-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

2016; 2(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20160201.01

The Effect of Listening to Comic Strip Stories on Incidental Vocabulary Learning among Iranian EFL Learners

1Department of English, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

2Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The effect of listening to comic strip stories on incidental vocabulary learning is the aim of this study. To this end, two groups including twenty pre-intermediate students as an experimental group and twenty students as a control group were participated. A vocabulary knowledge scale (VKS) was given to all participants as a pre-test and post-test to measure learners’ knowledge rest on 18 unknown target vocabularies. An experimental group listened to comic strip stories with watching photos of stories, whereas the control group just listened to comic strip stories without watching any photos of stories. The results showed that both groups had a significant improvement after treatment, and listening to stories had an effect on vocabulary learning. In addition, to compare both groups’ performance on post-test, an independent t-test was administered which indicated that there was a significant difference between experimental group and control group whilst, experimental group learners almost performed better than control group learners which conveys watching stories’ comic photos can affect on incidental vocabulary learning remarkably.

Keywords: Incidental vocabulary learning, Comic strip stories, Vocabulary knowledge scale, Listening

Cite this paper: Omid Arast, Bahman Gorjian, The Effect of Listening to Comic Strip Stories on Incidental Vocabulary Learning among Iranian EFL Learners, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20160201.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Vocabulary learning is an essential part of language learning (Yoshii, 2002). There are many definitions of vocabulary learning importance in other researches, and the vocabulary learning enthusiasts revealed the vocabulary significance in their researches. As Shoebottom (2014) ascertains the more words you know, the more you will be able to understand what you hear and read, and the better you will be able to say what you want to when speaking or writing. Words are the currency of communication; speakers will not be able to communicate with each other without words (Alexander, 2014). Ahmad (2011) in his study quotes that vocabulary learning is an indispensable process for ESL learners to acquire proficiency and competence in target language. Having studied vocabulary learning instructions, many techniques are revealed. Finocchiaro and Bonomo (1973) conveyed many techniques for teaching vocabulary; they talked about that we give our students an understanding of the meaning in many ways: we dramatize; we illustrate using ourselves and our students; we show pictures or objects; we paraphrase; we give the equivalent if necessary; we use any appropriate techniques. In the other hand, Claudia Pesce (2012) in her article describes five best ways to instruct new words to learners: show students illustrations, flashcards, posters, synonyms and antonyms, setting a scene or situation and the substitute it with a new word or phrase, miming and total physical response (TPR) which many teachers believe learners who learn best by moving their bodies, actions and imperative mood and the last one is the realia (real-life objects in the ESL classroom) which can help to present new words.Many scholars in their studies divide the vocabulary learning into two instructional techniques: incidental learning and intentional learning. Many definitions about these techniques are given by many scholars although Yali (2010) points out the incidental learning is defined as the type of learning that is a by-product of doing or learning something else; whereas, intentional learning is defined as being designed, planned for, or intended by teacher or students. He describes that incidental learning defines the approach of learning vocabulary through texts, working on tasks or doing other activities that are not directly related to vocabulary, whereas the intentional learning always focuses on vocabulary itself, and combines with all kinds of conscious vocabulary learning strategies and means of memorizing words. As stated in Krashen (2013), a large portion of second language (L2) vocabulary knowledge is acquired incidentally in the sense that words are acquired as a natural by-product of children/learners performing everyday linguistics activities and tasks. Incidental learning is the process of learning something without the intention of doing so; It is also learning one thing while intending to learn another (van Zeeland, 2013; Ahmad, 2011).To acquire vocabulary in incidental mood, many kinds of methods are introduced. Listening, as another way of incidental vocabulary acquisition is the process of receiving, constructing meaning from, and responding to spoken and/or nonverbal messages” (Brownell, 2002). Listening is important for effective communication because 50 percent or more of the time we spend communicating is spent listening. The optimal goal of L2 listening development is to allow for the L2 to be acquired through listening. Vocabulary is precisely one of the language components that can be acquired through training in listening skills (Montero Perez & Desmet, 2012).Nowadays, there is a tendency toward using media to aid and supplement educational objectives. At real life English, it is believed that language learning should be fun so the better way to enjoy learning the English language through comic strips. The most frequently mentioned asset of comics as an educational tool is its ability to motivate students. A comic strip is defined as a sequence of drawings arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, and usually arranged horizontally, with text in balloons and captions (Liu, 2004; Haines, 2012; Merc, 2013). Based on Liu (2004), a comic strip is described as a series of pictures inside boxes that tell a story. Among visual genres, comic strips catch many researchers’ attention because they are communicative, popular, accessible, and readable; Comic strips communicate using two major media—words and images—a somewhat arbitrary separation because comic strips’ expressive potential lies in skillfully employing words and images together.Comics can teach children to infer meaning from the visual first. Comics must include pictures; you can even tell a story without words. The benefits of using comics in the classroom in agreement with Hanies (2012) are certainly great, both in increasing literacy and in addressing the educational needs of differentiated learners, so the teacher chooses and uses world with particular care to keep the students and the other space for growth in vocabulary and language development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Using Comic Strip Books to Teach English Vocabulary

- The use of graphic novels in language classrooms has a short history; therefore its literature is rather limited. Although there are not many comprehensive studies assessing their impact as teaching tools, the feedback from educators and scholars as to the use of graphic novels in language classrooms is a clear indication of their worth as a pedagogical tool (Yildirim, 2013). Comic Book Classroom was founded in Denver, Colorado in 2010. Comic Book Classroom is a standard-based curriculum that examines and explores age-appropriate comic literature with the intent of furthering literacy and introducing students to book culture in the larger scope. As Baker (2011) defines graphic novels are a subset of the comic genre. Both terms will be used in this research. Comics and graphic novels both use graphics and text to tell a story. In addition, the goal is to teach students not just reading and art skills, but engage them in discussions about the texts that may help them tackle problems in their own lives and communities. The use of comics in education is based on the concept of creating engagement and motivation for students.Wright (2001) claims the effectiveness of comics as medium for effective learning and development has been the subject of debate since the origin modern comic book in the 1930s.The use of comics in education would later attract the attention of Fredric Wertham who noted that the use of comics in education represented "an all-time low in American science. The use of cartoons in your teaching has several advantages: they give life to classrooms, they promote students engagement, they improve students’ learning, they prolong student’s attention span, and they also enhance student’s communicative and linguistic competences.Liu (2004) in his article talked about the role of comic strips on ESL learners’ reading comprehension .He has two different students’ levels of proficiency (low & high) with and without a comic strip. This study suggests that the reading comprehension of the low-level students was greatly facilitated when the comic strip repeated the information presented in the text. He noted that the effect of comic strips on reading comprehension largely depends on the quality of the repetition effect. The study’s results also imply that the advantage of providing comic strips with reading text diminishes when the student has difficulty comprehending the text. After analyzing the results, it was said that low-level students receiving the high-level text with the comic strip scored significantly higher than their counterparts receiving the high-level text only. Lang (2009) evaluates comic strip has very consequential role in the English classroom, he defines comics are the most widely read media throughout the world – especially in Japan. As he describes problem of language teachers: constantly searching for new innovative and motivating authentic material to enhance learning in the formal classroom. A textbook is made of material that has been altered and simplified for the learner. He notes some characteristics that make comics thus attractive as an educational tool: a built-in desire to learn through comics, easy accessibility in daily newspapers, ingenious way in which this authentic medium depicts real-life language, people and society and eventually variety of visual and linguistic elements and codes that appeal to students with different learning styles. Furthermore, he suggests comics can be used: a) to practice describing characters using adjectives (e.g., Garfield is a very troublesome cat), b) to learn synonyms and antonyms to expand vocabulary, c) to practice writing direct speech (e.g., 'Hey, move your car!') and reported speech (The man told him to move his car.), d) to practice formation of different verb tenses(i.e., changing the present tense of the action in the strip to the past tense), e) to practice telling the story of a sequentially ordered comic strip that has been scrambled up and finally, f) to reinforce the use of time-sequence transition words to maintain the unity of a paragraph or story (e.g., First, the boy left for school. Next, he . . .).Based on Bowkett’s (2011) book, he uses children’s interest in pictures, comics and graphic novels as a way of developing their creative writing abilities, reading skills. The book’s strategy is the use of comic art images as a visual analogue to help children generate, organize and refine their ideas when writing and talking about text. In reading comic books children are engaging with highly complex and structured narrative forms. Whether they realize it or not, their emergent visual literacy promotes thinking skills and develops wider Meta-cognitive abilities. Baker (2011) tried to examine the benefits of using comics with English language learners (ELLs). With their bright colors and familiar characters, comics are more appealing than traditional text. The comic represents something different and exciting without sacrificing plot, vocabulary, and other important components of reading comprehension. For these reason and many more, comics might also play an important role in ELL acquisition of literacy. She expresses many graphic novels are high interest with low reading levels, cover diverse genes such as biographies, and cover current events and social issues. Baker (2011) concurs with comics can be used to teach parts of speech, social situations, historical events, and more. She admits that incorporating text and visuals causes readers to examine the relationship between the two and encourages deep thinking and critical thinking.According to Bowen (2011), comic strips can be very motivating for learners as the story-line is reinforced by the visual element, which can make them easier to understand. He designed many activities for teaching vocabularies through using comic strips in class: for example he used the comic strip stories in one activity that is cutting up the strip into individual boxes and getting the students to rearrange them into an appropriate order. Another activity is to blank out alternate boxes, so Khoiriyah (2011) in his thesis used comic stories to improve the students’ level of vocabulary. He believes the students identify and study words from the context on the comic reading. Story from comic offers a whole imaginary world, created by language which students can learn and enjoy; this story is designed to entertain. Khoiriyah (2011) endeavors to find out whether there is a significant difference in vocabulary score of student taught using comic stories and those taught using non-comic stories or not. The instrument to collect the data were; observation and test. Observation was only used to support the data about students’ imagination on reflected on their engagement in learning processes. The researcher gave two times teaching to both classes, after the treatment the researcher analyzed the obtained data and concluded that the performance of experimental group that used the comic stories for learning vocabulary is better than the control group.Karakas and Sariçoban (2012) in their study, considered the impact of subtitled animated cartoons on incidental vocabulary learning, and found out that the target words were contextualized and it became easy for participants to elicit the meanings of the words. For the aim of this study the researchers selected 42 first grade teaching students in Turkey. To collect data from the subjects, a 5-point vocabulary knowledge scale was used and 18 target words were integrated into the scale. After subjects had been randomly assigned into two groups (one subtitle group and the other no-subtitle group), they were given the same pre- and post-tests. The general findings of this study supported the common assumption that subtitles and captions are powerful instructional tools in learning vocabulary and improving reading and listening comprehension skills of language learners.Merc (2013) considered the effects of comic strips on reading comprehension of Turkish EFL learners. In his study, students read the texts given and wrote what they remembered about the text on a separate answer sheet. The results of the quantitative analyses show that all students with a comic strip effect, regardless of proficiency and text level, performed better than the ones without the comic strips. Yildirim (2013) in his research applies graphic novels in classroom as a teaching tool and provides the necessary background information, the historical evolution of graphic novels. He confesses that in language classrooms graphic novels can be used to boost many different skills. The researcher talks about the historical overview of using the graphic novels in different cultures and compares its use in various literatures around the world.Cimermanova (2014) believes the role of graphic novels in foreign language teaching, too. Using pictures, storytelling, and creative writing are the activities used more or less regularly in foreign language teaching. She admits that in language teaching picture books present an authentic material. Her article discussed the possibilities of using picture books in language teaching and presents the qualitative case study results focused on effectiveness of using wordless picture books. Cimermanova (2014) conveys reading graphic novels brings authentic material to the EFL class and encourages students’ critical thinking. She agrees that the use of picture books contributed to a recognition that it is important to “read” the illustrations that may influence our perception, that details are important for understanding the complexity of the whole.

2.2. Statement of the Problem

- To learn vocabulary incidentally, the learners may encounter many obstacles and restriction or problems, all researchers that studied these issues proposed to work out these problems. They used many techniques to learn vocabulary through four skills, this study tries to focus the listening techniques for learning vocabulary (the receptive learning) and as you read many articles, there are many ways for learning incidental vocabulary. As Mousavi and Gholami (2014) state new methods of English language teaching should use new materials to draw learners' attention for acquisition of English language. To put it another way, nowadays there is a tendency toward using media to aid and supplement educational objectives. This study used the listening to comic strip books and their funny pictures and checked the role of listening skill on incidental vocabulary acquisition. After studying the many researches, we understood that many researchers studied large issues about incidental vocabulary learning through many ways, the present study attempts to examine the effect of incidental vocabulary learning on listening through comic strip stories which it is an attractive technique to learn vocabulary. To investigate the role of listening to comic strip books on incidental vocabulary learning, the research question aimed to discover whether listening to the comic strip books affect the incidental vocabulary learning.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

- The participants of this study were 40 pre-intermediate level EFL learners from Rahyan-Danesh Institute of Ahvaz. All of them are female and the range of their age was between 10 to 16 years old. They were selected based on non-random judgment sampling from 86 students at private language institute through their performance on proficiency test designed based on Interchange Placement Test (Lesly, Hansen & Zukowski, 2005). For running this study the participants were randomly pigeonholed into two groups, 20 students as experimental group (Group A), and 20 students as control group (Group B). The participants shared the same linguistic and background knowledge and they were unaware of the purpose of study as vocabulary acquisition.

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. Comic Strip Book

- The researcher for teaching the incidental vocabulary through listening have selected the seven comic strip stories from The Brain comic strip series books (Bang , 1957),which retrieved from the website named www.comicbookplus.com . This comic story book has big hero whose nickname is Brain with several interesting adventures. The words which used in this series books are so simple which are adequate to pre-intermediate readers absolutely.

3.2.2. Research Tests

- The Interchange Placement Test (Lesly, Hansen & Zukowski, 2005), which includes 70 items (20 listening items, 20 reading items and 30 language use items) was used to determine participants’ proficiency level. According to Kuder-Richardson (KR-21) formula, the reliability of the proficiency test was estimated to be (r=.905). In order to choose target words, fifty words from the comic strip stories were selected and placed in vocabulary knowledge scale (VKS) (Wesche & Paribakht, 1996). This test was piloted with 10 learners at pre-intermediate level and those words which learners know their meaning was deleted because the aim of this study is to show that learners incidentally acquired the words which they have not already known them. Finally, the eighteen unknown target words were chosen for the current study based on the results of pilot group.The researcher has applied the same pre-test and post-test for both experimental and control groups, based on the unknown selected words. This test is five-point self-reported scale of vocabulary knowledge scale (VKS) (Wesche & Paribakht, 1996) was adopted to measure the vocabulary development of the learners before the treatment and after the fulfillment of treatment. This scale which was applied by some scholars (e.g., Rieder, 2003; Mahdavy, 2011; Karakas & Sariçoban, 2012; Mousavi & Gholami, 2014) in previous studies should focus on evaluating the taught target vocabularies or idioms during the treatment. It composed of 5 levels as follows and this scale is scored according the following table (scores apply to each individual target words):1: I don't remember having seen this word before. (0 point)2: I have seen this word before but I don't know what it means. (1 point)3: I have seen this word before and I think it means ________ (synonym or translation). (2 points)4: I know this word. It means __________ (synonym or translation). (3 points)5: I can use this word in a sentence. e.g.: ___________________ (if you do this section, pleaseAlso do section 4). (4 points)The reliability coefficient of the pretest and post-test were (r=.976 & r=.947) respectively, which estimated by using Kuder-Richardson (KR-21) formula.

3.3. Procedure

- The study has lasted for 21 days, 3 sessions a week during the period of one semester (3 weeks, 9 sessions). The teacher chose seven simple stories from The Brain series books. He selected just last 30 minutes of each session. The researcher gave proficiency test to all participants for determining their levels in first session .In second session the participants were taken the pre-test VKS and their data were calculated .This treatment has begun from third session to eighth session in third week. In the treatment sessions, the teacher has provided slides for each short story before each session. Both groups listened to the same stories which were included same vocabularies but in different mediums. For experimental group, researcher provided the power point slides for each story to teach it audio-visually. He has explained the stories by providing them with some more expressions or comic pictures in order to draw their attention to the target vocabularies. This group listened to the teacher who told the story by help of showing the pictures of comic stories on the scope of video projector in front of the classroom. Afterwards, for control group, he utilized his voice which recorded in experimental group sessions formerly. He explained all of the stories in this group without showing any slides to them. The control group has just listened to the recorded voice of teacher who retelling the story, without observing the slides of pictures of comic strip books on video projector. They had to visualize the story in their mind and just listened to the voice of the teacher. The post-test was administered in ninth session in third week of semester after passing the 6 sessions of treatment. The questions of post-test were similar to pre-test (VKS). The post-test was given to both groups on similar condition and time for answering them.

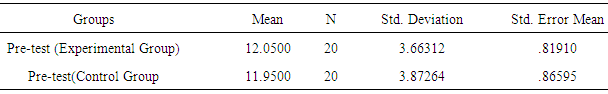

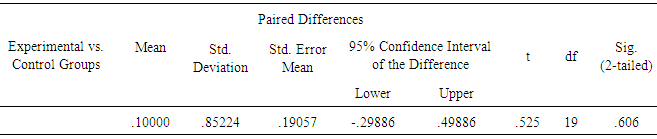

4. Results

- The statistical calculations and results of the study obtained from analyzing the learners’ performance on Interchange Placement Test as homogeneity test and also vocabulary knowledge scale (VKS) as pre-test and post-test are presented. Next, the analysis went further to find out if there is any difference between both groups ( groups A & B) on pre-test and post-test. The analysis on the pre-test was conducted to find any significant differences between two groups’ performance on the pre-test through the Independent Samples t-test in Table 1.

|

|

|

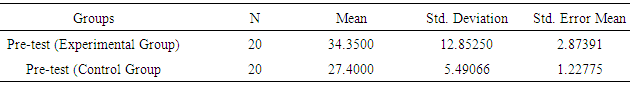

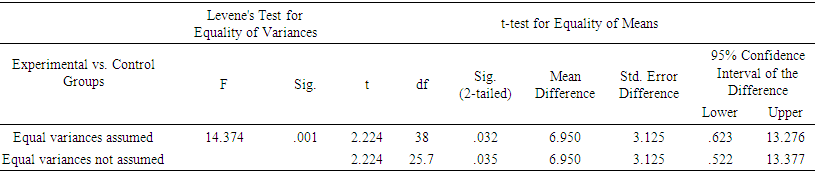

| Table 4. Independent Samples t- Test on the Pre-test of the Groups' (Post-test) |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- Findings of the study suggest that the mean scores of pre-test of both groups were very close to each other. It is assumed from this finding that both groups had similar knowledge about the target words before they were exposed to the treatment. The development in each group was measured through t-test which demonstrated that there was an improvement in each group and also the scores of all participants in two groups on post-test had been progressed. It is clear that high differences in mean score of each group show that both groups after passing the treatment accompanied by using listening to comic strip stories have promoted on post-test scores. Results indicated the differences in mean scores in both groups were significant, (p < 0.05). Regarding the comparison of mean differences in groups A and B, it might be concluded that there were significant differences between two groups while progress in group A is slightly more than group B. Thus, it might be concluded that what facilitated the improvement in vocabulary knowledge was listening to comic strip stories while using comic pictures can have more impact on acquiring incidental vocabulary in relation to only listening to these stories. It is concluded that listening to comic strip stories can affect on incidental vocabulary learning. However, by comparing the results of two groups by using independent t-test, the difference between two groups was significant, so the experimental group which used watching pictures of the stories could perform better than other group. The present study confirms the findings of Lang’s (2009) study, who evaluates comic strip has very consequential role in the English classroom, he defines comics are the most widely read media throughout the world. Lang (2009) describes problem of language teachers: constantly searching for new innovative and motivating authentic material to enhance learning in the formal classroom. A textbook is made of material that has been altered and simplified for the learner. He agreed by using comic books, the learners can learn different kinds of topics in classroom. Like this current study, Liu (2004) in his article talked about the role of comic strips on ESL learners’ reading comprehension .He has two different students’ levels of proficiency (low & high) with and without a comic strip. The outcome of the present study is compatible with Bowkett’s (2011) book, which in his book the author uses children’s interest in pictures, comics and graphic novels as a way of developing their creative writing abilities, reading skills. The book’s strategy is the use of comic art images as a visual analogue to help children generate, organize and refine their ideas when writing and talking about text. He agrees in reading comic books children are engaging with highly complex and structured narrative forms.Bowen (2011) describes that comic strips can be very motivating for learners as the story-line is reinforced by the visual element, which can make them easier to understand. There are a number of different ways to use comic strips. He designed many activities for teaching vocabularies through using comic strips in class: for example he used the comic strip stories in one activity that is cutting up the strip into individual boxes and getting the students to rearrange them into an appropriate order. In another study, Khoiriyah (2011) uses comic stories to improve the students’ level of vocabulary. He suggests the students identify and study words from the context on the comic reading. His findings infer that the performance of experimental group that used the comic stories for learning vocabulary is better than the control group.Karakas and Sariçoban (2012) in their study, considered the impact of subtitled animated cartoons on incidental vocabulary learning, and found out that the target words were contextualized and it became easy for participants to elicit the meanings of the words. Their results were in related to the current study which the general findings of this study supported the common assumption that subtitles and captions are powerful instructional tools in learning vocabulary and improving reading and listening comprehension skills of language learners. Moreover, Merc (2013) considered the effects of comic strips on reading comprehension of Turkish EFL learners. In his study students read the texts given and wrote what they remembered about the text on a separate answer sheet. The results of the quantitative analyses show that all students with a comic strip effect, regardless of proficiency and text level, performed better than the ones without the comic strips.

5.2. Conclusions

- The present study aimed at investigating the effect of listening to comic strip stories on incidental vocabulary learning of a pre-intermediate Iranian EFL learners group. This study showed Iranian EFL learners picking up the meaning of unfamiliar words encountered incidentally in task materials as they listened to comic strip books. The results of the study showed that listening to comic strip stories had statistically meaningful effect on the performance of language learners on acquiring incidental vocabulary. Findings from the study show that after treatment both experimental group and control group have improved in their results on post-test. In addition, independent sample t-test between two groups indicates that the results of experimental group in comparison of the results of control group were better and their performance was more excellent too. As a whole, it seems that listening instruction affected the L2 learners’ performance on the incidental vocabulary learning. It can be concluded from the findings of the current study that comic pictures of such strip books can influence on better vocabulary acquisition. Furthermore, the low acquisition rate of word meaning found here, as well as in other incidental learning studies, emphasizes once more the importance of combining incidental learning with some sort of explicit focus. Subsequently, the findings of this study reveal that incidental vocabulary acquisition in listening modes by using various methods can indeed occur and that comic strip story might be an effective tool to support vocabulary learning. The findings of this study also present that vocabulary development is a long lasting process that needs to be supported by contextual clues. Finally, as the research interest of this study, comic strip use had a significant effect on students’ recall of both pre-intermediate EFL learner groups who used the listening method to acquire the new words. This study found that comic strip use noticeably facilitated the listening comprehension of students at pre-intermediate level. Once again, it was proved that students be provided texts with a visual material, the comic strips in particular, in their reading comprehension and listening classrooms.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML