Kopke and Schmid (2004: 23) put it: ‘Activation and inhibition mechanisms allow to account for the control of multiple languages in the brain […] as well as for changing dominance patterns’.The Subset hypothesis also makes the case that varied languages are stored separately in neural networks which simultaneously form part of one linguistic system. These networks made up of linguistic items of a given language are connected by memory traces of different strengths and quantity forming nodes. When learning L2, items are connected with the corresponding items in the native/first language (L1) but gradually when L2 continues to grow, the correspondences begins to separate out leading to intraliguistic connections becoming sharper, stronger and more numerous than the interlingistic connections. The obvious implication here is this: t the underlying difference between intra and interlinguistic connections becomes more of quantity rather than qualitative (cf. Herwig 2001: 118). Consequently, growth in linguistic proficiency likely to precipitate first language attrition is more a quantitative increase in the strength and the number of intralinguistc connections, which can also lead to automated processing. So whereas the Subset Hypothesis focus on input memory storage processes as described above, the Activation Threshold rather has to do with retrieving what has been stored from memory and Paradis sums it up as ‘an item is activated when a sufficient amount of positive impulses have reached it. The amount necessary to activate the item constitutes its activation threshold. Every time the item is activated, its threshold is lowered and fewer impulses are required to reactivate it.’ (Paradis 2001: 11). Different types of processing require different activation level. For example, language comprehension compared to language reconstruction will require fewer amounts of positive impulses. Reconstruction would rather require fewer impulses than production (self-activation). This means that for both comprehension and reconstruction, a higher activation threshold is tolerable, since an item available for comprehension may also need a high activation threshold for production. However, with passage of time, an item activation threshold used not too long ago, gradually also comes to the fore implying that items frequently used tend to have lower activation thresholds, since they are available for processing than those used less frequently. Activated items which have not been used for a longer period become more cumbersome to activate (retrieve) for processing. This framework discussed holds for both monolingual and multilingual situations. This has implications for linguistic attrition: there appears to be two different sources for first language (L1) attrition: a) the possibility of increased use of another language and b) direct interactions with second language (L2) as a result of increased and proficiency in second language (L2). In sum then first/native language attrition is likely to be predicted due to frequent lack of stimulation which Paradis calls "the result of long-term lack of stimulation"(Paradis 2001: 11f) and Kopke and Schmid also describe ‘as a natural consequence of lack of use" (Kopke and Schmid (2004: 23). With this as backdrop, we discuss below, the nature and origins of Akan orthography highlighting the nuances of its grammar which when unused orthographically for a long time can trigger attrition for even for the native speaker. Origins and Nature of Akan Orthography Orthographic antecedent or the ‘correct writing’ of Ghanaian languages goes back to over one hundred years. Well known sources precipitating the codification of Ghanaian languages, especially Akan with its variety of dialects into alphabetic symbols, could be traced back to Christian missionaries around the 17th and 18th centuries, such as the Danes, Germans and British. They were initially written mainly in religious publications for Christian religious instructions and education. Additionally, the publication of Lepsius’s ‘Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages and Foreign Graphic Systems to a Uniform Orthography in European Letters’ in the latter half of the 19th century in 1855 and 1863 also popularized interest in committing unwritten African and Ghanaian languages into symbolic alphabetic codification. There are currently three standardized orthographies for Asante, Akuapem and Fante. The British colonial government especially during the time of Governor Guggisberg in the then Gold Coast (modern Ghana) encouraged the use of native language as early as lower primary school. There is also a unified Akan orthography created during the 1980s. This quest for committing Ghanaian languages into writing was re-invigorated in the latter part of the last century with the establishment of the Akan Orthography Committee in 1978, revised by the Bureau of Ghana languages in 1995 and launched in 1997. The Akan language in Ghana is homogenous to about seven million people in Central and Southern Ghana, La Cote d’Ivoire, and central Togo, all in West Africa. In Ghana, there are numerous dialects of Akan and it includes Asante Twi, Fante, Bono, Wasa, Nzema, Baule and Anyi, with a high level of mutual intelligibility between them. Akan as a language is part of the linguistic tradition that linguists refer to as the Kwa branch of the Niger-Congo languages. Ghanaian linguistic researchers classify the homogeneity of Akan language into two clusters: a) cluster 1 is referred to as the r-Akan. This cluster does not explicitly have the letter ‘l’ in in their original proper use. This cluster 1 of Akan includes: Asante, Akuapim, Mfantse, Abron (Bono), Wassa, Asen, Akwamu, and Kwahu. The second cluster is called the l-Akan and comprises Nzema, Baoule, Anyin and other dialects spoken mainly in the Ivory Coast, whose use of the letter “r” in proper usage is very rare. These two clusters are generally referred to as the ‘Tano Language Group’ because native speakers span from the Volta river in Togo and Ghana to the Tano river Basin in Ghana and La Cote D’Ivoire. Akan (Asante) Phonology, Consonants, Vowels, Advanced Tongue Root (ATR) Harmony, Tone Terracing and Verbs For the purpose of this study, we will confine the major orthographic nature of Akan to the Asante language since phonology, consonants, vowels and advanced tongue root (ATR) harmony in every language is directly linked to its orthography and the former differs a bit from the various dialects. Besides, it is the variant of Akan that this researcher is a native speaker and more comfortable with. Asante also referred to as ‘Asante Twi’, like all Akan dialects, in terms of phonology involves the following three characterizations: a) extensive palatalisation, b) vowel harmony, and c) tone terracing. With respect to consonants, Asante Twi consonants before front vowels are palatalized (or labio-palatalized), and the plosives are to some extent affricated. The allophones of /n/ tend to quite complex. Some palatalized allophones that have more than minor phonetic palatalization in the form of the vowel /i/ also do occur. These sounds do occur before other vowels, such as /a/, even though, they may not be that common. In Asante Twi,

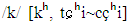

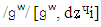

is followed by a vowel it is pronounced

is followed by a vowel it is pronounced  whereas in in Akuapem it remains

whereas in in Akuapem it remains  The sequence

The sequence  is pronounced

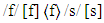

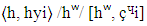

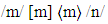

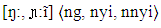

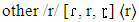

is pronounced  The subsequent are in the order /phonemic/, [phonetic],

The subsequent are in the order /phonemic/, [phonetic],  Note that orthographic

Note that orthographic  is ambiguous; in textbooks,

is ambiguous; in textbooks,  may be identified from from /dw/ with a diacritic:

may be identified from from /dw/ with a diacritic:  Likewise, velar

Likewise, velar  may be transcribed

may be transcribed  Orthographic

Orthographic  is palatalized

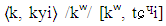

is palatalized  labial alveolar dorsal labialized voiceless plosive

labial alveolar dorsal labialized voiceless plosive

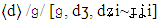

voiced plosive

voiced plosive

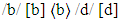

fricative

fricative

nasal stop

nasal stop

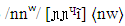

geminate nasal /nn/

geminate nasal /nn/

Certain words in Asante such as demonstrative pronouns ‘yei’ (this) are written with the ‘y’, but when pronounced it is, ‘Wei’. In terms of phonemic tones, Asante Twi has three phonemic tones, high (/H/), mid (/M/), and low (/L/). Initial syllable may only be high or low. Tone terracing is also critical in Asante. The phonetic pitch of the three tones is environmental-dependent. Most frequently, it is lowered after other tones, producing a constant decline which linguistic experts calls ‘tone terracing’. For example, /H/ tones have the same pitch as a preceding /H/ or /M/ tone within the same tonic phrase, whereas /M/ tones have a lower pitch. That is, the sequences /HH/ and /MH/ have a level pitch, whereas the sequences /HM/ and /MM/ have a falling pitch. /H/ is lowered (downstepped) after a /L/. /L/ is the default tone, which emerges in situations such as reduplicated prefixes. It is always at bottom of the speaker's pitch range, except in the sequence /HLH/, in which case it is raised in pitch, but the final /H/ is still lowered. Thus /HMH/ and /HLH/ are pronounced with distinct but very similar pitches. Verbs are always combined orthographically with personal pronouns in Asante, and never separated. For example in the present continuous in English which is written as: ‘I am going’ (which is separated in English) in Asante it written together as:

Certain words in Asante such as demonstrative pronouns ‘yei’ (this) are written with the ‘y’, but when pronounced it is, ‘Wei’. In terms of phonemic tones, Asante Twi has three phonemic tones, high (/H/), mid (/M/), and low (/L/). Initial syllable may only be high or low. Tone terracing is also critical in Asante. The phonetic pitch of the three tones is environmental-dependent. Most frequently, it is lowered after other tones, producing a constant decline which linguistic experts calls ‘tone terracing’. For example, /H/ tones have the same pitch as a preceding /H/ or /M/ tone within the same tonic phrase, whereas /M/ tones have a lower pitch. That is, the sequences /HH/ and /MH/ have a level pitch, whereas the sequences /HM/ and /MM/ have a falling pitch. /H/ is lowered (downstepped) after a /L/. /L/ is the default tone, which emerges in situations such as reduplicated prefixes. It is always at bottom of the speaker's pitch range, except in the sequence /HLH/, in which case it is raised in pitch, but the final /H/ is still lowered. Thus /HMH/ and /HLH/ are pronounced with distinct but very similar pitches. Verbs are always combined orthographically with personal pronouns in Asante, and never separated. For example in the present continuous in English which is written as: ‘I am going’ (which is separated in English) in Asante it written together as:  and never

and never

represents the personal pronoun, “I” and

represents the personal pronoun, “I” and  the continuous tense. This perhaps has to do with the fact that Asante language is more verbal and active oriented than passive. These constitute some grammatical nuances complicating Asante Twi orthography. For example, whereas Mfantsi will say: ‘Merekɔnnasie’ (‘I am going for thanksgiving’, also written with the verb and the personal pronoun together), the typical Asante will rather make it more active, such as

the continuous tense. This perhaps has to do with the fact that Asante language is more verbal and active oriented than passive. These constitute some grammatical nuances complicating Asante Twi orthography. For example, whereas Mfantsi will say: ‘Merekɔnnasie’ (‘I am going for thanksgiving’, also written with the verb and the personal pronoun together), the typical Asante will rather make it more active, such as  (‘I am going to give thanks’). These two variants of Akan have the same meaning, but one can see that the Asante rendering is more verbal and active. For text translations to make any meaning to the Ashanti, the translator need not be oblivious of such linguistic-specific nuances of the Asante language. Current StudyThe purpose of this current study is not simply linguistic as psycholinguistic. It is to investigate the link between phonology and orthography within the context of bilingualism and first/native language attrition and the psychological implications that underscore why native Akan speakers after many years of exposure to dominant second language (English) fail to write accurately their native Akan. If there is anything that comes to the fore from the theoretical/literature review above, it is the fact that phonology is closely related to orthography. Psycholinguistic research evidence copiously suggests that word recognition is influenced by orthography, just as the latter also significantly enhances phonemic awareness. Given this backdrop, how do we explain the seeming phenomenon of first/native language ‘attrition’, when many literate native speakers of Akan in Ghana are able to speak it eloquently, in addition to an appreciable level of intelligibility and even speak (as among many educated Ghanaians) impeccable English (second language), but are less likely to write accurate Akan? What are the possible psycholinguistic/psychological explanations for this, given the fact that psychologically, native speakers hardly forget their native/first language? Is it the nature of the phonological complexity such as a) extensive palatalisation, b) vowel harmony, and c) tone terracing, the palatalized (or labio-palatalized), and the affricated plosives that make it difficult for literate native speakers to write better Akan (Asante Twi)? The fundamental hypothesis being tested in this current study is this: highly proficient second language (l2) users in Ghana are likely to show signs of first language (L1) orthographic attrition.

(‘I am going to give thanks’). These two variants of Akan have the same meaning, but one can see that the Asante rendering is more verbal and active. For text translations to make any meaning to the Ashanti, the translator need not be oblivious of such linguistic-specific nuances of the Asante language. Current StudyThe purpose of this current study is not simply linguistic as psycholinguistic. It is to investigate the link between phonology and orthography within the context of bilingualism and first/native language attrition and the psychological implications that underscore why native Akan speakers after many years of exposure to dominant second language (English) fail to write accurately their native Akan. If there is anything that comes to the fore from the theoretical/literature review above, it is the fact that phonology is closely related to orthography. Psycholinguistic research evidence copiously suggests that word recognition is influenced by orthography, just as the latter also significantly enhances phonemic awareness. Given this backdrop, how do we explain the seeming phenomenon of first/native language ‘attrition’, when many literate native speakers of Akan in Ghana are able to speak it eloquently, in addition to an appreciable level of intelligibility and even speak (as among many educated Ghanaians) impeccable English (second language), but are less likely to write accurate Akan? What are the possible psycholinguistic/psychological explanations for this, given the fact that psychologically, native speakers hardly forget their native/first language? Is it the nature of the phonological complexity such as a) extensive palatalisation, b) vowel harmony, and c) tone terracing, the palatalized (or labio-palatalized), and the affricated plosives that make it difficult for literate native speakers to write better Akan (Asante Twi)? The fundamental hypothesis being tested in this current study is this: highly proficient second language (l2) users in Ghana are likely to show signs of first language (L1) orthographic attrition.3. Research Methodology

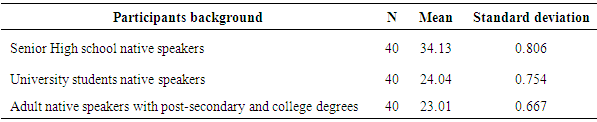

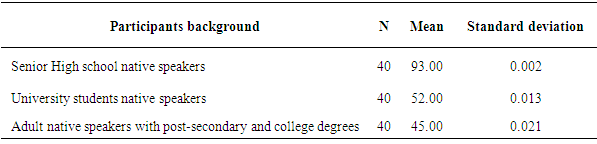

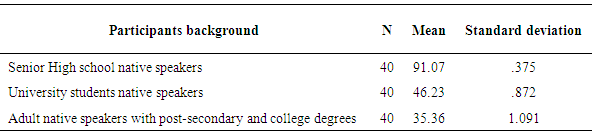

- Sample and DesignThis study used the purposive, random stratified sampling design from an estimated one hundred and twenty (120) young and adult Ghanaians. All one hundred and twenty (120) participants were biliguals who were both native speakers of Akan (Asante Twi) with Asante Twi as their first/native language (L1) and English as their second language (l2). This was the sampling procedure: forty (40) were drawn from four (4) Senior High Schools students whose area of academic specialization was not language, from two out of the ten (10) administrative regions of Ghana; another forty adult students (40) were also selected from four (4) universities spread across the country; twenty (20) adult workers who were university graduates and were working in various administrative positions, such as banking and finance, journalism, law firms, academic institutions, etc. were also sampled from Ghana and another twenty (20) adult Ghanaians who have stayed in the United States of America (New York city) for over 30 years also volunteered to participate in this research in the summer of 2016. An estimated 50% were females. On a 4-point scale (1 =no high school diploma to 4 = college degree), the average level of maternal education of these participants was 2.2 (SD = 1.1). The age level of participants ranged from 15-55 years, while their exposure to English as second language for 33% of them ranged from 9-49 years, the remaining 67% of them, the exposure tallied with the age range. In other words, for majority of these participants, they had been bilingual since infancy. Thirty-three percent (33%) of these participants had university degrees, ranging from basic bachelor’s to second degree Masters and PhD holders, while the other 67% were in their various academic areas of formation in the universities and the Senior High Schools. All the one hundred and twenty (120) participants did not take Ghanaian language as a course of studies either in the Senior High Schools or in the Universities, apart from the mandatory course in Ghanaian language (Akan) as a course of study at the basic level of Education in the primary and Junior High School as required by the Ghana Education Service. Procedures and Measures Using variants of the Modern Linguistic Aptitude Test byAbrahamsson and Hyltenstam 2008; Abrahamsson, N. and K. Hyltenstam (2009) and Altenberg, E. P. (1991), with all instructions and measures in Asante Twi, participants orthographic skills in Asante Twi were tested in the following: a) film retelling and transcription; b) picture naming task description; and c) sentence generation tasks in three (3) different experiments. The purpose of these experimental tests was to measure the four research questions that guided this research study.Experiment 1: Film Retelling and Transcription This first experiment tested the selected one hundred and twenty (120) on the correspondence between phonology and orthography by means of asking them to retell and transcribe what they have heard and seen a film. They were scored according to errors made along the following three main measures: inaccurate spelling, poor grammar; lack of meaning. All raw scores were computed into means and standard deviations. The subsequent was the film which they were to transcribe (translate) into Asante: […] C(harlie) C(haplin) is released from prison with a letter recommending him as an honest and trustworthy man. He takes this letter to a shipyard […], is accepted for work there but messes up rather badly and leaves. He walks through the city where he meets a young girl who's just stolen a loaf of bread. She is apprehended by the police, but he tries to claim it was him. However, a bystander says it was her, so he is released again. He goes into a restaurant, eats a lot of things and then says he can't pay, so he is arrested again. After a bit more to-ing and fro-ing, he's loaded into a police van, into which the girl is then also put. During an accident they manage to escape, and then walk through the suburbs. They sit in front of a house, and CC starts fantasizing how nice it would be for them to live in a house like that. They wake up back to reality and realize they're very hungry, and there is apoliceman standing behind them. They get up and walk away, […]. (Schmid 2004: 13)Results

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

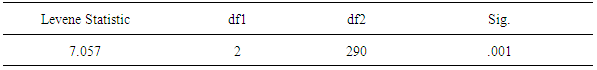

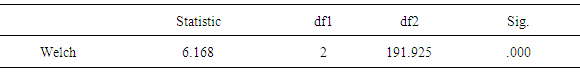

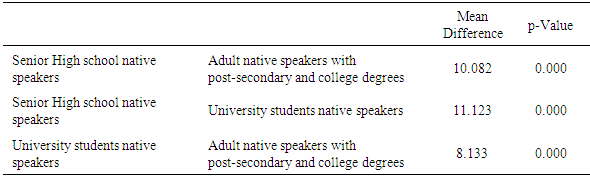

- The findings from the three experiments conducted above can be summed up as follows from the data above: a) first language orthographic attrition is real especially among those who frequently use second language as medium of communication for a very long time; b) first language attrition generally but more specifically orthographic skills is not a solitary psycholinguistic phenomenon; it is interrelated to both second language acquisition and frequency of its usage; c) first language attrition proceeds very gradually. It precedes actual deterioration of linguistic proficiency; d) the process appears to be directly linked psycholinguistically to the Activation Threshold Hypothesis and The Dynamic Model of Multilingualism.Speaking from the cognitive perspective of the information processing theory, psychologically, there is nothing like absolute forgetfulness. This is especially so with respect to native/first language. All information that is processed and is stored in the Long Term Memory (LTM) is there permanently and cannot be eradicated. It is the same with language acquisition generally whether first, second or third language. This notwithstanding, after long usage, decay sets in so that when it comes to retrieving the information from the LTM, it becomes difficult. It is not the information as such that is lost permanently, but the rather the retrieving cues helping the person to retrieve the information. It is within the context of such information-processing psychological perspective that first language attrition can be seen to be real. As indicated in all the findings from the experiments, the data suggest that much younger people seem to score better than older people. Our data contradict that of many research studies on attrition. In almost all the literature on attrition, notwithstanding the contradictions, the emerging picture seems to be that for adults the level of attrition is rather low compared to much younger people (cf. Kopke & Schmid 2004: 10). This is because such studies were rather more interested in the environmental variable where native speakers outside of their own linguistic environment tend to lose their native language for the prevailing language such as a Ghanaian-born child in the US will lose Akan for English faster than the parents. Our study was the other way round. Both native adults and native younger speakers were tested in their own native environment on orthographic skills and the age variable presented a rather different picture: younger people less exposed to second language compared to adults performed better on orthographic skills- an indication of the length of the decay effect.What this means in effect is that, first language attrition appears to be linked with the process of second language acquisition as well its frequency of usage even within the same environment as indicated in our findings. This suggests \ language attrition is generally is interconnected with other variables such as length of acquisition, depth of learning, extent of language use and its production. It is not a solitary process. Intuitively then, it appears to be that a gain in one language becomes a cost to another, but not in terms of complete breakdown, or loss but rather a longstanding loss precipitated by “disuse, lack of input or reduced input” (Bardovi-Harlig & D. Stringer 2010:34) In short, our findings corroborate the fact that first language attrition is a reality even though the process appears to proceed slowly such that consistent signs are often obscured. These findings contradict the myth in the language literature that L1 proficiency once acquired is immutable as underscored in the regression hypothesis of Jakobson (1945) which posits that languages acquired earlier are impervious to loss or The idea of the ‘native perfect speaker’ is no longer tenable from the psycholinguistic perspective.Additionally, the problem of native language attrition with respect to healthy individuals seems to manifest itself in generational gaps as suggested in the above findings: a) first generation population L1 language attrition to L2 due to extensive usage; b) second-generation who inherit this native language along with the second language (English) gradually also begin to ‘lose’ the native language just like the first generation after long exposure to second language due to formal education and so on as corroborated in this study. Much younger adults in the Senior High schools are relatively better when it comes to recalling correct orthographic skills, (for example, which sentences are grammatically correct to be written together or separated especially when a verb is joined to personal pronouns or possessive pronouns as in Asante Twi ), just as those in the universities performed better than the third group. This confirms previous research (Jessner 2003; Meara 2004) that emphasized that those aspects of language acquired earlier are likely to be exposed to increased variability or ‘scatter’ triggering deterioration in proficiency as in shown in the orthographic skills of adult bilingual Ghanaians compared to much younger ones.The findings again are consistent with the psycholinguistic model of the ‘Activation Threshold Hypothesis’ (ATH) of Paradis and the ‘Dynamic Model Multilingualism’ (DMM) proposed by Jessner. The core thesis of the Activation Threshold Hypothesis as mentioned in the literature above is this: there are three underlying cognitive factors of the ATH: a) memory retrieval and b) the frequency of use and c) all of which are implicated by activation/inhibition. The processes of activation and inhibition allow for both multiple languages in the brain, as well as any changes regarding dominance patterns. Precisely because languages are stored separately in neural networks, and these are connected by different linguistic memory, with traces of different strengths, the more they are activated, the more the more they become active. The learning of the items of a second language (L2) has correspondence with those of L1. So when L2 continues to grow (as in the case of adult Ghanaian professionals who use English more frequently even in the same Ghanaian environment), the correspondences between L1 (Asante Twi) and L2 (English) begin to separate out, triggering intralinguistic connections becoming sharper and more numerous than interlinguistc connections. In this respect, as indicated among the three groups of participants in this study, the longer the period of usage and frequency of L2 (English), the more L2 (English) become active in the memory traces inhibiting that of the first language Akan (Asante Twi). From the psycholinguistic perspective then, the relatively poor performance of older people in relation to the younger people in orthographic skills could possibly be explained by activation/inhibition processes. So the challenges in orthographic skills exhibited by much older people as per the findings of this paper appear to be due to insufficiently low activation threshold and this confirms the position of Kopke and Schmid (2004: 23). This finding is also in line with recent study in English language attrition through computer aided education by Yu, (2013) in which this author compared the Regression and Threshold Hypotheses in English language attrition and found the latter to support language attrition.The findings also corroborate the ‘Dynamic Model Multilingualism DMM’ proposed by Jessner (2003). Within this theoretical framework which is more neurological in approach, second language (L2) acquisition and frequency of exposure is more likely to trigger first/native language attrition. The psycholinguistic reasons are these: a) there is an increase of competition by L2 knowledge; b) there are memory constraints due to resource limitations in the human memory architecture; c) therefore the activation/inhibition in neural networks becomes activated in favour of L2 (when used profusely and frequently as opposed to L1) and d) this has effect on retrievability when it comes to controlled versus automatic processing. In effect then, the language used often and frequently (L2 English) as in the case of adult speakers) becomes automatic and procedural as against controlled and declarative continuum of first language (Asante Twi orthography which is very rarely used by adult native speakers) orthography tested in this study. It is in this respect that the findings in this study confirms the position of de Bot (2002) that profuse use of L2 is likely to induce both a decline of retrievability of declarative as a deproceduralization knowledge of L1, while increasing activation competition in L2. Thus, the findings above suggest that frequent use of L2 (English) even in native environment, where writing of the first language (L1) is very rarely used, basic literacy skills such as orthography in the first (L1) is likely to be implicated by the second language (L2) causing first language (L1) attrition due to insufficiently low activation threshold in L1 as well as the activation/inhibition in neural networks in L2 becoming activated in favour of L2 as opposed to that of L1.So the underlying idea being suggested by the findings of this research is that language maintenance and especially orthographic skills are predicted by language contact. Whether in the Activation Threshold Hypothesis (ATH) or Dynamic Model Multilingualism (DMM), contact and of course by implication, frequency of use are the primary factors precipitating or inhibiting language attrition. For the ATH, when language is not used (and in this study L1 orthography is very rarely used), the activation threshold, and its items within it, are likely to rise to obstruct access. So the frequent use of L2 orthography for participants who have used it for many years inhibited L1 orthographic skills. Similarly, within the DMM, insufficient maintenance effort is the primary predictor for language attrition because, when efforts are expended acquiring and using the orthography of another language (L2), the L1 user will arrive at a psychological critical point and limits in which the support of L1 wanes through continued use. Therefore, the data as presented in this study seem to support the argument in bilingualism that single-factor analysis cannot adequately explain language attrition. This is especially so when there are many factors such as explained above. However, contrary to the view of the on-going debate in the literature that adult bilinguals compared to younger ones are less susceptible to language attrition, our findings rather suggest otherwise. In fact , with respect to L1 orthographic attrition in the same socio-cultural environment (L1 setting), in which L1 orthography is very rarely used as in this study, younger people seems to be better when it comes to testing basic literacy orthographic skills than adults largely due to the differences in years of usage of L2.

5. Limitations of This Study

- The findings of this study are only preliminary. We acknowledge that it was designed to assess particular constructs of participants’ proficiency in orthographic skills in L1 within the same L1 socio-cultural environment. Consequently, the findings are likely to be constrained by the method used, and so they cannot be said to be exhaustive. This is especially so when the study also lacked the cross-cultural linguistic perspective. This notwithstanding, the findings still give some indications of the reality of first language (L1) attrition in basic literacy skill as orthography among some group of population whose use of the second language (L2) overrides the first language. Further study may be needed with the cross-cultural perspectives.

6. Conclusions

- This study investigated the impact of L2 acquisition in L1 environment and how frequent and persistent use of L2 is likely to affect orthographic skills of persistent L2 users in L1 even within the same L1 setting. Using different linguistic instruments to measure participants’ linguistic proficiency in L1 orthography through statistical analysis, we were able to show that L1 attrition within L1 setting is real. This attrition is also interrelated in many ways not only with the acquisition of L2, but essentially when L2 usage takes precedence of L1 in terms of frequency of orthographic use. The findings suggest some corroboration with psycholinguistic models of the Activation Threshold Hypothesis as well as the Dynamic Model of Multilingualism. The Activation Hypothesis posit the thesis that when L2 usage continues to grow and connections become sharper and more numerous, there is a triggering effect and L1 slowly begin to decay. Similarly the Dynamic Model of Multilingualism is predicted to trigger increased variability likely to precede actual deterioration as far as proficiency is concerned. These psycholinguistic findings have some implications for language policy in Ghana which keeps fluctuating since the time of British colonial rule. They underscore the importance of ensuring that native/first languages continue to become part of basic education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML